Inside the Shropshire house where the Royal Family planned to shelter if Britain was invaded during the Second World War

A house prepared as a safe retreat for the Royal Family in the Second World War has recently returned to family ownership and is thriving once again. Marcus Binney reports.

Pitchford Hall is a 16th-century house that vies with Speke Hall, Liverpool, and Little Moreton, Cheshire, as the most beautiful timber-framed house in England. When the young Queen Victoria visited aged 13 in 1832, she caught its character perfectly, describing it as: ‘A curious looking but very comfortable house. It is striped black and white, and in the shape of a cottage.’

The approach to Pitchford is along narrow by-roads, with a distant view of the Welsh hills, so it is easy to understand why, in 1940, it was one of three country houses chosen as safe retreats for the Royal Family in the event of a German invasion during the Second World War. The others were Madresfield Court, Worcestershire, and Newby Hall, Yorkshire.

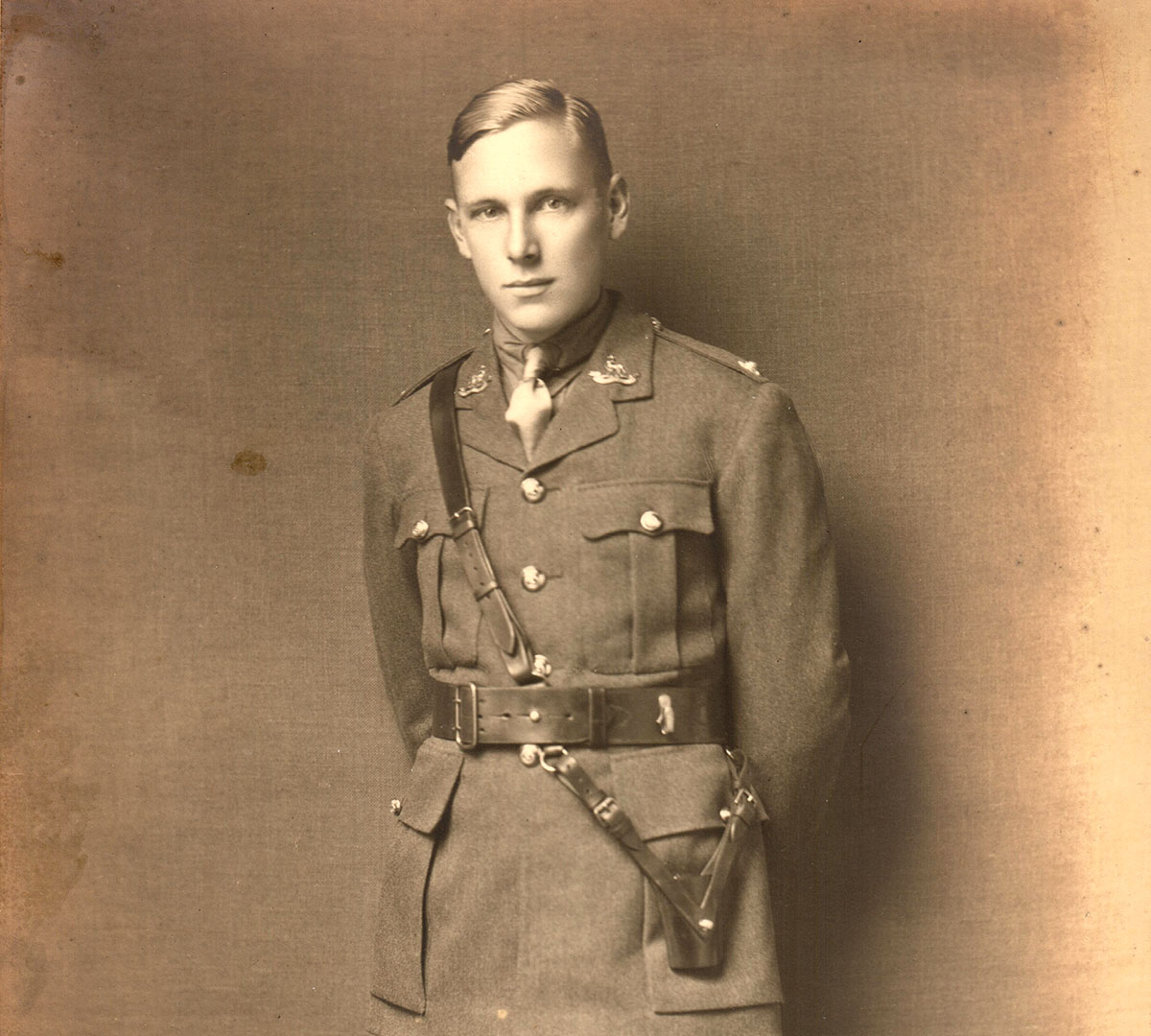

A special company of the Coldstream Guards, based at Bushy Park next to Hampton Court and named the Coats Mission after its commander Sir James Coats, was set up to transport the Royal Family to these retreats.

Defences at each property consisted of a series of slit trenches around the house, carefully concealed so no one would be alerted to the plans. Dispatch riders were trained to precede the royal convoy, stopping ahead at every crossroads to halt traffic.

If the enemy reached the Midlands, the plan was to rush the Royal Family to Holyhead for transport to Canada by the Royal Navy. A pantechnicon had been fitted out as a travelling living room and Gothic Revival Hatley Castle, built in 1908 on Vancouver Island, had been bought as the residence in waiting.

‘He galloped me through the house, pointing out the contents which he thought he would give with it…'

It would be interesting to know if the King and Queen had a voice in choosing the houses. As Duke and Duchess of York, they had visited Pitchford in 1935. For Pitchford, it meant a lucky escape from requisitioning and, when James Lees-Milne arrived on March 17, 1944, investigating houses for the National Trust, he found it looking highly romantic amid spring-flowering crocuses and primroses.

The architect W. A. Forsyth conducted him upstairs to a small, shapeless room in the west wing, where the owner Sir Charles Grant was sprawled listening to the European news. ‘He galloped me through the house, pointing out the contents which he thought he would give with it… His proposals are vague, and he does not intend to transfer any land over and above what the house stands on.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On the lawn, Forsyth met Lady Sybil, daughter of the Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, who took him to the Orangery where she lived: ‘Her sanctum converted by her into one large living room with a fire and one bedroom.’

The gift to the Trust never took place and, two years later, Sir Charles’s son Robin married, acquiring a dashing and adventurous stepdaughter, Caroline Combe, to whom Pitchford later passed. Caroline, who had earned notoriety by releasing white mice at Queen Charlotte’s Ball, was a reed-thin model and beauty, and later a fashion journalist and boutique owner in swinging London. After turning down Mickey Grylls (and, reputedly, resisting advances from Marlon Brando) she married, in 1968, Oliver Colthurst, the younger son of Sir Richard Colthurst, 8th Baronet of Blarney Castle, Co Cork.

By the 1980s, Pitchford was in urgent need of extensive repair. Happily, the best man for the job was nearby, Shropshire architect Andrew Arrol, who directed an exemplary programme of repair over 12 years. This was generously supported by the Historic Buildings Council, energetically chaired at the time by Jennifer Jenkins (wife of Roy, then our man in Brussels). Arrol recalls her visit: ‘I told Oliver don’t talk too much and don’t look too prosperous.’ Instead Oliver, in best Errol Flynn style, appeared in a smoking jacket with a large cigar and a glass of brandy.

The house revived to mesmerising beauty, Pitchford had only just begun to open to the public when, in 1992, tragedy struck. The Colthursts were caught in the Lloyds insurance meltdown. The Trust drew up a rescue plan, but the £7 million endowment sought was beyond the National Heritage Memorial Fund’s (NHMF) resources.

Intrepidly, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, newly appointed chairman of English Heritage, offered to step in and ‘garage’ the house, as he put it, while he arranged a rescue plan. The Colthursts offered to gift the house to the nation, if £1.8 million could be paid for the contents, which the NHMF was prepared to do. But Sir Jocelyn needed Government approval and this was refused.

I was there when the news came through, not from the Minister, but from the BBC. The Champagne was on ice and the omens looked fair. Instead, it turned into a wake.

A contents sale was held on the lawn on September 28–29 and, in November, the house sold to an unnamed buyer, who later transpired to be a Kuwaiti princess. Although the prospects initially appeared good, the hall was left neglected as the stable range served briefly as a stud. The pill was doubly bitter for the Colthursts, for they not only had to sell the house to pay the Lloyds debt, but also had to repay every penny of the £350,000 historic-buildings grants.

Nonetheless, the saga took a sudden, happier turn when the Colthursts’ daughter, Rowena, and her husband, James Nason, a political lobbyist, bought back the house in 2016. Pitchford is on the mend – visits can be booked through www.historichouses.org and the General’s Quarters in the west wing is a comfortable holiday let, sleeping 14. The Orangery, where Lady Sybil Grant lived, has recently been restored for events and still retains her 1930s interiors.

The recorded history of Pitchford goes back to Edward the Confesssor and, from about 1086, the manor was held by Sir Ralph de Pytchford. The name presumably refers to the natural well of pitch, which still survives, close to the house. Another Ralph inherited in 1211 and built the church above the hall. The astonishing wooden effigy of his son, Sir John de Pitchford, is one of a series of remarkable tombs surviving there.

The traces of an early hall house, probably 13th-century, are recorded by Arrol, subsumed within the west wing of the present building; the main evidence is timbers blackened by open fires visible in the roof space of the west wing, marking a pair of Queen posts.

The estate sold in 1301 to Walter de Lang-ton and passed through various hands before being bought in 1473 by Thomas Ottley. He made his fortune from finishing Welsh cloth and he also had a house in Calais. It was his descendant in the mid 16th century, the prosperous Shropshire clothier Adam Ottley, who remodelled Pitchford in its present form, extending the medieval house and creating the three-sided entrance courtyard with gables.

'It’s all the more important as the first extant example in a group of such houses – sometimes collectively described as the Shrewsbury School – built by prosperous Shrewsbury clothiers intent on becoming knights and squires'

Early views and photographs, including those published in Country Life in 1901, show the courtyard enclosed on the fourth side by an arched gateway and wall, probably dating to this period.

Ottley turned to Master John Sandford for the work, a member of an important dynasty of Shrewsbury carpenters. The earliest mentioned was Humphrey Sandford, who was sworn Freeman of the Shrewsbury Guild of Carpenters and Tylers in 1540. John, probably his elder brother, was warden of the carpenters guild and, when he died in 1566, probably before the hall was finished, he was still in possession of a farm leased to him by Ottley in 1549, as part of the consideration for building the ‘mansion place’. His sons, Ralph, Thomas and Randall are also recorded as carpenters.

The house bears all the hallmarks of Sandford family work. Among these are bold diagonal strutting, pilasters terminated by grotesque heads and carved gables with trailing vines. Previously, pomp and wealth were manifest in close studding – massed ranks of upright timbers, as seen in the surviving medieval range – but here, a new language of bold patterning emerged, part geometric, part abstract, a constant play of quatrefoils, herringbones and lozenges.

It’s all the more important as the first extant example in a group of such houses – sometimes collectively described as the Shrewsbury School – built by prosperous Shrewsbury clothiers intent on becoming knights and squires. The earliest dated house of this type in the town itself was the now demolished Lloyds mansion in the square, built by David Lloyd in 1570. Another is Ireland’s Mansion in the High Street and the front elevation of the Drapers Hall of 1576–82.

It must have been Ottley’s son who commissioned a pair of remarkable incised alabaster tombs in the church for his parents, himself and his wife. The former is inscribed as having been ‘drawn and graven by John Tarbrook [of Be]udly carver Anno 1587’. Sir Francis Ottley (1600–49) was a strong Royalist and Governor of Shrews-bury who helped initially secure the county for the King and negotiated the surrender of Bridgnorth, but the Parliamentarians prevailed and he fought a desperate campaign to free his estates from sequestration.

His eldest son, Richard Ottley (1626–70), a captain in the Royalist army, was knighted on June 21, 1660. A gentleman of the privy chamber to Charles II, he sat as MP for Shropshire from 1661 until his death on August 10, 1670.

Pitchford retains from about this period a tree house set in a spreading small-leaved lime. It first appears on a map dated 1692 and is timber-framed to match the house.Internal plasterwork is mid 18th century and was probably by Thomas Farnolls Pritchard, creator of the famous Ironbridge at Coalbrookdale. He had an extensive country-house practice and was presumably also responsible for the slim, lean-to additions to the main house supported on clustered columns.

These created a cloister-like arrangement of service access to the main rooms. He may also have inserted sash windows in parts of the main building, which are illustrated in some early photographs.

From 1883–89, the house was romanticised in a glorious and subtle way by George Devey to create a seamless, harmonious whole. Devey transformed a plain and over-sized late-Georgian wing (also shown in early photographs) into an attractive kitchen courtyard that blended perfectly with the 16th-century house. Ingeniously, he retained part of the colonnades and, inside, an impressive stone cantilevered staircase rising to the second floor survives.

Devey also created a new entrance on the north side, opening into the great hall, ennobling the skyline by increasing the number of star-form chimneystacks and allowing the owners to create a garden in the south court opening onto the park and river below. He also replaced the sashes with Elizabethan-style leaded panes.

Inside, Devey enlarged the great hall by extending it into the dining room, after which he moved the old hall panelling into a new drawing room. One key painting to survive in the house by virtue of being a listed fitting is a 1611 portrait by a follower of Hieronymus Custo-dis (d. 1593) of Lady Cassandra Ridgeway, whose daughter married Richard Ottley.

The new owners have now embarked on the challenging task of bringing back, or replacing lost contents, intent on making Pitchford Hall a family home once again which can fascinate visitors as its complex history is unravelled year by year.

To find out more about Pitchford Hall, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, visit www.pitchfordestate.com.

The incredible tale of my father's escape from 'Italy's Colditz'

Today, we might think of spending a few months in a world heritage site in Southern Italy as an enormous

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin Published

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson Published