St Paul's Cathedral: Part church, part street spectacle, all masterpiece

St Paul's may not have the London skyline to itself as it once did, yet Sir Christopher Wren's masterpiece still holds its own in a century full of glass and steel. Jack Watkins takes a look at this extraordinary building and its chief creator.

An inscription, Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice (“Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you”), in the crypt serves as a memorial to Sir Christopher Wren, who is buried there. It’s a modest epitaph in an immodest building. Not everyone is infatuated with the pomp and grandeur of London’s largest cathedral, but it works as a street spectacle.

The most exciting approach is from the end of Fleet Street as it dips into the valley of the now subterranean River Fleet, affording a suspenseful preview of one of Wren’s Baroque towers, the giant dome looming beyond.

The gradient rises again up Ludgate Hill and you get a glimpse of another of the towers around a curve in the road, before the entire monumental edifice rolls into view.

Yet there are other viewing points: the angle from the south-east, favoured by photographers, offers a fine prospect of the great dome and lantern, the clouds circling above. Pleasing, too, is the walk through the north churchyard (currently partly closed for construction work), taking in the beautiful stone carvings, by Grinling Gibbons and other masons, around the windows.

St Paul’s Cathedral may be high and mighty (510ft long, 479ft wide at the transepts and rising to 365ft at its lantern top), but its predecessor was even bigger (585ft long, with a 498ft spire). Had it stood, we might have been marvelling at that wonder of Western Christendom, but when the Great Fire of 1666 reduced Old St Paul’s to a pitiful ruin, Wren was handed the chance to build the only one of Britain’s large cathedrals to be in the Classical style.

St Paul’s Cathedral in words

“One half of St Paul’s was built to hide the other half” A.W. N. Pugin

“No wonder that Cockneys love it, and see it as a badge as well as a symbol”Ian Nairn

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

“The dome of St Paul’s, one of the most perfect in the world”Nikolaus Pevsner

“Even in this modern age of advanced techniques, [it] remains breathtaking in its serene solidity, however often it is seen”Eric de Maré

Although hailed a masterpiece when the wraps finally came off in 1711, it had undergone much revision, thanks to heavy-handed interference from, in Wren’s words, ‘incompetent judges’. St Paul’s is a compromise, mixing elements of Gothic, Classical and Baroque. Inspirations include the Banqueting House in Whitehall, the Val-de-Grace and the Louvre in Paris and the Pantheon, St Peter’s and Santa Maria della Pace in Rome.

The long, high nave and choir is a medieval Gothic throwback, but at least, albeit via sleight of hand, Wren got his Italian dome, as wide as the nave and aisles put together. A dome on that scale, sitting on a high drum with an elegant colonnade, could make the building beneath look small and inadequate, so he created the appearance of a two-storey structure by adding a second level of walling above the aisle walls, although behind it lay only open space. This sham did, however, serve to conceal the anachronism (in Classical terms) of the flying buttresses required to support the vault and counter outward thrusts created by the weight of the dome.

The dome, too, is not quite as it seems. There are actually two, an inner one for internal effect, and a larger outer one to satisfy the landscape aesthetic, made only of lead-covered timber. The lantern tower and cross that seem to rest upon it are, in reality, supported by a huge brick cone that sits between the two domes.

Inside, the grandest section is beneath the dome, where Wren, in old age, had a special chair on which to sit and ponder. The choir stalls were by Gibbons, who took inspiration for his cherub head carvings from faces he saw in the street. The iron gates are the work of Jean Tijou. They remind us that within Wren’s masterplan were many other contributors.

The Whispering Gallery is only for those with a head for heights. Victorian guidebooks used to say the only thing worth seeing here were the monuments and memorials. We see it differently now, even if, in the age of glass cages, St Paul’s no longer dominates the Thames skyline in the way it once did.

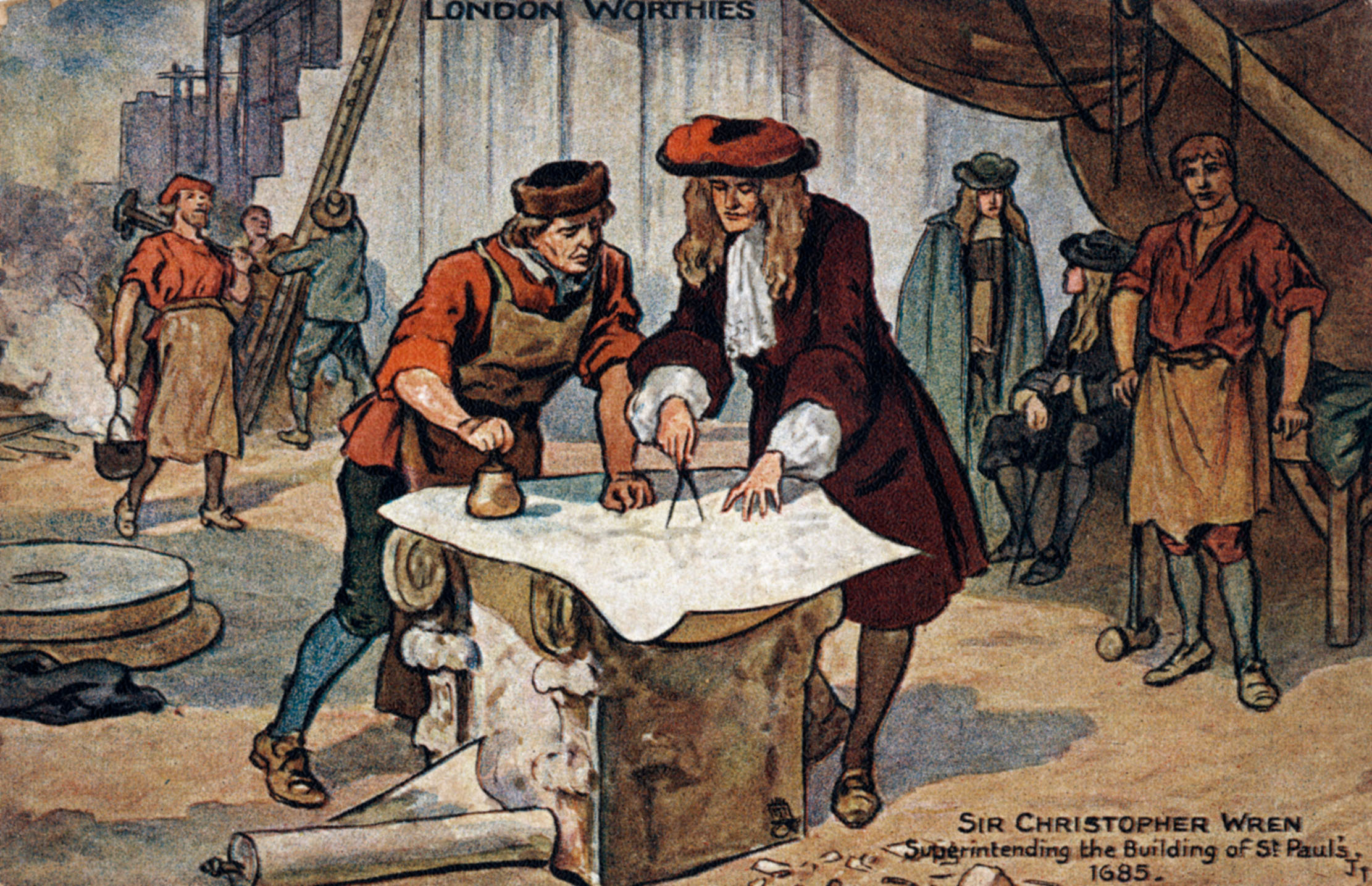

The Genius of Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723), the great allrounder, was a scientist before he turned architect. An original member of the Royal Society and a professor of astronomy who created models of the solar system and the moon, he was described by Sir Isaac Newton as one of the three greatest geometers of the age. His skills in drawing led to an interest in building design; among his earliest commissions was the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford (1663).

Even before the Great Fire, Wren had produced a plan for the rebuilding of Old St Paul’s and, after it, launched a radical new scheme to rebuild the City on the more spacious, formally planned lines of Paris. Although the level of compulsory purchases required to bring this about proved unacceptable, it earned him the post of Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, a position he held until he was 86.

Wren oversaw the reconstruction of 51 new City Churches, many of which survive today, adding immensely to London’s character. Among his outstanding secular buildings are the Fountain Court at Hampton Court Palace, Greenwich Hospital and Trinity College Library, Cambridge.

London has never been this quiet in 2,000 years — here's what it looks like, and what we can learn

In all of its 2,000-year history, it seems unlikely that the City of London has ever stood so silent as

Somerset born, Sussex raised, with a view of the South Downs from his bedroom window, Jack's first freelance article was on the ailing West Pier for The Telegraph. It's been downhill ever since. Never seen without the Racing Post (print version, thank you), he's written for The Independent and The Guardian, as well as for the farming press. He's also your man if you need a line on Bill Haley, vintage rock and soul, ghosts or Lost London.

-

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanship

London Craft Week: Rolls-Royce demonstrates the true beauty of real artisanshipA triptych of British nature scenes show that the difference between manufacturing and art is not as wide as we might think.

-

Name that dog: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 13, 2025

Name that dog: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 13, 2025One of Britain's most picturesque streets and Tom Brown's school find their way in to Tuesday's quiz.