The millionaire who created a real-life toy train set on a human scale

The astonishing assemblage of buildings, machinery and memorabilia at Fawley Hill, Buckinghamshire — the home of Lady McAlpine and the late Sir William McAlpine — is testimony to one man’s remarkable enthusiasm for the railways, as Marcus Binney discovers. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

The landscape park at Fawley Hill is like no other. Begun as a hobby, it has grown into a work of art with the classic elements of an aristocratic park, including roaming deer, rolling greensward, eyecatchers and follies. The difference is that its creator, the Hon Sir William ‘Bill’ McAlpine, who died in 2018, was inspired not by a vision of Arcadian antiquity, but the Railway Age. His celebration of the railways is on a scale that only the scion of a major construction company could ever have brought together. Country Life once called it ‘bonkers’, but Bill’s understanding of the workings of railways was the match of any Georgian Earl or Marquess’s knowledge of ancient Rome or Athens.

Fawley Hill has a strong element of the funfair, but it is based no less on connoisseurship, scrupulous research and an insatiable and impetuous passion for collecting. Of course, trains are not to everyone’s taste. As an Italian visitor to Fawley observed — perhaps ironically — ‘lovely park, pity it is so close to the railway’, as he watched a steam engine disturbing the peace of the Thames Valley with loud chuffing, hoots and plumes of vapour.

Bill was first and always an engineer at heart. Although born in London’s Dorchester Hotel (which Sir Robert McAlpine Ltd built and owned) he was never happier than when surrounded by engine drivers and steam buffs. The annual Vintage Transport Weekends at Fawley included steam traction engines heaved across the Shires, all brightly coloured and polished in their liveries, as well as every other form of transport, even if the boats had to be on trailers.

The park at Fawley Hill is also an animal sanctuary and seven types of deer are kept here, including African marsh deer (Sitatunga), sika, axis, and Père David with their velvety antlers. These were not only for ornament, nor even the table. Rather, Bill formed a link with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) when he built the railway at Whipsnade in Bedfordshire and served on the Council of ZSL for many years. He offered homes to animals they and other zoos couldn’t house, provided they posed no threat to current incumbents or neighbouring humans.

More recently, he worked with Tiggywinkles, an animal-rescue hospital that gives free treatment to injured wildlife, with the animals either released back into the countryside or popped through the gates of Fawley Hill. As a consequence, the park today hosts 24 species of animals, including five types of antelope, emus, various camelids, goats, pigs, wallabies, three types of lemur and meerkats offering rare interest to the turning circle in front of the house. The last tapirs and capybaras died of great old age and Lady McAlpine is hoping someone might soon be looking for homes for what were clearly some of her favourites.

The house built by Bill and his first wife, Jill, will be described next week. His father offered him a site on the family estate near Henley north of the Thames and construction of the Fawley Hill Railway began in 1965, with only 100 yards of track, a set of points and two sidings. Other railway buffs, whether children or adults, settle for model railways or narrow gauge (and at country houses such as at Exbury, Hampshire, and Gwrych Castle, Conwy, the latter are major attractions). For Bill, it had to be the real thing: the standard gauge of British Rail with authentic locomotives and rolling stock. This presented colossal challenges in transporting trains and rolling stock to a new line not connected with any other (or likely to be).

The contours of the land and the gradient of the eventual track (the steepest standard gauge in the world) limited the length of the engines and carriages he could use. Pride of place goes to a true Thomas the Tank Engine, delivered to McAlpine’s from Hunslet in Leeds in 1913. This was an 0-6-0 Saddle Tank, No 31, the first locomotive to arrive at Fawley. It came by road from the McAlpine depot at Hayes. An attempt was made to tow the trailer across the fields to the new track, but, after it became bogged down, a leap-frogging process was begun by which two sets of track were laid and relaid as the locomotive was driven and pulled to the waiting railway track. Her McAlpine green livery is assumed to be GWR Brunswick Green when she takes centre stage on invitation steam days about 12 times a year or is borrowed by other railways outside Fawley’s summer season.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1966, an Avonside Saddle Tank arrived followed quickly by the first rolling stock, a Shunt wagon. These were pulled up the hill in a new way, using a specially constructed sled. Over five decades, Bill expanded beyond the tracks and rolling stock to bring together examples of the equipment found at stations or operating the line, such as signal boxes, water cranes, waiting shelters and footbridges. First came the all important station itself (Fig 1). Bill was made aware of a particularly pretty example, Somersham in Cambridgeshire, on the St Ives to March line, which was about to be demolished under the Beeching Axe. Dating from 1889, it has cream-painted weather-boarding and long fretted valances supported on iron columns and brackets. It was sliced into three, put on low-loaders and brought to Buckinghamshire. One got stuck under a bridge on the M1, but they got it to Fawley and joined it together. Most who see it now think it has always been here.

The waiting room inside is filled with furniture, prints and photographs (Fig 2) that recall railway companies of the distant and more recent past. There is much more, too, in the neighbouring museum sheds (Fig 3) and, for many years, Bill would give his guests — or they could purchase for 20p — an old-fashioned penny to put into a machine that dispensed chocolate (Fig 4). The Fawley Hill Volunteers wear old uniforms, they have whistles; the clocks always give accurate ‘railway time’ and there is a smell evocative of old stations, especially when the fires are lit. When the ticket machine ‘pings’ or the platform tannoy announces a train, those of a certain age will remember the travelling experiences of childhood.

The ‘station yard’ is lined with demilunes of gauged brickwork depicting ‘cherubs’ in various stages of the construction of a railway station (Liverpool Street). These amazing works of art were about to be demolished when a workman downed his pickaxe and refused to do any more damage. Someone called Bill who hot-footed it to Liverpool Street and arranged for McAlpine’s to very carefully remove the remaining brickwork with its stone frames and the cherubs were equally carefully rebuilt at Fawley (Fig 7).

Many of Bill’s architectural acquisitions have intriguing pedigrees and a significant number had already been moved once. One such is a charming signal box, which was originally erected near Burton upon Trent at Swadlincote East in Derbyshire. In 1965, however, it was moved to the mighty Shobnall Maltings, Staffordshire, to become an important part of the extensive railway operated by the brewers Bass, Ratcliff & Gretton. Here the eight miles of track and sidings required the services of their own signal box. The prefabricated methods of the Midland Railway made it an easy job in both cases to take the box to pieces and reassemble it. When it came to Fawley in the summer of 1968, there was a steam crane conveniently in residence to help with the task.

In addition to engines such as Flying Scotsman, Pendennis Castle and others, Bill secured three prize pieces of rolling stock, which now reside at Fawley. First was GE1, a saloon built in 1920 for Sir Henry Thornton, general manager of the Great Eastern Railway. Thornton was Canadian, which explains why his saloon was as well appointed as the contemporary Pullman cars that ferried leading New York families to their summer- and winter-holiday ‘camps’ in the Adirondack mountains in the US, several now resplendent in the Museum on Blue Mountain Lake. (The ‘Royal Canadian Pacific’, now at Calgary in Canada, is equally palatial.) It has an open balcony of the type American Presidents used to give speeches from, a salon with buttoned leather upholstery as resonant as a Pall Mall club, a bathroom, a galley kitchen and a dining saloon that seats 14.

Nearby is a Royal Saloon fitted out in 1948 for the use of the newly married Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, painted in Royal Claret livery. Finally, alongside it, is a 1955 Ladies-in-Waiting Saloon originally built for the then Prince of Wales and The Princess Royal and known as the Nursery Coach. Each of these has a sitting room, four bedrooms and two bathrooms: hitched up with GE1, they formed perfect accommodation for family trips or when — as chairman of the Railway Heritage Trust — Bill travelled through the Shires to oversee the restoration of station buildings all over Britain.

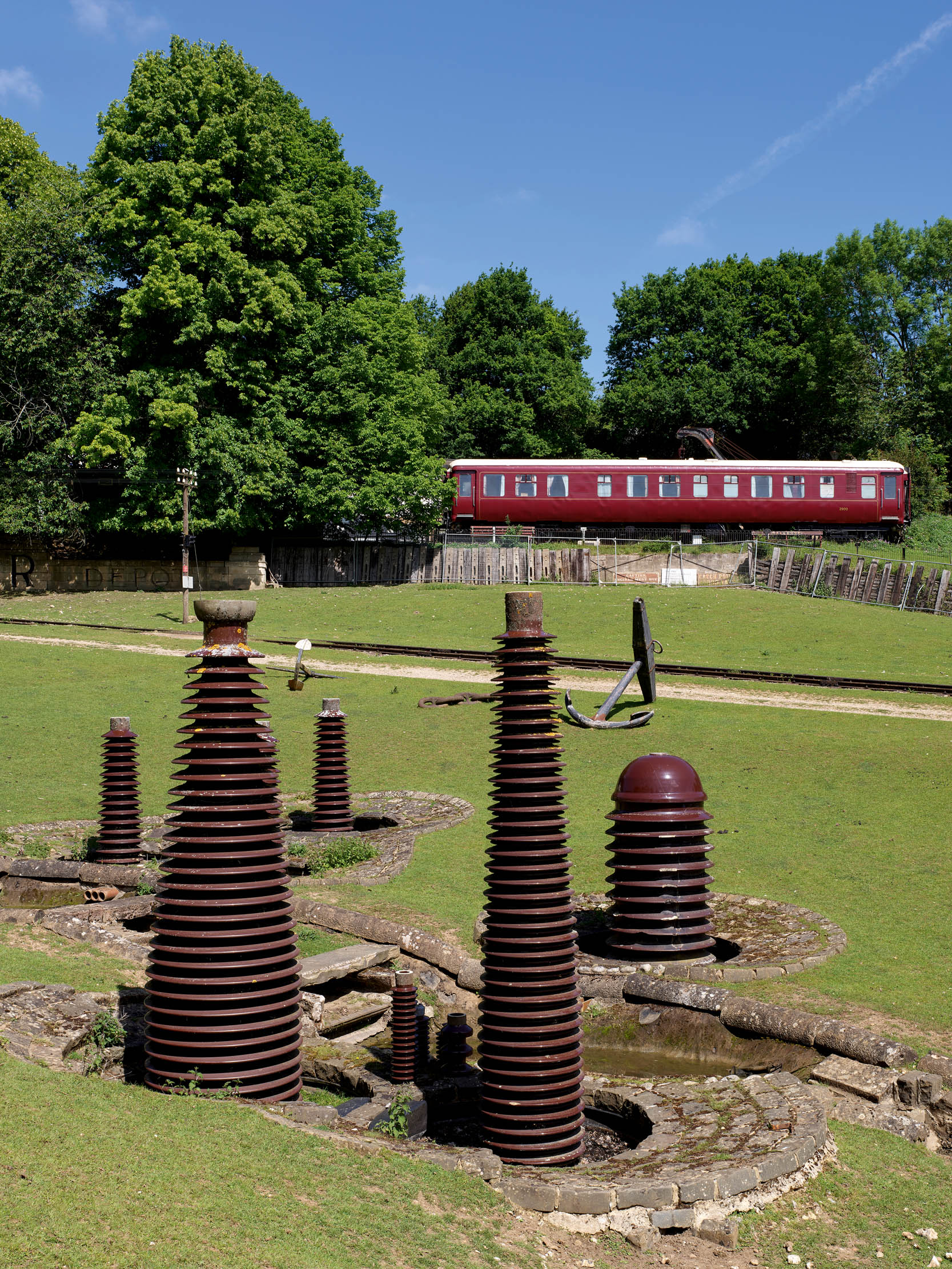

On steam days, it is all aboard. Plunging down the valley under a pedestrian bridge (Fig 5), travellers enjoy a witty tour on a railway theme. First on the right are bubbling fountains made from giant power-station insulators looking rather like Daleks (Fig 6). With them are two concrete flagpoles from the original Wembley Stadium, which was built by McAlpine’s. Another big eyecatcher is one of the magnificent iron abutments from old Blackfriars Railway bridge inset with the brightly painted crest of the London Chatham and Dover Railway, which opened in 1864. Next come the solid iron parapets from two railway bridges on the Reading to Wokingham Line, then the handsome stone arches that formed the Taxi entrance to Waterloo Station, before the arrival of the Eurostar. Moments later, passengers are confronted with a cast-iron sign pointing to Scotland and England in opposite directions.

The journey to Scotland terminates, appropriately, at the Inverernie Waiting Shelter (actually from Thrapston, Northamptonshire, but named for Ernie, a long-serving Volunteer) and a genuine signal box from the Highlands — from Invergordon, north of Inverness, dating from 1890. It arrived at Fawley in 1986 and again honours an early Volunteer. Without the stalwart army of Volunteers who enjoy ‘playing with Bill’s train set’, the railway would not run, but run it does, obeying all the rules of any other railway in Britain.

As certain Georgian parks, such as Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire, had monuments or temples to Cloaca (goddess of drains, as well as pure water) Bill put in a platform named ‘Sewage Works Halt’, where passengers can hop off to get to the swimming pool. Rarely do they realise that there really is a sewage works, out of sight below the line.

Fawley Hill’s most impressive monument is one of its most recent, Ironhenge (Fig 8). When St Pancras Station was being transformed for the Eurostar, a new departure hall had to be created with openings for lifts and escalators. This involved removing some of the hundreds of cast-iron columns that support the tracks and platforms. The undercroft space was originally used for storing best Burton ale and the distance between the columns was governed precisely by the dimensions of the casks.

Inevitably, Bill was asked if he would like some of the undercroft columns and he requested six, with the beams they supported. The delivery brought 42. Lady McAlpine observed ‘well, there is Stonehenge and Woodhenge — why not Ironhenge?’ And so — using the surplus 36 columns — it came to be.

The creation is particularly appropriate at Fawley because, just across the Thames, in another landscape park, is Little Master Stonehenge, a ring of ancient stones brought by Gen Conway from the Channel Island of Jersey, where they had been in the line of fire from a large artillery fort he was constructing. Those stones are now listed. Surely, Ironhenge will soon be as well.

Visit www.fawleyhill.co.uk to find out more.

Fawley Court: A house by the Thames bearing the fingerprints of Wren and Wyatt

Two of Britain’s greatest-ever architects, Christopher Wren and James Wyatt, have been linked with the creation of Fawley Court.

Credit: Strutt & Parker

A gorgeous Berkshire house/castle-hybrid that inspired Thomas Hardy to write 'Jude The Obscure'

Penny Churchill takes a look at Fawley Manor, a glorious 17th century house that's come up for sale.

Cumberland Lodge: The 17th century marvel 'a thousand times more agreeable than Blenheim'

This year, a remarkable educational foundation in a spectacular parkland setting celebrates its 70th anniversary. John Goodall considers the history

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwback

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwbackTactfully revived, Dennis Severs’ House defies categorisation, finds Jeremy Musson.

By Jeremy Musson

-

The Castle of Mey: Inside the Queen Mother's beloved home in Scotland

The Castle of Mey: Inside the Queen Mother's beloved home in ScotlandA visit to Scotland in the first months of her widowhood encouraged The Queen Mother to buy and restore a castle. John Goodall describes the history of the building and the achievements of the trust that has managed it for the past 22 years.

By John Goodall

-

Britain’s great railway stations: Victorian eclecticism, modern genius and one that is a true work of art

Britain’s great railway stations: Victorian eclecticism, modern genius and one that is a true work of artSimon Jenkins lauds our most romantic and architecturally significant railway stations, some of the unsung triumphs of British conservation.

By Country Life

-

Sandycombe Lodge: The house that JMW Turner created, restored just as he designed it, now open to the public

Sandycombe Lodge: The house that JMW Turner created, restored just as he designed it, now open to the publicA breathtaking amount of work has gone into re-creating Sandycombe Lodge, the house that Joseph Turner designed and lived in for much of his life.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

What next for Clandon Park? Time to breathe life back into this great house

What next for Clandon Park? Time to breathe life back into this great houseSimon Jenkins, former chairman of the National Trust, considers the next steps for Clandon Park in Surrey, two years after the fire that reduced it to a ruin.

By Country Life

-

Kedleston Hall: A National Trust gem restored to its extraordinary former glory

Kedleston Hall: A National Trust gem restored to its extraordinary former gloryIt's 30 years since the National Trust raised the money to buy Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire. The work done since then is nothing short of staggering.

By Country Life

-

250 years of Bath’s Royal Crescent: From Druidic influences to big screen fame

250 years of Bath’s Royal Crescent: From Druidic influences to big screen fame2017 marks 250 years since the first foundation stone was laid.

By Agnes Stamp

-

Clandon Park after the fire: The National Trust’s largest ever reconstruction project

Clandon Park after the fire: The National Trust’s largest ever reconstruction projectUntangling the Gordian Knot.

By John Goodall