The chapel of Lincoln College, Oxford: 'Most costly and church-wise'

John Goodall describes the 17th-century expansion of Lincoln College, Oxford, to include an outstanding chapel, amid a bitter personal clash between two strong-willed men, and the institution’s evolution to the present day. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

This is part two of John Goodall's piece on Lincoln College, Oxford. Part I, about the foundation of Lincoln College, can be read here.

On September 9, 1603, the lawyer and diarist Sir Roger Wilbraham arrived in Oxford to find it afflicted by plague. It was busy nevertheless. The promised visit of James I to nearby Woodstock had brought the ambassadors of Spain and the Archduke of Austria to the city and they had taken up residence in Christ Church and Magdalen College respectively. On their architectural merits, Sir Roger judged these foundations, with Merton and All Souls’, to be the ‘four great colleges’ of the university. He was less impressed by the others, observing ‘Lincoln College and others I saw on the outside: they seem far inferior to the former’.

His reaction was not surprising given that Lincoln College — a relatively modest foundation, as we discovered last week — had hardly changed since its troubled foundation in the 15th century. Indeed, the events of the Reformation had by equal measure diminished and fossilised Oxford architecturally during the later 16th century. Sir Roger visited, however, at the start of a remarkable revival. As evidence of this, he admired the ongoing works to the city’s new library, the Bodleian, which he judged ‘for beauty of building… will equal any in Christendom’. Lincoln College, too, would be touched by this sea change in the university’s affairs.

The first college statutes of 1479, issued by Thomas Rotherham, Bishop of Lincoln, constituted a community of 12 fellows governed by a rector. Despite further small bequests into the 1530s, the college was rarely up to strength. During the Reformation, its fellowship was religiously conservative, but the institution survived and, from the 1560s, it began to accept numbers of paying undergraduates. To these were added fellow-commoners in 1606, ‘the sons of lords, knights, and gentlemen’ who ‘shall not go bow to Fellows in college’, but were to enjoy equality with them at ‘table, garden and other public places’.

To accommodate the expanding community, a two-storey range was begun in 1607, south of the original quadrangle along Turl Street. It comprised 12 chambers with attached studies. The new range followed closely in the form of its adjacent medieval predecessor, creating the long, low frontage seen by the modern visitor (although the battlements are a picturesque addition of 1824). Some of its interiors preserve wall paintings of landscape views. They were probably created in imitation of painted cloths, a common and cheap alternative to tapestry. A kinsman of the founder bishop and a former fellow, Sir Thomas Rotheram, shouldered the bulk of the expense for the new accommodation range. The following year, a cellar was also excavated under the hall buttery, presumably to increase the storage space available.

The new range was soon incorporated into a second quadrangle by another remarkable bequest, this time by John Williams, a Welsh-born churchman of driving ambition, bullish determination and Calvinist persuasion. According to his admiring chaplain and biographer, John Hacket, a childhood injury leaping from the walls of his native Conwy made him ‘chaste perforce’. He was educated at Cambridge, secured the favour of James I and cumulatively became — in quick succession in 1620–21 — Dean of Westminster, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal and Bishop of Lincoln.

At the same time, he fell out with the future Charles I, as well as his favourite the Duke of Buckingham and William Laud, from 1633 Archbishop of Canterbury and a reformer of Oxford University. What began as mutual distrust ripened from 1623 into deep animosity. This eventually proceeded to complex legal proceedings in Star Chamber and, in 1637, Williams briefly ended up imprisoned in the Tower of London and a popular hero. Williams delighted in tormenting Laud and was by character completely at odds with him; in his portraits, he appears more statesman than cleric.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Underpinning and reinforcing their personal divisions were, inevitably, disagreements over religious practice. Laud famously sought to dignify church services with beautiful fittings and ceremony, as well as to impose universal conformity of practice (with ultimately disastrous results). Williams’s views, by contrast, are much harder to characterise. As Dean of Westminster, he presided over some of the most extravagantly performed liturgy in the contemporary English church and, with Laud, vigorously defended the episcopacy. Yet he wrote a tract defending the alignment of the communion table east-west, as opposed to altar-wise, north-south, as well as — unusually for a Calvinist — apparently approving of railing it in for protection.

Therefore, although the decision taken at some point in the 1620s by Bishop Williams to build a splendid new chapel (Fig 3) at Lincoln College looks Laudian in character, it is impossible to read it straightforwardly as such. The same could be said of his wider patronage of learning. This included £2,000 towards the new library of his own college at St John’s, Cambridge (which at least one contemporary compared to Laud’s library at St Johns, Oxford); libraries in Westminster Abbey and his episcopal residences at Buckden, Cambridgeshire, and Lincoln; scholarships in Westminster School and even a bequest to a free school in Conwy.

In Hacket’s biography, the new Lincoln College chapel is described as ‘most elegant… costly, reverend and church-wise. The sacred acts and mysteries of our saviour, while he was on earth, neatly coloured in the glass windows. The traverse and lining of the walls was of cedarwood. The copes, the plate, the books, and all sorts of furniture for the holy table, rich and suitable’. One notable detail of this description is its reference to cedar, in fact only originally used on the screen (Fig 1) (the stalls are oak), but more familiar in opulent late-17th-century interiors. The chancel also has a chequered floor of white and black marble, a striking enrichment for the period.

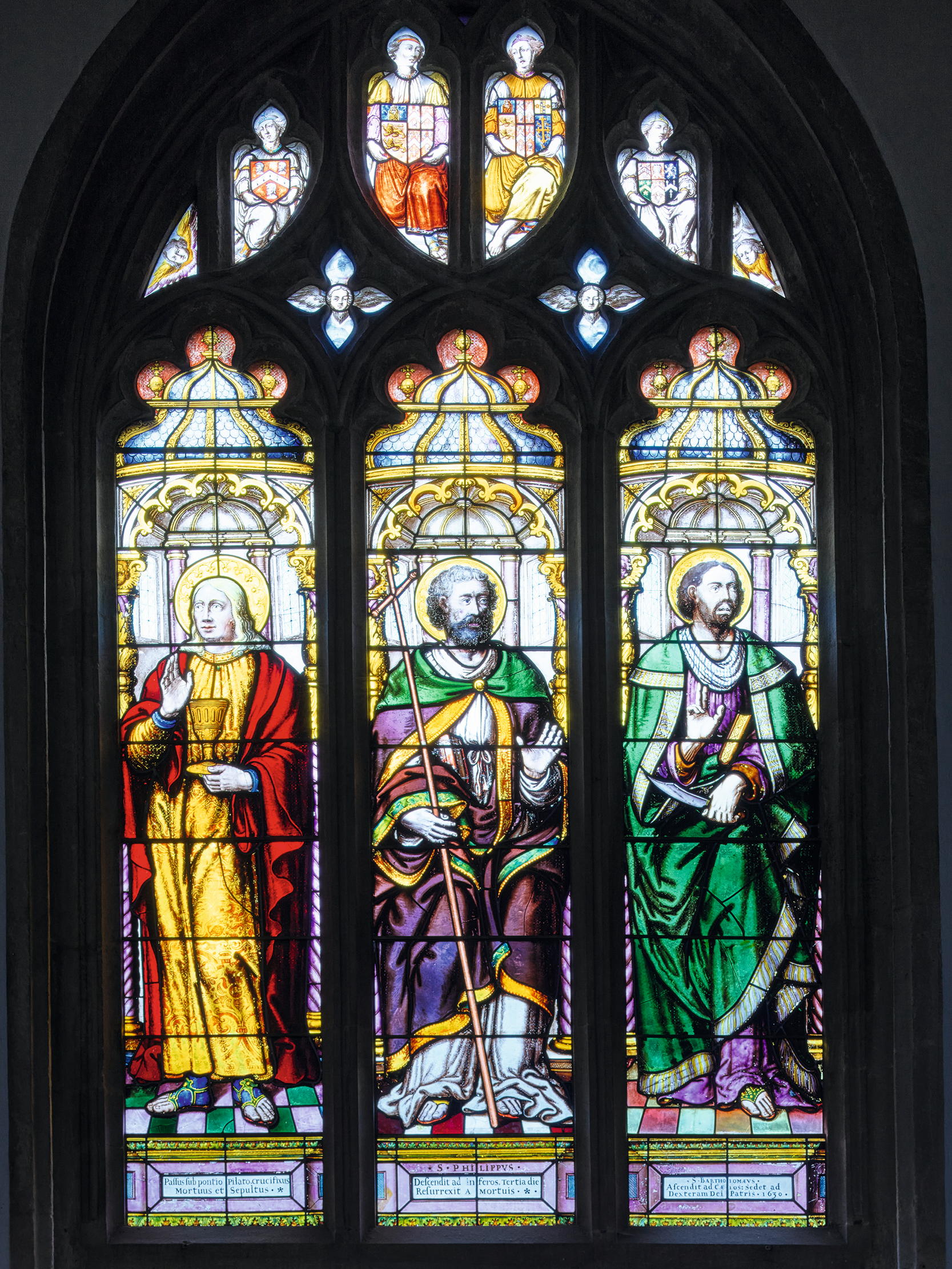

Even so, it is the stained glass that really catches the eye (Fig 2). This is coherently organised with full-length Old Testament prophets in the north-side windows facing Apostles to the south, the latter accompanied by sentences from the Creed. In each side window, the arms of Williams appear four times, combined, respectively, with the see of Lincoln, the College of Westminster and other branches of his family. The east window above the communion table is of six lights — an unusual number — giving equal emphasis to the episodes from the life of Christ and the Old Testament scenes that are understood to prefigure them; for example, the Resurrection with Jonah emerging from the whale.

Frustratingly, all the documentation regarding the chapel is lost, almost certainly in the course of Williams’s legal struggle with Laud. All we have to date the building are the inscriptions ‘1629’ and ‘1630’ in the windows. That said, the glass is initialled by the younger of two brothers, Bernard and Abraham van Linge, natives of Emden in East Friesland. The former contracted to create windows for Wadham College, Oxford, in 1621, immediately after his arrival in England, and his workshop was taken over by his brother after he returned home in 1623. That, in turn, probably identifies the mason involved here and the influences at play on the design.

Among many other projects, the van Linges worked on the glass of two chapels — that of Lincoln’s Inn, London, of 1618–22 and University College, Oxford, under construction from 1634 — in which the architectural detail of the building bears comparison to that at Lincoln College. The former project was overseen by the prominent Oxford mason John Clark and involved his brother-in-law, Hugh Davies; and the latter, after Clark’s death in 1624, Davies alone. Might Davies, therefore, be the figure responsible? Whatever the case, the glazing and architectural schemes seem to have been conceived together and, fascinatingly, show a particular awareness of the 14th-century architecture and iconography of New College Chapel, the most admired of Oxford’s college buildings.

Williams was mysteriously absent from the consecration ceremony of the chapel on September 15, 1631, which in the fractious context of the moment raises the question of who actually had control of it. In the published text, the beauty of the building is described with reference to the preached word. If the pulpit is not ‘sanctified’, it suggests, then the ‘purest things here shall be made unclean. This cedar shall not keep the savour… but shall smell of superstition. The altar shall be called no more than a dresser. The reverence that is done there shall be apish cringing, and all the seemly glazing be thought nothing but a little brittle superfluity…’. Is this Laudian jibing or Calvinist retort? Curiously, three months later, Williams consecrated another private chapel of a friend at Fawley Court, Buckinghamshire. It was destroyed in the 1640s, but might have offered further context for this splendid interior and the interpretation of the ceremony.

Since the completion of the chapel and its quadrangle, the architectural development of the college has largely involved renovation and also, more recently, the infill of the college landholding first constituted in the 15th century. The Civil War brutally interrupted the life of the university, but when Charles I assumed Oxford as his capital, Lincoln College became the home of his Exchequer. In the aftermath of the fighting and the upheavals of the Commonwealth, the college was returned to order by Nathaniel Crewe, later the Bishop of Durham and a noted philanthropist in his see.

Crewe’s father gave £220 for the conversion of the old chapel, which had remained disused since 1631, into a library. The work was undertaken between 1656 and 1662; the room is now the Senior Common Room (Fig 6). Long after he left the college, Crewe also contributed £100 to the renovation of the hall undertaken between 1697–1701. This was fitted with new wainscotting and a screen painted with his arms, as well as a fireplace to replace the original central hearth. In the interim, in 1686, a long-serving Rector, Fitzherbert Adams, paid more than £700 out of his own pocket for the renovation of the college buildings and chapel, creating the present ceiling with heraldic ornament, the front stalls and laying the marble floor in the nave. It was conceivably at this time that the entrance courtyard was first fitted with sash windows.

The 18th century did not witness much significant change to the college buildings or the scale of its community. In 1824, the exterior façade was battlemented and this enrichment was extended internally through the college quadrangles in 1854. More important changes followed from 1881, when Sir Thomas Jackson, also architect of the Examination Schools, refurnished the hall with a new Flamboyant Gothic fireplace and revealed the medieval open-timber roof from beneath a plaster ceiling. He added an extension, the Grove Building, to the rear of the hall, demolishing an 18th-century residential block.

In 1906, Herbert Read and R. F. MacDonald created an Edwardian Baroque library, now the Berrow Foundation Building, to which Stanton Williams added an award-winning extension in 2017. Read also built the unassuming Rector’s Lodging (Fig 5) in 1929–30, overlooking Turl Street. Shortly before this, in 1928, the American Methodist Committee paid for the creation of a museum room (Fig 4) to celebrate the 200th anniversary of John Wesley’s Fellowship at Lincoln College. The room, which was fitted out in an eclectic antique style, was then believed to be the one he had occupied. Further research suggests he actually lived in the chapel quadrangle.

Perhaps the most striking recent addition to the complex, however, is an Oxford landmark with a history of its own. All Saints Church (Fig 7) on the High Street was erected in 1706–10 following the collapse of the spire of its medieval predecessor. The authorship of this magnificent 18th-century church is debated, but Dean Aldrich, the arbiter of architectural taste in Augustan Oxford, certainly had a hand in its design. In 1971–75 it was made redundant and thoughtfully converted into a library (Fig 8) by Robert Potter. The conversion lends a happy symmetry to the story told in these articles: the church that was intended to be the spiritual home of Fleming’s college in 1427 now serves as the intellectual seat for its flourishing life in the 21st century.

Visit www.lincoln.ox.ac.uk

Acknowledgements: Louise Durning and Mark Kirby

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.