Sudeley Castle: The tumultuous tale of one of the finest castles in the Cotswolds

John Goodall tells the story of Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire, and explains how a soldier — probably with the help of his mother — won the trust of a child king and created a great castle in the Cotswolds with the rewards. Photographs by Paul Highnam for the Country Life Picture Library.

John Goodall tells the story of Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire, and explains how a soldier — probably with the help of his mother — won the trust of a child king and created a great castle in the Cotswolds with the rewards. Photographs by Paul Highnam for the Country Life Picture Library.

At Westminster on May 5, 1458, Ralph Botiller, Lord Sudeley, a soldier and royal servant in his late sixties, was issued with a pardon for having fortified or battlemented two of his manors without royal permission.

One of these, The More, Hertfordshire, is now forgotten, but, in the 15th century, it was one of the grandest residences in the environs of London. Enlarged by a succession of powerful owners, it eventually came into the hands of Cardinal Wolsey and, in 1525, was judged by the French ambassador to be more magnificent than Hampton Court. The More fell into ruin during the reign of Elizabeth I and the site of it is now a field.

The other manor mentioned in the pardon was Sudeley, Gloucestershire, on the edge of the Cotswolds. This was Ralph’s family seat and the property from which he took his title.

The buildings he created here form the earliest parts of a castle that was likewise admired and extended by a sequence of powerful owners. It was archly described by the historian and divine Thomas Fuller in his posthumously published Worthies of England (1661) as ‘of subjects’ castles... the most handsome habitation, and of subjects’ habitations the strongest castle’. Whether Fuller actually saw the castle before its devastation in the Civil War is an open question.

Ralph’s pardon was issued in the febrile political atmosphere of the Wars of the Roses, but it was, in reality, no more than a matter of form. The Crown did not strictly regulate the erection of fortifications, but noticed the creation of castles as a matter of prestige. There were good reasons why Ralph had developed two buildings of such importance and chose to have them recognised in a royal pardon.

Ralph had begun his career in France in the service of the Duke of Bedford and, in 1419, combined good familial connections with London interests when he married Elizabeth Norbury, a widow of a mayor of London. The key to his later success in royal service, however, was his link to Henry VI, who acceded to the throne in 1421 at nine months old.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In January 1423, Ralph was appointed to the governing council of the realm and, in February the following year, his mother, Dame Alice, was appointed governess of the King with responsibility for his courtoisie et nourture, with permission to ‘chastise him from time to time’ and with guarantee of safety from reprisal in time to come for doing so. As a matter of fact, she later received presents from her former charge.

His mother’s appointment can’t have been a disadvantage for Ralph, who served in the King’s inner household and — despite the disparity of age — likewise won his affection. He became a chamber knight in 1430, attended Henry VI at his Coronation in Paris in 1431 and was appointed chief butler in 1435.

By the time the King came of age in 1437, Ralph had further allied himself with the circle of the King’s favourite, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1440 and Chamberlain of the Royal Household in 1441.

Soon after this last appointment, Ralph was created Lord Sudeley, on September 10, 1441 — the first title bestowed by Henry VI. It was issued by the unusual means of royal patent, probably because his mother was still living and remained in possession of the family seat at Sudeley. It was only when she died in 1443, the same year he became Treasurer, that he took full control of his patrimony.

Ralph’s offices brought with them an enormous collective revenue and Treasurers, in particular, often built on a grand scale. Ralph was no exception and he probably built Sudeley in the 15 years between 1443 and his pardon. In the 1540s, the visiting antiquarian John Leland was told the castle was built from the spoils of the French wars and that one of its towers — Potmare’s Tower — was named after a ransomed prisoner. It’s a strange name for a French aristocrat (even allowing for corruption), however, and the same source also told Leland — quite inaccurately — that Ralph was an admiral. That he was enriched by war is likely, but it was probably his offices that really gave him the means to build.

A castle is documented at Sudeley (or nearby Winchcombe) from at least the 12th century, but it’s likely that Ralph’s building occupied a virgin site. In its present form, it is laid out around two courtyards on a figure-of-eight plan. Many of the existing buildings post-date Ralph’s ownership, but there are sufficient vestiges identifiable by such technical details as shared mason’s marks to suggest that he established this plan.

The most important domestic interiors were in the southern court, which is dominated by one tower of exceptional scale at the north-west angle of the plan. As befits a castle tower, it is austerely detailed and constructed of cut blocks of stone . Its windows are not arched, but rectangular, a treatment introduced to England in the 1430s in fashion-able brick architecture. The tower rooms were comfortably appointed domestic spaces with latrines and fireplaces. In the range attached to the tower were the castle kitchens.

There were two other smaller towers to either side of the castle at the juncture of the two courtyards, one of which accommodated a bank of latrines. The likelihood is that the hall of the castle ran between them so as to divide the two courtyards. All trace of this is lost, however, and some modern authorities have suggested that the hall stood in the shadow of the principal tower. A few fragments of 15th-century buildings remain in the outer court, notably the gatehouse.

There were also buildings in the environs of the castle, as was often the case with large residences in the 15th century. To the west are the ruins of a large barn and, to the east, a freestanding chapel. The latter had small chambers to the north and south, only one of which survives. These were almost certainly closets, rooms from which Ralph and his family could practise their devotions in private, overlooking the altar.

To a visitor in the 15th century, the castle would have seemed connected to the neighbouring town of Winchcombe and the great Benedictine abbey that dominated it. Winchcombe Abbey was the burial place of Ralph’s ancestors and the church is one of the major lost medieval buildings of the Cotswolds. It’s likely that abbey and castle shared a common master mason and Ralph certainly contributed money to the parish church, which was jointly patronised by the abbot.

Ralph was too old to play an important role in the Wars of the Roses from 1459 and, having outlived his heir and evidently under pressure, presented the castle to the Crown. He played an unhappy role in the attempted restoration of Henry VI in 1471. According to The Great Chronicle of London, he paraded the King in a blue gown through the City in a fashion ‘more like a play than the showing of a prince to win men’s hearts’. He was imprisoned for his trouble and died in 1473.

Meanwhile, at Sudeley, there followed a rapid and confusing sequence of ownership. In 1469, Edward IV granted Sudeley to his 16-year-old brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III). Within a decade, however, Richard returned Sudeley to the Crown in exchange for the Honour of Richmond, Yorkshire. Then, as King from 1483, he resumed control of the castle, only famously to lose it with the throne two years later at the Battle of Bosworth.

The new King, Henry VII, granted Sudeley to his trusted uncle, Jasper Tudor, whom he created Duke of Bedford. Jasper controlled a vast triangle of territory extending from Wales through the Midlands. When he died in 1495, the castle reverted again to the Crown and was surveyed. Either Richard or Jasper (tradition favours the former, but there is no documentation either way) added a sumptuous new chamber block to the castle.

Two walls of this exceptionally sophisticated building survive. They show that the interior comprised a pair of richly appointed chambers at ground- and first-floor level, probably a parlour and great chamber above. The latter had walls with a blank lower register for the hanging of tapestries, the most valuable of all wall coverings. It was also completely encircled by windows, the largest splendidly detailed with miniature vaults and carving.

By an ingenious sleight of hand, the fireplace appeared to have no chimney. The flat ceiling was supported on the backs of angels and, for those who wanted to enjoy the air, a stair in one corner connected the room both with the garden below and the leads of the roof.

An interior of this kind — boxy in proportion and with grids of windows — anticipates much later Tudor interiors, such as the hall at Forde, Dorset, or the Guard Chamber at Hampton Court Palace and even Jacobean buildings. It’s an implicit mark of admiration that no subsequent occupant of the castle modernised the great chamber, although fixing sockets show that the lower register was later wainscoted with a dense (and correspondingly expensive) grid of panelling.

During his visit to Sudelely in the 1540s, Leland particularly marvelled at the glazing of the castle hall with ‘rownd beralls’. Leland would have associated beryl with lenses and the implication, therefore, is that the glass was exceptionally clear. It’s quite obvious that an interest in brilliant light particularly underlies the great chamber; perhaps the hall was rebuilt at the same time as the chamber block and both were similarly glazed.

At the death of Henry VIII, the castle became a trophy in Court politics and was granted to Thomas Seymour, brother of the Lord Protector, the Duke of Somerset. He was created Baron Seymour of Sudeley, appointed a Knight of the Garter and married Henry VIII’s last wife, Catherine Parr. She was later buried in the castle in 1548, with Lady Jane Grey as chief mourner. Thomas aspired to the hand of the Princess Elizabeth, but, in 1549, was executed for his ambitions, his death warrant signed by his brother.

The castle next passed to the soldier John Brydges, who had previously been constable of Sudelely in 1538–42. It was granted to him by Mary I, soon after he supported her triumphant entrance into London to claim the throne after the death of Edward VI in 1553. The following year, he was created Baron Chandos and granted reversion of the lands of Winchcombe Abbey, making him a major landholder in Gloucestershire.

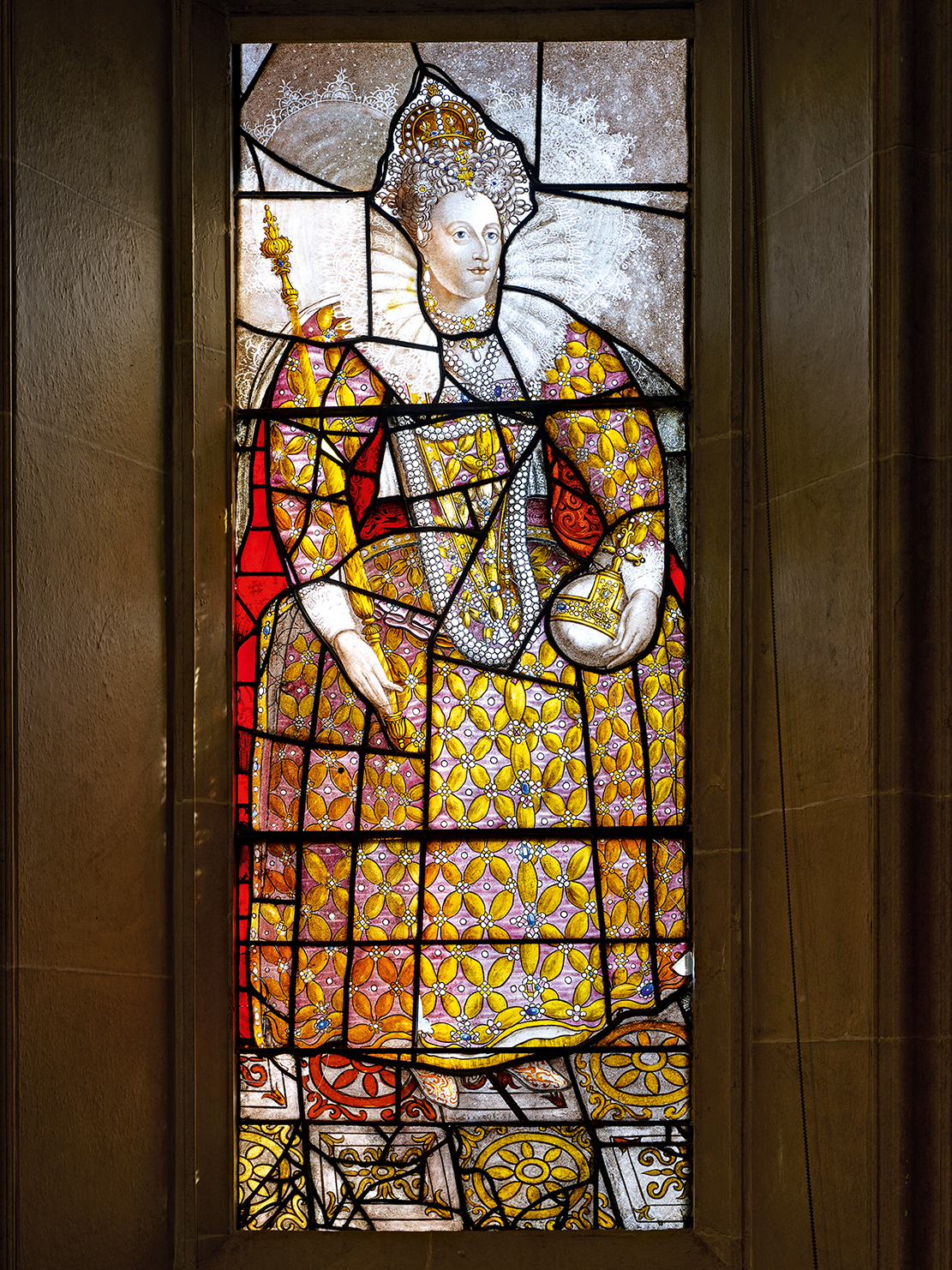

Edmund Brydges inherited his father’s land and titles in 1557. He was appointed to the Order of the Garter in 1572 and it was probably in celebration of this dignity that he modernised the castle with the advice of William Spicer, a mason concurrently active in the redevelopment of Kenilworth, Warwickshire, for the Earl of Leicester. Spicer’s work seems to have involved the regularisation of the outer court and its gate and includes a signature technical mannerism: triple angles at the corners of buildings. Edmund’s eldest son, Giles, received Elizabeth I at the castle three times between 1576 and 1592.

There is evidence of further adaptations to the castle in the early 17th century, but it is hard to judge their extent because the buildings suffered a devastating Civil War. Sudeley was surrendered to Parliament and recaptured by Prince Rupert in January 1643, sacked in June 1644, garrisoned in 1645-49 and finally slighted at the expense of its cavalier owner, George, 6th Baron Chandos.

When he died in 1655, he was buried in the chapel, but the castle was a ruin. It was not forgotten, however, and in later years it was unexpectedly revived both as a country house and as a theatre of English history — and that’s a story that we’ll tell in a future week.

Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire, is the home of Elizabeth, Lady Ashcombe, and the Dent-Brocklehurst family. It has partly re-opened to visitors and is open daily. Booking is essential — www.sudeleycastle.co.uk

Credit: Strutt & Parker - re-use fine

A rare and wonderful estate that includes a Georgian house, a former royal deer park and 500 acres of the Cotswolds

Sudeley Lodge Estate, one of the most remarkable properties in Gloucestershire, has come to the market.

The country house kitchen created from six knocked-together rooms to create a stunning 1,000sq ft living, cooking and entertaining space

Country Life's inaugural award for the creation of a new kitchen in an old space has been awarded to Birdsall

Credit: Alamy

Best places to live near Bristol – and what you could get for your money

Commuters working in Bristol and looking to live in the country have all sorts of fantastic options, with places that

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published