Saints alive: How St Albans Cathedral has entered the 21st century in vibrant style, thanks to sculptors, artisans and dazzling colour projections

The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans is one of the oldest churches in Britain — and quite possibly the very oldest — but no building survives through hundreds of generations without change. John Goodall examines some of the recent changes made to highlight the saints associated with this ancient church. Photographs by Paul Highnam and John Goodall for Country Life.

On June 25, 1178, a grand procession conveyed a collection of bones exhumed from a burial mound at Redbourn, Hertfordshire, to the great Benedictine Abbey of St Albans three miles away. Among them were supposedly the remains of a cleric who had been saved from persecution by the bravery of the abbey’s eponymous saint in the late Roman period.

As described in the previous article, early accounts of Alban’s execution outside the walls of Verulamium, possibly in 304BC, offer no record of the cleric’s name or subsequent story. In 1135, he became Amphibalus — or ‘cloak’ — the word borrowed from an item of his clothing mentioned in a 6th-century narrative of Alban’s martyrdom. An exemplary restoration project has now given Amphibalus physical presence within this church once again.

[Read more: The history of St Alban — and how he inspired the creation of St Albans Cathedral]

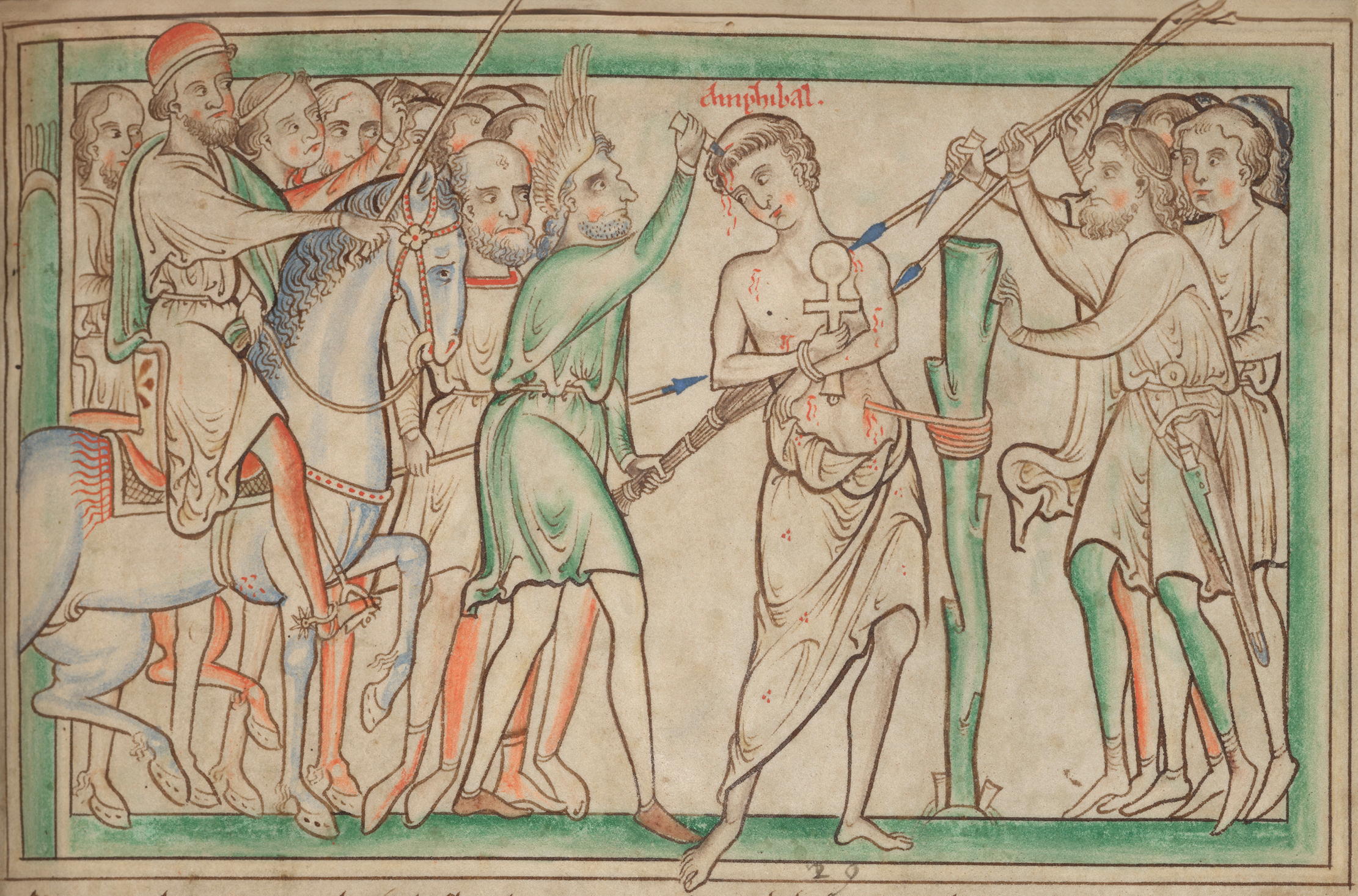

The procession of 1178 followed hard on the feast of Alban’s martyrdom on June 22. It was also connected to an account of the life of St Alban — masquerading as a Latin translation of an ancient British text — recently composed by a member of the monastic community called William. According to this, Amphibalus fled to Wales and was followed by 999 citizens of Verulamium who had been converted to Christianity by his preaching. The whole group was pursued and massacred, but Amphibalus was bound in chains and brought back to the city. There, he was executed by being forced to walk around a post to which his intestines had been nailed (Fig 1). A further butchery of Christians followed and, in the confusion, Amphibalus’s corpse was hidden, ‘to be brought to light at some time or other — by divine action as we may believe’.

William’s words read as preparation for precisely that discovery. The likelihood is that the bones conveyed to St Albans Abbey in 1178 actually came from an Anglo-Saxon burial. These often contain multiple burials with weapons, which would explain why Amphibalus’s remains were found — according to the 13th-century historian of St Albans, Matthew Paris — with two iron knives, ‘one in the skull another in the heart’, and 10 companions. Whatever the case, in 1186, the relics were gathered together in a casket overlaid in silver and gold and bearing images of Amphibalus’s martyrdom. This was placed to the north of Alban’s shrine behind the high altar.

Probably in 1222, the casket was moved to the nave altar in front of the rood screen, where it was enclosed by an iron railing and elevated on a slab supported by columns, a conventional arrangement for shrines in this period. The collapse of the south nave aisle in 1323 damaged this structure and the rood screen, but the relic casket miraculously survived and was moved back to the area of Alban’s shrine behind the high altar. Then, probably in the 1350s, the sacrist of the abbey, Ralph Witechurch, commissioned a new and elaborate stone pedestal base for it.

After the manner of St Alban’s shrine, which had been sumptuously renewed in Purbeck marble by 1308 (and was itself restored to its present condition in the early 1990s), the pedestal was conceived as a miniature work of architecture. There were recesses on each face of the structure for pilgrims to kneel in close proximity to the relics above and panels of patterned decoration. These included the sacrist’s initials and the name Amphibalus. The pedestal cost £8 18s 10d and was on the central axis of the church between St Alban’s chapel and the eastern Lady Chapel. On the ceiling above it was a large depiction of the Assumption of the Virgin.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Here it remained until the Reformation, when the bones were discarded and the pedestal, together with that of St Alban’s shrine, was smashed into fragments. Some were used to build an internal wall that created a dividing corridor between the church and the Lady Chapel (which became a grammar school). All this was forgotten until 1872, when the wall was dismantled and the shrine fragments discovered. The architect responsible, George Gilbert Scott, worked with J. T. Micklethwaite to reassemble the thousands of pieces they found, with attention understandably focused on the Purbeck-marble shrine pedestal of St Alban. That of Amphibalus was less completely reconstructed and was eventually left as a rather unsightly mass of masonry pieced out with industrial brick and pushed against a radiator in the north choir aisle.

English medieval shrine bases are a rarity and the substantial remains of only eight comparable examples are known today, including that of Birinus at Dorchester-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, and Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey in London. A symposium on the pedestal of Amphibalus in 2004 recommended that it be restored and this vision was taken up by the then Dean, the Very Revd Dr Jeffrey John. He described the shrine base in a report of 2015 as notable ‘not merely as an important medieval artefact but also as a contemporary source of inspiration and focus of devotion… [Amphibalus] is a symbol, not only of martyrdom in general, but of specific Christian themes of witness, mission, priesthood, prayerfulness, personal example, education and catechesis — for all of which his shrine could be a focus’.

The ensuing restoration, by Skillingtons, was planned and informed by a number of specialists, including the cathedral architects Richard Griffiths and Kelley Christ, archaeologists Martin Biddle and Jackie Hall and architectural historians Richard K. Morris and Linda Monckton. In anticipation of the work, there was a search for additional pieces of the pedestal that had come to light since its first restoration. Traces of colour on the masonry, including red, green, blue, black, purple and gilding, were examined by the Perry Lithgow Partnership. The Cathedral Fabric Advisory Committee, of which the writer was a member, supported the initiative.

The first challenge, in 2019, was to disassemble the existing pedestal, the fragments of which were held together with cement mortar and iron cramps. Large missing elements of the structure were pieced out with newly carved masonry. The Totternhoe Stone of the original is no longer quarried, but some old blocks were fortuitously located in a building yard in Cambridge. Damaged or fragmentary pieces, including the side panels and sculpture, were built up in carefully matched lime mortars. One particular problem was the loss of all the bases and capitals, which meant that an informed guess had to be made as to the diameter of the new Purbeck shafts that flank the recesses.

Work to the reconstruction of the shrine in the Chapel of Four Tapers at the east end of the south aisle began in 2020 on a low plinth. This date appears in one of the new panels and, in reference to the pandemic, one of the newly carved grotesques wears a mask (Fig 4). The structure is held together with stainless-steel dowels set in polyester. To complete the structure, the Royal School of Needlework was commissioned to make a canopy for the pedestal that would stand in place of the long-lost casket (Fig 2). At the same time, the artist Peter Murphy was commissioned to paint a series of icons representing the story of Amphibalus’s martyrdom, which fill the surrounding chapel arcade (Fig 3).

The shrine’s reconstruction is one of four recent changes to the interior of the church. The other is the installation within the rood screen of seven statues of Christian martyrs — ancient as well as modern and from different denominations — by the sculptor Rory Young (Fig 6). These figures were developed over five years and consecrated in 2015. The rood screen was rebuilt in its present form following the collapse of the south-nave aisle in 1323 and its central altar and statuary were stripped away at the Reformation. In the present configuration of the church, the screen serves as the backdrop to the nave altar. Alban himself stands in the centre holding his executioner’s sword and a distinctive cross. A cross of this kind — probably a Coptic one acquired as a relic — is first shown in the 13th-century illustrations of the saint’s life drawn by Paris.

To Alban’s left is Amphibalus and to his right George Tankerfield, a cook burnt to death outside the west front of the church for his Protestant faith in 1555. Also shown are Alban Roe, a Benedictine monk and priest who was imprisoned in the abbey gatehouse and hung, drawn and quartered at Smithfield in 1642. To the sides are modern martyrs of different denominations: Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was shot in El Salvador in 1980; Elizabeth Romanova of the Russian royal family, who became an abbess and was murdered in 1918 and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran pastor and Nazi dissenter killed in Flossenburg concentration camp in 1945.

Following the completion of the rood-screen sculpture, another project was begun in 2015 to help interpret the medieval wall paintings on the piers of the nave (Fig 7). These were originally associated with the parish church that was attached to the north side of the abbey until the Reformation. With the help of art historian Michael Michael and an illustrator from the British museum, Craig Williams, the original details of these fragmentary schemes were reconstructed. Two technology companies, Fusion and Figment, turned the reconstructions into projections that enable visitors to understand the form of the original paintings more clearly (Fig 8). The success of this undertaking has informed another illumination scheme, which focuses on one of the most remarkable medieval furnishings in the church.

In the later 15th century, Abbot William Wallingford paid for a new reredos behind the high altar. This took the form of a huge screen of sculpture, a treatment popular in England from the 14th century. The imagery it contained was stripped out and destroyed at the Reformation. In 1883, however, soon after the elevation of St Albans to the status of a cathedral, the banker Henry Hucks Gibbs, later Lord Aldenham, contemplated renewing the reredos. The lawyer and amateur architect Sir Edmund Beckett, later Lord Grimthorpe, however, who had assumed control of the restoration of the whole building in the 1870s, fiercely opposed the plan, although he failed to prevent new figures for the screen being commissioned from the prolific ecclesiastical sculptor Harry Hems.

Most were installed by 1890, the same year Gibbs and Beckett entered into a nine-year legal battle — which the latter ultimately lost — over the reinstatement of a central crucifix in the reredos. Today, it is the quantity of Hems’s sculpture, rather than its quality, that most impresses. The one notable element of the restored screen is the figure of the resurrected Christ above the altar by Alfred Gilbert. It inhabits a different aesthetic world from the remainder of the screen sculpture and incorporates mother of pearl and crystal. Using a scan of the whole reredos and in partnership with the agency Hogarth, colour can now be projected onto the whole composition of the screen (Fig 5). It is another way that the cathedral has sought to animate the images of saints that both lie at the foundation of its history and preside over its modern life.

Visit www.stalbans.org

A walk around St Albans and its cathedral — a 'welcoming place, and proud of it'

Fiona Reynolds explores the ancient city of St Albans to discover how its cathedral connects with the people and geography

The tale of St Alban: An abbey, a Cathedral, and a martyr so holy that 'his executioner’s eyes popped out of his head'

A church built for Britain’s first known Christian martyr developed into The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans, Hertfordshire.

350 years in the architectural evolution of Lincoln's Inn, from 1672 to 2022: 'Self-consciously Gothic, constitutional and English'

In the second of two articles, John Goodall examines the architectural development of Lincoln’s Inn from the late 17th century

Westminster Abbey: 1,000 years of coronations, from King Harold and William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II and Charles III

The setting of Charles III’s crowning in Westminster Abbey in London lends grandeur and history to this great ceremony. John

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel