St Bartholomew’s Hospital: 900 years of service

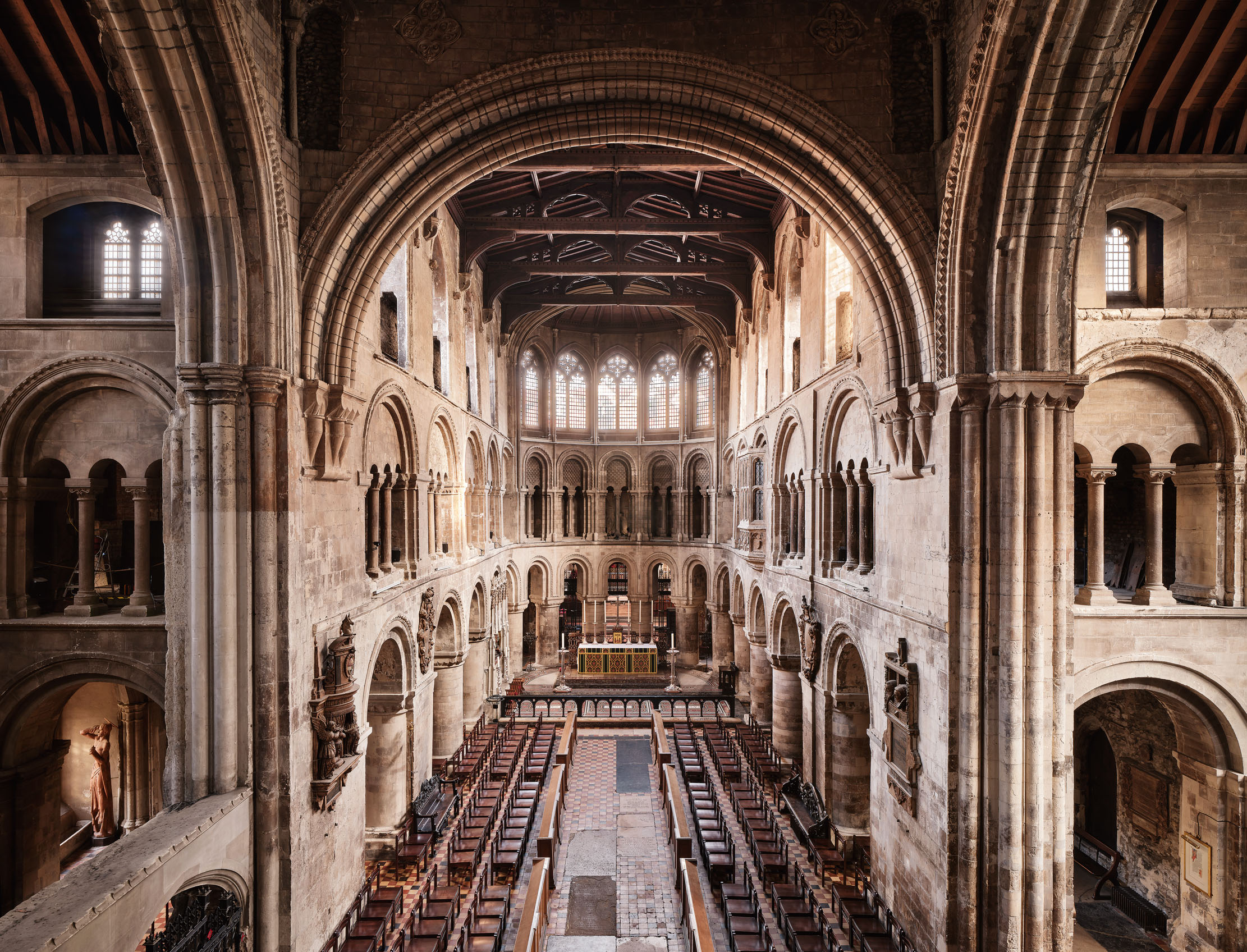

This year, two connected institutions in the heart of London — St Bartholomew’s Hospital and St Bartholomew’s Church — celebrate their 900th anniversary. In the second of two articles, John Goodall looks at their foundation story. Photographs by Will Pryce For Country Life.

St Bartholomew’s — or Barts, as it is familiarly known — celebrates its 900th anniversary as a living and working institution in 2023.

No other major hospital in Britain — or perhaps in Europe — can claim such extraordinrary longevity. Over that immense period, the hospital has changed beyond recognition in physical and institutional terms, but the site and the fabric of its buildings as they appear today embody an extraordinary story. They have touched the lives of untold numbers of Londoners at critical moments of need.

As we heard last week, the hospital shares its foundation anniversary with the neighbouring church of St Bartholomew-the-Great. The church was likewise begun in 1123 by one Rahere as the priory church of a community of Augustinian canons. Rahere governed both the priory and hospital, but, at his death, the institutions assumed a degree of independence without wholly breaking apart. The result was four centuries of episodic quarrelling over such privileges as the ringing of bells, rights of burial, the procedure of elections as ‘proctor’ or master of the hospital and the possession of votive images of St Bartholomew.

Frustratingly little is known about the early-12th-century hospital. The only documented building constructed for it in Rahere’s lifetime was a chapel, to which he gifted a relic of the Holy Cross. Its work was dependent financially on the priory and the generosity of Londoners. Indeed, the first hospital proctor, Alfhume, reputedly spent his time in markets begging for food that he could distribute to the poor. Only from 1175 did it begin to acquire property independent of the priory.

During the late 12th century, it’s clear from fragmentary evidence, the hospital community comprised a group of canons or priests and lay brothers, men acting under religious vows as servants. Women could likewise join the hospital community for life as sisters, again working as servants and occupying distinct lodgings with their own garden. The hospital by this date variously accommodated travellers and the sick. Ordinances issued in 1316 attempted to limit the community to seven brothers (including five priests) and three sisters. Notwithstanding this, six lay brethren witnessed a charter in 1330.

The walled precinct of the hospital, meanwhile, effectively developed as a London suburb. It was internally divided by two gated thoroughfares. The principal of these connected Smithfield Market to the north with a small postern in the City wall to the south. A second diverged from this route and meandered west to Aldersgate, one of the major northern gates of London. Rahere’s hospital chapel—now transmogrified into the parish church of St Bartholomew-the-Less—stood just inside the Smithfield gate. Immediately adjoining the chapel was the principal hospital cloister court with its infirmary. A second cloister stood at the intersection of the two thoroughfares a short distance away and overlooked a cemetery for burying the poor. This was not a regularly planned complex.

As the City grew, so did the precinct develop. In the 14th century, its perimeter began to be lined with rented tenements and, by the turn of the next century, hospital properties within the precinct itself were being rented out, some to powerful and wealthy individuals. This gentrification seems to have been actively encouraged, with careful improvements. In the 1430s, for example, the hospital—in concert with such neighbouring institutions as the Charterhouse and priory—improved the local water supply. It also rebuilt the main gate, with money bestowed by the will of the celebrated Richard Whittington.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Other bequests funded new chapels in the precinct and an extension of the hospital’s charitable activities in line with changing expectations and fashions. At least one school was established and there was an initiative to rescue infants from nearby Newgate jail.

In the mid 15th century, the hospital compiled a surviving summary of all its charters and property deeds, the St Bartholomew’s Cartulary. The principal figure involved, John Cok, offers us a brief autobiography. He was apprenticed to a goldsmith, attended the coronation of Henry V (in heavy rain) and became a servant of the Master before entering the community in 1420. His annotations and asides humanise this document. Cok latterly worked ‘with trembling hand’ and died in his late seventies, in about 1468.

In 1535, the annual revenue of the hospital was estimated at £371, making it one of the richest institutions of its kind in the kingdom (and the third richest hospital in London). The priory was dissolved in 1539, but, curiously, there is no document of surrender for the hospital. Its dwindling community seems to have limped along in increasingly straightened circumstances. The reason was probably brutally practical: the needs of London’s poor and sick had not gone away.

Religious foundations of one kind of another provided the framework of education and social care in early Tudor England. Through the institutions of the City, London responded to the Dissolution, petitioning for a whole raft of these institutions to be restored in a form that would be acceptable in the febrile, political and religious atmosphere of the moment. St Bartholomew’s Hospital was duly revived in 1544, but shorn of its endowment.

After two disastrous years, the City authorities tried again. The result was a royal charter dated December 27, 1547, constituting the ‘House of the Poor in West Smithfield of the Foundation of King Henry VIII’ (Fig 2). The name never caught on, but technically applied until Barts was absorbed into the NHS in 1948.

Jointly funded by the City and the King, the foundation of 1547 was established on a completely new institutional footing, under the direction of 12 civic governors. There was to be provision to lodge, clothe and feed 100 poor men and women, as well as a physician, doctor, matron and 12 women to attend them. Junior staff included a cook, butler and eight beadles, who were ‘to bring to the said late hospital… such poor, sick, aged, and impotent people as shall be found going abroad in the City of London and the suburbs’. Rahere’s chapel also became the parish church of St Bartholomew-the-Less, with one of the former brethren of the Augustinian hospital, Thomas Hycklyng, as its vicar.

The constitution of the new hospital continued to evolve in the face of London’s irresistible expansion over the next century. All that remained stubbornly unchanged was the chaotic organisation of the precinct, which remained in mixed and—from the mid 17th century—increasingly impoverished occupation. There were periodic improvements, such as the construction of the present Henry VIII Gatehouse (Fig 5), designed by the mason Edward Strong and begun immediately next to its medieval predecessor in 1702.

London, however, was by now emerging as an imperial capital and its public institutions were assuming much more ambitious forms. Since the Great Fire in 1666, the royal hospitals at Chelsea and Greenwich had established a new architectural standard for such buildings. Bethlem (Bedlam) Hospital was likewise rebuilt, Guy’s founded and even the notorious Bridewell was improved before the Governors of Barts finally determined to rebuild their institution.

The crucial figure in the project, who became a trustee in 1723, was the architect James Gibbs. Trained in Rome, he built his career in London on the back of his splendid new church St Mary-le-Strand, erected in 1714–17. He presented plans for the new hospital in July 1729. These were accepted in full by the Governors, who ordered that his design be engraved as an aid to fundraising.

Gibbs’s plans were revised over time, but his essential conception remained unaltered. The new hospital was to comprise a central courtyard enclosed by four freestanding ranges. This separation may have been thought to have health benefits, but it also made possible the piecemeal construction of the design as money came to hand. Three of the ranges were identical and housed wards. The fourth—the North Wing—was differentiated architecturally and incorporated the main entrance. Its most important interior was a splendid double-height hall in the proportion of a triple cube (Fig 1), approached up a grand staircase.

Gibbs conceived the hall and the adjacent rooms in the idiom of a City livery hall. The overall conception of the quadrangle, however, followed other institutional projects he must have known. One such was Peckwater Quadrangle at Christ Church, Oxford, begun in 1707 to the designs of Dean Aldrich and likewise engraved for fundraising.

The foundation stone of the North Wing of Barts was laid on June 9, 1730, and its shell was completed by the end of the following year. The original intention was to finish the building in brick and Portland stone, but the quarry owner Ralph Allen persuaded the Governors to use his own Bath stone instead. This proved a disastrous choice in London’s climate and the whole building subsequently had to be refaced, losing its original honey colour. Works to the interior, including the huge decorative plaster ceiling of the hall by John Baptist St Michele, a protégé of the stuccadore Giuseppe Artarti, was also complete, with one important exception, by the spring of 1734.

In February that year, it was reported that the young and ambitious painter born in Smithfield in 1697, William Hogarth, had been selected to paint the main stair to the hall. The decoration of a stair in this manner was a commonplace of grand Baroque houses at the time. He undertook the commission without charge and was appointed a governor of the hospital in return. Rather than paint directly onto the wall, Hogarth worked on canvases that were then hung in place, his themes carefully chosen to suit the hospital.

The first canvas to be completed in 1736 shows Christ, surrounded by figures suffering diverse ailments, healing the paralytic at the Pool of Bethesda. The following year, the adjacent image of the parable of the Good Samaritan tending the wounds of a wounded traveller was also completed. Both scenes are enclosed by extravagant trompe l’oeil frames with the texts of the relevant Biblical passages painted below (Fig 4). There are also pedant images depicting the story of Rahere. The chandelier that lights the stair was a gift of the hospital surgeon John Freke in 1735 and Hogarth and Gibbs both advised on the hang paintings in the hall, which includes three painted fireplace overmantels (Fig 3). Work to the other ranges of the quadrangle continued after Gibbs’s death in 1754, under the direction of the carpenter William Robinson into the 1760s.

Gibbs’s quadrangle has subsequently formed the architectural heart of Barts, around which the hospital has adapted, expanded and developed. In the process, it has itself been threatened with complete destruction, although only its southern range has actually been lost. Such change has partly been driven by increasing demand—in 1835, there were 26,000 inpatients and outpatients per year; today, there are about 300,000—but also advances in medical science. The most recent notable addition to the buildings has been the Maggie’s Centre designed by Steven Holl, which opened in 2017.

Until the 20th century, a great deal of the money for such change came from private benefactions and, since the completion of the hall, the names of the donors have been painted on boards that hang across its walls (an idea surely derived from church donor boards, but taken here to astonishing extremes). Now, once again, in exciting circumstances, names are being added to this roll call.

In 2017, Barts Health NHS Trust, which now runs the hospital, established a new charitable body, Barts Heritage, to help restore the site’s most important historic buildings. To coincide with the anniversary celebrations, the charity instigated the restoration of both the Henry VIII Gatehouse, recently completed, and the North Wing, helped by a generous grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Fundraising for this latter project is in its closing stages, with restoration work planned to begin this month and finish in the summer or autumn of 2025. There will be tours of the buildings during the course of the work. The long-term intention is not merely to put these buildings in physical order, but to make them accessible. In this way, the history of this great institution can contribute actively to the life of the hospital and the wellbeing of both patients and staff today. Rahere, his successors and his countless beneficiaries would surely be proud.

Visit www.bartsheritage.org.uk. This article is indebted to a new history, ‘St Bartholomew’s Hospital. 900 Years’, published by Barts Heritage in partnership with St Bartholomew’s Hospital (£35)

The 900-year-old church tucked away in the gleaming glass and steel towers of the City of London

In 2023, two connected institutions in the heart of London — the church of St Bartholomew-the-Great and St Bartholomew's Hospital in

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill