St George's Hall: Why the world’s greatest neo-Classical building isn’t in London, Paris or Rome — it’s in Liverpool

The combined demand for a concert hall and a set of law courts in the burgeoning Atlantic port of Liverpool during the 1840s brought into being one of the greatest public buildings of the Victorian age.

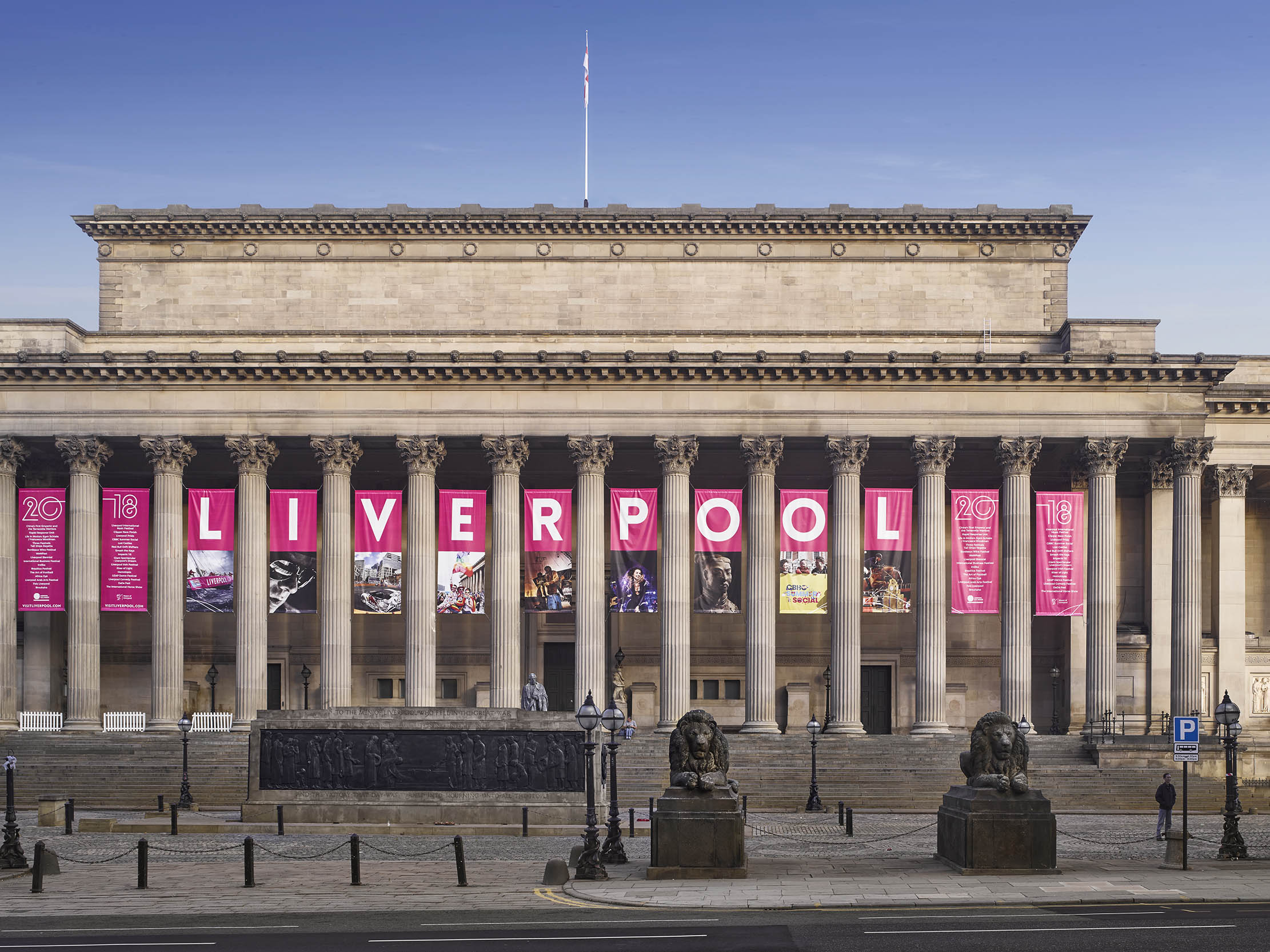

Emerging from the broad, light-filled Victorian shed of Lime Street Station, the modern rail traveller to Liverpool is confronted by a tremendous sight. Facing them across a broad square is an immense neo-Classical building of great and noble beauty, Roman in architecture and heroic in scale, superbly well made, its broad porticos of Corinthian columns expressing civic pride and exuding confidence. Its story is as unexpected as it is remarkable.

One feature of Liverpool’s cultural life in the early 19th century was triennial music festivals held in aid of local charities. These featured choral concerts, in particular performances of oratorios, but the town had no adequate venue for them. Therefore, in 1836, a group of cultured Liverpudlians got together and formed a company to promote the construction of a new concert hall, to be funded by the sale of £25 shares.

By January 1837, they had raised £25,000 and the town’s corporation made a site available. In a rush of enthusiasm, a foundation stone was laid, rather prematurely, on June 28, 1838, to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Coronation.

On March 5, 1839, the committee advertised a competition for a design for the new building, ‘the cost not to exceed £30,000’. Of the more than 80 entries, they chose one by a complete unknown: a 25-year-old London architect called Harvey Lonsdale Elmes.

Inevitably, there were complications. On one hand, the money for the concert hall was slow to come in. On the other, Liverpool had become an assize town in 1835, so needed new law courts. The corporation held a second competition for these, in 1840. Again, there were about 80 entrants. Elmes entered it and, extraordinarily, he won this time, too.

The young prodigy who had pulled off this double first had grown up in West Sussex; his father was an architect and writer, best-known for his biography of Sir Christopher Wren, and his uncle was a successful builder.

Elmes worked in his uncle’s office, then for the distinguished Bath architect Henry Goodridge, before studying at the Royal Academy Schools and helping his father with a couple of commissions. Nevertheless, when Elmes won in Liverpool, he had never actually designed and built a whole building.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Something similar was to happen in 1903, when Giles Gilbert Scott won the competition to build the city’s new Anglican Cathedral at the age of 22. On both occasions, Liverpool took a chance on youth and brilliance and was repaid with a masterpiece.

Elmes’s design for the Assize Courts was, however, criticised and the corporation’s surveyor, Joseph Franklin, was asked to make designs. Elmes protested and was given the chance to revise his proposal.

The old town centre, down by the Mersey, was cramped, so he suggested erecting the new buildings on the hillside behind, forming two sides of a square, with the neo-Classical façade of Lime Street Station, just completed in 1837, forming the third.

The funds for the concert hall were still not adequate and, in 1840, the corporation agreed to take over this project, too. Elmes proposed combining both functions, the concert hall and the courts, in a single huge building. The corporation accepted this idea and Elmes produced his definitive designs in 1840. Construction began the same year.

In 1840, architecture in Britain was at a turning point. Classical architecture, in its various strands and interpretations, had been the dominant mode for prestigious buildings for 180 years or so. However, by 1840, the tide was turning in favour of Gothic, notably in the competition for the new Palace of Westminster. Nevertheless, Liverpool stuck with Elmes and heroic Classicism.

Elmes maintained his office in London, but regularly made the seven-hour train journey to Liverpool, where he acquired several more jobs. Unfortunately, however, he had a weak constitution and, in 1847, contracted consumption. In September of that year, he departed for Jamaica to winter in a warm climate, but died two months after his arrival there, at the age of 33.

Characteristically, he had exerted himself before leaving England to leave the drawings for St George’s Hall in good order. The work was taken over by the project engineer, Robert Rawlinson, and Dr David Boswell Reid was engaged to design the vast building’s elaborate heating and ventilation systems.

Rawlinson was a brilliant structural designer, but much remained to be done to complete the design of the interior and, in 1848, the corporation engaged the celebrated Classical architect Charles Robert Cockerell to advise on the works. In 1851, he was officially appointed architect to the building. Much of the detailing of the interior is Cockerell’s and he supervised the project until its completion in 1854, at a total cost of more than £300,000.

The plan of the building is clear and logical. Its huge central section contains the main Concert Hall, which is flanked by long corridors to either side as circulation spaces. He arranged the courtrooms at either end of the hall: the Crown Court to the south and the Civil Court to the north. On the long west side of the building, a series of spacious rooms housed other court-related functions. To the north end, there is also an oval concert room for chamber-music performances.

However, this simple description doesn’t begin to convey the power of the composition that Elmes wrought. Few neo-Classical buildings in Britain come anywhere near the originality and visual drama of St George’s Hall, which is conceived with great creative power and freedom from strict precedent.

Elmes’s work has been compared to that of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, whose work he saw on a trip to Germany in 1842, when he had finalised his external design. The great building seems to shift and regroup as you walk around it, changing its character on each façade. The east front, towards the station, has a portico, 16 columns wide, corresponding to the main concert hall. The Corinthian order is continued to either side as pilasters, which turn into free-standing piers as they rise, a wonderful departure from historic precedent.

To the south is a great eight-column temple portico raised high on a podium, an effect reminiscent of Romantic reconstructions of the Forum in Rome. The west side is high and severe. At its north end, the building culminates in a semi-circular bow, like the stern of a great ship, which groups beautifully with the magnificent row of public buildings that march up William Brown Street, including the Museum, the Picton Reading Room, the Walker Art Gallery and the County Sessions House. In between is the Wellington Memorial column.

These buildings came later, taking their stylistic cue from St George’s Hall and, with it, form a magisterial grouping.

To the east, the hall looks over St George’s Plateau, Liverpool’s main public open space. Cockerell adorned it with four lions and cast-iron lamp standards with dolphin bases. The plateau has attracted major public memorials, including the city’s great Cenotaph, designed by L. B. Budden, one of the finest war memorials in the country.

On this side, the building was adorned with a series of Classical relief sculptures added to the façade in 1882–1901, by Thomas Stirling Lee, C. J. Allen and Conrad Dressler.

St George’s Hall has main entrances to the south, east and north, depending on the occasion. The south portico was originally used by people attending court and is now mostly used by wedding parties. People attending events in the Concert Room use the north entrance and that in the long east side leads directly into the Great Hall.

However, since the building’s recent refurbishment, the daily visitors have used the basement-level entrance below the south portico. Here, there is a shop and a cafe and the normal public tour begins with the prison cells, which occupy a small part of the immense vaulted basement, before heading for the grander spaces upstairs.

The rest of the basement was only ever used as part of the ventilation system, but the empty spaces are nonetheless high and dramatic, with Piranesian rows of brick arches receding into the distance.

The main entrance to the great Concert Hall is from the east. This vast and splendid room is 169ft long, 77ft wide, and 82ft to the crown of the great barrel vault. Elmes was inspired by a reconstruction drawing of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome and marshalled the great space in five bays, separated by huge polished columns of red granite.

The great vault was built using hollow-pot construction, designed by Rawlinson, to lessen its weight. Its rich plaster decoration, like much else, was added by Cockerell; other elements of his design that stand out are the fantastically rich gilded bronze doors, with the proud emblem ‘SQPL’, associating Liverpool with the ‘SPQR’ of Ancient Rome, and the amazing floor of Minton tiles. This is one of the greatest achievements of Victorian ceramic art, the design marshalled in a series of huge interlocking circles.

Around the sides of the room are marble figures of Liverpudlian and national worthies, including a rather startling representation of George Stephenson, engineer to the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, in Greek guise.

The huge organ, on a gallery at the north end of the room, was built by Henry Willis and completed in 1855; with 7,737 pipes, it was the largest in the country at the time. It blocks the view through to the Civil Court, which had formed an important element in Elmes’s vision. The equivalent view at the south end of the room, through to the Crown Court, remains.

As befits its senior role, the latter court is elevated above the level of the former. Both are lined with polished granite columns and retain all their original fittings.

To the north of the Civil Court, there is the spacious North Entrance Hall, a beautiful space, with steps rising between Doric columns and reproductions of parts of the Parthenon frieze. Further stairs rise to the Small Concert Room above.

It hardly seems possible that that any interior could follow that of the main hall, but this is surely one of the most beautiful concert halls in the world. Almost circular, measuring 77ft by 72ft, it is surrounded by a balcony supported by graceful caryatid figures.

The balcony above them has a cast-iron balustrade whose undulating shape gives a wonderful sense of animation to the room. Cockerell devised the strikingly rich plaster decoration, which culminates in the columned and mirrored backdrop to the stage. The room was inaugurated in 1856.

The 1980s were a grim time for St George’s Hall, as they were for Liverpool as a whole. The courts moved out in 1984 to new accommodation and, for a while, incredibly, this great building was closed and disused, a haunting symbol of the city’s troubles.

Structural repairs began in the 1990s, enabling the Concert Hall to be reopened for public use in 1992. A major refurbishment of the whole building was carried out by the architects Purcell Miller Tritton in 2000–07 at a cost of £23 million — it was reopened by The Prince of Wales on April 23, St George’s Day. Today, the building is in regular use for concerts, exhibitions, antiques fairs, markets and a host of other occasions, as well as weddings and corporate events.

The revival of St George’s Hall’s mirrors the wider revival of Merseyside in the 21st century. It has long been recognised as one of the greatest of all neo-Classical buildings: neither London nor Paris has anything to match it. The Liverpudlian architect and teacher Sir Charles Reilly called it ‘the best Greco-Roman building in Europe’, but one might just as well say in the world.

For more details, telephone 0151–233 3020 or visit www.stgeorgeshallliverpool.co.uk

Credit: Paul Highnam / Country Life Picture Library

The Cathedral of Christ, Liverpool: The fascinating story of Britain's largest cathedral

The architect who created the red telephone kiosk and the London power station today occupied by Tate Modern also designed

Gothic for the Steam Age: An illustrated biography of George Gilbert Scott by Gavin Stamp

John Goodall is impressed by this concise and beautifully illustrated account of Scott's achievements.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher