The feudal splendour of Arundel Castle's magnificent interiors

Arundel Castle in West Sussex — the seat of the Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal — is every bit as spectacular within as it is from outside. John Martin Robinson describes the transformative representation of the Victorian interiors over the past three decades. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

In January 1923, Chips Channon, a young American socialite — later a Conservative MP — stayed at Arundel Castle. ‘An enormous party of over fifty here, mostly young, in celebration of Lady Rachel Howard’s “coming out”,’ he noted in his diary. ‘Arundel is so feudal and medieval (although much restored) that one expects beefeaters to bring in one’s tea. There are moats, battlements and portcullis… Somehow it has more atmosphere than Windsor, if less comfortable… A ball this evening in the great barons’ hall to which all the county came… we were over seventy at dinner and assembled in the… Gothic library-gallery and processed in state into the dining room. The castle itself is quite bare of interesting furniture and tapestry and only a few mediocre pictures.’

His account offers a fascinating vignette of how the large public rooms of the castle with their Georgian plan and Victorian architecture worked when en fête for special parties. What he says about the paucity of the contents, however, is surprising. The Barons’ Hall (Fig 2) would, of course, have been cleared for the dance and Channon presumably did not attend the Catholic services in the chapel, so he would have missed the rare quattrocento paintings and carvings there. His comment, however, underlines the degree to which the castle as it is decorated and arranged today — in common with other great houses such as Chatsworth in Derbyshire, Houghton in Norfolk, Wilton in Wiltshire or Grimsthorpe in Lincolnshire — owes its modern interiors to 20th-century revival and is much more magnificent and splendid than before the Second World War.

At Arundel today, the most important Georgian furniture and best paintings come from Norfolk House in London (demolished in 1938). These were only put on view in the castle after it was reopened to the public in 1947. There have also been subsequent influxes from other places, including Kinharvie, the Herries’ shooting lodge in Scotland, as well as many Georgian furnishings and decorative objects acquired specially from Malletts in the 1960s for the John Fowler interior of Arundel Park House (COUNTRY LIFE, June 20, 1996). Most of these came to the castle after the death of Lavinia, Duchess of Norfolk in 1995.

Previous articles in Country Life have recorded the history of the late-Georgian and late-Victorian reconstruction of the house around a quadrangle in the Norman south bailey and the 1990s restoration of the family apartment in the east wing. Last week’s piece examined the medieval history of this Arundel castle before its ruin in the Civil Wars of the 1640s. The purpose of the present article is to look at the ongoing restoration programme, with the revival since 2000 of the principal Victorian state rooms designed by Charles Alban Buckler for the 15th Duke of Norfolk between the 1870s and 1890s.

The successful integration and display of all the family collections, in tandem with fabric restoration that included re-leading the roofs, rewiring, and redecoration, has been achieved over the past decades by the present 18th Duke and the trustees. This follows the settlement of the castle by the will of the 16th Duke, who died in 1975, in an independent charitable trust to secure its permanent preservation. (The National Trust route was considered, but rejected as too sterile and bureaucratic.) The rooms have been transformed and brought to life over two decades, as shown in the photographs specially taken for this article.

The public route follows that enjoyed by visitors since the 19th century and begins with the chapel and Barons’ Hall, in the west wing, both distinguished exercises in mid-13th-century Gothic style. In the chapel (Fig 3), the stone has been part-cleaned and the original Victorian 1890s light fittings by Hardman of Birmingham restored and reused as part of the rewiring. They include Gothic wrought-iron standard lights, which were retrieved from the basement and reinstated. The new lighting enhances the sumptuous quality of the architecture, with its Purbeck marble, rich stone carving and Hardman stained glass.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the Barons’ Hall, the washing and conservation of the two large Gobelin ‘Nouvelle Indes’ tapestries high up on the end walls has brought out their colours and their arrangement has been improved by flanking full-length portraits continuing the series around the upper walls. Eight new wrought-iron Gothic electroliers based on designs by Buckler and made by a local blacksmith have been hung from the hammerbeams. The 16th-century Continental furniture collected for the room by the 15th Duke in the 1880s with the advice of Charles Davis, a Bond Street dealer, is now accompanied by rare objects from the same source, including a Japanese 17th-century lacquer shield and an ancient ivory crozier.

The gallery beyond the hall, added in 1708 to give access to the south-front rooms, extended in 1795 and remodelled by Buckler in the 1880s with a low stone vault, was rearranged in 1947 as a chronological picture gallery of ducal portraits, incorporating the ancestors from Norfolk House. This display has been retained and enhanced with new acquisitions, including a fine portrait of the 6th Duke by Hanneman bought in the 1960s, a portrait of Philip, 13th Earl of Arundel, attributed to George Gower (with the Lumley cartellino), and of Anne Dacre, Countess of Arundel as a widow, attributed to Mytens and acquired in 2007. All the pictures have been cleaned and were relit in 2022 with LED lighting.

Additional lighting has been introduced in the form of new wrought-iron standards copied from those by Buckler in the chapel. A feature of the Arundel interior is the Gothic Revival electric light fittings, the anachronistic design of which obviously amused Buckler and his patron the Duke, and the tradition has been continued in all the new electroliers. Classical busts on marble half columns originally here have been reinstated and help to ‘pace’ the long narrow gallery. They include a pair by François Dieussart (a pupil of Bernini) of Charles I and his nephew Prince Charles Louis of the Rhine commissioned by the 14th Earl of Arundel in 1636 and a series of the 13th Duke’s family of about 1840 by John Francis (a pupil of Chantrey).

Opening unexpectedly off the north side of the gallery is Buckler’s spectacular Grand Staircase (Fig 5), a symphony of fossil marble, heraldry and sculpture by Boulton of Cheltenham. Here hang the other two ‘Nouvelle Indes’ tapestries from the set of four bought by the 9th Duchess from the Gobelin factory in Paris in 1750 for the Great Room at Norfolk House at a cost of £9 a yard. They were cleaned, repaired, relined and rehung in 2020–22, to great effect. Also situated to the north is the Marshall Room, reconfigured as the billiard room (Fig 4) and conveniently next to the dining room for post-prandial games of Freda.

The billiard-cloth green of the walls was chosen by David Mlinaric, who also designed the green carpet runner. All the furniture re-assembled here, including the billiard table and the wrought-iron light fittings, was designed by Buckler. The walls are hung with a complete set of the Pine engravings of the Armada after the lost tapestries in the old House of Lords. They were bequeathed by Miss Elizabeth Rowell, who had spent a lifetime collecting them, having discovered the first in Lisbon in 1936 when her father was building the Portuguese Navy.

The principal state rooms are arranged en enfilade to the south of the gallery. The enormous dining room (Fig 1) is a Buckler evocation of the hall in the old Bishop’s Palace at Mayfield in West Sussex, the oak wainscot roof supported on stone arches and the walls punctuated by ecclesiastical lancets, which creates a light, airy space. It is on the site of the medieval castle chapel, which was converted into a dining room by the 11th Duke in about 1795. Four Gothic mahogany side tables survive from that phase, now complemented by a new Gothic display cabinet made from the old doorcase from the room, which migrated at the time of Buckler’s work to a house near Portsmouth. When that was demolished, it was retrieved and reused here.

The big drawing room (Fig 7) designed by Buckler in 1877 was completely redecorated in 2006, when the walls were painted moss green, the curtains replaced with Watts cut green velvet and two large new sofas made under the direction of Robert Kime, using handwoven, vegetable-dyed Asiatic textiles. The great feature of the room is the hang of eight full-length portraits, including two by Gainsborough and two by Reynolds. This has been adjusted and the two swagger portraits by Lely of the 6th Duke and his second wife, Jane, have been hung on the end wall at the suggestion of the late Sir Oliver Millar, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. Their scale, rich colour and Baroque design can be better appreciated there.

The Reynolds full length of George IV as Prince of Wales on his 21st birthday in Garter robes attended by a young black soldier from the Prince’s regiment of Hussars was at Norfolk House, then at Arundel Park, and can now be seen here in the castle for the first time. Another happy adjustment has been the reassemblage of the carved pier glasses with their matching brass side tables made originally for the Eating Room at Norfolk House, now brought together again as intended.

The ante library (Fig 9) was redecorated at the same time as the drawing room in 2006. As a space, this room bridges the transition from the Buckler rooms on the south front to the 11th Duke’s mahogany-lined Regency Gothic Library of 1802. The thin ribbed plaster ceiling and oak-leaved cornice dated from then, but the rich stone Perpendicular-style chimneypiece was inserted by Buckler.

Painted white after the war, the room had lost its Victorian decoration and the disparate bits looked incoherent. The ceiling has been grained oak by Hesp and Jones, echoing the oak wainscot of the drawing-room ceiling.

The walls have been stencilled by John Hesp in the ‘Norfolk Pattern’ (a Watts textile design), in crimson on a stone ground that gives a richer background for the important van Dyck portraits once hung at Norfolk House and now here. The effect is more like Pugin’s House of Lords than Buckler’s more austere, stone, Gothic in the Dining Room and Gallery.

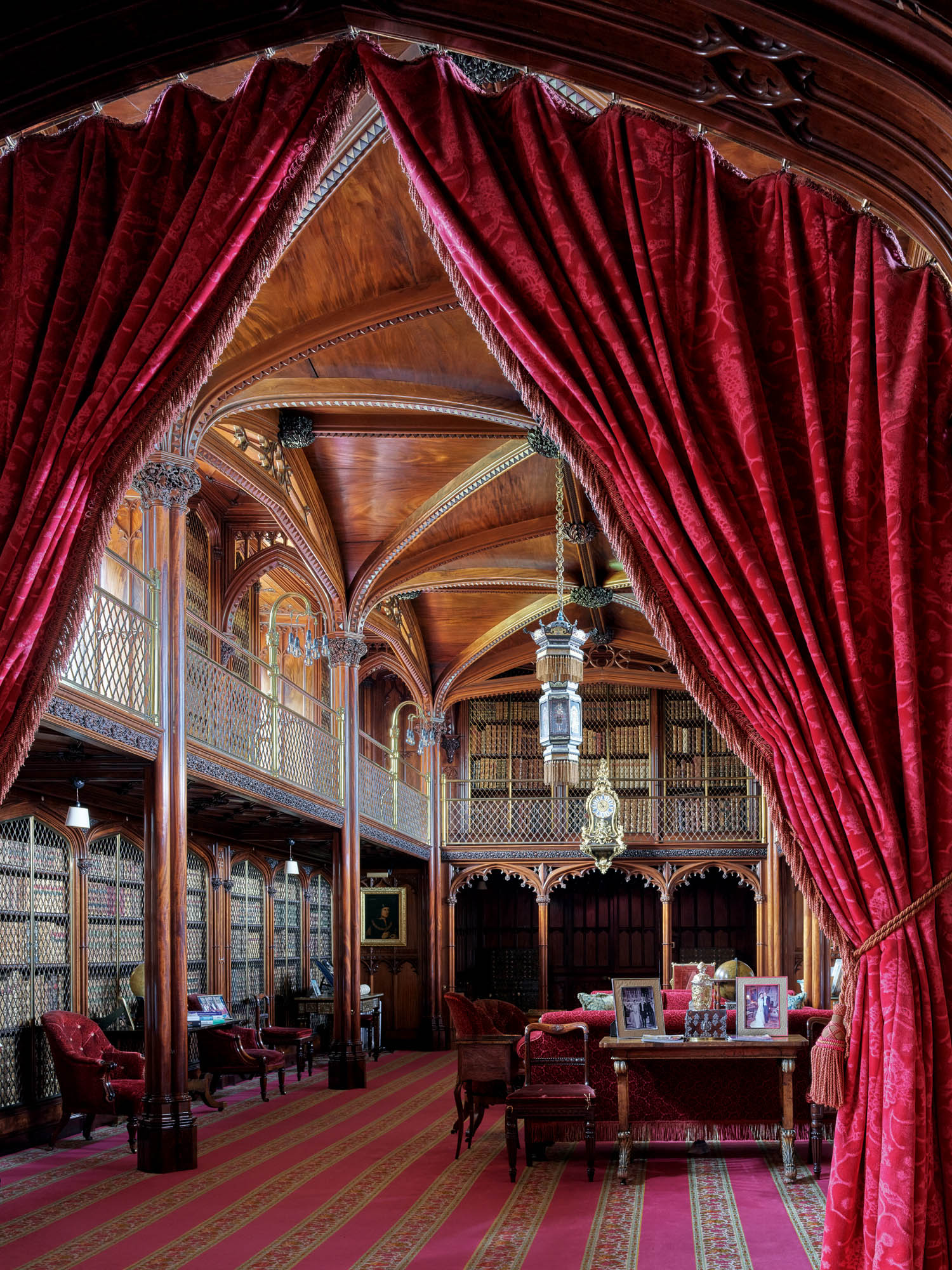

The state rooms culminate in the library (Fig 6), a gallery 122ft long that fills half the east wing. Designed by the 11th Duke himself and lined and ceiled in Honduran mahogany, which he bought wholesale in London Docks, it is finely carved by Jonathan Ritson, father and son, the Duke’s craftsmen-protégés from Cumberland.

A tour de force of Regency design, it was refurnished by George Morant, the fashionable Bond Street decorator, for Queen Victoria’s visit in 1846. Retained by the 15th Duke and Buckler as the best bit of the 11th Duke’s work and a perfect receptacle for the important Georgian collection of 10,500 books, it is a comfortable, as well as impressive interior.

It was the first of the major rooms to be redecorated and restored after 1987, under the direction of the late Clive Wainwright of the V&A Museum, when all the Morant furniture was reinstated from the attic, the carpet rewoven and Watts Norfolk Pattern stamped velvet curtains rehung at the central crossing. This scheme set the pattern for the full-scale revival of the other state rooms, which has continued down to the present day and the results of which can now be enjoyed by visitors to the castle.

Visit www.arundelcastle.org to find out more about visiting the castle.

The Library at Arundel Castle, the glorious centrepiece of one of Britain's most brilliantly restored buildings

Arundel Castle Gardens: 'Sometimes, a garden catches you unawares... the thought keeps recurring: I’ve never seen anything like this before.'

Tiffany Daneff visits Arundel Castle Gardens, sitting in the shadow of the castle and the cathedral at this beautiful West

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill