Stirling Castle: Renaissance of a Royal Palace

It was within sight of Stirling Castle that two of the most famous Scottish victories over the English were won. John Goodall takes a look at this impressive building and its history; all photographs by Paul Barker for the Country Life Picture Library.

Every Tuesday we look at an article from Country Life's architecture archive. Today, it's a 2011 piece on Stirling Castle by John Goodall, currently our architecture editor.

Set dramatically on an outcrop of rock above the floodplain of the River Forth, Stirling Castle commands a natural crossroads between the Highlands and the lowlands of Scotland. The castle enjoys a central place in the Scottish historic consciousness, and in reflection of its importance has been the object of one of the most ambitious recent projects of restoration and representation of a historic building in Britain. Running over a period of 20 years, the last stage was completed earlier this year, and the castle was officially reopened by The Queen in early July.

A castle existed at Stirling by the 12th century and served from the first as an important royal residence. It played a prominent role in the Scottish Wars of Independence and it was within sight of the walls that two famous Scottish victories were won: the defeat of Edward I's army at Stirling Bridge in 1297 and the humiliating rout in 1314 of Edward II's larger and better equipped force at Bannockburn. In the aftermath of the latter battle, Robert Bruce demolished the castle to prevent its reoccupation by the English. It was quickly refortified, however, and from the late 15th century, Stirling was rebuilt by the Stuart kings.

Fig 1. The forework built by James IV. Behind it rises the royal apartments of about 1538. These cannibalised a group of earlier buildings.

The process was initiated by James IV, who erected a splendid new symmetrical façade to the castle, with towers and a gatehouse, known as the forework (Fig 1). In addition, he built a new hall and a group of royal apartments. The full extent and dating of much of this work is uncertain, but the forework was completed by 1506 and the hall in about 1503, when the interior was being plastered. In conjunction with these changes, he endowed the college in the castle by 1501.

James IV was killed at Flodden in 1513 and it is conceivable that his work at Stirling was incomplete at the time. If so, it might explain why his son, after coming of age and taking his second wife, Mary of Guise, created a residential courtyard in the castle on a very grand scale. Secure dates, again, are strikingly thin on the ground, but the operation probably began in 1538. Recent archaeological analysis has shown that the earlier buildings were refaced and internally regularised to create two suites of chambers for the king and queen around a central courtyard. Tree-ring dating shows that the timbers of the surviving roofs were felled in the 1530s.

Fig 2. Perhaps the most successful interior is the richly furnished queen's bedchamber. The canopy of estate is placed over the fire in the French fashion.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

To aggrandise the exterior of this courtyard, its three principal faces were boldly ornamented in a fashion that is hard precisely to parallel. A French source has been suggested for this design, although any mason trained in the highly sophisticated and - relative to Scotland - vastly resourced architectural operations of Francis I would surely have goggled in bewilderment. One possibility is that the building was realised by a Scottish mason from a French drawing. Alternatively, that it is cosmetically French, with Renaissance detail marshalled on the façade in conformity to the medieval expectation that a lavish work of architecture should be bedecked with a maximum of sculpture.

James V died in 1542, leaving his infant daughter Mary Queen of Scots to succeed him. She was crowned in the castle chapel that her son, James VI, rebuilt on a slightly different site in 1594 for the baptism of his eldest child, Henry. After the union of the crowns in 1603, the Stuarts effectively abandoned the castle as a residence, although a fine series of surviving paintings was executed in the castle chapel in 1628-29 before a visit by Charles I.

Fig 3. The triptych in the queen's bedchamber painted by Owen Davison.

Growing concerns about the government of Scotland in the 18th century brought about a further transformation of the castle as a military base. It is from this period that the first detailed information about the buildings survives, notably surveys of 1709 and 1719. In this period, the hall was internally divided and converted into a barracks, and a lodging for the governor was created within the attic of the royal apartments. Then, in 1777, a celebrated series of fine 16th-century roundels was removed from one or more ceilings in the building and distributed as curiosities. Jane Graham, the wife of one governor of the castle, drew and later published the entire sequence. By the late 19th century, the main rooms had been heavily adapted for the use of officers.

The army finally marched out of Stirling Castle in 1964, and it was fully opened as a historic monument. In 1991, its present guardian, Historic Scotland, proposed a programme of works that would embrace the conservation of the fabric and allow for its re-presentation to the public. What you see today is the culmination of this ambitious programme following the investment of £21 million by the Scottish government.

Fig 4. Four of the reproduction heads from the king's inner hall.

Two changes have had an enormous impact on the physical appearance of the buildings. The first was the restoration of James IV's great hall. In 1965, some work had been done to tidy up this building and clear it of military partitions. It was now proposed to return the hall to its appearance at about 1500. This involved the removal of later fenestration, the rebuilding of the battlements, the reopening the original windows, and the re-creation of the lost open-timber roof and screens passage.

Curiously, such a sweeping operation would be unlikely to receive official sanction today under heritage-protection laws, but there is no arguing with the impact of the final result (Fig 5). In particular, the roof - its design informed by surviving parallels (notably that of the hall at Edinburgh Castle), and a 1719 survey drawing-is a staggering creation. All the oak has come from Scottish coppices. As a final touch, the hall exterior (Fig 6) has been surmounted by heraldic beasts and limewashed - as it originally was - and, in the sunlight, is now visible from miles away.

Fig 5. The restored great hall.

Work to the hall was completed in time for the millennium and attention shifted to James V's apartments, which it was likewise proposed to re-create in their completed form of about 1542. Again, the project, headed by the architect Peter Buchanan, was founded on a thorough archaeological and historical investigation of the building. This has revealed that the courtyard cannibalises and regularises a group of earlier buildings. Rather disappointingly, however, the only surviving evidence of a 16th-century decorative scheme it identified is a smut of red paint on one of the fireplaces.

To inform the re-creations of the different rooms, a research project was initiated in partnership with Glasgow University. This looked at the comparative European evidence for palace furnishings and decoration in the 1540s. Based on this work, new furniture has been commissioned for the rooms - created by Ken Peterkin of Arttus Period Interiors - as well as wall hangings (Fig 2) and even a reproduction altar retable for the queen's bedchamber, depicting her patron saints (Fig 3). The walls and ceilings of all the interiors have also been repainted with historically derived schemes by John Nevin and Graciela Ainsworth (Figs 7 and 9).

Fig 6. The great hall has been strikingly limewashed and its parapets restored with heraldic beasts, battlements and turrets.

An early decision was taken to re-create tapestries for the interior. As no surviving tapestries from James V's collection have been identified, it was decided to re-create a set of the right period. The choice fell on the Unicorn Tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and a private sponsor was found to underwrite the lion's share of the production cost of £2 million. The tapestries have been woven by West Dean College Tapestry Studio, led by Carron Penney, at reduced scale and the set is nearly complete (Fig 8).

Work also began to create copies of the Stirling heads, the one securely identified decorative survival from the palace (Fig 4). Over five years, the carver John Donaldson has created an outstanding series of 37 replicas, plus one invented head incorporating a portrait of his daughter. Intriguingly, tree-ring dating of the heads demonstrates the set is made from Polish oaks felled in the 1530s.

Fig 7. The queen's inner hall is hung with reproductions of the Hunt of the Unicorn Tapestries. All have been reduced in size by 10% and hung high for protection.

It has proved impossible to determine conclusively how the heads were first mounted and configured. Part of the problem lies in establishing how many there originally were. Inconsistencies in the border decoration of some roundels may suggest that some of the surviving carvings include the remains of more than one original. If so, the scheme must have extended over at least two rooms.

Nevertheless, the presumption has been that the heads formed part of a coherent iconographic programme underlining the virtues of James V's rule and his dynastic pretensions. Consequently, they have been grouped in the ceiling of the King's Inner Hall according to their supposed subject matter, which has been identified by comparing them with contemporary works, particularly prints. They include a group of royal portraits, images of the Nine Worthies and of Hercules.

Fig 8. The queen's outer hall. All its painted decoration is inspired by 1560s work at Kinneil, near Bo'ness, Stirlingshire.

In recent years, there have been several attempts to re-create historic interiors, notably at Dover Castle (COUNTRY LIFE, March 24, 2010). Stirling is surely the grandest of these projects to date, outstanding by virtue of its long planning, research and ambition. Visitors will undoubtedly be very impressed by what they see and also beguiled by the research and craftsmanship that underlies every fitting and detail. And rightly so. They may also enjoy the presence of costumed interpreters, who are intended to animate the interiors.

For all there is to celebrate in this creation, however, it is important not to lose sight of the tensions here. The fundamental justification for an enterprise of this kind is that it makes historic places more comprehensible and attractive to visitors by making them seem like real and living spaces. For those involved in creating them, moreover, they afford an invaluable opportunity for what might be called experimental research and craftsmanship.

Fig 9. A view of the King's Bedchamber: The interiors are presented as they might have appeared in the mid 16th-century, after the death of James V in 1542 (he may never have actually seen them complete). As a result, the king's apartments are not dressed. Here, the bed frame is shown without clothes, and no tapestries are hung on the walls. The fireplace overmantles in all the rooms have been painted with heraldic motifs on advice from the Court of the Lord Lyon to designs by Romilly Squire. No painted decoration has been applied to the surviving fireplaces, although they probably were coloured originally.

In the absence of identifying inscriptions, this presentation cannot be viewed uncritically: it supposes a visual literacy on the part of a 16th-century onlooker sufficient to identify the subject of the individual heads by reference to their artistic sources. To my mind, this seems over-optimistic.

Nevertheless, what has been created is a historicist interior shaped by modern sensibilities and perceptions. Indeed, the scholarship of this project aside, the unusual willingness of politicians to pay for this project is surely bound up with a desire to emphasise the historical credentials of Scotland's claims to independence on the European stage. The representation of Stirling may or may not successfully take us back to the 16th century, but it certainly immerses us in the 21st.

Voewood, the 'supreme example' of a butterfly-plan house in Norfolk's beloved Poppyland

Country Life's Mary Miers praised the eccentricities of the Arts-and-Crafts style in a piece from our archives published in 2009,

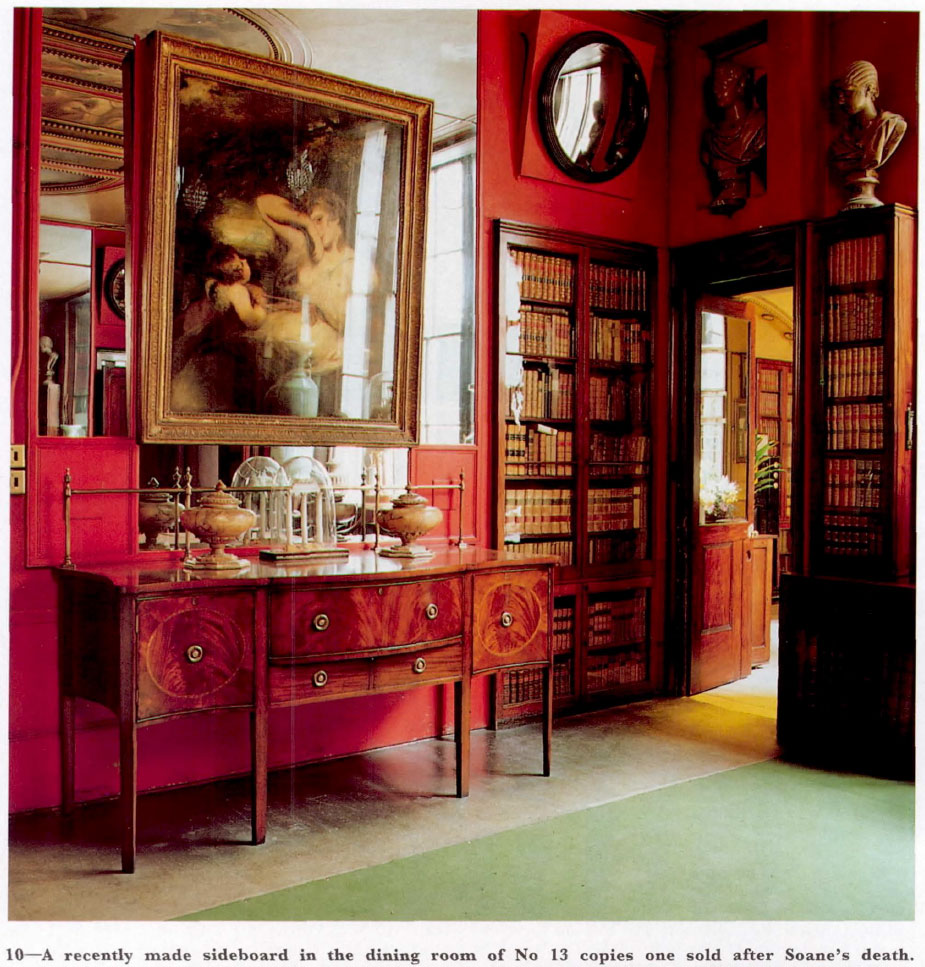

The restoration of John Soane's museum 'which raised the standards for the re-creation of a historic interior'

Sir John Soane despaired of his children to such an extent that he left his worldly goods to the nation,

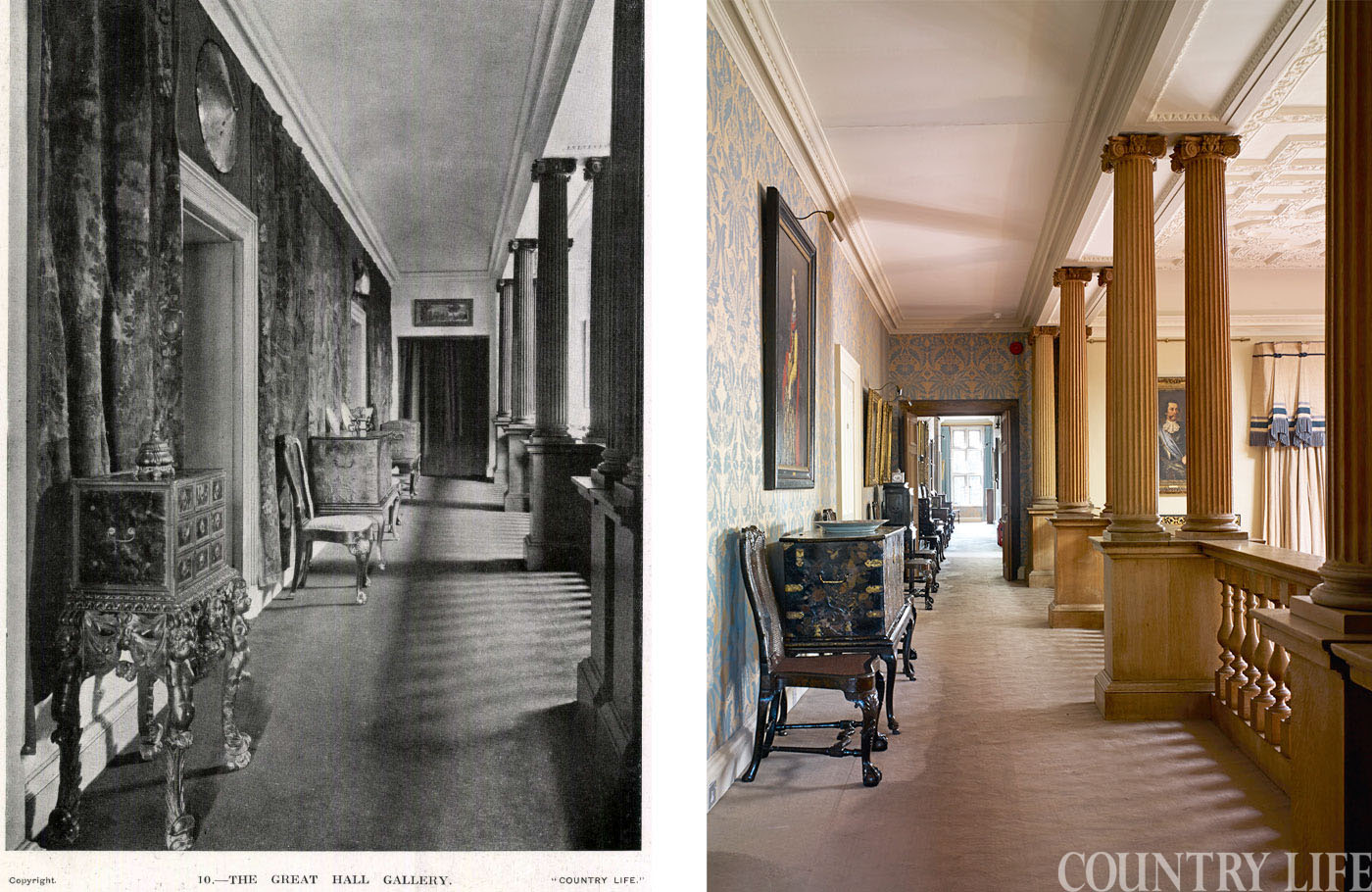

The stunning salvation of Castle Howard, one of the greatest houses in Yorkshire — and, for that matter, the world

The Herculean efforts which saved Castle Howard's architecture and collections after a devastating fire in 1940 have lasted for decades;

How Chequers has changed — and stayed the same — in a century, as pictured in Country Life

We take a look at Chequers is now, and as it was 103 years ago, when Country Life visited following

The oldest house in Britain — and how we were able to tell it apart from the other contenders

There are many nominations for the oldest home in Britain — in this piece from the Country Life archive, John Goodall

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.