Sir Edwin Lutyens: Britain's greatest architect?

This year is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Edwin Lutyens, one of Britain’s most celebrated architects. John Goodall revisits his life, personality and work.

On September 29, 1896, Edwin Lutyens wrote to Lady Emily Lytton, his future wife, describing a casket he intended to make for her as a token of his devotion. It would contain Marcus – a little brass pipe stopper – and a small Bible. Between them would be sandwiched compartments for an anchor and a heart, emblems of hope and love, a miniature book with a poem, sealed shut, and a design for a house.

When she accepted the gift, Lady Emily additionally requested it contain a crucifix and offered an inscription to which – on the exquisitely finished casket – Lutyens pointedly added: ‘As Faith wills, so Fate fulfils.’ It might be read as a commentary on his extraordinary career.

Lutyens was born in 1869, the 10th of 13 surviving children of the soldier and painter Capt Charles Lutyens and his Irish wife, Mary Theresa née Gallwey. He was not a healthy child and it was this, he later maintained, ‘that afforded me time to think: and… to teach myself, for my enjoyment, to use my eyes instead of my feet’.

When the family acquired a Surrey house at Thursley in 1876, he explored the surrounding countryside in what remained a relatively undeveloped area by foot and bicycle. In the process, he learnt about local buildings and their materials.

To record what he saw, Lutyens invented a technique of drawing using soap cut to an edge on a sheet of glass. This allowed him to trace details from life and understand both perspective and three-dimensional form. By degrees, he developed an extra-ordinary ability to commit architecture to memory without drawing.

In addition, his Surrey ramblings regularly took him to a builder’s yard and carpenter’s workshop, where he learnt about the practicalities of building and joinery. They also introduced him to fishing, a lifelong pastime.

In 1888, Lutyens became a pupil in the London architectural office of Ernest George and Peto. It was here that he befriended Herbert Baker, who would later become Britain’s other outstanding Imperial architect.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A year later, on the back of a commission from a family friend to design Crooksbury House at Tilford near Farnham, Surrey, he set up his own practice. It was in this same year that he met the mentor, friend and advocate who would transform his career: garden designer Gertrude Jekyll.

She saw through the shy exterior of this young man with striking blue eyes and unusually long legs. Between 1895 and 1897, in close collaboration with Jekyll, he designed a new house for her in the existing garden at Munstead Wood, Surrey. Built in the vernacular Surrey style, it was much admired and Jekyll herself played a crucial role in introducing her young protégé to new clients.

Among them was Edward Hudson, the founder, in 1897, of Country Life. The magazine – with its interest in the Arts-and-Crafts Movement and the Picturesque – promoted Lutyens’s work and, particularly through the work of its Architectural Editor, Christopher Hussey, played a crucial role in shaping the architect’s reputation.

It was also in 1897 that 28-year-old Lutyens married the recipient of his casket, Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton, who was four years his junior and a daughter of the diplomat, poet and former Viceroy of India the 1st Earl of Lytton. Their marriage, documented in thousands of letters, would prove unconventional and, at times, strained, but it held.

Both were strong-willed and independently minded. To complicate matters further, Lady Emily had little interest in the social duties of an architect’s wife, instead campaigning actively for women’s and political causes.

The newlywed couple moved into 29, Bloomsbury Square, London. The ground floor of this large Georgian house became his office. Money was tight and Lutyens looked eagerly for work. Fortunately for him, the train and motorcar had created an unprecedented demand for houses in the countryside around London. These were essentially villa retreats for the wealthy, furnished with every modern luxury.

The taste of the moment, shaped by William Morris and the Arts-and-Crafts Movement, was for houses connected to their landscape, constructed with local materials and built with reference to vernacular architecture.

It was a market that Lutyens was perfectly qualified to satisfy and Country Life eagerly promoted his brilliant creations (although – as the late Gavin Stamp pointed out – it pointedly ignored his brief flirtation with Art Deco). His office grew busy.

According to Oswald Milne, an employee in 1902–05, Lutyens ‘was a great worker… he stood working at his drawing-board in the front office – I do not remember him ever sitting down – legs apart and usually smoking a pipe. He spoke somewhat incoherently; he never explained himself; his wonderful fund of ideas and invention were expressed not in speech, but at the end of his pencil’.

Lutyens delighted in the absurd and had a childish sense of humour. He particularly, therefore, enjoyed the company of children. ‘Are you afraid of electric shocks? Well you see this matchbox with two matches sticking out of it. Take hold of one in each hand and then – very carefully – lift a foot… do you feel it? … your leg being pulled?’

Anecdotes abound of his using a pencil and a pocket pad known as a virgin (or any sheet of paper to hand) to turn over and articulate ideas or amuse.

His personality won the affection of his office as well as his clients. The latter frequently returned to him, despite the fact that his buildings were expensive. Many were impressed by his architectural vision and his single-minded determination to realise it. In conversation, this earnest intent expressed itself in epigrammatic dictums and insights.

Meanwhile, Hudson had emerged as an admiring friend and client, commissioning a house in 1899, The Deanery in Sonning, Berkshire, a holiday home at Lindisfarne Castle in 1901 and Covent Garden offices for the magazine itself in 1904.

Hudson was formidably connected socially and politically (partly through his publisher, George Riddell). According to Hussey, both men ‘were largely self-educated, with an instinctive appreciation of beauty; both were inarticulate… Lutyens in addition benefitted from Hudson’s shrewd common sense and business acumen. Whilst he addressed him as Huddy, the latter got no further than Lutyens throughout thirty-six years’.

In 1900 and 1911, Lutyens secured two prestigious commissions via Jekyll’s brother to design British international pavilions for exhibitions at Paris and Rome; the latter became the British School at Rome. They were patriotically inspired by the Hall at Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire, and St Paul’s, London.

By 1908, Lutyens’s marriage had produced five children. It was about to be complicated, however, by Lady Emily’s introduction to Theosophy. Lutyens was sympathetic to this fashionable mystical movement, but its effect on his wife – who became a vegetarian, left his marriage bed and adulated the Brahmin Krishnamurti, its teenage figurehead – proved to be a strain on their relations.

At the same time, Lutyens himself became increasingly fascinated by Classicism. He referred to it as ‘the big game’, a reference both to its monumentality and formality. Lutyens might reasonably never have had the chance to explore this idiom (and would per-haps have remained no more than the brilliant designer of luxury villas) had not fate now contrived to conform itself to his desires.

At the Delhi Durbar of 1911, it was announced that a new Imperial capital would be created in India. The planned city of New Delhi was an architectural endeavour on the grandest scale. Lutyens was invited to join the planning commission of the new city and took responsibility for its centrepiece: Viceroy’s House.

It is a compelling architectural expression of Imperial authoritarianism – a gigantic Classical building suffused with ideas drawn from Indian architecture (about which the architect was unaccountably dismissive) set in a Mughal-inspired garden.

The construction of New Delhi continued throughout the First World War and brought with it many difficulties, including a bitter quarrel with Baker over the approach to Viceroy’s House. Lutyens wittily described his defeat on this point in 1916 as his Bakerloo.

Soon afterwards, Lady Emily took up the cause of home rule for India and held a meeting in support of it in Bedford Square. The consequent strain in relations saw Lutyens spending much time with Lady Sackville, the chatelaine of Knole in Kent. They called each other NcNed and McSack, but their correspondence has been lost.

At this time, the financial difficulties that plagued Lutyens for much of his life brought about the sale of Bedford Square. His office eventually moved to Queen Anne’s Gate, a few doors away from Hudson’s London house.

Lutyens, meanwhile, travelled unceasingly. He had a knack of acquiring remarkable travelling companions and was fortunate to evade the dangers of war.

In 1917, Lutyens was invited to join the Imperial War Graves Commission, the body charged with responding to the sheer scale of human loss brought about by the First World War. He played a crucial role in shaping the form of British cemeteries, arguing in particular for non-denominational remembrance and the creation of headstones that made no differentiation between the dead of different ranks.

Quite as important, from 1917, the architect also began to plan monuments to the fallen. These he designed in an elemental Classical style in which recessions of plane, infinitesimally curved lines and the bowing of surfaces lend movement and energy to the whole. Their inscription was also a subject he thought about intensively.

Among these monuments were the Stones of Remembrance that were designed by Lutyens for each cemetery, to commemorate ‘those of all faiths and none’, as well as such individualistic creations as the Cenotaph in Whitehall, India Gate in New Delhi and the Monument to the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval in France.

Thanks to this work, Lutyens became a household name, his work touching the consciousness – and articulating the grief – of people from every walk of life.

In 1918, when these memorials were still in planning or prospect, Lutyens was awarded a knighthood. The honour, a rarity amongst architects, prefigured his celebrity in the 1920s. He usually socialised alone; Lady Emily, with whom relations eventually improved, asserted that her absence made her the most popular wife in London.

As the architectural historian John Summerson rather acidly observed: ‘You rarely see him but in the company of a pack of fans, sniggering at his cracks and wondering what the great Lut will say or do next. Bores all over the Empire hoard his doodles, do their damndest to collect and recollect some encounter, some passage of wit, wherein they stood irradiated for a moment in the sunshine of authentic Genius.’

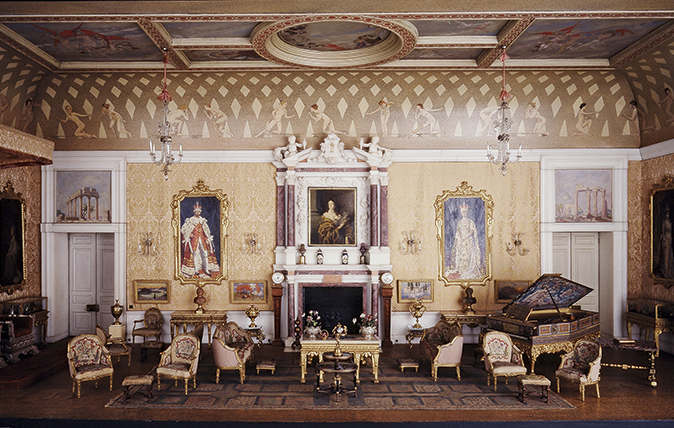

One strange product of this social whirl – the fruits of a dinner-party discussion in 1921 – was an astonishing dolls’ house presented to Queen Mary.

Throughout the 1920s, the construction of New Delhi and numerous war memorials kept Lutyens busy. He continued work as a house designer, although on a reduced scale. Some projects, such as Castle Drogo, Devon, and Ashby St Ledgers, Northampton-shire, ran on as hangovers from pre-war days. Others, such as the ambitious Gled-stone Hall, North Yorkshire, begun in 1923, seem today like Edwardian buildings transposed into a changed world.

Lutyens increasingly turned his hand to office building, notably for the Midland Bank. Among his Government commissions was a new British Embassy in Washington DC.

New Delhi was officially opened in 1931, only 16 years before Indian independence. Hudson, who attended the occasion, held back his tears of admiration and observed: ‘Poor old Christopher Wren could never have done this!’

The 1930s witnessed the start of work to what might have been Lutyens’s greatest building, a new Catholic cathedral in Liver-pool (‘I wish it had been model dwellings,’ observed Lady Emily disdainfully). The cathedral was commissioned in 1929 and Lutyens imagined its completion would necessarily wait two centuries. In the event, it was abandoned in the 1960s, when only its monumental crypt stood finished.

Rightly or wrongly, Lutyens would almost certainly have hated the church now raised above it, not least because, in later life – and as president of the Royal Academy – he was such an articulate critic of Modernism.

Lutyens died on January 1, 1944, by which time, he was undoubtedly one of the most prolific architects in British history. In his Classical mode particularly, he succeeded in creating an architecture that articulated the two overriding preoccupations of the Britain he knew: war and empire.

In so doing, he directly touched the lives of untold numbers of people. It is hard to think of any architect who can claim as much. Whether or not he is Britain’s greatest ever architect, there can be no doubt that he is in the running for the prize.

The house where they took a risk on a young architect named Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Lutyens was without doubt one of Britain's finest-ever architects – but it was thanks to the people over the

The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll pooled their talents

Legh Manor: The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll worked together

The Edwin Lutyens-designed tower block that never saw the light of day

Eighty-year-old architectural plans created by the great Sir Edwin Lutyens have reportedly been unearthed in the Lady Flora Pois archives.

An Elizabethan masterpiece in Kent, touched by the genius of Lutyens

The Grange is an early 18th century house which was remodelled by the master himself: Sir Edwin Lutyens.

A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin

Credit: Knight Frank

One of Lutyen's first country houses, a mere two miles away from his family home

In this 150th anniversary year of Lutyens’s birth it’s especially intriguing to find a house on the market undoubtedly designed

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher Published

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon Published