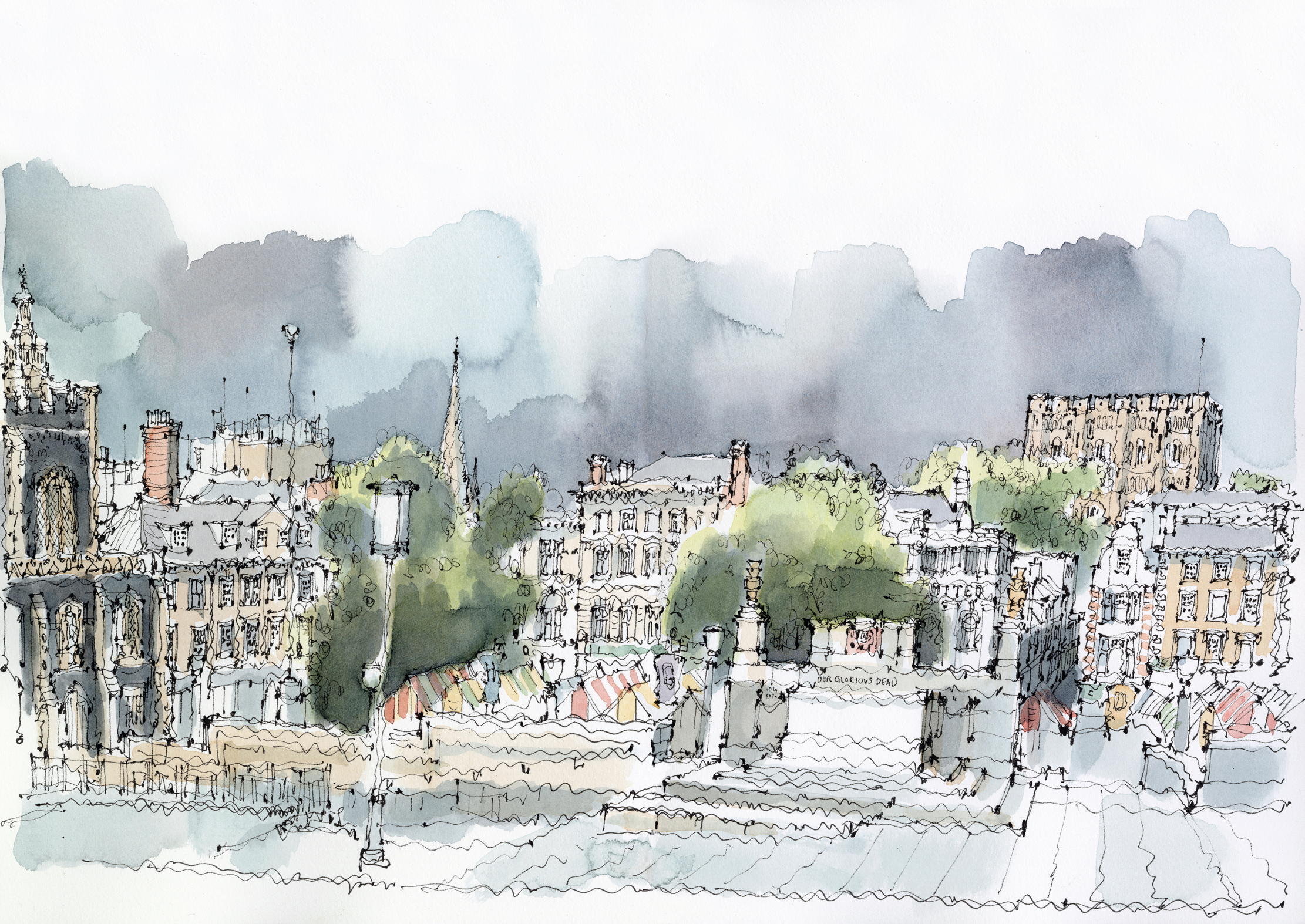

Ptolemy Dean: The magic that happens when you stop to draw a place, instead of just taking a photograph

A new book examines the streetscapes of our historic towns and marvels at what we can easily take for granted. Its author, Ptolemy Dean, encourages us to recognise their importance and considers what we can learn from them. Illustrations by Ptolemy Dean.

All illustrations ©Ptolemy Dean

In 1978, the amiable architectural historian and expert on traditional building materials Alec Clifton Taylor made his first appearance on television with an informative BBC series, Six English Towns, on the evolution of the featured places. It was so popular that two further series followed in 1981 and 1984. I can remember watching some of these programmes when still at school, cementing a fascination with towns that I have carried with me ever since. The shape, depth and perspective of streets and townscapes inspired me to start drawing them.

Unlike photographs, the process of drawing allows the key ingredients of a scene to be seen and digested despite the distracting elements of clutter, cars and signage. It also gives the opportunity to absorb the atmosphere of the place, hearing snatches of conversation and watch the world go by. The experience of drawing historic towns makes me conscious that they have something important to teach us.

With a new government keen to encourage the development of new housing, we need the inspiration of historic layout to understand and replicate the vital elements that constitute their outstanding wonder: great streetscapes. Go to any celebrated historic town and the streetscape seems to draw you into the centre without the need to refer to a map. The layout and texture of its streets make natural sense, and their scale and density offer an intense and exciting experience for those exploring and navigating around them for the first time. It is a complete contrast to the disorientation and bewilderment that can be felt in many modern housing developments. My new book tries to capture, through sequences of drawings, the way in which the principal streets of 26 historic towns reveal themselves to the pedestrian visitor.

Fig 2: The Westgate at Canterbury, Kent, frames a view into the historic heart of the city along St Peter’s Street.

Efforts have been made to try to reproduce some of the instinctive qualities of old towns in new developments, but it is easy for the effect to feel arbitrary or contrived. That’s because streetscapes are the combined product of topography and deep history. To decode their mystery, we need to understand both.

The Romans, the founders of our earliest planned, large-scale settlements, often sited them strategically. There were usually clear sight lines to surrounding areas for defence, good transport links for trade or easy access to the natural crossing points of rivers. They knew how to pick a good site. As the Romans were conquerors, they initially laid out their towns on military lines on a strict grid. The first four planned towns, what the Romans called ‘Colonia’, were garrison settlements established at Colchester, Gloucester, Lincoln and York from the mid 1st century onwards. Remarkably, in each place, not only is the line of the Roman walls still clearly legible in the street pattern, but fragments from the fortifications survive. Other regional capitals known as ‘Civitas’ were also created by the Romans, which were not initially walled. These gained protective encircling walls later on in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when external conditions demanded defences. Exeter, Canterbury and Chichester are all examples. As these towns had already been established, the encircling walls had to enclose what had already been built and, therefore, could not follow a regular rectangular form. Already some of the picturesque unevenness that we now so enjoy was beginning to creep in. The massive medieval Westgate (Fig 2) at Canterbury sits on the site of a Roman predecessor.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the early 5th century, the Roman towns were largely abandoned and the population scattered. One can imagine these derelict places, centuries later, where only the substantial walls, with their gateway entrances standing, encircling the rough and overgrown ground of long-collapsed and ruinous buildings. When these places began to be re-occupied by Anglo-Saxons four or five centuries later, the newly remade streets would naturally start at the old Roman gates where the old walls would allow access. Then, the course of new streets might meander around the rubble of fallen masonry, creating curved streets and deviations from the old Roman grid, as can be seen at Winchester in Hampshire. In some places, the ruins were so substantial that there is a ‘jolt’ in the streetline, which creates a closed vista that contains the street most attractively. Such is the case in Chichester, West Sussex, where the crossing point of the principal streets is staggered, closing views and making space for the later addition of an elegant market cross (Fig 3).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fig 3: The staggered street line of Chichester in West Sussex, marked by the medieval market cross.

The sudden, massive upheaval of the Norman Conquest in 1066 had a transformative effect on many towns. At Norwich, the imposition of the Norman castle is known to have erased a whole quarter of the Saxon town. This castle now looks down on a large market place that only assumed its present size as part of early-20th-century improvements (Fig 7).

The Normans also founded new settlements, such as Richmond in North Yorkshire, where the town and castle are integrally laid out on top of the eponymous ‘strong hill’ above the steep banks of the River Swale. Together they encircle a huge central market place where the topography is easy to read (Fig 8). The Normans were great builders of churches and cathedrals, too, often replacing relatively modest Saxon predecessors with leviathans. These are often spectacularly positioned, filling street views and vistas. Lincoln (Fig 5) and Durham are the classic examples. It is unimaginable that these massive buildings — as with Norman castles — were not placed so as to impress themselves upon the town streets and the citizens that used them.

Fig 4: St Paul’s Cathedral, London, presides over the view along Fleet Street.

The ongoing wealth of English towns during the Middle Ages is reflected by numerous parish churches. Even a relatively modest town such as Stamford in Lincolnshire yields no fewer than five. Their towers perform like cameo actors as they emerge and disappear in kinetic views as the visitor walks through the town. It is nothing short of miraculous that so many of these vital buildings survived the destruction of the Reformation during the 16th century and the Civil War that followed it in the 17th century. It should be said that, between these two episodes, the cartographer John Speed published maps of 52 English towns in The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain (1611).

Although some of his plans are copies of those made by others, Speed’s maps provide a vital and insightful first survey of how our towns must once have appeared. These plans often record features that have subsequently been swept away, notably during that great era of road widening from the late 18th century, when numerous medieval town gates, market crosses and other perceived ‘obstructions’ to traffic were demolished. The surviving city gates of York indicate the character of what has been lost, and it is clear how in the locations where town walls and gates do survive, they bestow a sense of distinction on the areas that they define.

Fig 5: The west front of Lincoln Cathedral beyond the precinct’s Exchequer Gate.

In Devon, Exeter contains a coherent 18th-century quarter where civilised red-brick Georgian terraces are arranged to overlook attractive communal garden spaces; a pattern more famously associated with the expansion of Bath. In both, the emphasis of new developments is centred on the creation of proper streets where vistas are deliberately controlled and framed. Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Bath was the way that the new developments were re-connected to the medieval city centre by new streets that cut through the fabric of the old town.

Stall Street in Bath, for example, was a medieval street that was widened and framed by a shallow crescent to celebrate the side-street entrance to one of the former Roman Baths, as well as defining the precinct to medieval Bath Abbey (Fig 1). A no-less-visionary remaking of New castle upon Tyne took place in the early 19th century. This included the erection of a substantial stone column to the memory of Earl Grey, a local resident, visually and physically marking the climax of a new streetscape route that reorganised the whole city (Fig 6).

Fig 6: The majestic curve of Grey Street, Newcastle, constructed during the reorganisation of the city, which culminates in the column erected in 1838 to the 2nd Earl Grey.

Builders of the later 19th century never shied away from enhancing existing streets with ornamental and exuberant buildings. In Essex, the Colchester town hall campanile, only completed in 1902, was deliberately made sufficiently tall so that it could dominate the hilltop composition from a key river crossing below. The ancient processional route between Westminster and St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London is lined by splendid Victorian or Edwardian buildings for much of the way (Fig 4). We take these sorts of buildings for granted, but we do so at our peril, especially given the generally banal architectural contribution that has been provided from the mid 20th century onwards. In all too many post-war town centres, street lines have been ignored, motor traffic prioritised and box-like, flat-roofed buildings arranged with little relationship either to each other or their surrounds. These areas no longer offer that instinctive and reassuring sense of enclosure and protection that had been ingrained in town development before this time.

Fig 7: The spreading market place of Norwich, Norfolk, set against the backdrop of William Rufus’s keep on the castle mound.

In looking forward, and learning from the past, there is a sense that in each and every town, there was, at the outset, a decision to select the right site to create the place. Standing in Westminster Abbey today or, indeed, at the centres of any one of the historic towns surveyed, it’s salutary to think that someone once chose these sites as the right place to build. That decision was based on considerations that we can now but imagine, but it is clear that topography was crucial. Nowadays, building sites are all too often merely areas of a plan that are hatched in ‘for housing’ and then passed on to commercial developers who lay them out to suit nearby traffic arteries and to maximise the number of ‘units’ that can be fitted into them. The process becomes a graphics exercise rather than one where a site is physically selected as the heart of a new place.

If a study of historic English streetscapes teaches us anything, it is perhaps the need to remember that vital link between strategic practicality and making the best of whatever existing natural landscape topography might exist. Only when that conjunction is achieved can the magic of a place be unlocked and a meaningful streetscape created.

‘Streetscapes: Navigating Historic English Towns’ by Ptolemy Dean is published by Lund Humphries (£45)

Fig 8: The approach to the market place in Richmond, North Yorkshire, up Frenchgate.

A new house in Hampshire by Cotswold-based architectural practice Yiangou.

The best country house architects in Britain

Country Life has once again delved into its to update the list of the finest architects in Britain — an

Credit: Shanks House, Somerset (©Paul Highnam/Country Life)

Shanks House: A model restoration of a magnificent Georgian home

The exemplary restoration of this magnificent house has reintegrated a complex building into a single and coherent modern home, as

Created for art: the Dulwich Picture Gallery, SE21

Seeing the light: The lasting legacy of Sir John Soane

For Sir John Soane, the tools of the trade included skylights, tinted glasses and mirrors, as much as classical motifs,

Ptolemy Dean is an architect, writer, television presenter and expert in the preservation of old buildings who since 2012 has been Surveyor of the Fabric at Westminster Abbey. His practice, Ptolemy Dean architects, specialises in conservation work and additions to historic buildings, and the design of new buildings in sensitive locations.