How libraries merged with living rooms to become the ultimate in Regency country house chic

By the early 19th century, the library-living room had become an essential element of the country house. John Martin Robinson looks at the development of this space and the wild enthusiasm for books that encouraged it.

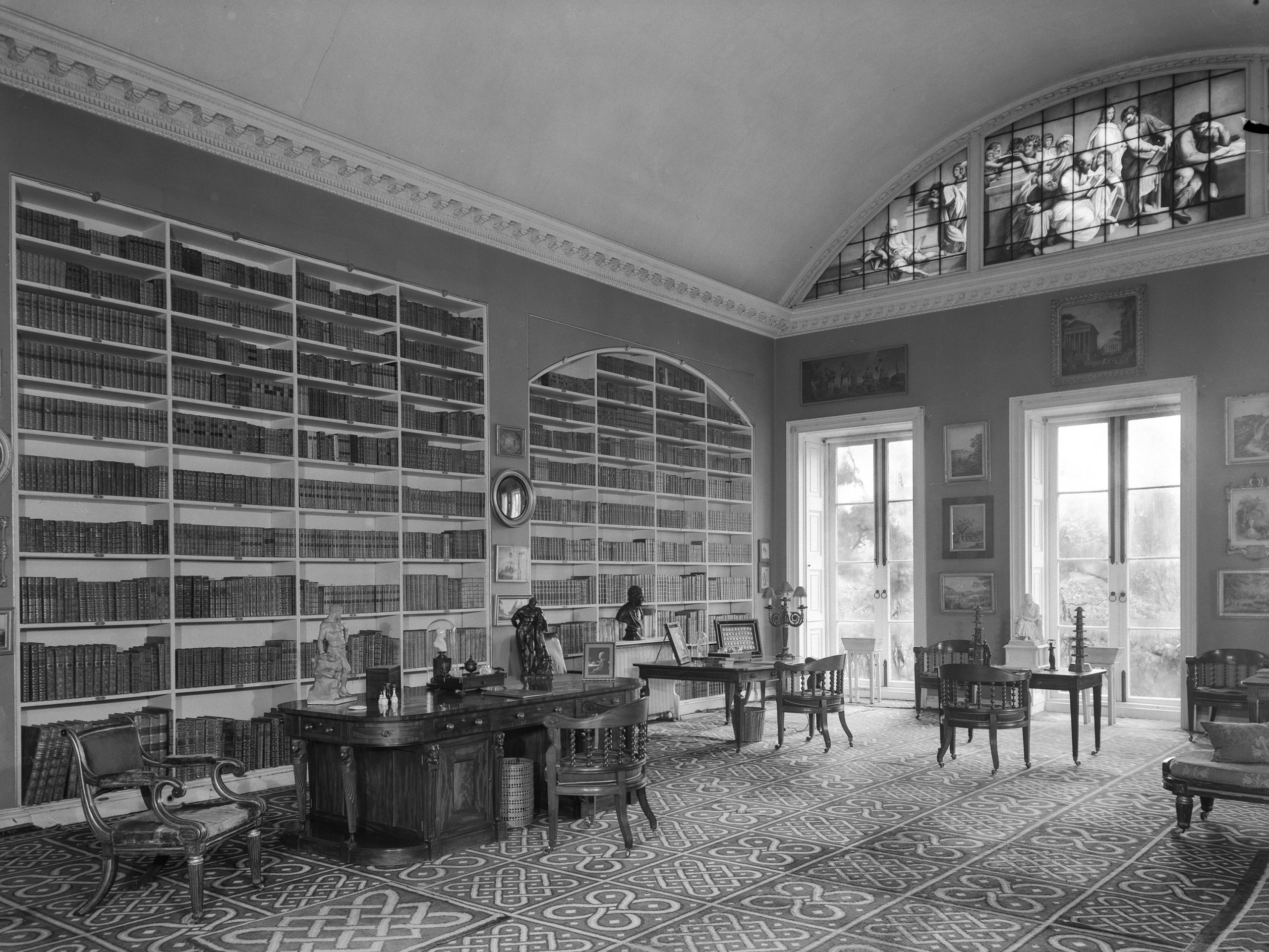

The library was — together with the drawing room and dining room — one of the three principal living interiors in the English Regency country house. It was an informal room, comfortably furnished and suited for the entertainment of a house party. For its owner, it provided occupation for a wet-weather day, not only reading or writing, but rearranging and cataloguing books, browsing and looking at prints, drawings, medals and coins.

In many of these particulars, the library as a living room was an important innovation. As Mark Purcell demonstrates in his ground-breaking history The Country House Library (2017), during the 17th and early 18th centuries, collections of books were often kept in small, private spaces, set apart as at Ham or Dunham Massey. At Arundel or Norfolk House in the first quarter of the 18th century, the libraries adjoined the secluded apartment of the private chaplain of the Duke of Norfolk, not the drawing rooms.

From the 1730s, however, book rooms became steadily more prominent, with examples such as William Kent’s library, planned as the centrepiece of the family wing at Holkham, or Lord Harley’s large library on the piano nobile at Wimpole; both those houses, of course, belonged to serious book collectors. During the later 18th century, in the houses of Adam and Wyatt, libraries became rooms of real architectural pretension. At Syon and Heveningham, they opened straight off the drawing rooms as principal sitting and entertaining spaces and, at Althorp and Woburn, Henry Holland made the libraries the biggest and finest sitting rooms in the house.

In this period, libraries also came to be distinctively furnished for comfort and for educated pastimes. They contained writing tables, sofa tables, reading tables, folio cabinets, bookstands, games tables and circular central tables on which to display folio books and albums of prints and engravings. They also sported a varied range of upholstered seat furniture — sofas, couches, armchairs, library chairs, ottomans — which were often arranged informally in freestanding groups in the middle of the room or around the fireplace, rather than placed formally along the walls, as had been the practice earlier.

The freestanding Grecian couch was a Regency invention and a very popular one to judge from contemporary descriptions of house parties, where at least one of the guests was always to be found lolling on one after dinner.

Foreign visitors to England were intrigued by the sybaritic seat furniture in English houses, especially in libraries, and of London clubs, such as The Athenaeum. Prince Pückler-Muskau in the 1820s thought the art of comfortable seating had been developed in early-19th-century England to a higher degree than in any other place or any other age. He was especially taken by the moveable armrests on library chairs, designed to support books, and the scatter of footstools that allowed a reader to recline and stretch out in a deep, cosy chair and nod off over a volume.

A properly furnished library-living room formed part of the plans for George IV’s successive residences at Carlton House, Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace. The Prince Regent’s room arrangements mirrored the Enlightenment tastes of the educated Whig aristocracy. At Arundel, Chatsworth, Belsay, Oakley, Tatton, Sheringham and other Regency ensembles, the library was one of the largest and principal sitting rooms.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Libraries were also contrived in or added to older houses in this period, as at Broughton Hall, Barnsley Park and Deene. There was a fine example at Stourhead, for Sir Richard Colt Hoare, a distinguished scholar and the historian of Wiltshire, but many owners were book enthusiasts, easily conversant with the classics, philosophy and history and enthusiastic about newer Enlightenment studies in natural history and travel.

All these subjects tended to be well represented on the shelves of late-Georgian landowners, alongside the inevitable collections of Bibles and religious works. More idiosyncratic and personal concerns were displayed, too, such as those of Sir Thomas Swinburne (the poet’s grandfather) of Capheaton, Northumberland, whose encounter with the Marquis de Sade on his Grand Tour was reflected in the books on his shelves.

This emphasis on the library in the Regency country house also reflected the bibliomania of the period, when wealthy book collectors vied with each other to buy rare editions, fine bindings and beautiful manuscripts. The 3rd Duke of Roxburghe, a bachelor, acquired three houses in St James’s Square, all piled high with tomes. These were sold after his death in 1804 in a celebrated sale over several weeks in May, June and July 1812, reaching record prices. The sale’s high point was the purchase by the Marquess of Blandford, son of the 4th Duke of Marlborough, of a first edition of Boccaccio’s Decameron, printed by Christophorus Valdarfer of Venice (1471) for £2,260, then the highest price ever paid for a book.

At the instigation of the Revd Thomas Dibdin, author of Bibliomania; or Book-Madness (1809) and librarian to the 2nd Earl Spencer, a group of 18 collectors dined together that evening and founded the Roxburghe Club, with Spencer as the chairman. It survives today as the oldest and most distinguished society of book collectors in the world and still holds a memorial dinner every June, at which a toast is drunk to the ‘immortal memory of John Duke of Roxburghe... and the Cause of Bibliomania all over the world’.

Unfortunately, the enthusiasm of Lord Blandford exceeded his pocket and his choice library at Whiteknights Park, near Reading, was sold off to pay his debts in 1819. The 2nd Earl Spencer acquired his Boccaccio ‘for half the price’ of 1812. Lord Blandford did, however, secure his favourite treasure, the astonishing 15th-century Bedford Hours, from the bailiffs. Lord Spencer’s superb library was sold in turn in the late 19th century to Mrs Rylands of Lancashire and now forms part of her great library in Manchester. Nevertheless, the Althorp library remains one of the most beautiful rooms in the house, replete with its Grecian mahogany couches and leather-upholstered library chairs.

Lord Spencer was a great influence on his nephew the 6th Duke of Devonshire, another notable bibliophile (or bibliomane). Having inherited the libraries of his mother, the beautiful Georgiana, and his cousin, the scientist Henry Cavendish, the 6th Duke added to them extravagantly, buying extensively at the Roxburghe Sale and acquiring whole libraries elsewhere, including that of Bishop Dampier of Ely, and John Kemble’s collection of plays. The Chatsworth library, together with the 6th Duke’s sculpture gallery and the garden, was his pride and joy.

Soon after his father’s death, the Duke converted the Long Gallery at Chatsworth into a library: ‘In 1815 I began to pull out the panels, and convert them into book shelves’, keeping the ceiling with plasterwork by Edward Gouge and painted roundels by Antonio Verrio. It looked handsome, but did not provide enough space for books, so there was a further transformation in 1820, as part of Jeffry Wyatville’s vast expansion and remodelling of the house. Two tiers of mahogany bookcases by Armstrong & Seddon with a gallery guarded by a gilt rail were inserted.

The Duke’s love of books radiates out of the pages of his enchanting Handbook of Chatsworth (1844) and speaks of the enthusiasms shared by many late-Georgian Englishmen: ‘The collection here is exceedingly rich in early editions, in large paper copies of the classics, in books of science and voyages and travels. It is classed in accordance with Lord Spencer’s system.’

He spent happy days there when the Derbyshire weather was too cold or wet for outdoors, engaged in what he called ‘booking’. As Cavendish the scientist did, he made his books available to scholars. He wrote: ‘The pleasure has been great (besides that of possessing so many treasures) of finding that a pursuit which may have had a good deal of bibliomania in its composition, has been of real use to several men of letters.’

The Duke of Devonshire spoke for many of his contemporaries who embellished their houses with magnificent late-Georgian libraries. The 11th Duke of Norfolk, another Whig, converted the former Elizabethan Long Gallery at Arundel Castle into a library of his own Gothic design, fitted out in carved mahogany. It is 112ft long with galleries, as at Chatsworth, and contains about 10,000 books.

In Norfolk’s case, he inherited the large 18th-century library of Edward the 9th Duke, formed between 1762 and 1772, but added to it many treasures, such as beautifully illustrated natural-history books, illuminated manuscripts and 16th- and 17th- century printed books, including a First Folio of Shakespeare, all still in situ.

He, too, patronised scholars. The Arundel red-velvet furnishings — with the usual array of sofas, couches and armchairs — were commissioned from Morant for Queen Victoria’s visit in 1846, when the room was used after dinner.

The Chatsworth library was Classical and the Arundel library Gothic, styles that reflected two deep-rooted aspects of English intellectual life. The Georgian love of Greece and Rome, expressed in the literature of Antiquity, underpinned public- and grammar-school education and Whig political, as well as aesthetic, culture.

Gothic spoke of antiquarian enthusiasm, as expressed, for example, in Horace Walpole’s library at Strawberry Hill, inspired by tombs at Westminster Abbey. Even the supreme Regency advocate of neo-Classicism, the architect Sir John Soane, worked in Gothic to accommodate the Marquess of Buckingham’s collection of ‘Saxon’ manuscripts (medieval charters) in the so-called Saxon Library at Stowe.

The stylistic choice was even-handed, however, and Hoare, the enthusiastic expert on the prehistoric and medieval antiquities of Wiltshire, came down on the side of Roman when it came to the large new library he added to Stourhead to his own ideas by Moulton & Atkinson in 1792, which was beautifully furnished by Chippendale the Younger.

Even the carpet was woven, in green and yellow, to represent a Roman mosaic. The book collection was a research library for Hoare’s own historical work, being full of topographical books and records. It was sold in 1885, but replaced with books inherited from Wavendon, another family house.

The Greek Revival was also popular for 19th-century libraries, redolent of Homer and Pythagoras, as at Belsay and Oakley. Christopher Hussey wrote perceptively in Country Life of C. R. Cockerell’s library at Oakley Park, Shropshire: ‘The Hellenic style was particularly well suited to libraries because bookcases could be effectively integrated with its rectangular forms. In this pleasing instance, the centre of each wall is regarded as solid, containing the fireplace, a double door, a wide window... and the bookcases as the “curtains” between them, flush on the long walls.’

The books themselves were often the determinant in building a library. Many late-Georgian incarnations were created to be beautiful and special settings for collections of books that meant a great deal to their owners. This can be seen at the Bow Room at Deene Park, designed by an unknown architect—made to house the historically fascinating Elizabethan library of the recusant Sir Thomas Tresham, who built the Triangular Lodge at Rushton, inherited 200 years earlier via the marriage of Tresham’s daughter to a Brudenell of Deene — or the glorious library of Henry Holland at Woburn Abbey, containing the 5th and 6th Dukes of Bedford’s lavish natural-history books.

As well as being beautiful architecture, the many surviving libraries in British country houses provide one of the most intimate insights into the educated interests and informed culture of our forebears. As the 6th Duke of Devonshire’s Raphaelesque decoration by John Crace in the Lower Library at Chatsworth (quoting from Davenant) pronounces on a painted scroll: ‘Books, the assembled minds of all that men held wise.’

The restoration of Sheringham House, Humphry Repton's 'darling child' and 'most favourite' work

Jeremy Musson looks at the restoration of Sheringham Hall in Norfolk, the home of Paul Doyle and Gergely Battha-Pajor, looking

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon