Plumpton Rocks, Harrogate: Heaven on earth

Recent restoration work has helped re-create a celebrated landscape garden crafted in the late 18th century around a dramatic gritstone outcrop, as John Goodall explains.

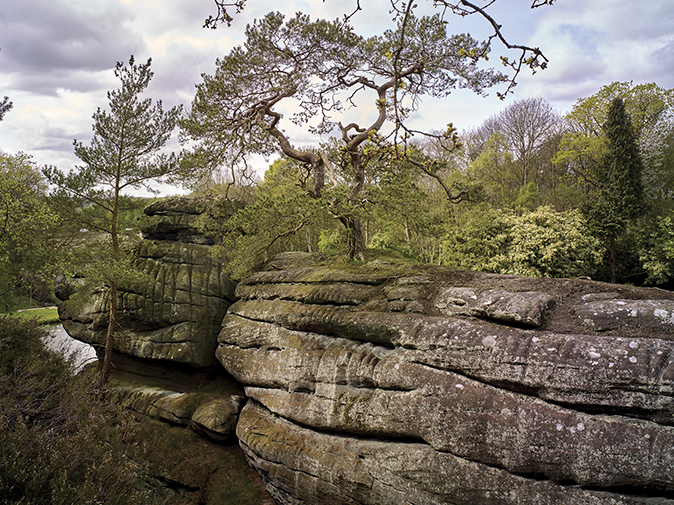

Plumpton Rocks is as unexpected as it is astonishing, a cluster of vast gritstone boulders that bursts through the undulating North Yorkshire landscape. This natural outcrop, which shares the geology of the more familiar Brimham Rocks, was transformed into a celebrated landscape garden in the 1750s and enjoyed considerable celebrity into the early 20th century.

Since the 1950s, however, it has almost completely slipped from the popular consciousness and when it was last written up in Country Life on February 13, 1992, it seemed to be vanishing altogether, threatened by Nature and a road scheme. That has now changed. A triumphant restoration completed in 2016 gives a modern audience the opportunity to enjoy its 18th-century grandeur once more.

The present garden was the creation of Daniel Lascelles, co-heir to a great West Indian fortune founded on trade and sugar. Having returned from Barbados, Daniel’s father, Henry, used his money to install the family in his native Yorkshire. Not only did Henry create the Harewood estate in 1739, but he also purchased parliamentary seats for himself and his sons. At Henry’s death in 1753, Harewood passed to the eldest, Edwin. Daniel, meanwhile, was compelled by the terms of his father’s will to invest one third of his inheritance in property. By this time he had already married and been divorced.

Daniel’s eye eventually fell on the Plumpton estate, a property held for nearly 700 years by a family of the same name. The Plumpton entail had recently been broken following the death of the last direct male heir in 1749. Consequently, in 1755, Daniel purchased the property, along with additional nearby land, for £33,563.

It’s tempting to imagine that Daniel was persuaded by the landscaping opportunities presented by Plumpton Rocks. Certainly, his first concern was planting and improving the grounds. He borrowed his brother’s steward, Samuel Popplewell, for the purpose and wrote to him on May 13, 1755 demanding to know if he had found ‘a proper person for looking after the Wood and taking care of the Nursery’.

By the autumn, the gardener John Banks was clearly in charge of the work at Plumpton. Banks seemingly remained here until he died in 1773–4, offering memorable tours of the garden.

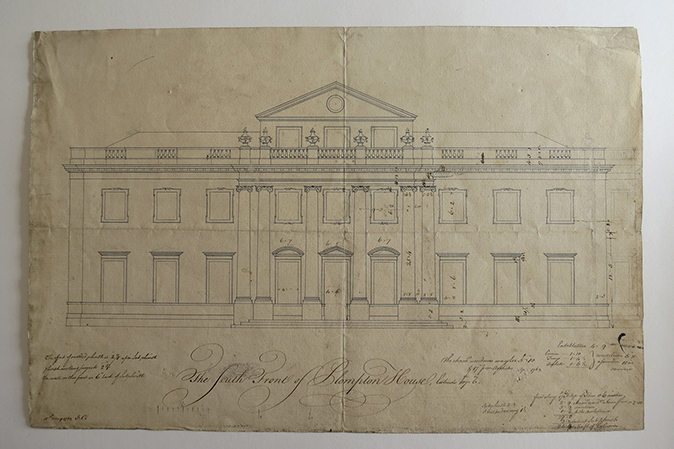

Meanwhile, plans were being laid for Daniel’s house. Again, he employed a figure involved, since 1753, in his brother’s works at Harewood, John Carr. Born into a family of masons, by 1755 Carr was clearly emerging as the leading architect in Yorkshire. The initial plan seems to have been to improve the existing hall at Plumpton. A crude sketch of the building by Samuel Buck in about 1720 shows an incoherent jumble of buildings incorporating a freestanding medieval tower.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Carr concurrently worked on the architecture of the new Plumpton estate. Drawing on his experience as a bridge builder, he provided plans for a boldy detailed dam to create a lake around the rocks in place of two medieval fishponds.

As originally conceived, the dam was to possess a central pyramid, but this feature was probably dropped for reasons of expense. Daniel, indeed, was proving a troublesome client. When there was confusion over the erection of a bell-tower on top of the grand new stables he wrote furiously ‘Lett a stop be putt to this turret, it is Just as I conjectured a vy Expensive Joke Ornament, and much to great for such a Building’. Happily for us, his instruction came too late.

Frustration and expense also eventually ended works to the old house. In 1761, Carr drew up plans for a completely new residence overlooking the new landscape garden and work began to that instead. Yet again, however, Daniel feared for the final cost. In 1762 he purchased the neighbouring estate at Goldsborough with its 17th-century house and directed Carr to begin improvements there. Work to the new house at Plumpton was then abandoned with ‘one wing covered in, but the center and the other only about half a yard high’.

Daniel did not, however, abandon his new landscape garden, nor his stable range, which he adapted as a banqueting house. Before the decade was out we have the first visitors' accounts of what the gardens were like. One discovered by Karen Lynch at the John Rylands Library, Manchester, gives Dorothy Richardson’s impression of Plumpton in August 1771:

‘The Gardens are uncommonly Romantic; and tho they are not large, appear so… an old Gardener betwixt Eighty and Ninety shows the place [presumably John Banks]… A Range of very large Earth fast Stones, and huge Rocks run along the Side of a Hill, amongst which are a great number of winding walks, with seats cut in the Rocks; which retire into abrupt Chasms, and in one place surround a beautiful lawn…Upon the top of one of the Rocks is a Chinese Seat, below the Rocks is a fine Lake, with some wild fantastic Rocks standing in it… No idea can be given of these Gardens by an description, they are particularly pleasing, but in a different style from any I ever saw.’

Richardson’s reference to a Chinese seat is intriguing because Chippendale supplied furniture for both Goldsborough and Harewood. Might the original benches in the garden, which survived into the 20th century, have been by him and in his Chinese style? Other visitors, such as Edward Witts in 1777, thought Plumpton as a whole bore ‘exact resemblance to a Chinese Garden’. It’s a quality that still strikes the modern visitor.

Daniel died in 1784, after which Plumpton was absorbed into the Harewood estate. It became a favourite spot for the family and their guests. Artists too came here and, in 1797, Turner painted two views of the rocks, his first commission in oils. He returned in 1816 and the sketches he made have helped with the restoration. As the 19th century progressed, more visitors came, in 1886 paying 6d for entry. The stable block became a tea room. Nevertheless, the spot maintained its magic and, on a visit to the rocks in the 1920s, Queen Mary is reputed to have described them as ‘Heaven on earth’.

In 1951, the connection of the landscape garden with Harewood was broken when Plumpton was sold to pay death duties. By a happy chance, the sale was spotted by the present owner’s father, Edward de Plumpton Hunter, a descendant of the Plumpton family that had owned the property from the Middle Ages until 1749. He was a 24-year old solicitor with a passion for family history. Through the intercession of Princess Mary (Lord Harewood’s widow), the landscape garden of 35.5 acres was separated from the main lot. He was then able to purchase it for £5,000, borrowing some money from relatives to do so.

Meanwhile, the other estate buildings constructed by Carr were sold off and converted to residential use. Plumpton Hunter himself took up residence in a pair of gardeners’ cottages in the walled garden. He also bought the part of the stable block that had previously been used as a tea room for visitors to the garden. The purchase protected the garden from encroaching development, but it also left it relatively isolated, without any surrounding parkland. The rocks and the lake, of course, survived, but the latter gradually deteriorated. Rhododendron and weed trees invaded the woodland and the lake began to silt up. Then, in 1977, after the tragic death of a step son in a road accident, he and his wife moved to Northumberland.

Their son Robert Hunter, the present owner, had delighted in the rocks as a child and decided to try and take the landscape garden in hand. In 2010, shortly before his father’s death, Mr Hunter bought 36 acres of land immediately to the east of the lake, rocks and woodland that he soon afterwards inherited from his father. The purchase re-established the connection of the landscape with the park and Carr’s buildings.

Such was the deterioration of the site that, in 2012, Plumpton Rocks was placed on the Buildings and Landscapes at Risk Register by English Heritage. This listing was to prove enormously helpful in restoring the garden, unlocking sources of funding that had not previously been available. In particular, with the help of Margaret Nieke of Natural England, a successful application was made to place the rocks in Higher Level Stewardship. A series of investigative reports followed to prepare the way for the restoration of the garden landscape. The work progressed in stages over three years.

Most of the parkland to the east of the rocks had been ploughed up in 2014. With the evidence of estate maps, Mr Hunter re-seeded this area as grass and re-planted it with 80 trees – estate records at Harewood identified the correct species to plant. The following year, he began to implement a woodland management plan, clearing rhododendrons and weed trees while introducing species such as oak, holly and yew in their place. New benches had previously been commissioned for the 18th-century niches cut in the rock. They were designed and made by pupils of Ampleforth College.

During the winter of 2015–16, work went ahead to dredge the lake, with the intention of re-creating the 18th-century views across it. This monumental task involved the removal of 120 trees and huge quantities of silt, notably in the creek and the north end of the lake. The engineering consultant AECOM, with the contractors Fox, completed the work to time and to budget, revealing for the first time in 150 years the full extent of the 18th-century lake and its two tiny islands as depicted by Turner in 1797.

For reasons of economy the silt had to be deposited in the parkland rather than removed from the site altogether. One heart-stopping moment was the apparent discovery of Anglo-Saxon artefacts in the area that the silt was going to be deposited. Happily, on proper inspection, the artefacts turned out to be modern.

By now the funds for the restoration were exhausted. Another grant from English Heritage, however, generously matched with £30,000 from the Country Houses Foundation, allowed for the final piece of the jigsaw to be completed. Carr’s dam remained overgrown and in a state of collapse, but with the oversight of the conservation practice that had advised on the whole project, Donald Insall Associates, the whole was repaired, replete with its six giant balls of stone. Where possible the original stones were rescued and re-used.

The entire project was completed in July 2016 and, for a small entry charge, the garden is once again open to visitors. This is not a place, however, for those who wish for the indulgence of a tearoom or paths of hard standing. Rather, it remains a romantic place to wander and explore. After years of gradual decline, magic has returned.

Visit www.plumptonrocks.com for further information

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.