St Bartholomew-the-Great: A living fossil in the City of London

In 2023, two connected institutions in the heart of London — the church of St Bartholomew-the-Great and St Bartholomew's Hospital in Smithfield, London — celebrate their 900th anniversary. In the first of two articles, John Goodall looks at their foundation story. Photographs by Will Pryce for the Country Life Picture Library.

READ PART TWO OF THIS ARTICLE: 'St Bartholomew’s Hospital: 900 years of service'

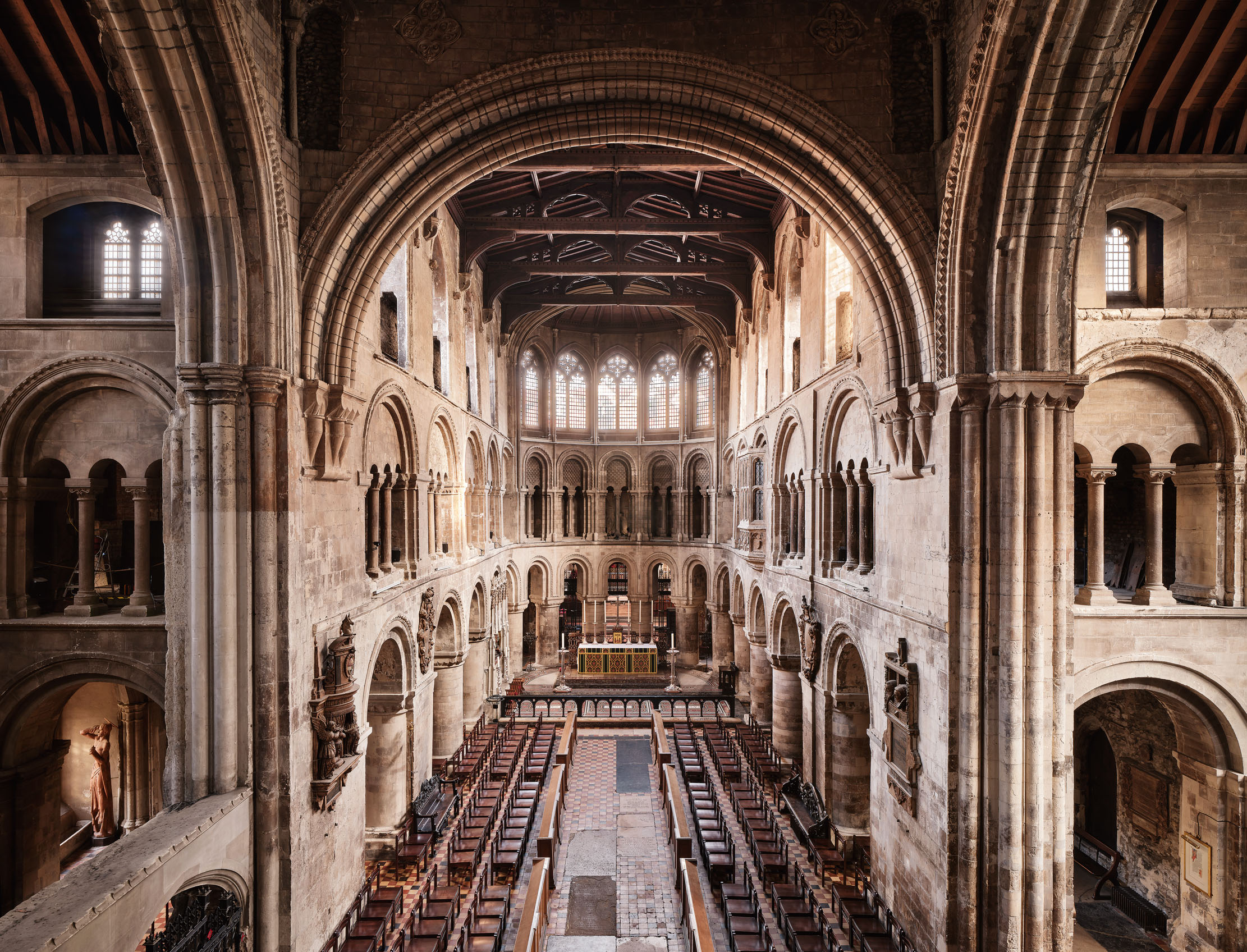

Arriving at St Bartholomew-the-Great always feels like an act of discovery. A single narrow archway separates the bustle of 21st-century Smithfield from a sequestered cemetery. Confronting the visitor across this green space is a spectacular medieval survival that has become fossilised in the fabric of the city: the patched-up remains of a great church begun exactly 900 years ago (Fig 2). It survived the vicissitudes of the Reformation and has served for the past five centuries as a parish church. Such a survival would be remarkable anywhere in the country. Here, in the heart of London, it is nothing short of miraculous.

The story of how this church came to be built is related in a manuscript written by a member of the religious community that formerly served it. The so-called Book of Foundation survives today in both Latin and English copies of about 1400, but seems to be based on a lost, late-12th-century text. This introduces the figure of Rahere, a man of humble birth who, after a carefree youth spent ingratiating himself into the households of the wealthy and powerful (tradition has consequently bestowed on him the character of a jester), underwent a spiritual reform and went on pilgrimage to Rome. There, he fell sick and pledged to found a hospital for the poor if he survived — which he did.

The location and dedication of this promised institution was determined on his return journey, when, in a terrifying dream, a man of ‘great beauty’ and ‘imperial authority’ saved him from falling into a bottomless pit. Having identified himself as the apostle Bartholomew, the figure announced that he had ‘chosen a spot in a suburb of London at Smythfeld where in my name you shall found a church’. Arriving home, Rahere was advised that the proposed site of the church was a royal market, so he petitioned Henry I, who willingly granted the land.

At that time, we are told, Smithfield, which stood just to the north of the city walls, was ‘very foul and like a marsh… the part which was above the water allotted to the gibbet for the hanging of thieves…’. It was on this elevated site of execution that Rahere ‘began to build the church with suitable stone blocks… and the hospital house a little further removed...’. The text specifies that the church was ‘founded’ in March 1123, presumably the date construction began. It also notes local opposition to the project. Rahere was consequently forced to feign idiocy in order to forward his plans and to befriend children and servants, who helped gather the necessary building materials.

The text goes on to explain that a community of ‘clerks’ quickly assembled itself to serve the new foundation. This lived a ‘regular life’ — that is, according to a rule — under the direction of Rahere, who became its governing prior and exercised authority over the hospital. It goes on to relate scores of miracle stories, which it attributes in some way to Rahere’s worthy character, and also offers an account of his death in 1143.

Rahere’s story as narrated in this text conforms in many details to other foundation narratives of the period. That doesn’t mean it’s invented; rather, that some oddities it glosses over deserve careful analysis. Of particular importance is the fact that Rahere established both a priory and a hospital as two linked, but physically distinct entities. This is a very unusual circumstance and it may suggest that the narrative of the Book of Foundation simplifies a more complicated story.

In the early 12th century, the face of the church in England was being reshaped by a powerful reform movement. As part of this, there was a drive to regularise church institutions in order to guarantee the standards of religious life. The most authoritative and long-standing rule — often simply referred to as The Rule — was associated with the figure of St Benedict of Nursia (d.547). There were, however, many clergy who could not — or would not — conform themselves to the communal, but retired monastic life it described.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

An alternative was eventually supplied from a group of letters believed to have been written by another giant figure of the early church, St Augustine of Hippo (d.430). The advice they contained was constituted into the so-called Rule of Saint Augustine, which was introduced to England in the first decade of the 12th century. It was much less prescriptive than the Benedictine rule, which allowed it to be easily adapted to suit a wide variety of purposes, including the governance of hospitals (which were religious institutions), as well as monastic foundations large and small.

That flexibility helps explain the immediate popularity of the rule, but it also makes it very hard to generalise about Augustinian institutions or the activities of the so-called canons or canonesses who served them. The lives of some were very similar to those of Benedictine monks or nuns living communally within the relative isolation of a monastery. Typically, however, Augustinians were closely engaged with the world around them and the life of the laity, for whom they could perform parish duties or undertake the care of the sick.

The Book of Foundation makes no mention of St Augustine, but the newly available rule named after him was clearly perfect for a foundation in a bustling locality immediately outside the walls of London. Presumably by Rahere’s choice, therefore, it was used to govern both the priory and hospital at St Bartholomew’s throughout their subsequent medieval history. From what little we know of other Augustinian foundations, however, there is no obvious parallel for the physical separation of a hospital or infirmary from a parent monastery. At Merton Priory, Surrey, for example, the monastic plan incorporated an unusually large infirmary attached to a secondary cloister, which may have acted as a hospital.

A perfectly plausible alternative narrative, therefore, is that a hospital already existed at Smithfield and that the Bishop of London, a background figure in the foundation story, wanted to regularise it. To achieve this, he might have tried to subsume the hospital within a new priory foundation. If that’s the case, it may be very significant that Prior Rahere was probably one and the same as a namesake prebend of St Paul’s Cathedral and, therefore, well known to the bishop. Such circumstances might explain the separation of the two elements of St Bartholomew’s and, if this move was resented, the poor relations that subsequently subsisted between them. It might also underlie the resistance that Rahere confronted.

However St Bartholomew’s came into existence, its medieval form and evolution are not in doubt. The priory and hospital each came to occupy a walled enclosure, divided by a lane. The former assumed a familiar monastic form, its buildings arranged around a cloister, with a notably ambitious church laid out on a cross-shaped plan.

The surviving eastern arm of the church, which was presumably begun in 1123, possesses a three-storey internal elevation (Fig 6) and terminates behind the high altar in a semi-circular apse (Fig 1). This was enclosed by a vaulted aisle (Fig 3) from which three chapels, now lost, radiated outwards. The internal elevations of the choir were enriched as an afterthought by the insertion of small columns and arches into the middle or triforium storey. Curiously, the masons left some of the decoration of these arches unfinished.

Construction initially seems to have progressed as far as the central crossing (Fig 5), which stood over the canons’ choir stalls. By the 13th century, ongoing work to the Romanesque nave was abandoned and its fabric cannibalised within a two-storey, Gothic design with vaulted aisles.

The archway that today opens onto Smithfields is in fact, a former door to the south-nave aisle interior (Fig 4) and part of the great public façade of the church that formerly overlooked Smithfield market. In about 1300, a new Lady Chapel was built to the east of the church beyond the high altar and, soon afterwards, a new cloister with vaulted walks was erected.

Among the many subsequent medieval alterations to the building, one round of changes to the eastern arm of the church in about 1400 deserves particular mention. As part of these works, probably overseen by the King’s mason Henry Yevele, a parish chapel in the north transept was extended eastwards, parallel to the north choir aisle. At the same time, the Romanesque choir interior was modernised, with tall clerestory windows and a large east window. Finally, a new tomb to the founding figure of Rahere was erected to the north of the high altar. The tomb was, in turn, probably integral with a new high-altar reredos (Fig 7). Given this promotion of Rahere, it’s unlikely to be a coincidence that the surviving copies of the Book of Foundation also date to this period.

St Bartholomew’s was one of several exceptionally wealthy religious foundations with interconnected histories to the north of the City in the late Middle Ages. They include St John’s Priory (Country Life, February 10, 2016) and the Charterhouse. By 1535, it had an income of £693 per annum, which made it one of the wealthiest Augustinian foundations in the kingdom. We will pursue the history of St Bartholomew’s hospital in next week’s issue, but the wealth and the position of the priory in a bustling suburb of London promised an unusual future after the community surrendered its possessions to Henry VIII on October 25, 1539. When the canons left, their precinct — which was already developed with tenements — was established as a new parish, that of St Bartholomew-the-Great, with the choir of the priory as its church. Soon afterwards, in about 1542, the north transept and the priory nave were demolished. These changes were probably directed by the new owner of the monastery, Sir Richard Rich, one of the architects of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He had snapped up this plum property and reconfigured the monastic buildings as a splendid London mansion.

A few years later, however, much of this property was wrested back from Sir Richard by Queen Mary as the home of a new Dominican Friary. That foundation lasted three years, from 1556–59, and it was in this period that the surviving door of the priory nave was overbuilt in timber frame to create the gatehouse familiar to modern visitors. Following the accession of Elizabeth I, Sir Richard bought back the property, but the interruption in his ownership seems to have set the buildings on a new path of further redevelopment and eventual absorption within the intensifying urban development around Smithfield. The area was initially wealthy and genteel, as the fine funerary monuments in the church testify, but, by the 18th century, it was increasingly impoverished.

It took the antiquarian interest of the 19th century to reverse the increasing dilapidation of the church and create the building we see today. The full story of fundraising and incremental changes would furnish another article and it is outlined in the recent anniversary volume of essays 900 Years of St Bartholomew the Great edited by Charlotte Gauthier, to which this article is indebted. Crucial to the process was the architect Sir Aston Webb, a figure most familiar today as the creator of the façade to Buckingham Palace. His family was closely associated with the church and his brother, Alfred, wrote the voluminous standard history of the building. Restoration extended both to the east walk of the cloister and the Lady Chapel. Through their work, and the ongoing life of the parish, the modern visitor is brought face to face with the startling depth and complexity of London’s history.

For more information, visit www.greatstbarts.com

Acknowledgements: David Robinson and Jeremy Haselock

The architecture of the National Gallery, 'one of the defining landmarks of London'

In the wake of the re-opening of museums, John Goodall looks at the architecture of the National Gallery in London

Westminster Abbey: 1,000 years of coronations, from King Harold and William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II and Charles III

The setting of Charles III’s crowning in Westminster Abbey in London lends grandeur and history to this great ceremony. John

The Reform Club: Inside 'the most magnificent club in London', almost unchanged since the days of Phileas Fogg

The Reform Club was made famous by Jules Verne as the home-from-home of Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty

London has never been this quiet in 2,000 years — here's what it looks like, and what we can learn

In all of its 2,000-year history, it seems unlikely that the City of London has ever stood so silent as

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life