A rare look inside Higham Hall, home of the Prince of Wales’ favourite architect Quinlan Terry

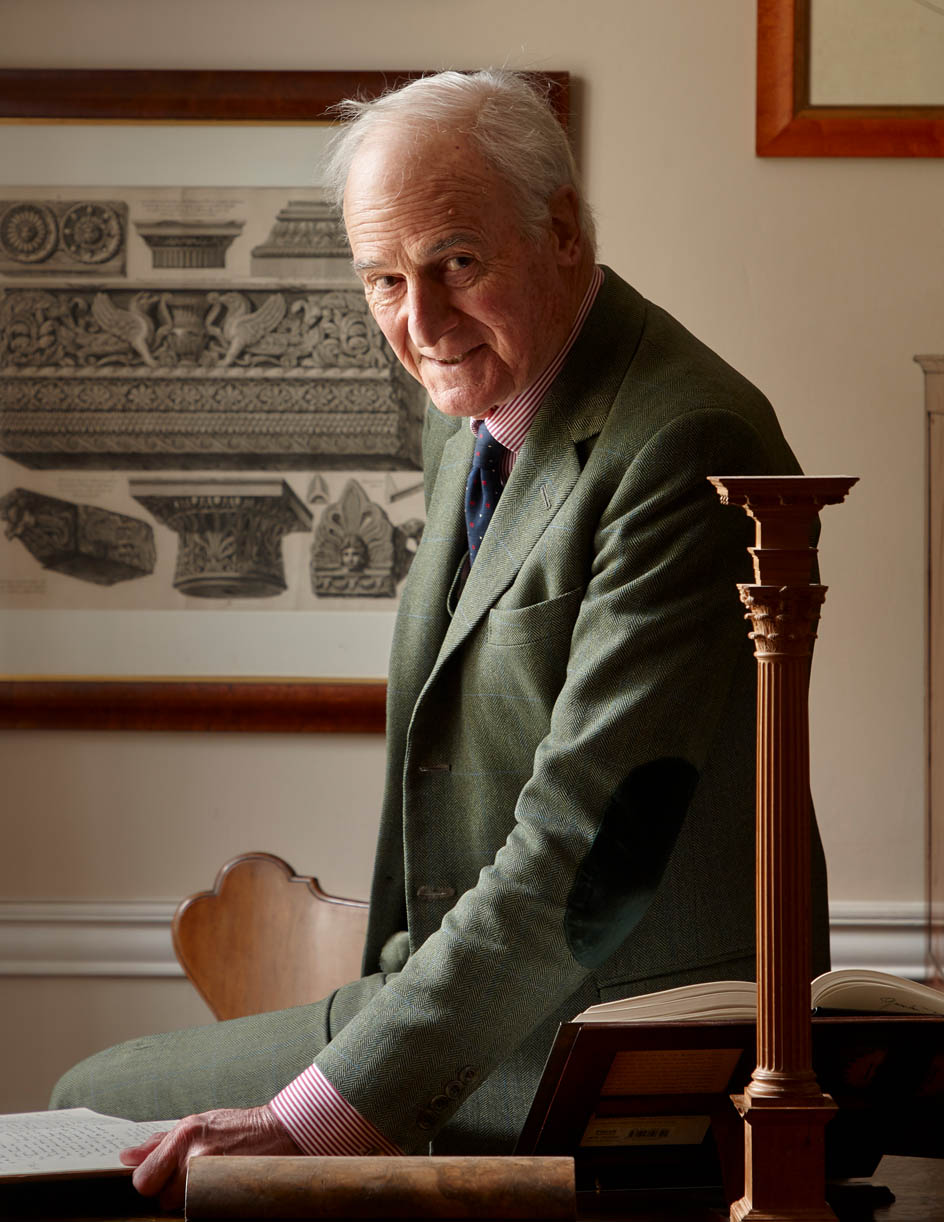

Higham Hall in Suffolk is the home of Quinlan Terry, the favourite architect of HRH The Prince of Wales and a leading contemporary exponent of Classicism. Clive Aslet reports; photographs by Paul Highnam.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Modern architects often live in Georgian houses. Strangely, today’s Classical architects seem not to return the compliment and the home that Quinlan Terry and his wife, Christine, have occupied since 1980 is everything you would expect of Britain’s most famous Classicist.

Sheltered by a tall wellingtonia, a gravel sweep leads to an entrance façade of ‘white’ brick. In this case a yellowish grey, it is one of the austere Suffolk whites that were so favoured during the Regency, with its aesthetic horror of red brick in landscape settings. Five sets of windows are set into relieving arches, two storeys tall; above the deep, Italianate eaves is a pediment. In the centre of the composition is a Doric porch.

We know the date of this building from a brick carved with 1811 and the initials JS — for the owner James Stutter — with those of his family.

Who was the architect? It is a point discussed by Charles Lynne in his analysis of the history of the house (Country Life, June 2, 2007). Sir John Soane was often in East Anglia, designing country houses and repairing churches, at the start of his career in the 1780s, but, by 1811, he had moved onto bigger things.

The best country house architects in Britain

Country Life has once again delved into its to update the list of the finest architects in Britain — an

It certainly seems, however, that the local Wheeler dynasty of builders constructed it; the name Wheeler and the date 1810 were found in pencil on the box of a window sash during restoration work.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, little about this house is as it seems. From its position next to the church, one might have imagined it to have been a rectory, although it seems always to have been known as Higham Hall and James Stutter is always known as ‘Esq.’ in the few appearances he makes in Suffolk records (for example, as a member of the grand jury at the Bury St Edmunds assizes).

Furthermore, the elegant façade is only one bay deep; it was attached to an earlier house built of 2in red bricks, dating from the 17th century or earlier. Into this older house, Stutter cut a large window bay for the drawing room, as can be seen from the brickwork; he also increased its height.

For Mr Terry, the attraction of Higham — a hamlet more than a village, although principally composed of large houses — was its location. Raymond Erith established his practice in a warren of Tudor rooms on Dedham High Street, previously used as the town’s telephone exchange. Continued as Erith & Terry, it has remained there ever since.

Little has changed, although, eventually, the pages of The Times that, with an eye to economy, Erith had used to paper his office in 1957 were replaced with an ingenious wallpaper of a similar vintage, designed by Mr Terry in 1964. It consists of a single square that forms a coffered pattern, like a Roman ceiling, when four squares are rotated and joined together (beware, would-be imitators, it’s very difficult to hang).

Higham Hall is only eight minutes away by car, so is ideally placed for Mr Terry, who, in his early eighties, has no intention of retiring from the practice, but likes to follow his long-held routine by eating his luncheon at home.

Before 1980, the Terrys’ home had been a Tudor hall house converted into four farmworkers’ cottages, with the significant name of Winterfloods. With a growing family — they had four children at that time — they needed more space and found it in Higham Hall. It was a move up.

At that time, the prospects for Classicism were not what they have since become. Private patrons had kept the flame burning throughout the chaotic, high-tax 1970s, but the opportunities to build were limited. After Erith’s death in 1973, Mr Terry lavished his knowledge of Classical ornament on garden buildings and other small, often ingenious works, but the stream of great country house commissions had yet to come.

As a result, on arriving at Higham, the Terrys made few structural alterations to the house beyond removing the render that covered the garden front (which was, in any case, falling off). Instead, periods of professional dearth gave Mr Terry the necessary time to plan and execute a series of decorative schemes that are what now give the house its particular charm.

The garden goes down to Constable’s River Stour, which is the boundary between Essex and Suffolk, and is joined by its tributary, the Brett. To one side, a tennis court is set at an angle. The need to conceal this, by planting a beech hedge, suggested that another could be positioned on the other side of the lawn, to create a false perspective, tricking the eye into thinking that the garden is longer than it really is and centred on Langham Hall a mile away to the south.

Mr Terry had discovered the joys of false perspective when staying at the British School at Rome and Jeremy Blake, a future member of the Erith & Terry office, was encouraged to write a book on it, La Falsa Prospettiva (1982).

In England, Mr Terry began a flirtation with the Baroque through commissions such as the follies he built for the late Alistair McAlpine at West Green House, Hampshire (a cause of some head-scratching to its current owner, the National Trust).

At Higham, what had been a plain lawn was laid out as a parterre, with geometrical compartments in box. In the centre is an avenue of yew shapes marching down to the water, diminishing in size as their lines converge. Although the scheme met with scepticism from some of the Terrys’ friends when it was first planted, time has proved it to be a triumphant success. The yews nearest the water have survived the floods that come in winter (they are planted on slight mounds to raise them above the water level).

Not so long ago, the scheme was improved by a hedge to divide the space; to ensure it could catch up, it was planted in fast-growing garden-centre leylandii. Clipped like yew, this much-disparaged tree proves its worth.

Beside the river is a shelter for an old Oxford punt, much used for picnics. In family parlance, the Brett can be known as the Brenta, evoking dreams of Palladio in misty Suffolk.

Two things strike the visitor on entering Higham Hall: the faux masonry of the walls and the preponderance of linocuts that hang on them. To readers who know Mr Terry’s practice for its sumptuous country houses, such as Ferne Park, Dorset (Country Life, May 5 and 12, 2010), and Kilboy, Co Tipperary (Country Life, September 7, 2016), the severe and hand-wrought character of the interior may come as a surprise, because the decoration manifests an earlier phase of Mr Terry’s development and his roots in the Arts-and-Crafts movement.

Both the faux masonry and the linocuts are, in whole or in part, works of Mr Terry’s own hand. He set out the joints of the first part of the masonry using a T-square; the effect of mortar is achieved economically, using a line of white paint over which a pencil is run. (It would be wrong to say that Mr Terry completed the whole of this repetitive task; a local assistant took over when he had established the principles.)

The linocuts derive from his years at the Architectural Association, before he had discovered Erith and Classicism; there, he belonged to a triumvirate of architecturally non-conforming, evangelical students — with Andrew Anderson and Malcolm Higgs — admirers, at that time, of William Morris, Eric Gill and Edwin Lutyens. The severity of black-and-white linocuts, which demanded hours of patient labour to complete, appealed to their austere sense of style.

In Dedham, Erith appreciated Mr Terry’s exceptional skill in reducing complexity to two dimensions — as Mr Terry now remembers: ‘He thought the economy was particularly suitable to Classical architecture.’ Linocut became the preferred medium of Erith and Terry’s annual contribution to the Royal Academy’s architectural room. Mr Terry’s partner, Eric Cartwright, now continues the office’s linocut tradition.

Mr Terry’s study, a place of mahogany furniture and Turkey rug, Piranesi engravings and linocuts, lies to the left of the front door; opposite is the dining room. Here, Mrs Terry had command of the decoration, creating a Pompeiian scheme from pigments mixed with seize. A Greek-key frieze was added under the cornice. Even the Terrys’ nanny was found faux-marbling the dado.

The flamboyant Venetian chandelier took up its place here, after falling down from its previous position (fortunately, it was possible to have replacement parts made in Murano). The 16th-century Mannerist painting of Esther and Xerxes (the iconography of which has been known to defeat both Catholic and Anglican bishops) was bought in the 1980s, from the proceeds of a sale exhibition of Mr Terry’s architectural drawings.

The drawing room and kitchen lie at the back of the house. Both have been architecturally enhanced by means of an architectural order: Corinthian in the drawing room, Doric in the kitchen. The tedium of setting out each pilaster by hand was reduced by drawing one on tracing paper and reproducing it as a dieline print on the office machine; these were then stuck to the walls and painted.

Between the columns are Baroque statues in niches. The frieze is lettered with the words from Psalm 97 Dominus Regnavit. ‘Lettering I find easy,’ says Mr Terry. It must have been satisfying to arrange the spacing so that the words Justicia (Justice) and Judicium (Judgment) should come over the fireplace.

As with the linocuts, visual economy is paramount. The whole scheme was created from a combination of only three tones: light grey, dark grey and white.

In the kitchen, the Doric order sits alongside dressers piled with colourful china. For many years, this was where family meals were eaten and the decoration of this room was also a family affair. Indeed, two measuring sticks have been hand-carved with the heights of growing children, together with names and dates, in the kitchen, a Stanley knife doing duty for the stonemason’s chisel to create an almost lapidary effect.

We go upstairs — more faux masonry, continued into the Regency lantern that lights the staircase — to the master bedroom, where the Tuscan order was painted when Mrs Terry was waiting to give birth to the Terrys’ fifth and youngest child, Sophie. After the happy event, the scheme was abandoned: the room was too busy to paint in.

A Drottningholm bedroom, after the chinoiserie Green Salon, with motifs by Boucher, was Mrs Terry’s creation; the figures were painted by son Francis, now an architect in his own right, but then at school. It was also Francis, at the age of 16, who conjured into existence a complete Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland room for his sisters. It remains as popular with the Terrys’ grandchildren as it did with its original occupants.

Many architects strive to make their houses a personal Arcadia, but the essence of Higham Hall is not the Olympian grandeur one might expect of such a notable Classical architect at the height of his profession. Instead, the organising principle of Classicism combines with a delight in making and the rewards of family life. The result is surely unique.

The best country house architects in Britain

Country Life has once again delved into its to update the list of the finest architects in Britain — an