The buildings of Winchester College: 'An extraordinary tapestry of architecture and spaces'

Jeremy Musson offers an overview of the wealth of buildings created by Winchester College from the Reformation to the present. Photographs by Paul Highman for the Country Life Picture Library.

In architectural terms, Winchester College is perhaps chiefly celebrated for its outstanding core of late-14th-century buildings created by founder William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester. These are all buildings of rare significance — as discussed last week — and remarkable for remaining in continuous use for education for more than six centuries.

Their powerful presence, with courts and gates of stone and flint, have remained the core and anchor of the college as it has evolved. The story of the college’s later development, however, is no less fascinating or remarkable. This article looks at the buildings spread across its wider campus, which extends from the shadow of the Cathedral Close to the north, towards water meadows to the south and into the town to the west. Happily — and rather unusually for a working school — it's possible to visit Winchester College and enjoy many of its wonders in person.

As with so many historic institutions, Winchester College has undergone more radical transformation over time than is at first apparent. That change is illustrated both by alterations to the medieval structure, as well as the sequence of 19th- and early-20th-century academic buildings created to serve its changing needs. These include the work of some national figures, including William Butterfield, architect of Keble College, Oxford (Country Life, September 12, 2012) and All Saints’ Margaret Street, London W1; William White, prolific and inventive church architect; Basil Champneys, architect of Newnham College, Cambridge and W. D. Caröe, architect of No 1 Millbank in London SW1, now the House of Lords’s Offices. The latter played a significant, but discreet role in updating Chamber Court. Many of the architects who worked here were also involved in the school’s sister foundation, New College, Oxford.

READ MORE:

Through the labour of these, and others, over time, the wider college campus presents a veritable encyclopaedia of architectural styles and expressions, as well as evidence of changing responses to the past and the pressures of the present. Sometimes, this creates bold contrasts with the original buildings. Such is true, for example, with the alert red-brick presence of 1680s School (Fig 3) in the shadow of Cloister. More deliberately conforming in character is the early-19th-century flint-faced Tudor Gothic work of George Stanley Repton, including the stately Old Headmaster’s House of 1839–42. This is still home to the Head’s study and is soon to be occupied by the first woman Head since the foundation of the college, closely following the introduction of the first girl pupils in 2022.

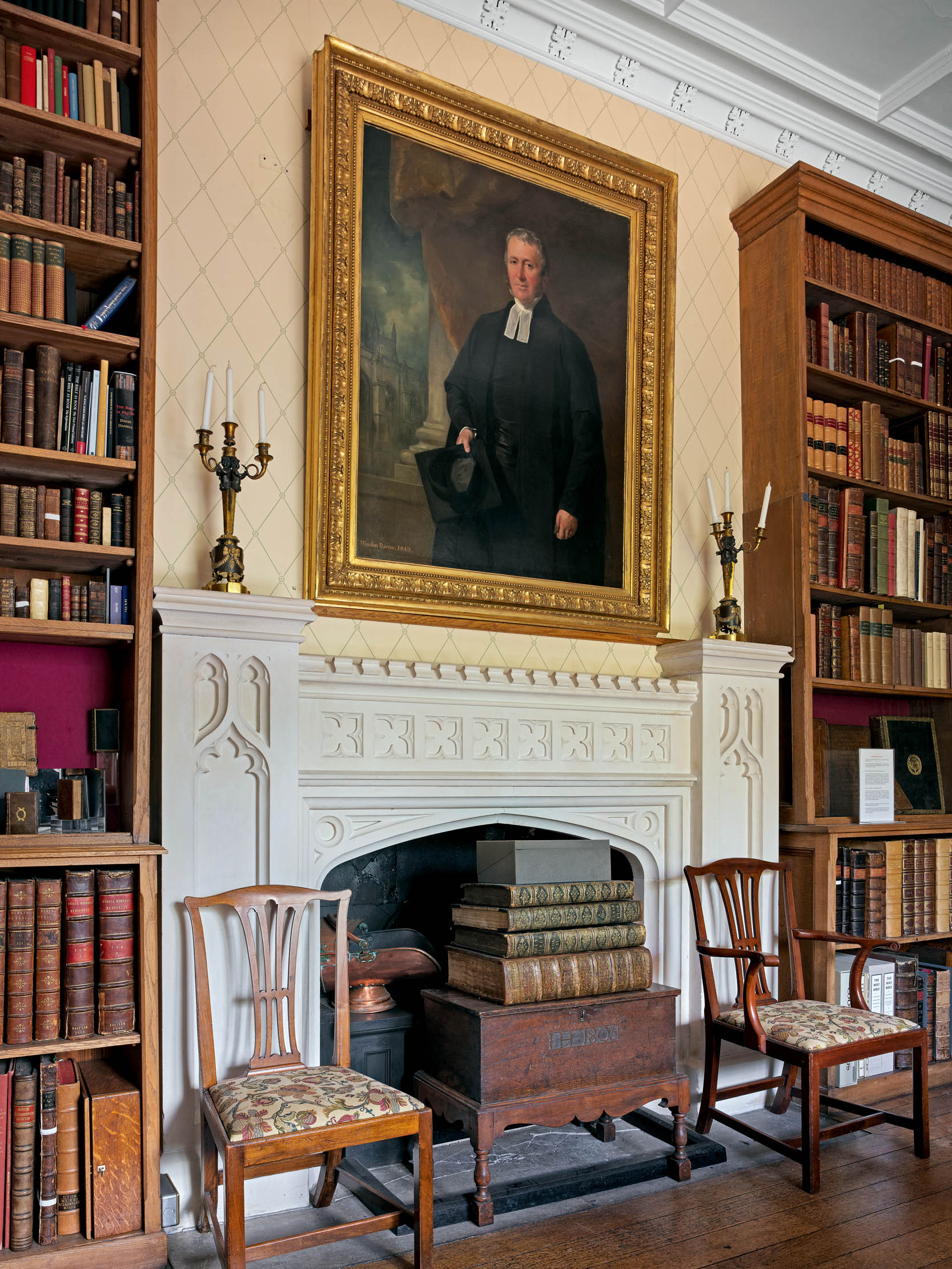

The expansion of the College began at least in the 16th century. The Warden’s Lodgings, in the chambers over Middle Gate, became inadequate for the Wardens, who could, after the Reformation, marry. Needing more living accommodation, they began to colonise the eastern end of Outer Court, extending their rooms first into and over the original granary. The process began with a Long Gallery — now the Fellows’ Library (Fig 2) — and then, in the 1590s, a Great Chamber, overlooking College Street. Changes for the scholars were much slower to follow; presumably, their living conditions remained relatively unaltered for the first two centuries of the existence of the college. The first sign of architectural change was the construction in 1656–57 of a gabled building of brick, a place of isolation for ill scholars in the age of plague, known either as Sick House or Bethesda, from the Hebrew for ‘a house of mercy’. For a long time, it stood alone, but it was gradually surrounded by new buildings in the 19th century.

In 1683–87, the huge single-volume building, known as School, was added immediately to the west of Cloister, in a warm red brick with round-headed windows, pouring light into the huge space inside. The building was once attributed to Sir Christopher Wren. More recently, on stylistic grounds, it has been given instead to Wren’s clever associate, Robert Hooke, architect of Ramsbury Manor, Wiltshire, as well as the Great Schoolroom of the Merchant Taylors’ School in the City of London. Yet another contender, however, is surely Edward Pearce, who was employed in the early 1680s to design the famous carved wainscot of Chapel, now displayed in New Hall.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The east-facing garden front of the Warden’s Lodgings was rebuilt in the early 1690s, before another addition was made in the 1730s along College Street linking the garden range to the Warden’s Study and Long Gallery. Thus, this elegant residence forms a complicated, but highly picturesque group, when viewed from the east, with classical brick elevations and sash windows flowing into stone. Good wainscot and joinery remain within.

From the 1730s, under headmaster John Burton, the remains of the Sustern Spital — or Sisters’ Hospital — just to the west of Chamber Court, were leased and extended to accommodate additional pupils, the non Scholars known as ‘Commoners’ and teachers. The heightened former hospital chapel became a house known as Wickham’s and a new range, known as Cloister Gallery, was built to connect it to a kitchen and dining room. Burton also built a substantial new headmaster’s residence that faced College Street to the north; all is recorded in engravings by drawing master Richard Baigent in 1838.

This jumble of buildings — ‘Old Commoners’ — was swept away and replaced from 1839 with a large-scale utilitarian, red-brick, U-shaped court to the south, forming the basis of the present-day Flint Court (originally known as ‘New Commoners’), designed by G. S. Repton (Fig 5) — son and architectural collaborator of the landscape architect Humphry Repton — who had trained in the office of John Nash. G. S. Repton also, in 1839–42, rebuilt the old Headmaster’s House with a flint and stone Perpendicular face to College Street, but with a conventional brick face behind. G. S. Repton had, a few years earlier, refaced and remodelled the part of the Warden’s Lodgings facing west into Outer Court (Fig 4) in a Gothic spirit, an interesting nod to the growing desire to stress the college’s antiquity, at the same time as providing up-to-date, if austere, facilities elsewhere.

As were many historic public schools, Winchester College was effectively re-founded in the late-Victorian period. Its transformation was overseen by George Ridding, headmaster from 1866 to 1883. It was at this time, at the height of the Gothic Revival in the 1860s, that Butterfield — then making such a splash with Keble College, Oxford — also carried out a major renovation at Winchester. In 1868–70, he adapted and tactfully Gothicised ‘New Commoners’ accommodation by Repton. His new fenestration artfully echoes the details of Chamber Court and subtly links buildings of different character. Slightly earlier, from 1862, he entirely rebuilt Chapel tower, but in its original form, following the failure of the foundations. He also meticulously recreated the 15th-century reredos above the high altar in 1874–75. The lower part of this was redesigned as a First World War memorial by Caröe, who otherwise transformed the interior of the chapel in the early 20th century.

Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the college expanded south of Flint Court by stages, with a military-looking Gymnasium (now the QEII theatre) and Rackets Courts (added by Butterfield from the early 1870s), the turreted and award-winning Sanatorium (now Art School) in a curious French Gothic in 1884–93 by White, and the ‘Memorial Building’, long known as Musa, short for the museum it contained, but also serving a time as Art School. This was built in 1894–97 to a design by Champneys.

The latter is a fine, Baroque-inspired design, well detailed, with the first-floor gallery room over a vaulted arcade and approached up a well-lit stone staircase (Fig 6). Correspondence shows how Champneys took pleasure in screening Butterfield’s muscular polychromatic gym behind. Beyond the enclosure of ‘Meads’ lies the extraordinary Science School (known as ‘Stinks’, after the smell of chemistry experiments), built in 1902–04 by Henry Hill of Chancellor and Hill, which has the disarming presence of a long Queen Anne country house looking over cricket fields to the river (later additions are on the road side).

‘Commoner Gate’, also known as the South Africa Gate, followed in 1902–03, designed by F. L. Pearson, son of J. L. Pearson, with whom he worked on Truro Cathedral in Cornwall. This provided a link to the many handsome and historic town houses of Kingsgate Street and College Street that the college gradually bought up from the late 19th century. Many of them are much older than their varied and handsome 18th-century façades suggest. One boarding house was created from a 17th-century house on Kingsgate Street, others became homes for teachers and their families. F. L. Pearson also designed the flint-faced Fives Courts that snake along Kingsgate Street south from Commoner Gate.

Commoner Gate now forms part of the approach to one of the most extraordinary of Winchester’s 20th-century buildings. War Cloister (Fig 1), built 1922–24 as a memorial to the fallen of the First World War, was designed by Sir Herbert Baker and passionately promoted by headmaster Montague Rendall. It must rank among Baker’s most sensitive and cerebral works of architecture and shows a strong Arts-and-Crafts consciousness. More than 500 names are inscribed in the panels of Hoptonwood stone on the walls, a chilling reminder of the losses of the First World War. Names of the Second World War fallen were added to the piers of the arcade.

War Cloister was first conceived as part of a series of new college buildings, providing useful modern spaces to the school. Baker even proposed the dismantling and re-erection of 1680s School on an alignment with War Cloister, eating up the gardens of Kingsgate Street. Perhaps the intention was to leave the medieval core of the college unencumbered. What Baker did achieve, however, was the sensitive and atmospheric conversion of the former college brewery, empty from 1904, into Moberly Library. It opened in 1934, an oak newel to the staircase carrying the memorable inscription ‘Minervae cedit Cervisia’; beer yields to wisdom.

The built estate of College extends beyond the core campus, but it would require another article to do justice to such structures as E. S. Prior’s Music School. In brief, there was a concerted campaign to expand the college in numbers, leading to new boarding houses, again to the west. From the late 1860s, four tall, imposing brick houses were built in generous garden plots between Kingsgate Street and St Cross Road — one, Sergeant’s, was designed by the leading Gothic Revival architect G. E. Street. This was all driven ahead by Ridding and his surveyor Thomas Stopher Snr. Other older houses were extended and adapted, the last new boarding house being completed in 1912, to designs by Charles Nicholson.

Not only the buildings, but the landscape setting of the college is exceptional. Meads, the walled-park area south of Chamber Court and School, was first added in the mid 16th century, when College acquired the former Carmelite Friary and St Elizabeth’s College, and the first enclosing wall was built in 1547 (to the south), using material from the dismantled St Elizabeth’s. For a time in the late 18th century, Meads was enclosed as a park for the Warden and Fellows. It was given over to boys’ use in 1790, but, until 1862, it was the exclusive preserve of Scholars and divided by a wall. Thereafter, it was shared with Commoners. The college’s recreational area was extended under Ridding, from 1870, with the draining of land south of Meads, to create New Field for playing fields. Beyond lies the heavily protected water meadows, the course of the River Itchen and the brooding green presence of St Catherine’s Hill.

Winchester remains a busy living institution. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that buildings and facilities have been added to and repurposed over time. One noteworthy recent initiative was the opening in 2016 of a new Treasury exhibition space within the former medieval stables, overseen by Radley House Partnership, with the contractor Moulding. Much else is under way, including a new sports centre by Design Engine, which is nearly complete, and significant new arrangements are being made for girl pupils, with two boarding houses designed by Stanton Williams.

The whole historic estate is an extraordinary tapestry of architecture and spaces, both institutional and residential, enclosed and open, private and public, polite and vernacular, ancient and modern. But each part is dependent on the consistency, weight, palette and texture of the other, governed by a sense of responsibility for the past and an openness to the opportunities of the future.

Winchester College: The school that's survived six centuries of turmoil, including the sacking of the city around it

Winchester College is both a school for the lucky few and an architectural marvel, says Clive Aslet.

Winchester College: A palace for education

John Goodall looks at the origins of Winchester College and the inspiration for its superb medieval buildings. Photographs by Paul

New College, Oxford: The 650-year story of the college that dreamt it was a palace

John Goodall looks at New College, Oxford, the most widely copied university college in England, a building inspired by a

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon