The John Rylands Library: How one of Britain's great libraries was created by a forward-thinking widow

The widow of a successful industrialist turned her inherited fortune towards the creation of one of Britain’s greatest libraries: The John Rylands Library, Manchester. Steven Brindle explains the story of her foundation and admires the library’s architectural splendour, with photographs by Will Pryce.

Deansgate, the long street that runs up the west side of Manchester city centre, follows the line of a Roman road. Today, it is lined with tall commercial buildings interleaved with modern developments.

One tall Gothic building stands out among the temples of commerce: of red sandstone, towered and battlemented, but with traceried windows and octagonal turrets, like a cross between a fortress and a great church.

This is the John Rylands Library, now part of Manchester University Library, one of the great research libraries in the world.

The library was begun in 1890 by Enriqueta Rylands (1843–1908) as a memorial to her husband, John (1801–88), one of the most successful businessmen in British history. His career epitomised the rise of the cotton industry that, more than any other, defined Victorian Manchester. John Rylands was born in 1801, the youngest son of Joseph, a modestly successful textile manufacturer. He entered the family business, Rylands & Sons, working as a salesman and a wholesaler.

With his phenomenal business acumen and capacity for work, Rylands gradually became the dominant figure in the firm: in his twenties, he worked 19-hour days; in his seventies, he still worked 12-hour days. By 1842, he was in charge of the firm, which shifted from linen into cotton, opened more and larger mills and moved into the dyeing and bleaching business.

In the 1850s, he was Manchester’s largest textile merchant and first millionaire. By 1865, Rylands & Sons was the largest textile manufacturer in Britain, with 4,500 employees. The firm kept growing: in 1873, it became a joint-stock company; by this time, it incorporated every stage of the manufacturing process, through spinning, weaving, bleaching and dyeing and the manufacture of textile machinery and was also expanding into making clothing.

Rylands was not the kind of manufacturer to abandon his roots: he settled at Stretford, just outside the city, building an Italianate house called Longford Hall. He declined to keep horses, hounds or manservants, although he did employ 19 gardeners at the hall. His family life was repeatedly struck by tragedy: he and his first wife, Dinah Raby, had seven children, but Dinah died in 1843 and all his children predeceased him. Rylands had become a devout Christian in his twenties and, as a Congregationalist, was convinced that congregations should be able to study the Bible and worship independently. To this end, he became interested in Biblical scholarship and published three editions of his own ‘Rylands Paragraph Bible’. He also amassed and published hymns and was active in charitable works. He was a major benefactor to Ainsworth, Gorton, Greenheys and Stretford and made special provision for widows, orphans, and the aged poor, much of it secretly.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1848, Rylands married a second time, to Martha Carden. They had no children, but Martha was a fervent supporter of his religious activities and brought with her a lady’s companion: Enriqueta Augustina Tennant (1843–1908). Enriqueta was born near Havana, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant, but little is known of her early life. After her father’s death, she was brought up in Paris and, at some point, also became a devout Congregationalist. Martha died in 1875 and, less than a year later, the 74-year-old Rylands married Enriqueta, 40 years his junior. The couple adopted two children, Arthur and Maria. When Rylands died in 1888, one of the richest men in Britain, the bulk of his estate, valued at £2,574,922, went to Enriqueta. She decided to commemorate him by founding a large theological library in Manchester, for non-conformist ministers and laity.

By 1890, Mrs Rylands had chosen an architect: Basil Champneys (1842–1935), the son of the Anglican rector of Whitechapel. He had designed several educational buildings, including Mansfield College, Oxford (1887–90), an institution with Congregationalist and Mancunian connections, probably his point of connection with the widow. She particularly admired Mansfield’s library, which was the model for her very much larger foundation. In 1892, Mrs Rylands bought the vast antiquarian library at Althorp, Northamptonshire, of 43,000 volumes, for £210,000. It had mainly been formed by the 2nd Earl Spencer (d. 1834) and possessed an unrivalled collection of early Bibles, as well as early printed editions of Greek and Latin classics. The collection had to be catalogued for insurance, so Mrs Rylands appointed Edward Gordon Duff as her first Librarian.

Building the library took 10 years, and cost £224,086 against an initial estimate of £78,000. Mrs Rylands was closely involved the whole time. It was opened on October 6, 1899, the 24th anniversary of her marriage to John Rylands, by the principal of Mansfield College. Mrs Rylands seems to have had a tense relationship with both her architect and her librarian: Duff resigned in 1900 and, soon afterwards, in 1901, she bought all the manuscripts from the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, the celebrated library of the Earls of Crawford and Balcarres, for £155,000. Hitherto kept at Haigh Hall in Lancashire, it was the only private library that rivalled or surpassed Earl Spencer’s. As a manuscript collection, it was quite different in character to the Spencer Library: it included 6,000 rolls and codices, including works in Hebrew, Greek and several Oriental languages.

As her husband had been, Mrs Rylands was of a retiring disposition and shunned fashionable society. She was, however, involved in every aspect of the library’s foundation, drawing up its regulations and choosing its motto: Nihil Sine Labore (nothing without labour). It began publishing a bulletin in 1903 and developed as a leading research library.

The Lancashire textile industry was booming and Mrs Rylands was evidently a shrewd businesswoman, for, on her death in 1908, despite having spent almost £1 million on her library, she left an estate of £3,448,692. Much of this was left to charities of various kinds, hospitals, ragged schools, women’s charities, and educational foundations, as well as a £200,000 endowment for the library.

The value of this endowment, however, declined with the Lancashire textile industry. In 1972, the library’s trustees handed it over to the Victoria University of Manchester and the building on Deansgate became the home of the university’s combined Special Collections. The increased size and pressure of use eventually demanded changes. In 2003–07, a major project was carried out at a cost of £17 million, partly funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, to create a new entrance, storage and research facilities, designed by Lloyd Evans Prichard and Austin-Smith:Lord.

As a result, Champneys’s spectacular twin-towered entrance façade overlooking Deansgate is no longer in normal use. The building occupies a long narrow site and the original intention was to give the building a pitched roof. This was left off, however, owing to fire concerns and a thick concrete roof laid instead. It leaked and one major achievement of the 2003–07 work was to install a fireproof, pitched roof, completing Champneys’s original design a century on.

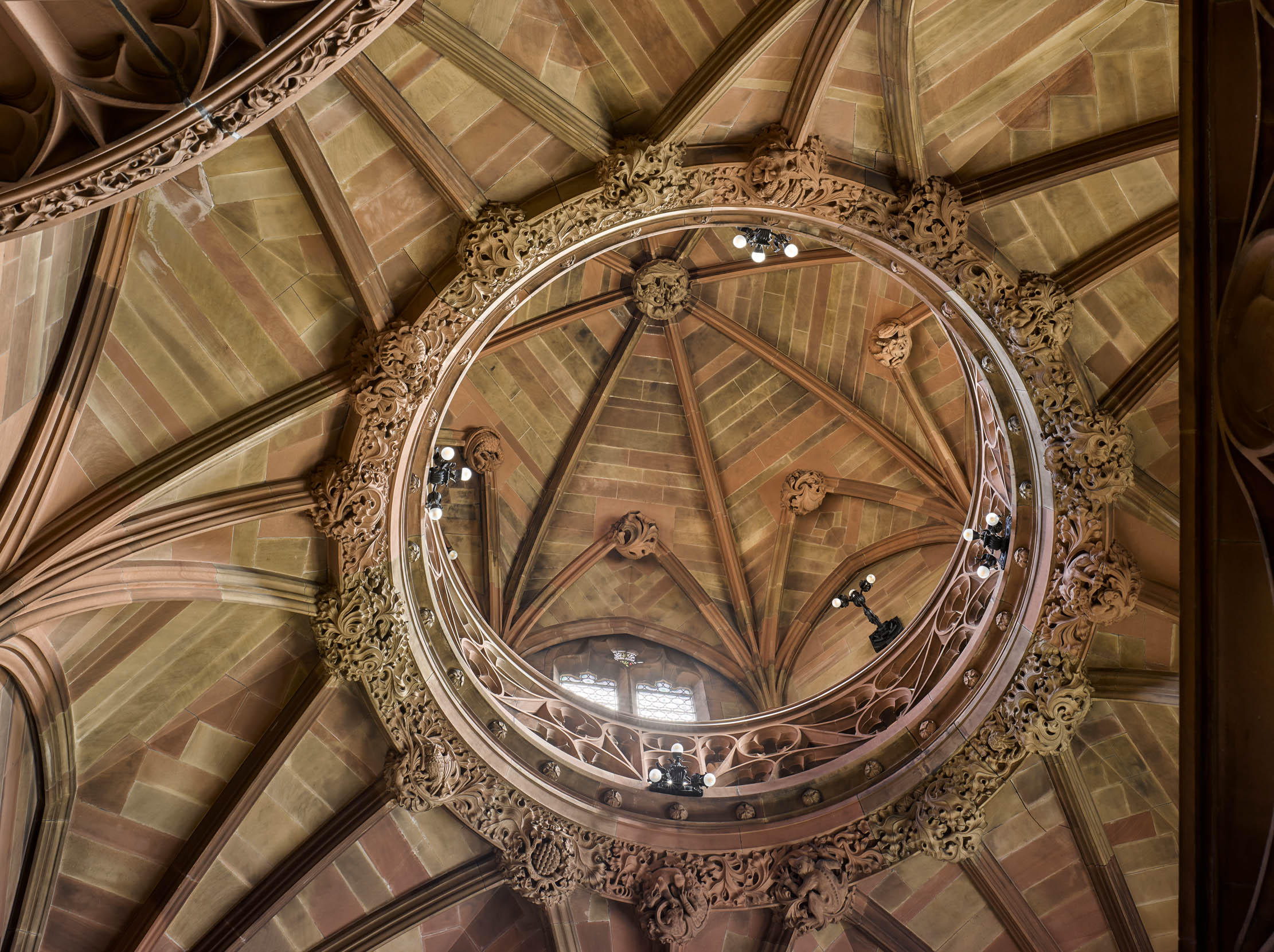

Passing through the original entrance, visitors arrive in the double-height entrance hall, which Champneys designed with steeply pointed arches and vaulting. The idiom of the architecture is predominantly Gothic of about 1300, as may be seen at the cathedrals of Chester or Lichfield. Ahead is a vaulted niche with an allegorical sculpture, Theology Directing the Labours of Science and Art, by John Cassidy. The upper ground floor was designed to house lecture and meeting rooms, as well as a lending library, although it seems that the latter never really functioned. These rooms now house changing exhibitions from the library’s remarkable collections.

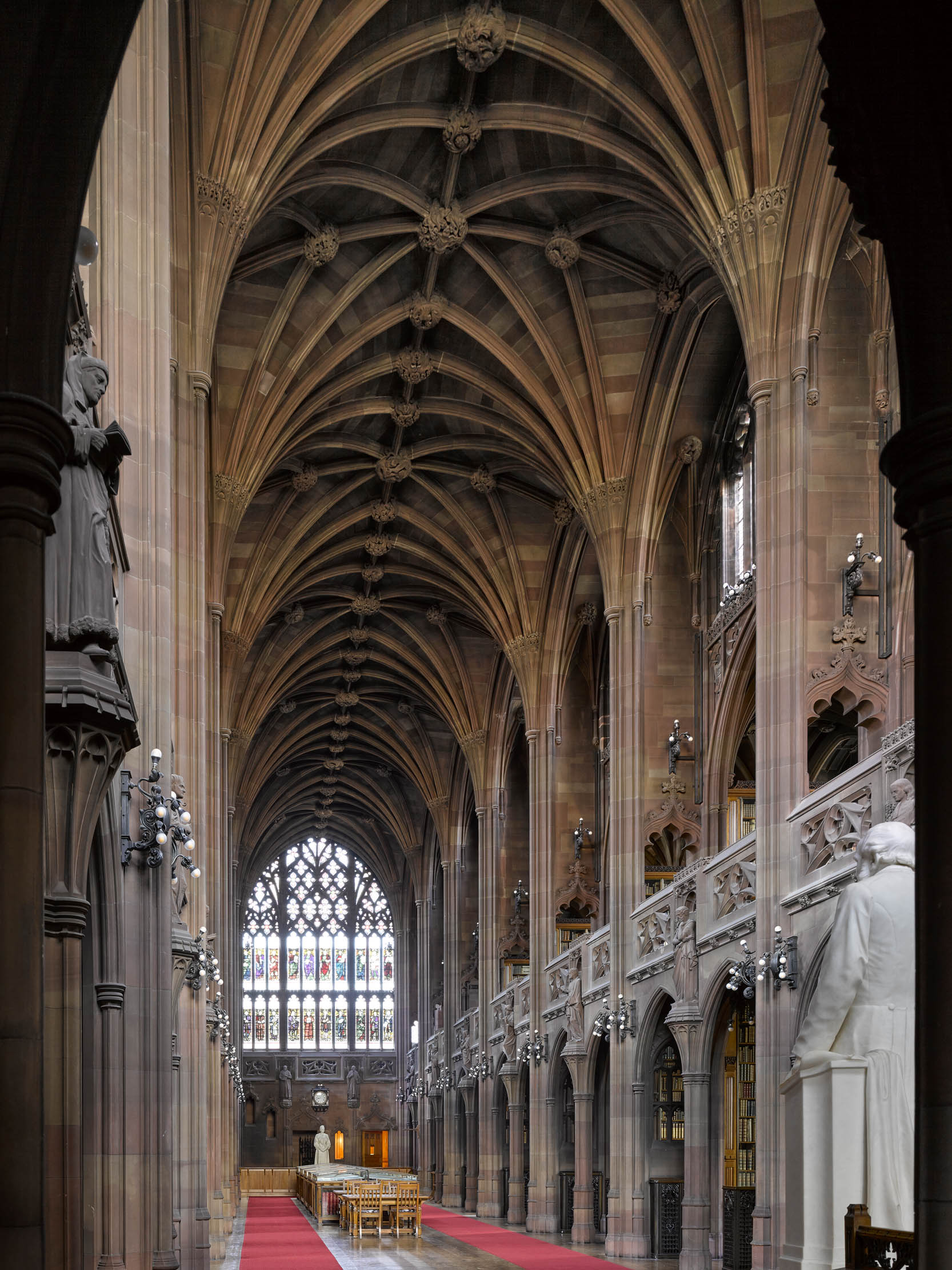

The staircase rises from the entrance hall in several stages. After the drama of the ascent, the main Reading Room is serene and almost ecclesiastical in feeling. It is high and cathedral-like, eight bays long, with stone tierceron vaulting in two contrasting shades of stone. Huge, traceried windows with stained-glass figures of philosophers, writers and artists by Charles Eamer Kempe fill the upper part of both end walls. The central volume, meanwhile, is lit by high, clerestorey windows of clear glass.

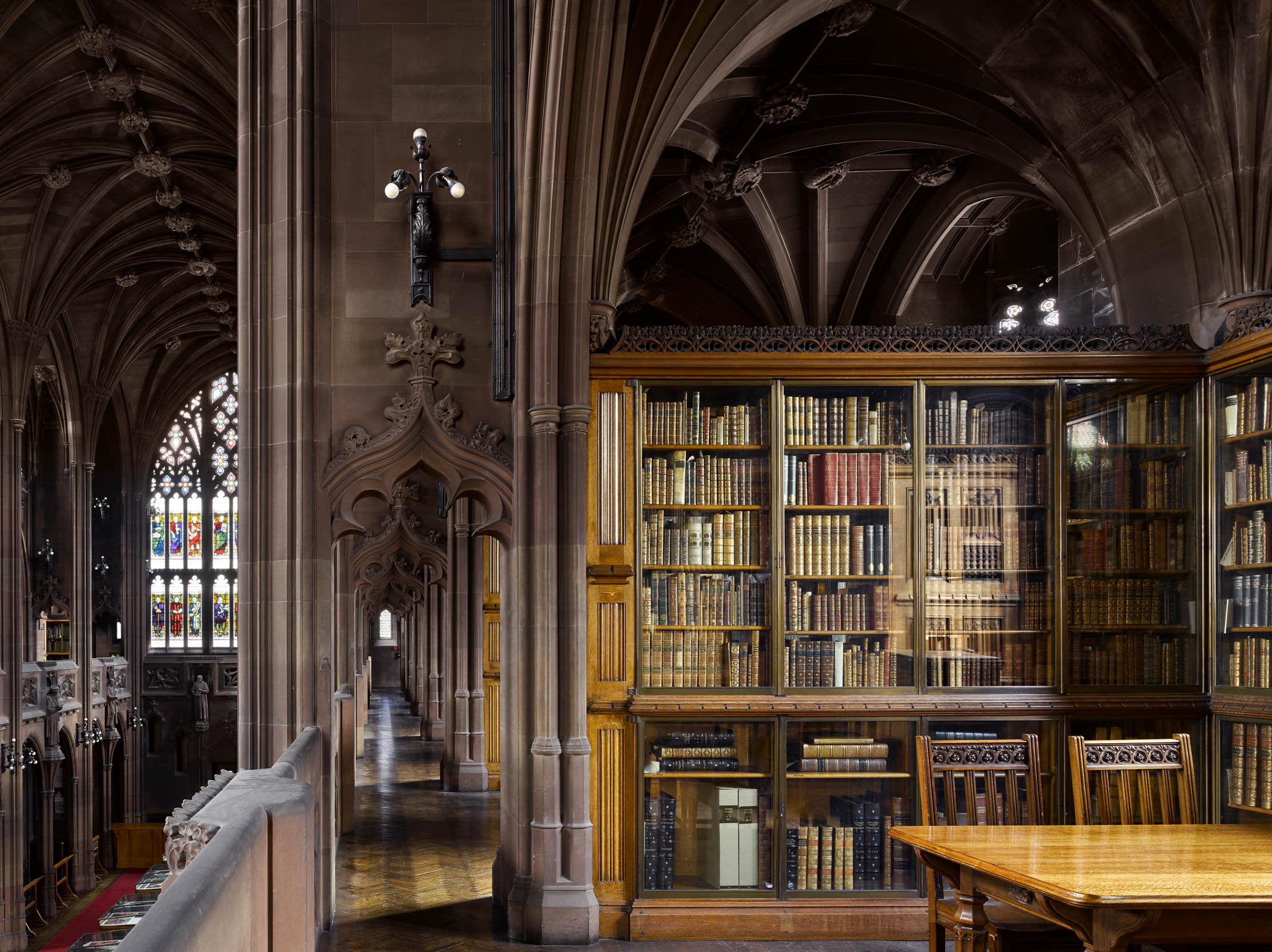

Opening off the sides of this central nave are deep bays on two levels, also lit by clear windows. Each is furnished with bookshelves and a window carrel for readers, a composition reminiscent of 16th-century depictions of the study of St Jerome. The general scheme may have been inspired by John Loughborough Pearson’s great church of St Augustine, Kilburn, in London.

Champneys and Mrs Rylands disagreed about matters of detail and not all of the finishes are by him. The mid piers of the lower arcades support statues of literary and religious figures, which she commissioned from Bridgeman’s of Lichfield. Mrs Rylands also had the furniture designed by the clerk of works, Stephen Kemp. Particularly splendid are the bookshelves, exactingly made with glazed fronts set in locked metal doors with a velvet seal.

The bronze railings and light fittings, by Singer’s of Frome, are notably successful, and introduce a touch of contemporary Art Nouveau into this grand, but otherwise rather conservative scheme. White marble statues of John and Enriqueta Rylands, also by John Cassidy, look down the main nave of the Reading Room from pedestals at the lower level, at either end.

The John Rylands Library has developed well beyond Mrs Rylands’s initial vision. As a major archive and research library, it has acquired a great many other special collections since her death. The library today houses more than 1.4 million items, including vast collections of manuscripts and archives, as well as early and rare books.

It is impossible to do more than hint at the wealth and range of its collections. The library is home to the finest collection of the works of the printer Aldus Manutius in existence and the second-finest collection of Caxton’s. The manuscript collections span 5,000 years and more than 50 languages. A merger with the University Library brought the Christie Library, another great collection of early printed books, into its fold together with specialist collections, in particular in medical history and the archive of the Manchester Guardian.

The library has also become a major local and regional archive: the papers of several local landed families—such as the Egertons of Tatton, the Booths and Greys of Dunham Massey and the Leghs of Lyme — are deposited here. There are major archives relating to literary history and the history of the Manchester area, to business and industry, trade unionism and non-conformism. The library maintains a programme of changing exhibitions from its remarkable collections, which rival those of the Oxford and Cambridge libraries in their range and importance.

Manchester has long had a reputation as a centre of education and learning, as well as a centre of commerce, and this continues to be embodied in its remarkable libraries: the Central, the University, Chetham’s, the Portico — and the John Rylands Library. The magnificent Gothic building on Deansgate remains a beacon of intellectual, artistic and spiritual values, a reminder that commerce and wealth may make all this possible, but they are not everything: as its founders intended.

Find out more about the John Rylands Library at www.library.manchester.ac.uk/rylands

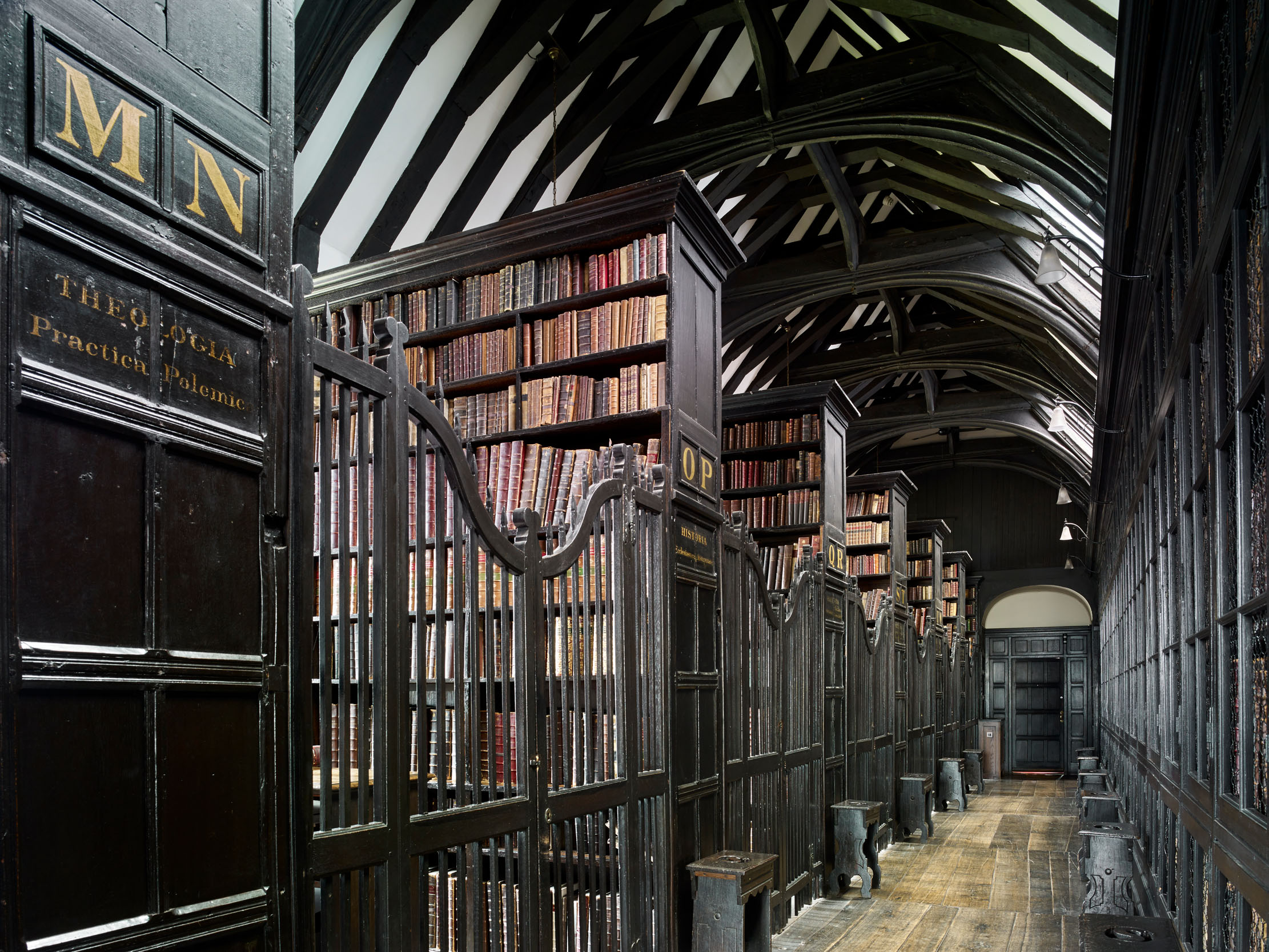

Chetham's: Inside the oldest public library in the English-speaking world

The buildings of a wealthy medieval college were transformed during the 17th century into a school and what is now

The exceptional tale of Manchester Town Hall, a Victorian masterpiece that's the finest building of its kind in Britain

In 2018, the celebrated Manchester Town Hall closed for a six-year renovation. Country Life recorded its empty interiors before work

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes