The architecture of the National Gallery, 'one of the defining landmarks of London'

In the wake of the re-opening of museums, John Goodall looks at the architecture of the National Gallery in London — with its interior photographed by Will Pryce for Country Life during lockdown.

From its commanding position above Trafalgar Square, the National Gallery is one of the defining landmarks of London. Curiously, the square, which was conceived by the architect John Nash as part of his planned redevelopment of the West End of London from 1813, just predates the institution. Nevertheless, the stories of both are inextricably linked.

Nash’s hugely ambitious proposals aimed to create a new processional way that would connect the garden suburb of Regent’s Park with Charing Cross, at the juncture of the Strand and Whitehall. In 1819, he suggested laying out a square at the termination of this route, clearing away the outer court of the Royal Mews that stood here and creating what he later described as ‘the finest site in London for a public building’.

The site Nash coveted was not — as the modern visitor might assume — the future site of the National Gallery. In 1819, this was the location of the most prominent of the Royal Mews buildings, the Great Mews, so called, designed by William Kent in 1731–32. Nor was it his intention to build a National Gallery; no such institution existed. Rather, he wanted to erect a Greek temple — modelled on the Parthenon — in the centre of the square, where Nelson’s Column now stands. It was to be a new home for the Royal Academy (RA).

Elsewhere in Europe, princely courts had naturally been centres of artistic patronage and, by the early 19th century, at cities such as Dresden and Berlin, their great collections were beginning to be formally housed and presented to visitors. In France, the Revolution and the ensuing centralisation of the state had created a collection at the Louvre in Paris that dwarfed comparison. Britain’s Hanoverian kings, by contrast, had no such collection to display and it was only through their connection with the RA that they performed a strikingly modest public, cultural role. That, incidentally, imposed very unusual dynamics on Britain’s artistic life in turn.

All this mattered because, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, Britain had unequivocally emerged as the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world. London, therefore, began consciously to assume the trappings of Imperial supremacy. The process harnessed government money (a fiercely contested source of funds), the hedonism of George IV and the enthusiasm of Britain’s wealthy merchant class. Cultural institutions were notable beneficiaries.

The collection of the British Museum, founded in 1753, started to grow exponentially (notably, with the government purchase of the Elgin Marbles) and, in 1822, work began on the leviathan new building for the institution designed by the architect Robert Smirke. Concurrently, the future architect of the National Gallery, William Wilkins, began work on University College London, the first university in the city.

Nash’s Parthenon was connected to this phenomenon. It celebrated the royal patronage of the Arts and implicitly proclaimed London to be a modern Athens. Indeed, it’s noteworthy that the new British Museum and London’s university were designed in a Greek idiom, a style that was both fashionable and imbued with this happy undertone.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Until 1824, the new RA was intended to stand in prominent isolation, but in that same year, after several failed attempts, a National Gallery came into existence: the government secured £60,000 to purchase the art collection of a wealthy merchant of Russian extraction, John Julius Angerstein, together with his house on Pall Mall. The building, which stood on the site of the Reform Club, was modestly improved as a gallery and opened its doors to the public on May 10. It immediately proved inadequate.

Also in 1824, the operations of the Royal Mews were transferred to new premises designed by Nash at Buckingham Palace, making possible the creation of his square. Two years later, in 1826, he presented more ambitious plans for the scheme. These now included a new home for the National Gallery on the site of the Great Mews behind his RA building. In addition, he proposed a new road connecting the square to the British Museum.

Nash’s plans never came to fruition in the end (although — confusingly — his colleague Smirke did realise one block of his proposed square in 1824–27, now Canada House). The trustees of the National Gallery, therefore, continued to lobby for better accommodation. Partly at their behest, various proposals were put forward from 1828 to create a new joint home for the RA and the National Gallery (as well as for the accommodation of public records) either re-using or replacing Kent’s Great Mews. In response, the government agonised over the costs involved.

The figure who broke the deadlock was Wilkins, who was also treasurer of the RA. He first commanded attention by promising to convert the Great Mews at the astonishingly low price of £33,000. Next, he asserted that he could build something wholly new on the site for a mere £41,000. The Treasury was sufficiently impressed by his cut-price offer to concede some visible enrichments, such as facing the building entirely in stone, rather than rendered brick. With the budget raised to £50,000, Parliament voted through the first instalment of the money on July 23, 1832. As completed, the building actually cost more than £81,000.

Wilkins’s design underwent various modifications, but, in its final form, it comprised a single range 460ft long and 50ft deep. A central entrance and stair provided access to new accommodation for the RA in the east wing and the National Gallery in the west.

That combined use partly explains Wilkins’s decision to create a relatively narrow, central entrance portico with disproportionately wide, spreading wings. The building was raised on a basement to give it height and the top-lit galleries of both institutions elevated onto the second floor, their position outwardly indicated by a register of blind windows.

Wilkins attempted to enliven this emphatically horizontal façade with a central dome and two subsidiary aedicules, a token concession to the Romantic delight in busy outlines that was now finding favour. In addition, he incorporated multiple changes of plane across the frontage. The most prominent is created by the projection of the central portico with its pediment.

This is flanked by two subsidiary porticos, originally the entrances to two passages cut through the frontage, one leading to a barracks behind the building and the other connecting to a street. Beyond these, like dying ripples on the surface of a pond, are two further façade projections that articulate the extremes of the wings.

The height and detailing of the building relate to those of the neighbouring church, St Martin-in-the-Fields. To make this much-loved building visible from Pall Mall, Wilkins was compelled by public demand not only to realign his new frontage, which was withdrawn 50ft from the square, but also to step it back at both ends.

In 1834, soon after construction had begun, Wilkins was offered some architectural and sculptural fragments to enrich the façade. Elements from the front portico of Carlton House, the Prince Regent’s nearby London home abandoned in 1822, were worked into the side porticos and panels of sculpture from Marble Arch were inserted across it. Disappointed at the effect, Wilkins had some of the latter removed and was reprimanded by the Treasury for the expense incurred.

In formal terms, Wilkins’s designs for this building bear striking resemblance to his earlier Greek Revival projects at Haileybury College, and University College London (which anticipated the central dome). It’s curious to note that, in the 1830s, Britain’s cultural interests moved decisively from the Antique to Renaissance Italy; a National Gallery of the 1840s would undoubtedly have been in the economic Florentine palazzo style pioneered from 1829 by the neighbouring Travellers Club.

The wings of Wilkins’s building were erected in advance of the central block. It was, therefore, before the central dome was completed, that the RA rooms were first used for the display of competition designs for the new Palace of Westminster, after the fire of 1834. Both institutions moved in and the National Gallery re-opened in its new premises on April 9, 1838. The same year, Hampton Court Palace also opened for free to the public.

By this date, Nash’s square had been named Trafalgar Square and, late that year, a competition was held to design Nelson’s Column. Two years later, Charles Barry (architect of the Travellers Club), created the terrace and steps that give presence to the National Gallery and help it dominate the square.

The new building was not well received. As early as 1844, there were proposals to enlarge the National Gallery’s exhibition space and, by 1848, in response to the quantity of acquisitions, calls for a completely new building. An architectural competition was subsequently held for this, but the decision of the RA in 1867 to move to Burlington House meant that the National Gallery could subsume its former apartments. Since that time, the gallery has been repeatedly enlarged, with incremental additions being added on coherent axes to the rear of Wilkins’s frontage.

This process of enlargement began in 1872–76, when E. M. Barry created a series of opulent galleries arranged around a central octagon behind the eastern half of the building. A decade later, in 1885–87, Sir John Taylor reconfigured the domed entrance hall and the line of galleries opening beyond it. This rear expansion of top-lit galleries continued westward into the 20th century, despite the creation of the off-shoot Tate Gallery for British Art in 1897.

By degrees, the interior decoration of the galleries became less strident in response to the taste for displaying things in neutral spaces. That approach was fully embraced in the North Extension, built in 1970–75 by James Ellis for the Department of the Environment. That neutrality was retrospectively imposed on the historic areas by cosmetic changes, such as the installation of false ceilings and the concealment of decoration.

A reversal of approach followed the celebrated controversies surrounding the extension of the gallery westwards beyond the line of Wilkins’s frontage in the 1980s. The winning design of a 1981 competition to redevelop this adjacent site was famously condemned by The Prince of Wales in 1984 as ‘a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much loved and elegant friend’. The comment launched the only modern national debate about architecture and style; not even the wave of high-rise building in London has done the same.

The eventual upshot of this intervention was the Sainsbury Wing of 1987–91, designed by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown. This incorporates the main entrance to the National Gallery today, as well as the great flight of stairs that is perhaps the defining modern interior of the building. The main galleries of the Sainsbury Wing — as opposed to its subterranean display spaces — are top-lit and strongly evocative in colour and treatment of such Florentine Renaissance buildings as the church of Santo Spirito. They also incorporate cleverly conceived vistas framing key pictures on what is in fact a slightly distorted plan. Externally, the wing makes playful reference to Wilkins’s frontage.

The Sainsbury Wing heralded the return of a delight in style to the architecture of the National Gallery. As part of that, the past 30 years has witnessed the gradual and welcome restoration of the historic decorative schemes in the building (most recently the Julia and Hans Rausing Room).

Another driving concern has been the management of visitors. Wilkins’s portico, still seemingly the main entrance, is problematic for modern access requirements with its many steps. It was partly to help the flow of visitors from Trafalgar Square that Annenberg Court was completed in 2004 by Dixon Jones. The competition to re-order the Sainsbury Wing announced early this year is also concerned with providing adequate access and facilities. For now, it’s hard to imagine a happier way of stepping out of lockdown than revisiting this free and superlative collection.

To book, telephone 020–7747 2885 or visit www.nationalgallery.org.uk

Best of British: 60 things that make Britain great

Our nation's greatest glories.

In Focus: The stunning collection of philanthropist Samuel Courtald, including Cézanne's most groundbreaking works

Courtald's collection of Impressionist works returns to The National Gallery for the first time in 70 years. Chloe-Jane Good takes

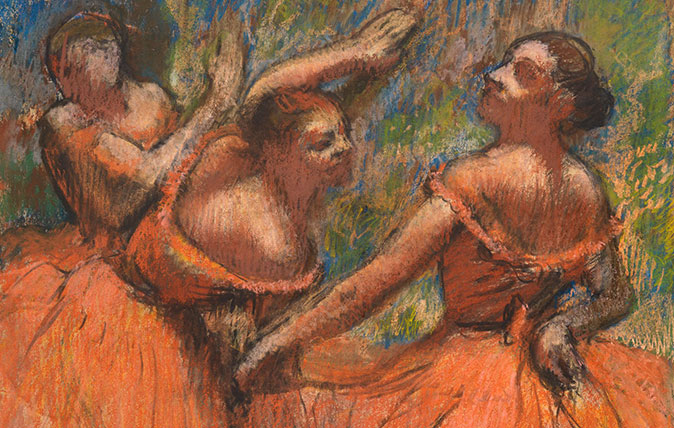

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.