The extravagant seaside splendours of the south coast's most exotic museum

Created for Merton Russell-Cotes’s wife in 1901 and then given to the town, the dazzling interiors of the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum in Bournemouth capture the spirit of the Victorian seaside, says Kathryn Ferry. Photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

In June 1909, Country Life reported on the Lord Mayor of London’s official visit to Bournemouth. It judged the event to be ‘of more than local interest because lovers of Bournemouth and people who owe their restoration to health to its mild climate... are to be found all over the country’. After a ceremony on the pier, dignitaries walked to East Cliff Hall, where Merton and Annie Russell-Cotes gave a tour of the house they had generously presented to the town, together with its contents, the previous year. To mark the occasion, the Lord Mayor received a beautiful souvenir album illustrating what would become the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, ‘a building which occupies a commanding position overlooking the sea’.

More than a century later, this Victorian house museum continues to thrive. The sumptuous interiors of the house, which was created as a birthday present from husband to wife in 1901, are astonishingly well preserved and reflect a rich businessman’s vision of the Aesthetic or ‘Art at Home’ Movement. Displayed here are works of art and sculpture, together with ethnographic objects, amassed over a lifetime of travel. The collection offers an extraordinary window into late-Victorian upper middle-class taste with its enthusiasm for the exotic and respect for the Establishment; the modern British painters represented were approved by the Royal Academy.

East Cliff Hall is also testimony to the phenomenal success of the Victorian seaside. Although Merton Russell Coates (who dropped the ‘a’ and added the hyphen as he rose in status) and Annie, née Clark, did not trade in iron or manufacture cotton (as their respective fathers did), they were nonetheless products of the Industrial Revolution. As inland manufacturing towns grew apace, so did a new generation of coastal resorts, which promised escape from urban clamour and dirt. It’s no coincidence, therefore, that their lives marked time with the evolution of Bournemouth or that their wealth derived from the ownership of the luxurious Royal Bath Hotel, which stands immediately adjacent.

Both were born in 1835, he in Wolverhampton and she in Glasgow, the same year that Sir George William Tapps-Gervis inherited the Meyrick estate and commissioned architect Benjamin Ferrey to reimagine an area of uninhabited heathland at the mouth of the Bourne stream as an exclusive ‘Marine Village’. The Bath Hotel and a row of Italianate villas appeared in 1837. From a mere 165 residents in 1841, Bournemouth’s population rose to 6,000 in 1871; by 1891, it was closer to 60,000.

Russell-Cotes purchased the Bath Hotel on Christmas Day 1876. His biographer, Paul Whittaker, has revealed details that Merton himself preferred to conceal; he worked his way up from being a clerk and commercial traveller in the North-West, with stints in Buenos Aires in Argentina and Dublin in Ireland, to owner of the Royal Hanover Hotel in Glasgow. The ‘royal’ prefix was a marketing ploy he repeated at Bournemouth, referring back to the Prince of Wales’s stay in 1856. To justify it, he immediately employed the town’s surveyor, Christopher Crabbe Creeke (1820–86), to create a suitably regal hotel extension.

A decade later, it was the turn of Creeke’s pupil, Harry Edwin Hawker (1854–1927), to give the Royal Bath a grand new wing with 1,000ft of sea frontage. The interiors, painted by decorative artist John Thomas (1826–1900), were nationally renowned for the luxury of their finish and the works of art Merton had long been collecting. The Royal Bath Hotel became a personal showroom that heavily informed the design for East Cliff Hall.

In 1896, the Russell-Coteses leased a plot of land at the edge of their property and asked Limerick-born architect John Frederick Fogerty (1863–1938) to prepare plans for a ‘chalet’. This choice of name suggests a leisure retreat rather than a mansion; the size of the kitchen and lack of servants’ quarters clarify that it was to rely on the hotel for its domestic services. In Fogerty’s first design, an Italianate belfry-style tower rose above a gabled first floor with decorative half-timbering.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This choice of material may have been Russell-Cotes’s way of proclaiming links to an apocryphal past; illustrated in his 1,000-page memoir is the timber-frame Pitchford Hall, Shropshire (COUNTRY LIFE, November 6, 2019), described as ‘the residence of my kinsman, the late Col Cotes’. He adopted the coat of arms of this gentry family, applying its cockerel crest throughout East Cliff Hall, although, as Whittaker tactfully observes, ‘any connection between the two families is buried deep’. Truth was less important than perception and Fogerty, who came from a line of well-respected Irish architects and engineers, had himself lived in Shropshire before relocating to Bournemouth in 1892.

Local opposition led Fogerty to produce an alternative scheme. Russell-Cotes’s stated vision was for ‘Renaissance with Italian and old Scottish Baronial styles’, but few would consider this an accurate description of the playful sea frontage. French influence has been postulated, but there is also an American flavour that may owe something to the hotelier’s experience of San Francisco. Most obviously, however, it is a compression of Hawker’s Royal Bath Hotel wing, the central and side bows are concertinaed together and the whole reduced from three to two storeys.

At East Cliff Hall, the bows maximise the sea views (internally, the upstairs bedroom windows drop almost to the floor to create walls of glass) and rise to tiled, mansard roofs trimmed with decorative cast-iron balustrades (Fig 1). Striped copper canopies that shelter the ground-floor verandah and upstairs bedrooms lend the façade its distinctive seaside frills. The canopies are a borrowing from Regency coastal villas. By contrast, the street front is markedly plain. Because the house was built into the cliff, only one floor rises above road level and, although there is a classical entrance, the wall next to it is blank.

Visitors now arrive through a 1990 extension off the cliff path, but the original entrance vestibule established the decorative tone with Annie Russell-Cotes’s mosaic monogram on the floor, heraldic stained glass, stencilled walls and tiled dados. On the grand staircase (Fig 2), different levels reveal themselves all at once to symphonic effect. A gilded plaster reproduction of the Parthenon Frieze draws the eye up towards a dome of stained glass representing the deep blue of a night sky studded with stars, owls and bats. Around its rim are the accent lines of bright scarlet repeated throughout the interior.

Beyond, the double-return stair leads up to a balcony, crammed with the gilded frames of paintings interspersed with niches designed for marble statuary and down to the main hall at the heart of the house (Fig 5). Herein lies the cleverness of Fogerty’s plan. The unconventional layout was determined by the desire for a grand gallery space, but the fact that this could be situated in the centre and top-lit allowed all the rooms leading off it to benefit from glorious sea views. A bow-fronted conservatory, with curved roof and an unusual tier of ruby glazing, took in an even more expansive prospect and the decorative potential of all this glass was fully embraced. A stained-glass depiction of the sun’s daily cycle across the sky filters light into the main hall, installed as a replica after a bombing raid of 1941, and Japanese-style bird paintings by John Thomas appear in the bedroom windows.

Thomas enjoyed a considerable reputation during his lifetime, but only the Russell-Cotes Museum survives to attest to his skill. Born in Birmingham and trained in the japanning works of Wolverhampton, Thomas painted ships in Glasgow before moving to Manchester, where he worked on churches and chapels, as well as the Royal Exchange and the Reform Club. His books of Japanese Sketches and Bird and Flower Studies showcased his favourite subjects; in August 1889, The Journal of Decorative Art proclaimed ‘his facility of reproduction is remarkable’.

That year, Thomas was completing a second cycle of work at the Royal Bath Hotel, where both public and private rooms were enlivened by his murals. Many featured exotic birds, which Russell-Cotes requested again for East Cliff Hall. Peacocks preen their way around the frieze in the dining room and, in the study, golden Japanese sun motifs light orange clouds as birds fly to roost among the painted trees on the ceiling. Japanese influences are a recurrent theme and had been since client and artist introduced the newly fashionable trend to Bournemouth in the late 1870s. The Royal Bath’s Japanese Drawing Room became an attraction in its own right, especially after it was crammed with the contents of more than 100 packing cases of souvenirs bought during the Russell-Coteses’ seven-week stay in Japan in 1885, part of an 18-month world tour. After Annie’s death in 1920, these treasures were rehoused in the newly designated Mikado’s Room at East Cliff Hall.

Further Japanese references include the imperial emblem of a stylised chrysanthemum bloom, which appears across the front of the verandah. It also features in the staircase newel caps, the posts of the hall balcony railings and with the Cotes family cockerel in a frankly bizarre design for the morning-room chimneypiece. All of East Cliff Hall’s fireplaces were bespoke creations by Bourne-mouth cabinetmaker William Mabey (1848–1931), crafted to fulfil the late-Victorian ‘one-style-per-room’ aesthetic. The delicate wooden inlays and mirrored overmantel of the drawing-room fireplace reference the Italian doors and rosewood display cabinet once owned by Empress Eugénie of France, which inspired that room’s decorative scheme.

In the darker, more masculine, dining room, the sturdy oak fire surround is enclosed in an inglenook with panelled corner seats (Fig 3). The internal lobby space of the Moorish Alcove (Fig 7) has trompe l’oeil walls, decorated after the Russell-Coteses visited the Spanish Alhambra in 1910, that add another exotic element to the enfilade of themed rooms. Wooden fretwork screens made by Mabey for the dining room, drawing room, study and boudoir (Fig 4) present rare evidence for the turn-of-the-century interior fad for nooks and cosy corners. These were used to subtly divide the space, often accentuating the bowed shape of the rooms and framing the sea views.

East Cliff Hall’s history as a municipal art gallery began in 1908, but the gift provided for the Russell-Coteses to live out their days there. In 1916, Harry Edwin Hawker was brought in to build a gallery extension in a refined classical manner suited to its use (Fig 6). Regular opening hours commenced a year after Russell-Cotes’s death in 1921 and, in 1926, the gallery was again extended by Hawker, at the expense of the Russell-Coteses’ heirs.

The house represents the tastes and foibles of a couple navigating their ascent up the social hierarchy. Russell-Cotes’s voice perhaps speaks loudest, but, given the affection that sustained a 60-year marriage, it seems likely that decisions were made in partnership. The Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum is nationally significant, but it is also a product of Bournemouth, paid for by the town’s increasing prominence as a seaside resort, made by architects and artisans who made their home there, shot through with the artistic aspirations of its well-travelled owners.

Acknowledgements: Sarah Newman and Duncan Walker. Visit www.russellcotes.com

Oh, we do like to be beside the seaside: How coastal house prices have bucked the trend to keep on rising in 2024

The Country Life guide to Dorset: Where to go, what to see, where to stay and where to eat

Magnificent coastline, beautiful countryside, irresistible romantic ruins and wonderful local produce make Dorset a superb place to go. Here's our

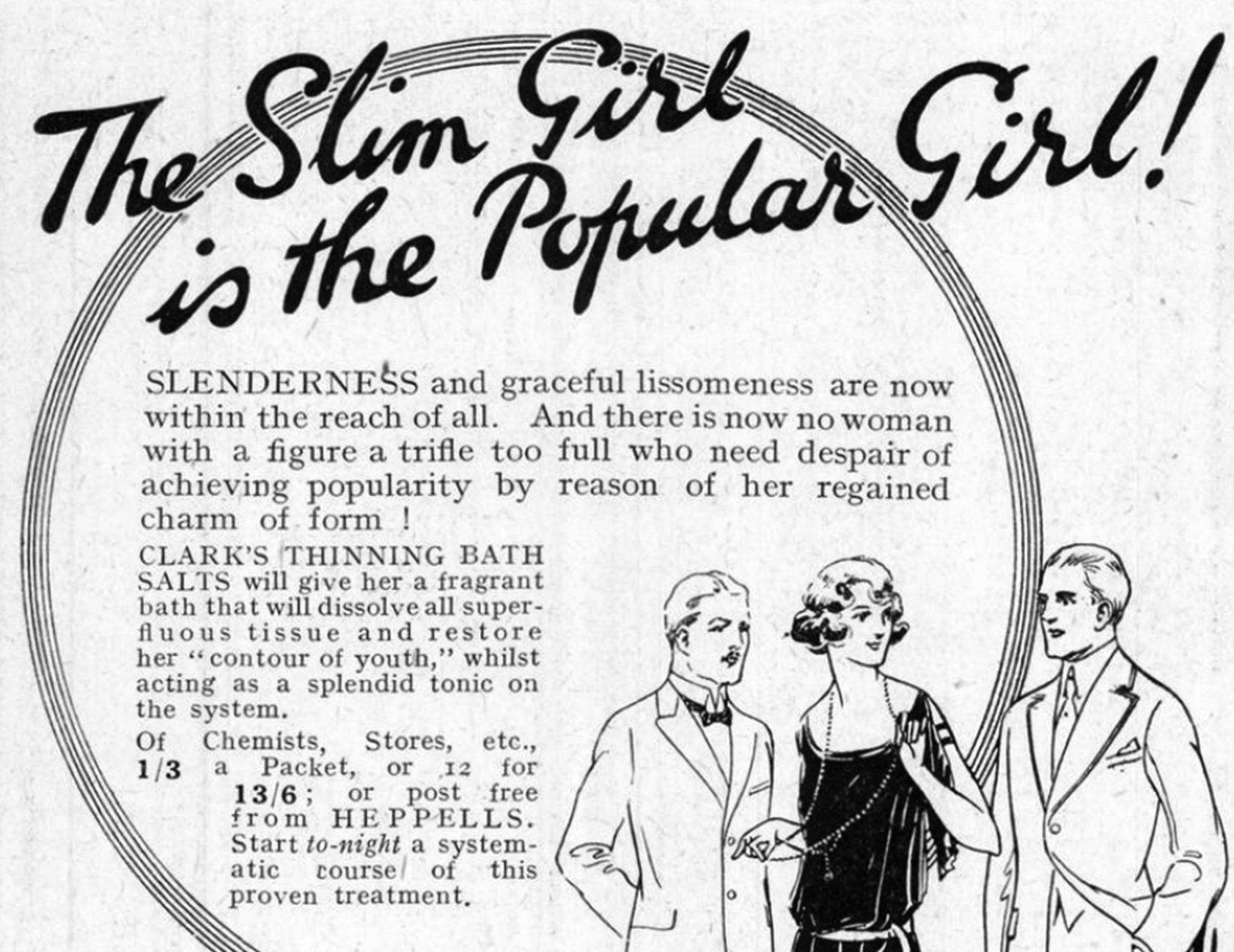

Country Life's best, worst and funniest adverts of 1923, from Burberry and thinning baths to the SUV of a century ago

From telephone-equipped hotel rooms to cars ‘for lady drivers’, the advertisements featured in Country Life in 1923 captured Britain’s evolution

The best regional art galleries in Britain, from Cornwall to Orkney

Wherever you are in Britain, you’re never far from an interesting gallery. Here we present an eclectic round-up of 45