The houses of Sherlock Holmes: How Arthur Conan-Doyle's architectural savvy shaped literature's greatest sleuth

Sherlock Holmes had an eye for architectural detail, an interest derived from his creator, Arthur Conan Doyle. Jeremy Musson looks at how it emerges in the books, with the help of specially commissioned drawings by Matthew Rice for the Country Life Picture Library.

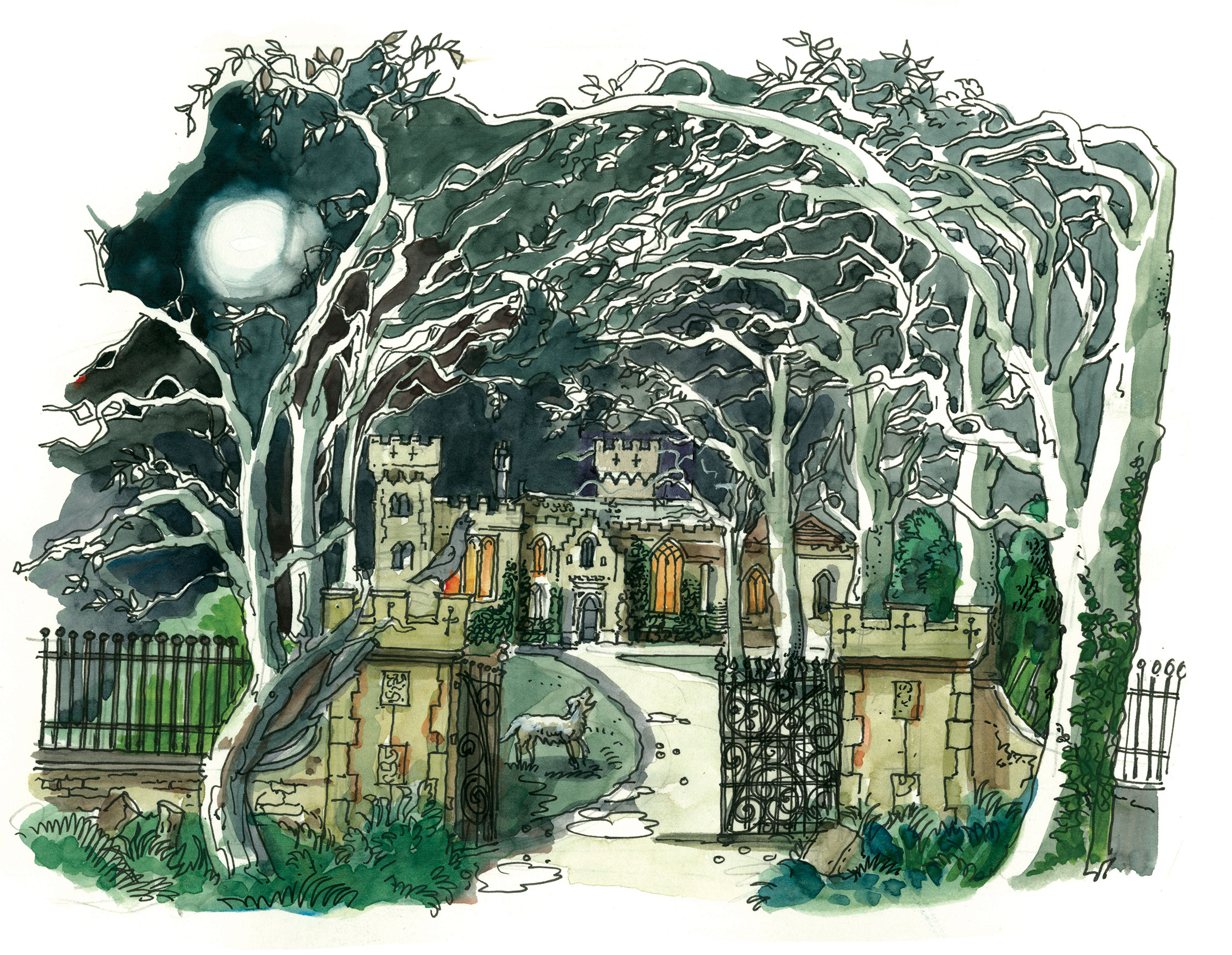

Dartmoor’s Baskerville Hall is one of the most famous country houses in English fiction. The arrival at its doors of Dr Watson, in the company of Sir Henry Baskerville, is a vivid piece of cinematic direction, artfully combining the Gothic horror tale with the more modern taste for detective thrillers.

Passing a ruined black-granite lodge, Watson and Baskerville go through the gates that are ‘a maze of fantastic tracery in wrought iron’ before reaching an avenue where ‘old trees shot their branches in a sombre tunnel’. The hall is a ‘heavy block’, with a projecting porch, its façade ‘draped in ivy’ within which the odd window or heraldic display can be seen.

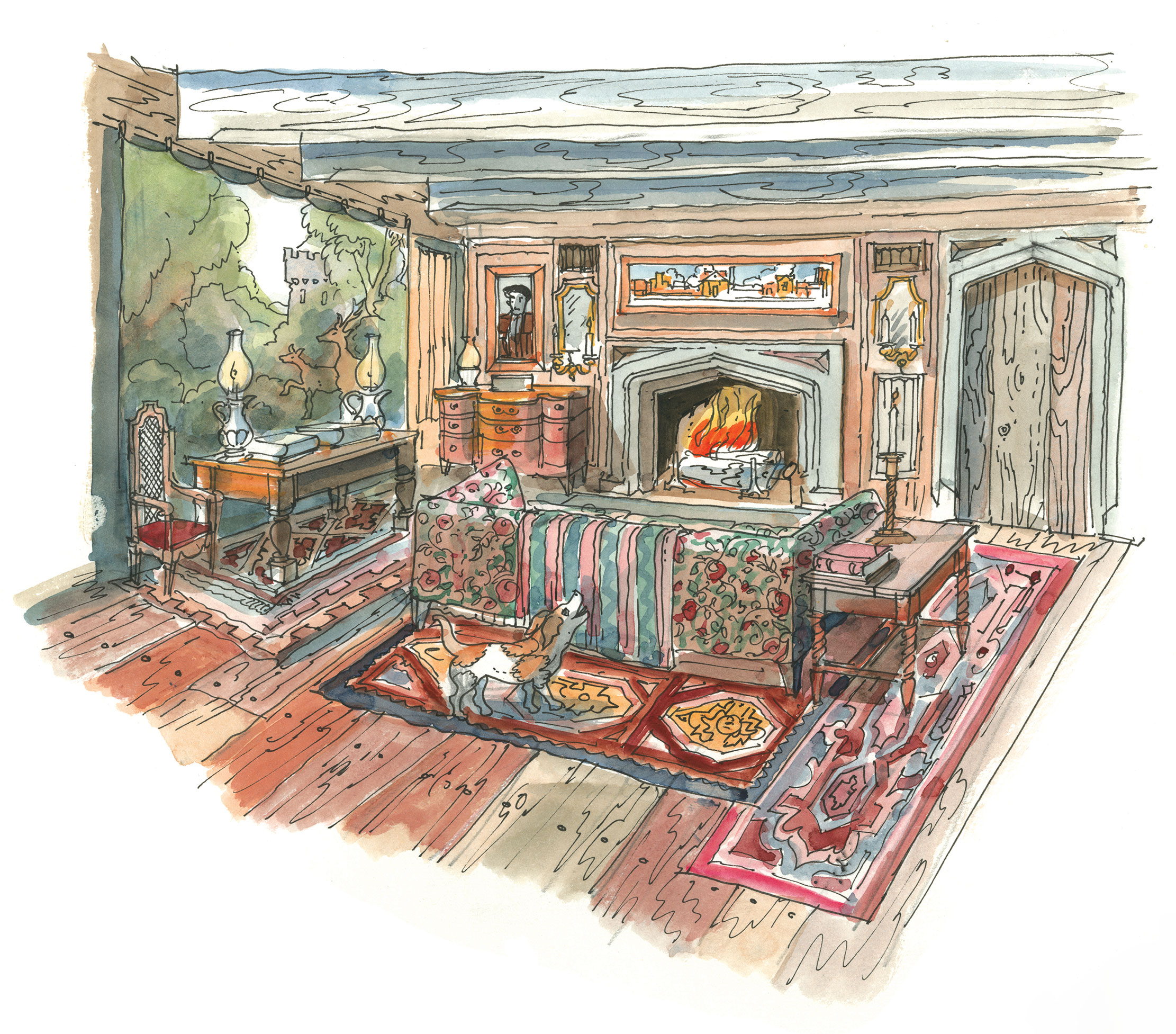

The central block is framed by turrets, beyond which there are modern wings built in more black granite. The young Sir Henry, ushered in by the butler Barrymore, is touched by the atmosphere of the great hall. As they warm themselves before a fire, he speaks of it as ‘the very picture of an old family home’.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s rendering of architectural aesthetics show a good grasp of the qualities of old English architecture as it was admired and imagined by the late Victorians. Inside Baskerville Hall, Watson, a retired military doctor, finds himself immediately conjuring up images of an ‘old-time banquet’ and is daunted by portraits of a ‘dim line of ancestors, in every variety of dress’.

The accidentally overheard sound of the housekeeper sobbing is pure Edgar Allan Poe, but rays of morning sun in which the panelling ‘glowed like bronze’ transform these first impressions.

Conan Doyle’s acuity to historic English houses is revealing and beguiling, not least because it echoes the themes of the early architectural coverage of Country Life (first published in January, 1897). The Hound of the Baskervilles first appeared in 1901, as a serial in The Strand Magazine — published by Sir George Newnes in the same stable as Country Life — and its runaway success in book form persuaded Conan Doyle to revive his great detective, who was last heard of grappling with Moriarty by a waterfall in a story published in The Strand in 1893.

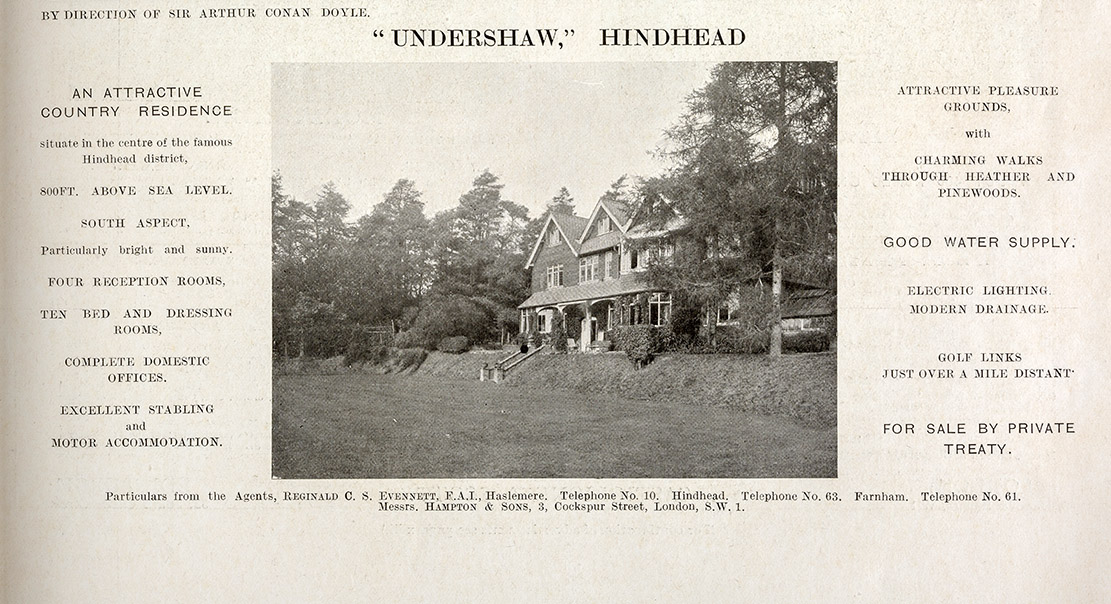

However, when Conan Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles, he lived in a handsome, modern (with electric light) country house called Undershaw, built for him near Hindhead, Surrey, in 1897, in the fashionable Old English/Queen Anne Revival mix made popular by Norman Shaw.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The house is on an elevated site that offered breathtaking views and was chosen to cater for the delicate health of Conan Doyle’s wife, whose TB had obliged her to live in Switzerland for a time.

Now occupied by a school, Undershaw could not have been more different from the imposing and haunting Baskerville Hall. It was light, healthy and comfortable — cottage-like, even — with its gabled and clay-tiled roof and tile-hung elevations echoing the Surrey-Sussex vernacular. Conan Doyle’s letters imply he himself had quite a hand in the design, but, in order not to be taken for a ride by builders, he appointed his old friend, the architect J. H. Ball — whom he described in a letter to his mother as ‘a man of most fastidious taste’.

He sketched out a plan of the main rooms in the same letter (May 25, 1895), noting ‘the sun will be in all the rooms (to the south) all day’ and added that he and his wife ‘would take a pride in the house & furnish it lovingly’. Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, visited Undershaw in 1907 and described it as ‘cozy and snug to a remarkable degree’, its rooms and furnishing creating an effect that was like a ‘fairy pleasure house’.

Conan Doyle first met Ball — a pupil of Waterhouse — in Portsmouth, when he was beginning his career as a doctor and Ball was starting out as an architect (remembered today for Portsmouth’s St Agatha’s Church, a remarkable Anglo-Catholic shrine). But Conan Doyle had been interested in architecture from childhood; his father Charles Altamont Doyle had been a promising artist who worked as an architectural draughtsman in the Scottish Office of Works and designed the fountain at Holyrood Palace.

Charles Doyle struggled with depression and alcohol addiction, spending many years in an asylum, but his artworks were admired, not least by Bernard Shaw. Many of his architectural views of Edinburgh are now in the National Galleries of Scotland’s collection.

Raised a Catholic, Conan Doyle was whisked off to boarding school, and some have argued his vision of Baskerville Hall was shaped by the ancient gentry house that has been occupied by the Jesuits and Stonyhurst College since the 18th century.

Conan Doyle took a genuinely active interest in architectural design. He prepared sketches in 1912 for an extension to a country house-turned-hotel near Lyndhurst in Hampshire and, two years later, designed a golf course and hotel in Canada’s Jasper National Park.

In 1907, he also acquired a fairly new house — Windlesham, near Crowborough in West Sussex — which was remodelled by local architect Langton Dennis to create a home for him and his second wife, Jean Leckie, whom he had married on September 18, 1907 (after being in love with her for 10 years), one year after the death of his first wife.

To Windlesham was added a 39ft music room where Jean played, and the room also served as a ballroom and drawing-room. The house is described in Andrew Lycett’s 2007 biography Conan Doyle: the Man who Created Sherlock Holmes as being in ‘Arthur’s favourite baronial style, surrounded by paintings... incongruous hunting mementoes and an open log fire’.

In 1925, the Conan Doyles acquired an ‘old-fashioned Cottage Residence’, Bignell Wood in Hampshire’s New Forest. Lycett reports that this, too, underwent ‘an expensive transformation, as various buildings had been knocked together’. Intriguingly, similar renovations hover in the background of The Hound of the Baskervilles, where Watson is pleased to observe Sir Henry Baskerville has spoken to a contractor in London and is in communication with ‘the architect who prepared plans for Sir Charles’.

Holmes had already noted a newspaper article about Sir Charles Baskerville returning from South Africa with a large fortune and schemes of ‘reconstruction and improvement’ — it is clear the paper approves the of idea of a member of an old gentry family returning to ‘restore the fallen grandeur of his line’.

Watson also muses on Sir Henry Baskerville’s love for Miss Stapleton of neighbouring Merripit House, an old stone farmhouse ‘now put into repair and turned into a modern dwelling’. The description calls to mind many of the smaller country houses featured in Country Life in the early 1900s. Its large rooms are ‘furnished with elegance’ under Miss Stapleton’s influence, perhaps echoing Conan Doyle’s own approach to buildings and his reverence for his wives’ taste in decoration.

In The Problem of Thor Bridge (1922), Mr Gibson, an American senator-turned-South American gold-mining magnate, owns a Hampshire estate called Thor Place, a ‘widespread, half-timbered house, half Tudor and half Georgian’. Although not described, we can imagine interiors designed at the height of luxury, worthy of a Randlord such as Julius Wernher at Luton Hoo, perhaps by a designer such as Mewès and Davies.

The handsome gentry houses that appear in many Holmes stories are rarely in such good condition. Most sinister is the decaying manor house of Stoke Moran on the western border of Surrey in The Adventure of the Speckled Band (1892).

Here, a crazed squire has retired after a medical career in India to a house where ‘only one wing is now inhabited’ and which has lichen-blotched stone, a high central portion and two curved wings ‘like the claws of a crab’. With one side boarded up and the roof partly caved in, it is ‘a picture of a ruin’ — again, we are in the world of Poe. Holmes even suggests they pose as visiting architects.

Holmes and Watson also visit the home of a London tea broker and his Peruvian wife, in The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire (1924). The couple’s house — Cheeseman’s in Lamberley — is an ancient farmhouse ‘with towering Tudor chimneys and a lichen-spotted, high-pitched roof of Horsham slabs’. Old in the middle and newer at the wings, laden with heavy beams, there is on everything ‘an odour of age and decay’.

Less decrepit is the Manor of Hurlstone in West Sussex, which appears in The Musgrave Ritual (1893). The family have been established there since the 16th century and it is considered ‘the oldest inhabited building in the county’. When the owner arrives at 221B, Baker Street, Holmes decides something of his alert physical presence is impressed with qualities associated with his old family home: arches, mullioned windows and ‘all the venerable wreckage of a feudal keep’.

A rambling house of long corridors, bristling with ‘trophies of old weapons’, its L-shaped plan has an older wing, now used as stores, and with the date 1607 carved over the door. There is a new wing from ‘the last century, meaning the 18th century’, which forms the habitable part of the house.

Conan Doyle clearly relished such Pevsner-like details and the same collection includes The Adventure of the Abbey Grange (1904), which sets a murder in a low, wide house in the country of Kent, ‘pillared in front after the fashion of Palladio’, with a centre ‘of great age’ and a newly added wing.

A particularly beguiling description appears in The Valley of Fear (1914). The Manor House of Birlstone ‘on the northern border of the county of Sussex’ is thought to date back to the times of the First Crusade ‘when Hugo de Capus built a fortalice in the centre of the estate’. In 1543, the original fortified house was destroyed by fire, but ‘its smoke-blackened corner stones were used, when, in Jacobean times, a brick country house rose upon the ruins of the feudal castle’.

It is described as being early 17th century, with its moat fully restored — ‘a fact which had a very direct bearing upon the mystery which was soon to engage the attention of all England’. (Holmes deftly solves the mystery by reading the guidebook.) Early Holmes scholar H. W. Bell argued that this description was inspired by moated Brambletye in Sussex, but, in the 1950s, James Montgomery found an original signed copy of the book, dedicated in Conan Doyle’s own hand and confirming that Groombridge in Kent was ‘the house herein described’.

No such find has fixed a single inspiration for Baskerville Hall and many houses round Britain have claimed the honour, but the likely field examined in Philip Weller’s magisterial The Hound Of The Baskervilles: Hunting the Dartmoor Legend (2002), is relatively small.

Conan Doyle visited Dartmoor with Bertram Fletcher Robinson, a writer friend who first regaled him with the tale of a phantom hound and whom Conan Doyle generously credited with giving him the idea (Robinson also employed a coachman named Harry Baskerville). Weller explores various inspirations for the hall, including Fowlescombe Manor near Ugborough, in Devon — a house already in decline in 1901 and since fallen into ruin — which was possessed of a projecting porch and two towers.

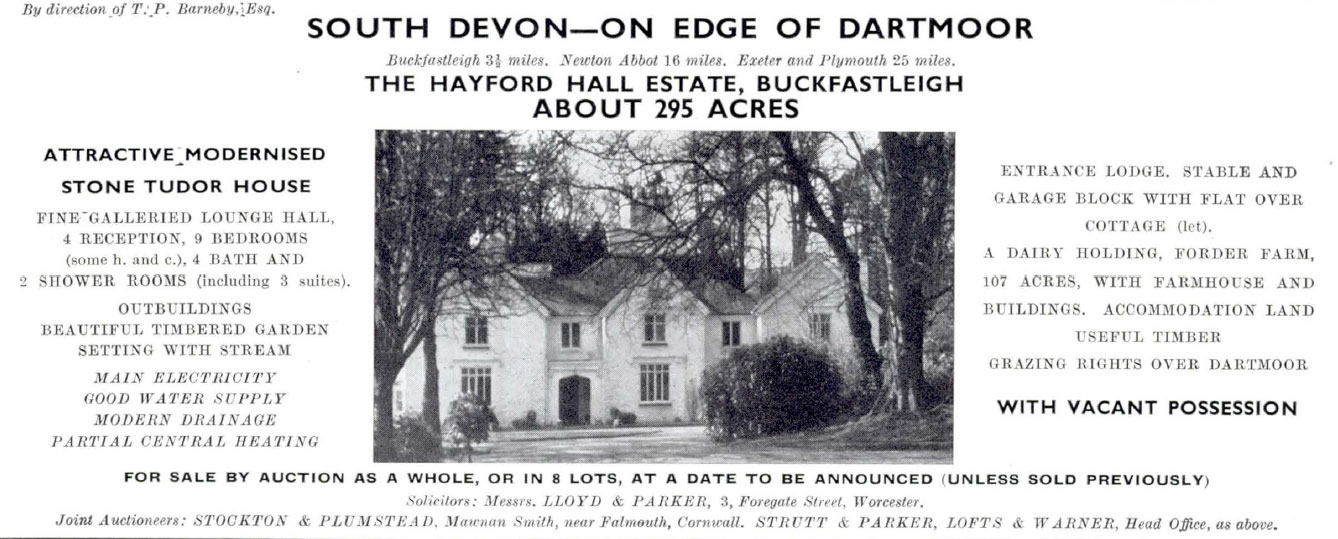

Another candidate is Hayford Hall, west of Buckfastleigh, which, like Baskerville, has an old yew avenue (scene of Sir Charles’s death), but is otherwise not very similar.

Brook Manor, also close to Buckfastleigh, is famously the home of ‘Dirty Dick’ Cabell (who married a daughter of Fowlescombe) a wicked fellow who, according to legend, was hunted to death by a phantom hound on Dartmoor.

It seems likely the most eerie stately home in English fiction was in fact something of an amalgam, combining the Devon houses mentioned and that ‘great old place’ of the English imagination, ever more a symbol of English stability in a politically fraught world — fictional as it always was.

Acknowledgements: Andrew Lycett, author of ‘Conan Doyle’ (2007); Jon Lellenberg, co-editor of ‘Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters’ (2007); Timothy Johnson; and Derham Groves. Story quotations from ‘The Complete Sherlock Holmes’

Sherlock Holmes hits a milestone – test yourself with the ultimate Sherlock quiz

Tim Symonds, author of five Sherlock Holmes novels, is your quizmaster.

Jason Goodwin: Dogs, lichen inspectors and the ticks that look like Hitler

Our columnist Jason Goodwin feels the thrill of meeting a true subject matter expert — and comes across away with

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson