Stansted Park, West Sussex: From royal favourite to stranger’s heir

John Goodall looks at the stages by which a medieval hunting lodge developed from the 17th century to become a great country house: Stansted Park, West Sussex, a property of the Stansted Park Foundation. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

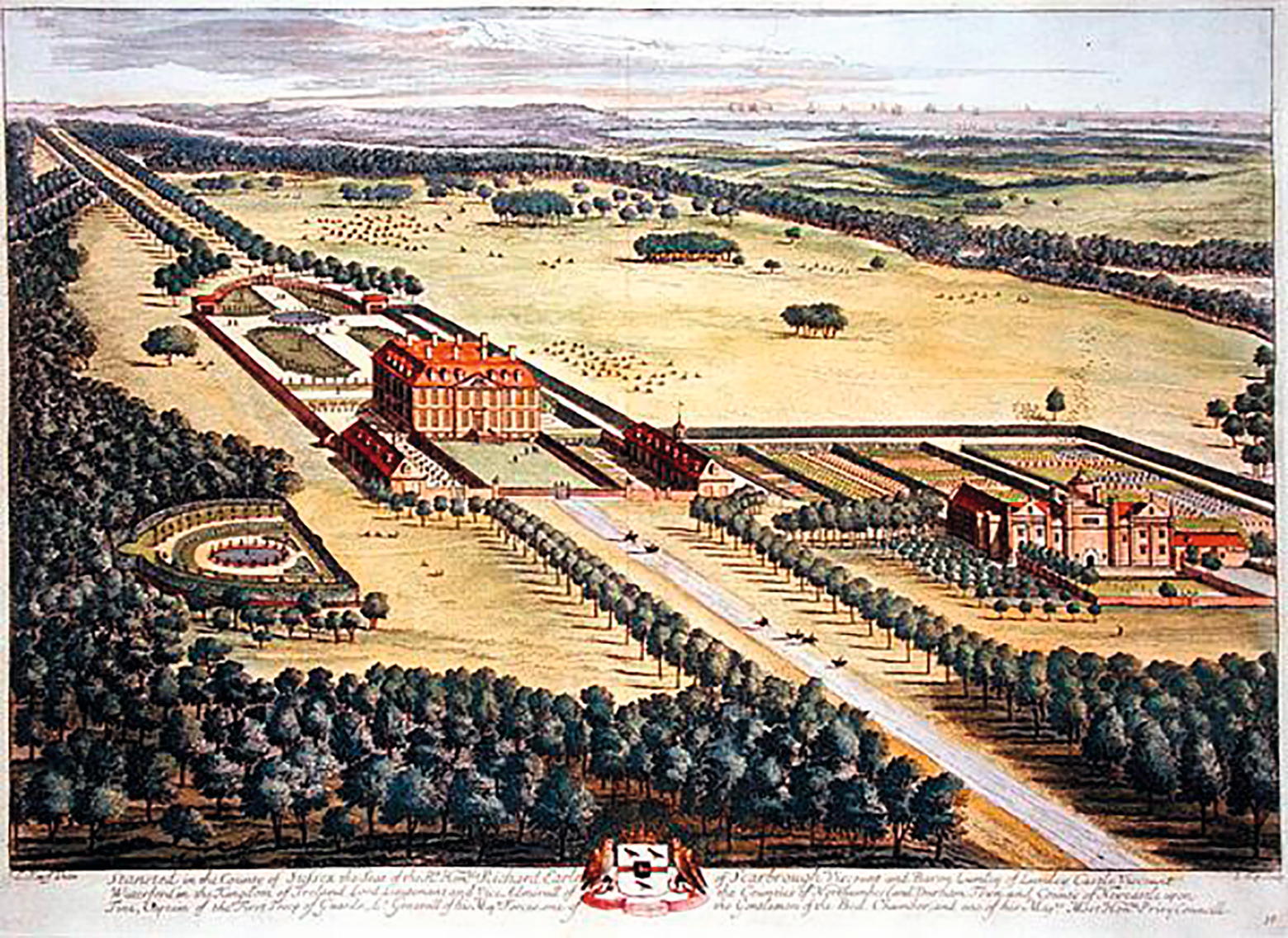

Chichester, the road, lying still west, passes in view of the Earl of Scarbrough’s fine seat at Stansted, a house, seeming to be a retreat, being surrounded with thick woods, thro’ which there are the most pleasant, agreeable, vistas cut, that are to be seen anywhere in England… [those that] sit in the dining room of the house… see the town and harbour of Portsmouth, the ships at Spithead, and also at Saint Helens; which, when the royal navy happens to be there, as often happen’d during the late war, is a most glorious sight.’ Much has changed to the setting of Stansted Park since Daniel Defoe visited in 1722, but the richly wooded landscape and spectacular views — which are central to the deep and fascinating history of the site — remain (Fig 1).

The story of the house can be traced back in the documentary record to the 12th century and the death of William d’Albini, Earl of Arundel, in 1176. In that year, the Earl’s landed possessessions, including Stansted, came into the hands of Henry II. There is no previous reference to a residence, but one must have existed because, in 1177, the King spent a week here. He also evidently enjoyed the hunting because, in 1178–81, the Pipe Rolls record the expenses of his falconers at Stansted and, then, between 1181 and 1184, the very substantial expenditure of more than £125 on the King’s ‘new chamber’, kitchen and ‘house’. His sons, Richard I and John, likewise made recorded visits, but, in the 13th century, Stansted reverted to the possession of the Fitzalan Earls of Arundel.

It was as a property of the Earls in 1327 that the first survey of ‘Stanstede’ was drawn up. It noted ‘a hall, two chambers with a chapel, a kitchen and a chamber over the gate, a stable and cowshed’. There were besides 60 acres of surrounding arable, nine acres of meadow and a fenced park, its grazing reserved for game. This modest property with its deer park attached probably continued in use as a hunting lodge until the late 15th century, when antiquarian sources assert — without obvious authority — that the Earl of Arundel bestowed it on his eldest son, Thomas Fitzalan. Thomas was married at the age of 14 to the Queen’s sister, Margaret Woodville, in 1464; created a Knight of the Garter in 1474; and summoned to Parliament as Lord Mautravers in 1482 (although, confusingly, he attended by the same title in 1471). All these events might reasonably have demanded the establishment of an independent household and seat.

No less mysterious than the timing of the gift is the question of what Fitzalan did with Stansted. The tradition is that he transformed it into a grand residence of brick, presumably before his inheritance of the Earldom in 1487. Some fragments of a brick building dating to the decades around 1500 are now incorporated into an early-19th-century chapel close to the house (Fig 2). These, in turn, seem to be the cannibalised remains of a courtyard with a low gatehouse that was depicted by Hieronymus Grimm in a watercolour of 1782. Whether this courtyard was merely an addition to the existing buildings on the site, however, or the surviving fragment of a grand new residence is not now clear. The former is most likely. That Fitzalan did undertake some work to the property is suggested by the appearance of his coat of arms in the neighbouring church of Westbourne.

In 1579, Stansted passed by marriage into the possession of the Catholic John, Lord Lumley, a celebrated collector, bibliophile and genealogist. He entertained Elizabeth I at the house in 1591 and possibly also Henry, Prince of Wales in 1603, but it was never a property to rival either his family seat at Lumley Castle, Co Durham, or the former palace of Henry VIII that he also enjoyed at Nonsuch, Surrey. Lord Lumley’s heir in 1609 was a cousin, Richard Lumley, who was created Viscount Lumley of Waterford in 1628. Unhappily married to the redoutable Elizabeth, née Cornwallis, he seems to have spent much of his time in Stansted. In 1638, as Civil War loomed, he was ordered to return to Lumley Castle, which he later garrisoned for the King. Stansted was the scene of at least two minor skirmishes during the fighting and, when Viscount Lumley eventually compounded with Parliament, he complained of the illegal felling of timber in the park.

In 1661, soon after the Restoration, the Viscount was succeeded by his grandson, another Richard Lumley. A favourite of Charles II, Richard accrued important Court appointments and was elevated to the peerage as Baron Lumley of Lumley Castle in 1681. Brought up as a Catholic, he went on to serve James II and raised a troop of cavalry during the Duke of Monmouth’s Rebellion in 1685. With its help, he subsequently captured both the Duke and his close ally, Lord Grey of Wark. Within a year, however, he fell out with the King and, in 1687, conformed to the Church of England. Thereafter, he became a leading figure in the planning of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 that installed William of Orange on the throne. His reward was ennoblement as Earl of Scarbrough in May 1689.

At some point in this sequence of events the Baron began work to a grand new house at Stansted. The date generally given is 1686 and derives from a much later antiquarian account published by James Dallaway in A History of the County of Sussex (1815). Dallaway goes on to attribute the design to the architect and collector William Talman and describes it as being erected on ‘new foundations’. He also compares the house with nearby Uppark, which was begun in about 1690 by Talman for Lumley’s former prisoner, Lord Grey (who was also rewarded for his support of the Protestant succession with elevation to the peerage as Earl of Tankerville in 1691). Dallaway’s dating and attribution have both been called into question, but they are perfectly plausible, even if we don’t know the source of his information.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The new house assumed the austere Classical form pioneered in England during the mid 17th century and adopted by architects such as Sir Roger Pratt: a brick box nine window bays wide and six deep. It comprised two main floors raised above a basement and was crowned by a hipped roof that was set with dormers and two serried ranks of chimneys. There were newly fashionable sash windows throughout, which allowed those inside to enjoy the extensive views, and the only external enrichment was a central pediment to the west. The main entrance to the house was enclosed within a walled forecourt and two long, low ranges, one of which was probably an orangery. A short distance away, to the south-west, the remains of the earlier house — Lord Mautraver’s gatehouse courtyard — were converted into stables.

An aerial view of the property (Fig 4), with its formal gardens and avenues, appeared in the compilation of engravings showing the principal houses of the kingdom entitled Britannia Illustrata (1714).

As for his neighbour Lord Grey — with his family seat at Chillingham Castle, Northumberland (COUNTRY LIFE, February 7), and his new house at Uppark — Stansted constituted a modern seat for the Earl of Scarbrough within striking distance of the Court and London. Its austere Classicism breathed the confident spirit of the Protestant order that supported William III’s accession and aped his Dutch tastes. Theirs was an imperial Britain, locked in European conflict for global ascendancy and aspiring to the status of a second Rome. The point was underlined internally by a series of Brussels tapestries depicting The Arts of War, commissioned either by the Earl or his son, possibly at the behest of the Duke of Marlborough, with whom they both served.

The Earl of Scarbrough died in 1721 and his estate and title were inherited by his eldest surviving son, another Richard, a soldier. His architectural interests were focused on Lumley Castle, which he commissioned Sir John Vanbrugh to improve in the 1720s. Richard committed suicide unmarried in 1740 and Stansted passed — independent of the Earldom — to a younger, spendthrift brother, James or Jemmy. He died in 1766 deeply in debt and left the property to a nephew, the courtier and politician George Montague-Dunk, Earl of Halifax. His ownership of Stansted lasted only five years, during which he made improvements to the park, including the construction of a domed temple and a Gothic folly, Racton Tower, attributed to Theodosius Keene (but perhaps by his father, Henry, given that he was a teenager at the time). He also paid for a spire on the neighbouring parish church of Westbourne.

A decade after Lord Halifax’s death in 1771, Stansted was offered for sale and snapped up by the Calcutta-born ‘nabob’ Richard Barwell, an East India Company council member who had just returned to Britain. His fortune, much of it doubtfully acquired, allowed him to purchase the estate outright for £102,000 and, with the help of the architects Joseph Bonomi and James Wyatt, he set about improving it. According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, he worked ‘in a style of expense which contributed to exhaust the oriental treasures by which it was supplied’. The main block was heightened, encased with whitened brick (to resemble stucco) and augmented with two-storey porticos to the east and west (similar in form to that created by Wyatt at neighbouring Goodwood). At the same time, new wings were connected to the main block by sweeping colonnades. Capability Brown was also employed to improve the landscape.

Barwell died at Stansted House on September 2, 1804, and was buried in Westbourne, where his monument by Nollekens remains. His gambling, political ambitions and many extravagances exhausted his fortune and the house was once again sold, this time to a man of totally different stamp. Lewis Way was born into modest prosperity and diverted from his desire to become a clergyman by his father, a Buckinghamshire squire. He unexpectedly came into a vast fortune, however, when a complete stranger who shared his surname made him his heir. He purchased Stansted and then set out to turn his wealth to account. Improbably, a story regaled to him about a stand of oak trees he happened to ride past in Devon converted him to the evangelical cause of the conversion of the Jews to Christianity and their return to Palestine.

Way pursued these aims with a curious combination of energy, ambition and amateurism. He travelled to Russia to meet the Czar and attended the conference of European sovereigns at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818 to plead his case. In the meantime, he also planned to establish a college at Stansted. To this end, he created an extraordinary chapel in the remains of Lord Mautraver’s buildings. The magnificent interior comprises a stark nave (Fig 5) and opulent chancel (Fig 7), the latter combining Jewish iconography in the glass, by Joseph Backler, with rich Gothic detailing. There is a large font for adult baptisms (Fig 6). No record of the architect is known. The anticlerical poet John Keats attended the consecration of the chapel — of which he deeply disapproved — in 1819 and the experience seems to have inspired some stanzas in The Eve of St Agnes.

Even by the time of the consecration, Way’s fortune was beginning to dissipate. Unable to bring his college to fruition, he first leased, then sold Stansted in 1826 to Charles Dixon, a wealthy wine merchant. Dixon employed the architect Thomas Hopper to reconfigure the house, demolishing the Regency wings and creating a new stable wing (Fig 3) to the north of the main block.

After his death in 1855, his widow lived in the house until 1871 and then bestowed it on her grandson, George Wilder. An enthusiastic traveller and amateur sportsman, under his ownership the house enjoyed a golden late-Victorian era. This was brought to a dramatic close by a catastrophic fire in 1900. This introduces the modern story of the house, which we will explore next week.

Visit www.stanstedpark.co.uk to find out more

My five favourite castles, by Country Life's Architectural Editor John Goodall

Listen to Dr John Goodall on the Country Life podcast as he names his five favourite castles in Britain — and

'One of the great landmarks of the Sussex coast', finally finished some 156 years after work was started

John Goodall looks at the recent completion of the chapel of Lancing College, one of the great landmarks of the

Chillingham Castle: 'Curiosity and beauty' at a spectacular castle that survived ruin by the skin of its teeth

Chillingham Castle, Northumberland — the home of Sir Humphry Wakefield Bt and the Hon Lady Wakefield — is a castle saved from

World exclusive: Inside Windsor Castle, by kind permission of the Sovereign

As the new reign begins, John Martin Robinson takes an exclusive look at Windsor Castle, Berkshire — an official residence of

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.