The tale of St Alban: An abbey, a Cathedral, and a martyr so holy that 'his executioner’s eyes popped out of his head'

A church built for Britain’s first known Christian martyr developed into The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans, Hertfordshire. John Goodall tells the tale of the saint and the building he inspired; photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

The Cathedral of St Albans in Hertfordshire has a claim to be the most ancient of all Britain’s churches. The story of the settlement it serves can be traced back archaeologically into the Iron Age. By the early 1st century AD, it had become an important centre of the Catuvellauni tribe and then developed into a Roman municipium, Verulamium, on Watling Street. Verulamium’s late-3rd-century walls enclosed about 200 acres of land on the west bank of the River Ver, an area only exceeded by Londinium and Camulodunum (now Colchester). To the east, on the opposite side of the river, was a cemetery and, next to it, a hill occupied by a temple. On the slope beneath the temple, excavation has revealed votive pits with various deposits — including a flayed human skull — suggestive of a cult associated with heads.

Verulamium was not entirely abandoned following the withdrawal of the Roman legions in 409, but became instead the focus of a Christian cult to a martyr: St Alban.

We know of his history by circuitous means. In 429, Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, was sent to Britain by the Pope to combat the Pelagian heresy. On the Bishop’s return to Gaul, he built a basilica in Auxerre dedicated to a certain Alban and is thought to have hung texts describing his martyrdom on its walls. These texts — known from manuscript copies — were probably the fundamental source of all subsequent stories associated with the saint and, although long lost, their account of his martyrdom can be summarised as follows.

In a time of persecution at some unspecified place, a man called Alban gave sanctuary to an unnamed cleric. Alban, a pagan, put on the man’s cloak, assumed his identity and was condemned to death as Christian on June 22. Between the walled city, where he was tried, and the arena where he was to be executed, there was a bridge choked with onlookers. To avoid it, Alban stepped into the river beneath and the waters miraculously subsided to let him pass. In the arena, Alban’s first executioner threw away his sword and offered to be martyred in the prisoner’s place. As a replacement was sought, Alban climbed a flower-covered hill nearby. A spring bubbled up in answer to his request for a drink. When he was eventually beheaded, his executioner’s eyes popped out of his head.

Apart from the arena, the topography of the city described in the martyrdom broadly corresponds with what is known of Verulamium, with its walls — suggesting one possible dating of the narrative to the persecution of the Emperor Diocletian in 304 — river and hill. It’s possible, also, that the earlier head cult somehow informed the narrative of Alban’s decapitation or the fate of his executioner. Early authority for the association of the martyr and Verulamium comes from the 6th-century historian Gildas. This is a connection further reaffirmed in 731 by Bede in The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, who adds that ‘a beautiful church worthy of his martyrdom was built, where sick folks are healed and miracles regularly take place to this day’.

That church certainly existed by the early 5th century because, according to the Auxerre texts, it was visited by Bishop Germanus. There, as Bede also relates, he opened the saint’s tomb to insert more relics and remove soil stained by the martyr’s blood. Constructing churches over the graves of saints is a phenomenon paralleled across the later Roman Empire. In the case of St Albans, it would suggest that the church today, which stands outside the walls of Verulamium on the site of a Roman cemetery, is a direct successor to this building. Incredibly, therefore, the shrine seen by the visitor behind the high altar today could actually stand on — or close to (the burial place was supposedly identified in the Middle Ages) — the spot where Alban was buried 17 centuries ago.

It was to serve this church — or a successor building — that, in about 793, Offa, King of Mercia, founded a monastery here. A settlement grew up beside it and this was formally enlarged in about 950 by one of its abbots, Wulsin. Verulamium, meanwhile, was left to ruin. Soon after this, in a charter of King Æthelred Alban is described as the ‘protomartyr’ — or first martyr — of the English. He has enjoyed the title ever since, although, as early as the 15th century, it was correctly noted that he actually long predated the English as a people.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1070, after the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror made the abbot of Saint-Étienne at Caen, Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. Lanfranc, a formidable scholar, reformer and builder, in turn appointed his nephew, Paul, Abbot of St Albans in 1077. According to the chronicle compiled in the abbey, Paul began rebuilding the church ‘from the stones and tiles of the old city of Verulamium, and with the wooden material which he found collected and reserved by his predecessors’. Evidently, the existing building had long been deemed ripe for redevelopment.

Whether Abbot Paul completely rebuilt the church or subsumed a fragment of the earlier building within his new work has recently become a matter of scholarly debate. Whatever the case, at the moment of its conception, the new abbey church was — briefly — the largest in the kingdom and closely resembled in plan the churches begun by Lanfranc both at Caen, France, in about 1066 and at Canterbury Cathedral in Kent after 1070. It was designed by a certain Robert, who was described as excelling all the masons of his time.

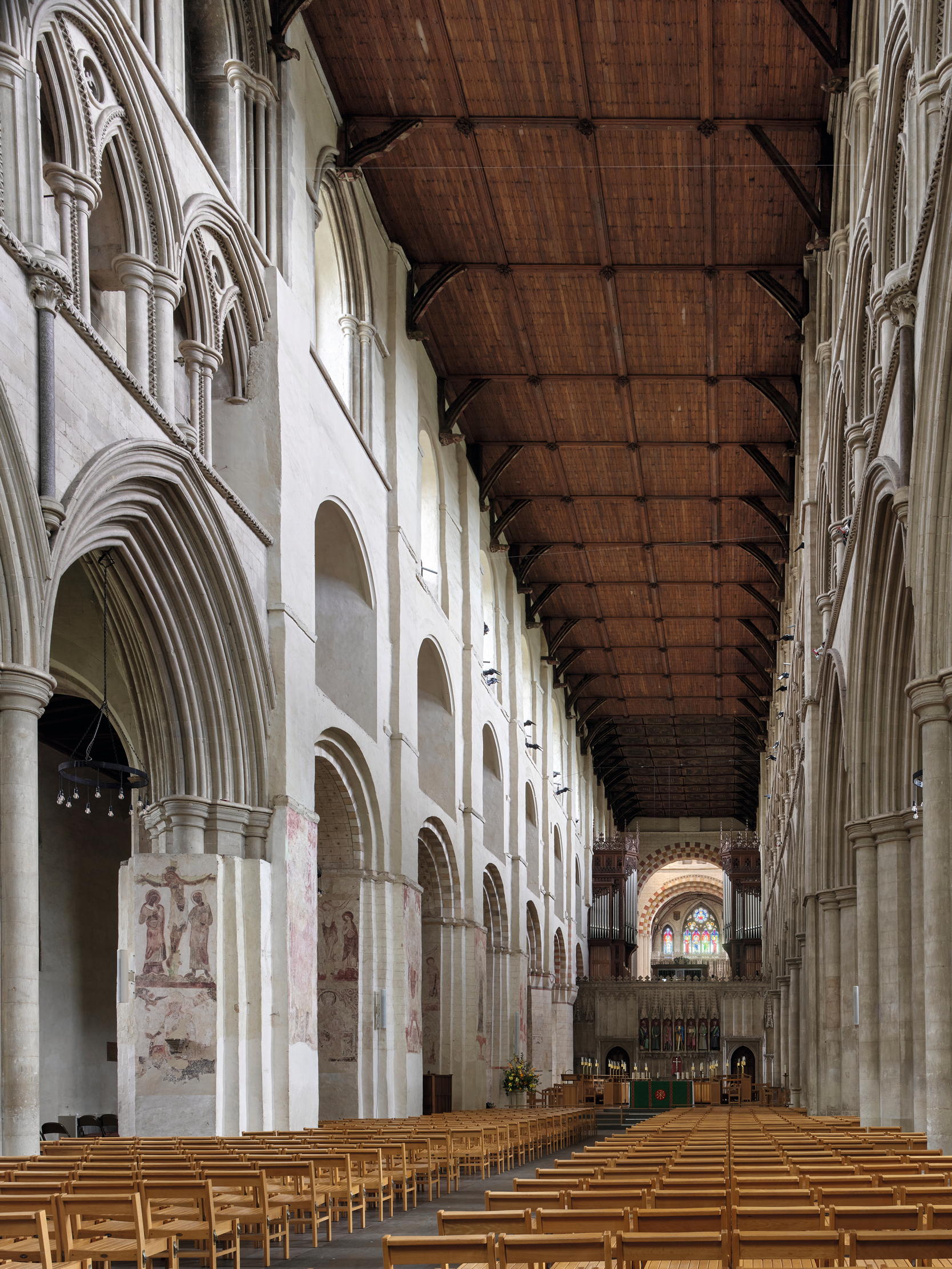

Robert’s church was laid out in a cross-shape with a central tower over the intersection of its four arms. The eastern arm containing the high altar was unusually long and probably vaulted in stone, a mark of exceptional architectural ambition. It terminated in a semi-circular apse. Two subsidiary apses opened off the arms or transepts of the building, which — undivided by aisles — were oddly spacious. What were they for? The leviathan nave was roofed in timber.

The extent of the surviving 11th-century fabric at St Albans is remarkable. It includes the earliest surviving crossing tower (Fig 1) and full internal elevation of a great post-Conquest church in England. The use of recycled Roman materials almost certainly explains the rugged character of the design (Fig 2), the details articulated by recessions of plane rather than carved mouldings. Brick and stone were used in places to create contrasts of colour and decorative patterns. Some Anglo-Saxon masonry, including turned shafts, was also recycled. The shafts presumably came from the earlier church.

In the century after the Conquest, St Albans grew into one of the wealthiest abbeys in England, with dependent monasteries spread across the kingdom, including Wymondham and Binham in Norfolk, Wallingford in Oxfordshire and Tynemouth in Northumberland. The latter, part castle and part monastery, became a place of exile for awkward members of the community. St Albans was also declared the premier abbey of the kingdom by the only English pope, Adrian IV (d.1159), the son of a priest and monk of the abbey.

Over the same period, in common with other major monastic foundations, the abbey acquired a new saint. The narrative of Alban’s martyrdom frustratingly omitted the name and fate of the cleric he protected, so, in 1135, the sensationalist historian of Britain’s legendary past, Geoffrey of Monmouth, translated the cloak — or amphibalus — of Gildas’ narrative into his person. St ‘Cloak’ or Amphibalus was then provided with his own martyrdom story and his body discovered at nearby Redbourn. It was conveyed to the Abbey on June 25, 1178.

In 1195, the newly appointed Abbot of St Albans, John de Cella, appointed the mason, Hugh de Goldcliffe, to extend the nave and add to it a massive west front with three porches (Fig 6) and flanking towers. The project, which shows a technical knowledge of contemporary work at Lincoln Cathedral, made profuse use of polished Purbeck shafts. It proved a disaster, however. Hugh was dismissed in 1197 after a collapse and the whole completed in simplified form without towers or vaults by 1230. The great historian of the abbey, the 13th-century monk Matthew Paris, noted Hugh’s ‘great reputation’, but described him as ‘a deceitful and unreliable man’.

In 1257, alarming cracks appeared in the fabric of the eastern arm, which was, in turn, remodelled (Fig 3). Work progressed westward from the crossing tower with the solid lower Romanesque walls encased and raised with a new clerestory of brick, an unusual material in this period. The area of St Alban’s shrine beyond the high altar, meanwhile, was boxed in by spectacularly rich arcades, now largely obscured (Fig 9). The whole arm was closed by a timber vault between 1273 and 1299. This originally incorporated liernes — ribs that do not connect with the walls — a revolutionary detail of great future importance in English architectural design. Work concluded with the addition of a Lady Chapel, the walls of which stood completed by 1308. The inclusion of sculpture in the window tracery of the Lady Chapel suggests a connection with the exceptionally ambitious chapel of Merton College, Oxford, and the buildings associated with it.

In tandem with these works, the shrines of Alban and Amphibalus were renewed, respectively in 1308 and the 1350s. During the interim, however, in 1323, part of the south side of the Romanesque nave collapsed. The repair by the mason Henry Wy creates an unusual patchwork, in which the two sides of the interior appear out of step (Fig 8). One striking feature of the nave are the 13th-century figures of saints painted on the Romanesque piers. These formerly related to altars and a parish church that once adjoined the north side of the building.

During the late Middle Ages, the eastern arm was gradually enclosed by new monuments of exceptional quality and individual interest. They include the tomb of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (d.1447), one of Henry V’s brothers and the founder of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, probably designed by the master mason of Westminster Abbey, John Thirsk; the high altar reredos of 1480–84 built at a cost of 1,100 marks; and the chantry chapel of Abbot Ramridge, built in about 1515 (Fig 7). There is also a timber watching loft presiding over the shrine of St Alban.

St Albans had enjoyed a princely annual income of £2,100, the fourth largest of any religious house in the kingdom, yet, on December 5, 1539, a community of about 40 monks surrendered their ancient monastery to Henry VIII. The bulk of the monastic buildings were almost immediately swept away, although the great 14th-century gatehouse was preserved as a prison. In 1551, the town purchased the abbey as a vast parish church from the Crown for £400. The last abbot — an imposed appointment — also purchased the Lady Chapel, where he went on to run a grammar school. This was separated from the body of the church by a public passage and wall constructed with architectural spoil, including the smashed fragments of the shrines of St Alban and Amphibalus.

The town was proud enough of the church to preserve it for the next three centuries, but not rich enough to transform it. To a quite exceptional degree, therefore, its medieval fittings, as well as an astonishing wealth of wall paintings, survived here (Fig 4). The building gradually deteriorated, however, and a rolling programme of restoration began in the 19th century. Sir George Gilbert Scott became involved in 1856 and, during the course of his work in 1872, rediscovered the immured remains of the shrines of Alban and Amphibalus. Both were painstakingly reassembled, the former from more than 2,000 fragments. Alban’s shrine was again renewed in 1993 and occupies its historic position behind the high altar (Fig 5).

The Abbey became a cathedral in 1877, the year before Scott died. Thereafter, the lawyer Sir Edmund Beckett, later Lord Grimthorpe, took charge of the restoration and poured money into the fabric. Wealthy and abrasive, he was, by his own description, ‘the only architect with whom I have never quarrelled’. It is a reflection of the mixed contemporary reaction to his work that ‘grimthorpe’ entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 1890 as a pejorative term for a lavish, but inept restoration.

In 1979–82, the architect Sir William Whitfield undertook the creation of new facilities for the cathedral on the site of the former chapter house. It was a characteristically brilliant work of contextual architecture constructed of specially made Roman-style bricks. This building was extensively reworked in 2017–19 by Simpson and Brown to create a new entrance and visitor facilities. In the meantime, the cathedral has undertaken a series of notable initiatives to improve the presentation and decoration of the church, including the restoration of the shrine of St Amphibalus, as will be discussed in next week’s article.

Visit www.stalbanscathedral.org

A walk around St Albans and its cathedral — a 'welcoming place, and proud of it'

Fiona Reynolds explores the ancient city of St Albans to discover how its cathedral connects with the people and geography

Westminster Abbey: 1,000 years of coronations, from King Harold and William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II and Charles III

The setting of Charles III’s crowning in Westminster Abbey in London lends grandeur and history to this great ceremony. John

Credit: Savills

An astonishing home in St Albans that's equal parts Roman villa, Japanese temple and medieval cloisters

Fluid spaces, thoughtful feng shui and peaceful grounds make Abbey Orchard House in St Albans the ultimate zen escape.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.