The history of Covent Garden: 500 years of the world's most famous market

It’s half a century since Covent Garden’s eponymous market travelled south of the River Thames, but it did little to dent the area’s appeal. Jack Watkins charts the history of Covent Garden from Tudor times to the present day.

The autumn of 2024 marks the date, 50 years ago, that Covent Gardens’s fruit, flower and vegetable market moved to Vauxhall, leaving the central piazza unused and the future of the entire quarter uncertain. There had been debates about the market, which had long outgrown its location, for decades. In 1968, a council plan held the prospect of mass demolitions to make room for a conference centre, hotels, elevated pedestrian walkways and, in an age when the car was top priority, a sunken four-lane carriageway. The angry reaction of locals galvanised a lengthy campaign demanding, and eventually achieving, recognition of the integrity of the area and of the needs of people who lived there.

As a result, Covent Garden became an early example of conservation-led regeneration based on restoring existing buildings. Today, although the area has seen familiar high-street brands push out many small independent shops, the sense of human scale remains, with an absence of disorientating large office blocks or flats.

The cramped, busy market with its vegetable boxes piled unceremoniously beside the portico of St Paul’s Church, so atmospherically caught in Lindsay Anderson’s documentary Every Day Except Christmas (1957) and Alfred Hitchcock’s penultimate thriller Frenzy (1972), has gone. But the bustle remains, even if, as Peter Ackroyd writes in London, ‘the agile porters have turned into a different kind of street artist’.

Covent Garden has always been about small delights, not sweeping vistas, and that’s how we like it. Across nearly 500 years of history, as Prof Henry Higgins sang about Eliza Doolittle, we’ve grown accustomed to her face.

1552 The Crown grants the land to John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford

Covent Garden owes its name to the medieval market garden of the Benedictine Convent of St Peter’s, Westminster. Henry VIII took possession during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536, but, after he granted the land (roughly 40 acres bounded by the Strand to the south and High Holborn to the north) to John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, in 1552, the Earl simply let it out for pasture. In about 1588, Bedford House was built on sloping ground on the north side of the Strand, with a view of the Thames, as the home of the 3rd Earl, Edward, still a minor at the time.

1630 Francis Russell, 4th Earl, licensed to develop Covent Garden ‘with howses and buildings fit for the habitacions of Gentlemen and men of ability’

Inigo Jones was the scheme’s overall architect. The square was England’s first piazza and the arcaded properties on the north and east sides (none survive) were much admired. Early residents included Sir Peter Lely and the Civil War Royalist Sir Edward Verney, killed at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642. In 1638, St Paul’s Church, designed by Jones on an Etruscan model and London’s first new church since before the Reformation, was consecrated. Its sturdy, unpretentious exterior reflected Jones’s tongue-in-cheek vow to build ‘the handsomest barn in England’, to satisfy the cost-conscious 4th Earl. The portico is the setting for the opening scene of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. St Paul’s is in the heart of West End theatreland and has been dubbed ‘the actors’ church’: Ellen Terry is buried here and there are memorials to C. B. Cochran, Ivor Novello and Vivien Leigh. It was gutted by fire in 1795, but Thomas Hardwick rebuilt it to Jones’s design.

1706 Bedford House demolition facilitates the expansion of the market

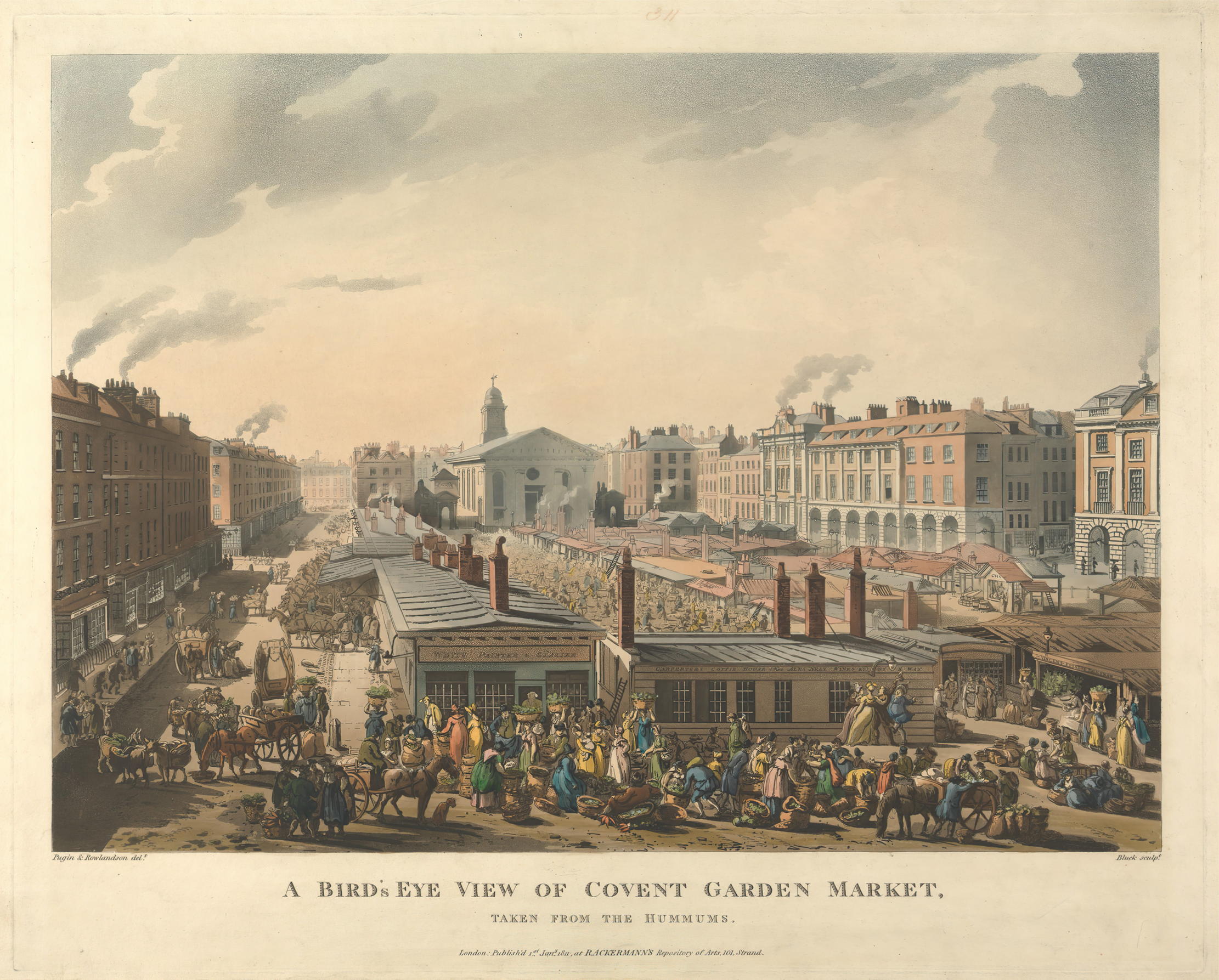

The Bedford House gardens bordered the south side of the piazza, where a market for selling fruit and vegetables was well established, the 5th Earl, William, having obtained a Royal Charter in 1670 after decades of unofficial trading. Bedford House’s demolition allowed further expansion, with the market stalls given permanent roofs. By 1800, Covent Garden was the largest vegetable, fruit and herb market in England.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The profile of the area had changed by then. As wealthier residents moved out, (the Bedfords to Southampton House, Bloomsbury, in the early 18th century, although they did not sell the Covent Garden estate until 1919), the arrival of coffee shops, taverns, boarding houses and Turkish baths changed a genteel atmosphere into a raffish one. At Button’s, on the south side of Russell Street, clientele included Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and Colley Cibber. James Boswell met Samuel Johnson in a parlour at the back of No 8.

1828 Building of the Central Market

This was an attempt to bring cohesion to the increasingly congested market. Gardener’s Magazine described Charles Fowler’s structure as ‘perfectly fitted for its various uses; of great architectural beauty and elegance; and so expressive of the purpose for which it was erected, that it cannot by any possibility be mistaken for anything else than what it is’. Later, a fine glass and iron roof was added by the builder William Cubitt. Subsequent market buildings included the Flower Market, Floral Hall and Charter Market. ‘Few places,’ observed a contemporary writer quoted in Bradshaw’s (1862), ‘surprise a stranger more than when he emerges suddenly from that great, crowded, and noisy thoroughfare, the Strand, and finds himself all at once in this little world of flowers.’

1847 Opera comes to Covent Garden

Covent Garden’s first theatre was the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which opened in 1663. Nell Gwyn appeared there, but it burnt down in 1672. The present building opened in 1812 and has witnessed performances by Edmund Kean, Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and Forbes Robertson, as well as the triumphant staging of Noël Coward’s Cavalcade in 1931. Opera came to Covent Garden in 1847, when the Covent Garden Theatre in Bow Street (originally opened in 1732, rebuilt by Robert Smirke in 1809), after a period of financial difficulty reopened as the Royal Italian Opera House in 1847. It was described as ‘decidedly the most splendid theatre in Europe’ by Bradshaw’s, destroyed by fire in 1856 and rebuilt within six months. Its architect, E. M. Barry, also built the Floral Hall next door, an unsuccessful effort to exploit the growing market for flowers. Opening in 1860, as Pevsner’s ‘Buildings of England’ notes, the hall was ‘the spirit of the Great Exhibition, tempered by intricate cast-iron decoration in the main members’.

1971 Public Inquiry held on plans for Covent Garden redevelopment

The inquiry felt the full force of local opposition to the destructive plans. As S. P. Plowden of the Covent Garden Community Association said: ‘Roads go in lines, character does not go in lines.’ Mercifully, the listing of 245 buildings in the area that same year made the plan unfeasible anyway. A Covent Garden Forum drawn from residents and local businesses was set up to play an active role in future policy making. Major changes included the restoration of the Central Market in 1980, now filled with shops and cafés, and the establishment of the London Transport Museum in the old Flower Market building.

2018 The Royal Opera House receives a facelift

There was controversy again in the late 1980s when plans to expand the Royal Opera House threatened the demolition of two of the oldest houses on Long Acre. Once again, tenacious locals helped ensure a more sensitive redevelopment was reached, with a refurbished Opera House reopening in 1999, and a reconstructed Floral Hall, now interconnecting with the Opera House complex. A further £50 million programme of works, completed in 2018, included the creation of a new glazed entrance and lobby on Bow Street and the enlargement of the entrance on the Covent Garden piazza.

2022 Covent Garden returns to its roots with urban farm

An initiative with Square Mile Farms to demonstrate Covent Garden’s commitment to sustainability was announced for a series of urban farm pop-ups on Floral Street. More than 120 herbs, salads and leafy greens were to be grown for local communities and charities. This was a continuation of sustainability efforts that have seen about 10,000 UK-grown plants dotted across the estate and in the piazza, as well as a vertical park landscaped on a building in James Street.

Somerset born, Sussex raised, with a view of the South Downs from his bedroom window, Jack's first freelance article was on the ailing West Pier for The Telegraph. It's been downhill ever since. Never seen without the Racing Post (print version, thank you), he's written for The Independent and The Guardian, as well as for the farming press. He's also your man if you need a line on Bill Haley, vintage rock and soul, ghosts or Lost London.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver

-

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwback

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwbackTactfully revived, Dennis Severs’ House defies categorisation, finds Jeremy Musson.

By Jeremy Musson

-

London's lost masterpieces: The palaces and Georgian gems torn down in 30 years of 20th century madness

London's lost masterpieces: The palaces and Georgian gems torn down in 30 years of 20th century madnessLondon would look very different had it not been for the widespread demolition of Georgian architecture in the 20th century. John Martin Robinson takes a look back at what was lost and what was fortunately saved.

By John Martin Robinson

-

The great houses of The Strand, 'London's Golden Mile' that 'helped shape England’s architectural identity’

The great houses of The Strand, 'London's Golden Mile' that 'helped shape England’s architectural identity’A scheme to pedestrianise parts of The Strand is throwing light on the road’s gilded history, finds Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

The best and worst of London's bridges, from the sheer elegance of Albert Bridge to the utilitarian solidity of Wandsworth

The best and worst of London's bridges, from the sheer elegance of Albert Bridge to the utilitarian solidity of WandsworthLondon's bridges are integral to an appreciation of the character of the city, as well as being great feats of architecture and engineering. Jack Watkins takes a look.

By Jack Watkins

-

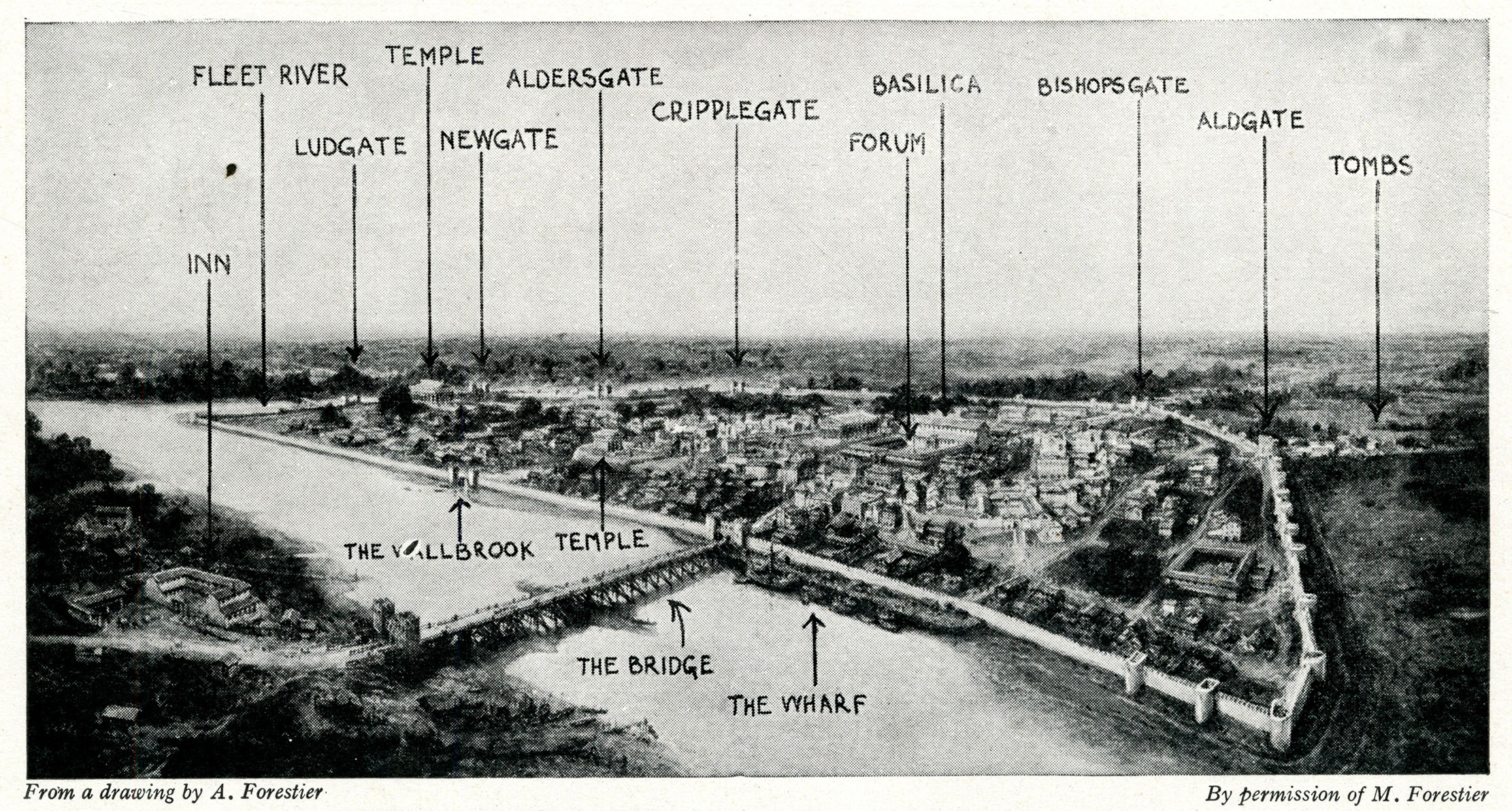

Oxford Street: How a Roman road evolved via public hangings into the most famous street of shops on the planet

Oxford Street: How a Roman road evolved via public hangings into the most famous street of shops on the planetTo coincide with the publication of a definitive new study of Britain’s most famous retail destination, Andrew Saint looks at the history of London’s Oxford Street.

By Country Life

-

The story of Old London Bridge, the iconic landmark which vanished from the capital's skyline

The story of Old London Bridge, the iconic landmark which vanished from the capital's skylineImportant new discoveries illuminate the form and history of the houses that lined one of London’s most celebrated lost landmarks. Dorian Gerhold explores the remarkable story of their construction and development.

By Country Life