St James's Palace: An exclusive look inside the British monarchy's oldest, quirkiest and most mysterious palace

Created as a secure residence for Henry VIII’s heir, St James’s Palace has become the modern home of the Court. Simon Thurley, editor of a new history of the palace, explains the remarkable history of this little-known building. Photographs by Will Pryce.

For most people, St James’s Palace is rather mysterious. Unlike its grand near neighbour Buckingham Palace at the head of the Mall, with its obvious role and famous appearance, St James’s is an odd, messy-looking building (Fig 13), the purpose of which is not well understood. Until Queen Victoria moved into Buckingham Palace in 1837, however, St James’s had been the principal seat of the British monarchy for more than a century and, before one-third of it burnt down in 1809, it was much more architecturally impressive.

The history of St James’s Palace properly begins in the reign of Henry VIII. The King, deeply in love with Anne Boleyn and filled with enthusiasm for a new start, commissioned Whitehall Palace, the largest building project of his reign. In 1532, to the rear of this riverside residence, he purchased land for a hunting park, which would be enclosed by a 12ft-high wall. The bounds of this were almost exactly coterminous with St James’s Park today and, in its north-west corner, there stood an almshouse in the possession of Eton College, the Hospital of St James.

The site of the hospital — in its secure parkland close to Whitehall — was ideal for the son and heir that Henry VIII was convinced Anne would bear him. He therefore cleared the existing buildings and commissioned an entirely new residence of red brick with stone dressings, the fashionable materials of the time. It comprised four courtyards: an entrance court approached by a gatehouse, which still stands at the bottom of St James’s Street (Figs 1 and 4); an inner courtyard containing matching sets of lodgings for the intended Prince and Princess of Wales, an inner privy court for private lodgings and a courtyard of kitchens. Very unusually, there was no great hall, perhaps part of the policy to restrict access to the royal children. There was, however, a large chapel.

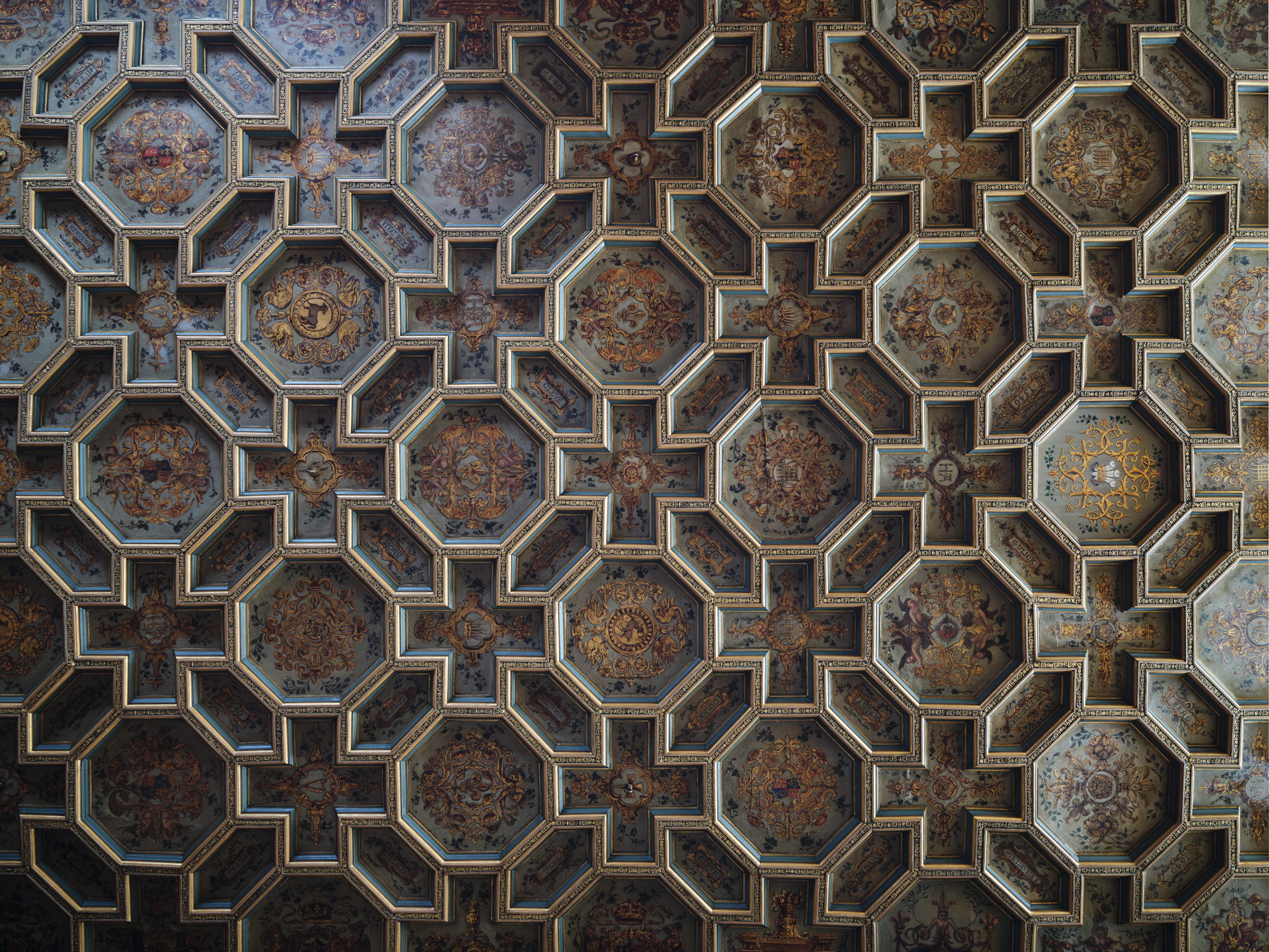

The Tudor chapel at St James survives, although much molested in later times (Fig 10). It is far less architecturally assertive than its 1530s counterpart at Hampton Court, but likewise incorporates an elevated royal pew (Fig 9). Work to it began in 1531–32 and the interior was probably covered by the present ceiling, painted with the initials H & A for Henry and Anne Boleyn (not Anne of Cleves, as some authorities have suggested), by 1533–34. It thus pre-dates the publication of the architectural treatise by Sebastiano Serlio in 1537 that popularised the cross-pattern of the ceiling (Fig 11).

The figure behind the many and complex land transactions that made the construction of Whitehall and St James possible was the King’s secretary, Thomas Cromwell. As chief minister, he was given licence to use the unfinished house at St James’s and it was when he was there that he gave orders for the royal painters to retro-fit the ceiling with new panels bearing Anne of Cleves arms. Luckily, she had the same initial as her predecessor, saving the painters time, but this explains the confusion over their identification.

St James’s was not finished in time for occupation by Edward VI, but the palace did become home to the children of the Stuart kings. The principal alteration made to the Tudor buildings in this period was the addition of a Roman Catholic Chapel (Fig 14). This was conceived as part of the negotiations for a marriage between Charles, Prince of Wales (the future Charles I) and the Spanish Infanta in 1623 and completed as part of the marriage treaty between Charles and Henrietta Maria. Designed by Inigo Jones, it came to play an important part in the decisive constitutional events of the 17th century.

The Protestant Stuarts faced a dynastic conundrum. Most European royal brides were Roman Catholic, but, to enjoy the diplomatic, economic and dynastic advantages they brought, it was necessary to weather fierce anti-Catholic sentiment at home. Charles I, Charles II and James II all married Roman Catholic princesses, each of whom required religious and architectural dispensations to worship in England.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1623, Jones was ordered to prepare designs for a chapel for St James’s ‘with great state and costliness’ and the project proceeded with remarkable speed. After only 11 days, designs were sent to Spain for approval and, without waiting for a reply, Jones submitted a construction estimate the day after. One day later, the Spanish Ambassador laid the foundation stone marking it with a cross.

The new chapel stood to the east side of the palace and was connected to the princess’s rooms by a gallery. The design had to adhere to the (lost) specification from the Spanish royal household, but, more significantly, drew on the most up-to-date ecclesiastical architecture Jones had seen in his two trips to Italy. Of these, perhaps, the most important was the small church of Santa Maria Nova attached to the Augustinian convent in Borgo Porta Nuova in Vicenza, which was completed in 1590 and was almost certainly designed by Andrea Palladio.

Like the Tudor chapel, Jones’s Chapel at St James’s has been much altered, but intelligent restorations in the 1930s and 1950s have reclaimed much of his original intention. Internally, it was a double cube. The west end contained the royal closet, elevated and separated from the body of the chapel by a screen with Corinthian pilasters and festoons. The ceiling is barrel vaulted, with square coffers based on Palladio’s reconstruction of the Roman Temple of the Sun and the Moon in Rome and the east window is the first use in England of what became known as a Serlian or Venetian window (Fig 12).

When Henrietta Maria arrived on English shores in 1625, she was accompanied by 12 Oratorian priests, who established themselves at St James’s, publicly celebrating Mass for the first time in England since the reign of Mary I. This was a public chapel open, by the terms of the Queen’s marriage treaty, to all English Catholics. As this inflamed zealous Londoners, tensions increased at Court. When the King and Queen dined together in public, their Catholic and Anglican chaplains vied to have their own Grace heard loudest. As it became a shouting match, the King grabbed the Queen and left the table in a fury.

At the end of July 1626, the Oratorians and the majority of the Queen’s French household were expelled. Nevertheless, the Catholic chapel remained a focus of both Catholic worship and opposition to a French Queen who was thought to bring ‘the Pope and the Devil’ into the English Court.

Between 1630 and 1637, Henrietta Maria gave birth to five children at St James’s Palace, ending up believing that it was her lucky place for childbirth. All her children were baptised Anglicans; Prince Charles — the future Charles II — was the first in 1630, being christened by the richly coped bishop of London in the Tudor chapel. As he was lifted high above the font, trumpets and drums were the signal to hoist a flag on the gatehouse of St James’s, this being spied by a lookout on the Whitehall Banqueting House, whereupon a rooftop brazier was lit. Once that signal was spotted from the top of the White Tower at the Tower of London, the order was given to fire the castle’s cannons and to let off ordinance from the naval vessels in the Pool of London.

Charles I and Henrietta Maria were devoted parents and spent much time at St James’s with their large family (Fig 2). Steps were removed from doorways to prevent the toddlers from tripping up and a swing was hung in the long gallery. There was a schoolroom and a library and Charles I began to amass some of his art collection here. When the Civil War interrupted the long Stuart peace, however, the Roman Catholic chapel became a target. It was despoiled and there were calls for its demolition, but Parliament decreed that it be converted into a public library.

In 1698, a ferocious fire ripped through Whitehall Palace, which had been the centre of English government for more than 150 years. William III swore to rebuild, but despite some ambitious plans drawn by Sir Christopher Wren, he had neither inclination, time nor money to push such a project forward. He also knew that, widowed and childless, the throne would pass to his sister-in-law, Princess Anne. In preparation for her accession, William had already handed over St James’s Palace to her and she had commissioned a large new ballroom on the north side in the former kitchen court. It was the first purpose-built ballroom in any English royal residence and, despite Anne’s reputation for being joyless and dull, it was heavily used during her annual cycle of Court balls.

When William III died in 1702, St James’s became Queen Anne’s principal residence of state. Wren was commissioned to build a vast new council chamber 48ft long, signalling the importance of this body to her rule. It contained a council table covered in a carpet with 30 chairs and, at its head, a chair of state under a canopy for the Queen. The walls were draped in tapestry on which hung silver sconces; over the doors to the waiting room and stairs were portraits of doges of Venice.

Next to the council chamber was an audience room, a new name for this important interior. Here, when her health allowed it, Anne held her thrice-weekly Drawing Rooms, sitting on a chair of state beneath a canopy surrounded by her ladies in waiting. Jonathan Swift claimed, in 1711, that he generally knew between 30 and 50 people at the Queen’s Drawing Room; the gathering he said ‘serves me as a coffee-house, once a week I meet acquaintance that I should not otherwise see in a quarter’ there could be found ‘all her Ministers, Foreigners and Persons of Quality’.

George I made few changes to St James’s, but his son, George II, added a fine new kitchen and stable range. His Queen, Caroline of Ansbach, also commissioned William Kent to build her a new library in 1736 (COUNTRY LIFE, January 12, 2022). But for her death in 1737, it would have been one of the finest rooms in London, a freestanding structure housing some 3,000 volumes, mostly French works, in 21 bookcases surmounted by Rysbrack terracotta busts. The building was demolished for the construction of what is now Lancaster House.

In 1762, George III purchased nearby Buckingham House for the Queen and they liked it so much that it became their London home, setting aside St James’s for official and ceremonial functions. It was here that George III received John Adams, the first Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States of America. Adams recalled the general embarrassment as he waited. When he went ‘through the Levee Room into the King’s Closet, the Door was Shut, and I was left with his Majesty and the Secretary of State alone. I made the three Reverences, one at the Door, another about half way and the third before the Presence’. The King then observed: ‘I was the last to consent to the Separation: but the Separation having been made, and having become inevitable, I have always said as I say now, that I would be the first to meet the Friendship of the United States as an independent Power.’

By 1800, the palace was full to bursting with not only ministers and courtiers, but with the apartments of the many children and relatives of George III and Queen Charlotte. George, Prince of Wales, had been lodged at Carlton House on Pall Mall since 1783, but William, Duke of Clarence, was given rooms at St James’s, which, in the 1820s, became a large and comfortable mansion known as Clarence House. Edward, Duke of Kent, also had apartments at the Palace, although he rarely used them. The youngest son, Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, was allocated apartments at the south-eastern corner of the Palace, overlooking St James’s Park.

It was in the Duke of Cambridge’s apartment that, at 2am on January 21, 1809, a huge fire broke out. In its aftermath, a quarter of the palace was left in ruins and, despite the continued use of the state rooms by George III, the eastern court was still a pile of rubble a decade later. This was the lowest point in the architectural history of the monarchy. As Britain emerged as the leading world power, the official residence of its sovereign was in a chaotic, half-burnt 250-year-old palace without prestige, presence or grandeur. The problem was that St James’s was never designed to be an impressive architectural symbol.

There was widespread consciousness of the problem. In 1823, for example, the Morning Post stated bluntly that: ‘The outside will never look like a royal palace until the brick walls shall have been covered with a stone facing ornamented with pillars and porticoes.’ The following year, an MP said in the House that: ‘St James’s Palace looked more like an almshouse than a kingly residence, and was a disgrace to the country.’

It was George IV who rescued both St James’s and the architectural reputation of the monarchy. On coming to the throne, he announced that he would move into St James’s until Buckingham House was fitted up as his permanent residence. The temporary fitting of St James’s, as was usual with the King, turned into an extravagant rebuilding of the state and private apartments. It has recently been discovered by Michael Turner that George IV’s works to St James’s were not designed by John Nash, who was completely absorbed by the Buckingham House project, but by Thomas Frederick Hunt, a pupil of Sir John Soane. Hunt was a capable designer, but a spendthrift who went bankrupt and had to hide from his creditors in rooms at the top of the palace gatehouse.

The work cost the vast sum of £40,000, plus another £20,000 for Clarence House (COUNTRY LIFE, November 14, 2018). Hunt set out to make a new entrance to the palace opposite the Queen’s Chapel in what is now Friary Court. He was an expert in Tudor styles and his entrance colonnade is an early and successful essay in the Tudor revival. In the surviving Tudor state rooms, after discovering an original Tudor fireplace, a pair to it was made in the adjoining room, where a new ‘Tudor’ bay window was also added.

These Tudoresque rooms, now called the Armoury (Fig 5) and the Tapestry Room (Fig 6), were reached by Hunt’s masterpiece, the Grand Staircase (Fig 3). This scissor stair, embellished in the French taste in 1904, takes visitors to the principal floor. Beyond the Armoury and Tapestry Room, Hunt added a third great room to Queen Anne’s state rooms on the south front in the style of Wren. Externally, the junction is almost invisible, but internally the three rooms of the new State Apartment — a grand enfilade focused on the royal throne (Fig 8) — were decorated in the King’s taste for late-18th-century France and hung with vast canvases celebrating English naval and military victories (Fig 7).

St James’s remained the official place for state functions until 1837, when the young Queen Victoria moved to Buckingham Palace, and continued to host levees until 1939. It still remains, however, the senior palace in the realm. Ambassadors are accredited to the Court of St James and it is at St James’s where a new sovereign is proclaimed. As Prince of Wales, The King lived in Clarence House, an integral part of the palace, and his offices, with those of his charities, are accommodated nearby. Meanwhile, the St James’s state apartments play host to events in support of organisations patronised by members of the Royal Family. For the first time this autumn, there have been public tours of the interior and the hope is that this mysterious palace will gradually become more familiar.

A new history ‘St James’s Palace: From leper hospital to royal court’ (2022), edited by Simon Thurley, is published by Yale University Press in association with the Royal Collection Trust (£60). For information about future tours, visit www.rct.uk

13 beautiful palaces where guests are welcome, in Britain and beyond

Hazel Plush takes a look at the magnificent palaces where guests are welcome.

Blenheim Palace: The tale of the only country house to be granted the title 'palace'

With its 856ft-long, exuberant frontage, Blenheim Palace is the crowning glory of Vanbrugh's work. Jack Watkins takes a look at

-

‘Reactions to the French in the 1870s varied from outrage to curious interest’: Impressionism's painstaking ten year journey to be taken seriously by the Brits

‘Reactions to the French in the 1870s varied from outrage to curious interest’: Impressionism's painstaking ten year journey to be taken seriously by the BritsClaude Monet and Camille Pissarro spent time in London, but it took James McNeill Whistler to act as artistic bridge with Britain and the ‘sweetened’ Impressionism of Jules Bastien-Lepage to inspire most homegrown painters.

-

Rogue sellers and puppy farmers are exploiting Government licensing loopholes at the expense of responsible dog breeders, says The Kennel Club

Rogue sellers and puppy farmers are exploiting Government licensing loopholes at the expense of responsible dog breeders, says The Kennel ClubThe Kennel Club launched a report in the House of Commons last week calling for an urgent review of current licensing regulations.