Palaces on the sea: The story of the father of promenade piers

Eugenius Birch, father of the promenade pier, was born 200 years ago. Kathryn Ferry considers the life and remarkable legacy of this outstanding figure.

Every year, the World Monuments Fund places 25 heritage sites from across the globe on a watch list. The aim is to focus attention on the unique cultural importance of these places, as well as highlighting their vulnerability. In 2018, Britain is represented on the list by the three pleasure piers at Blackpool, ‘the finest assemblage of seaside piers’.

The timing could not be better, because this year also marks the bicentenary of Eugenius Birch, designer of Blackpool’s first pier and the most prolific pier engineer of his generation, who was born on June 20, 1818. To enthusiasts, Birch is the father of the iron promenade pier, a man whose talent for innovation helped transform the Victorian experience of visiting the seaside and whose legacy can be seen in the iron limbs that still strike out around our coastline. His best-known work is probably Brighton’s West Pier, which, despite its sad demise, maintains an almost iconic status. The newly rebuilt Hastings Pier was originally his, too.

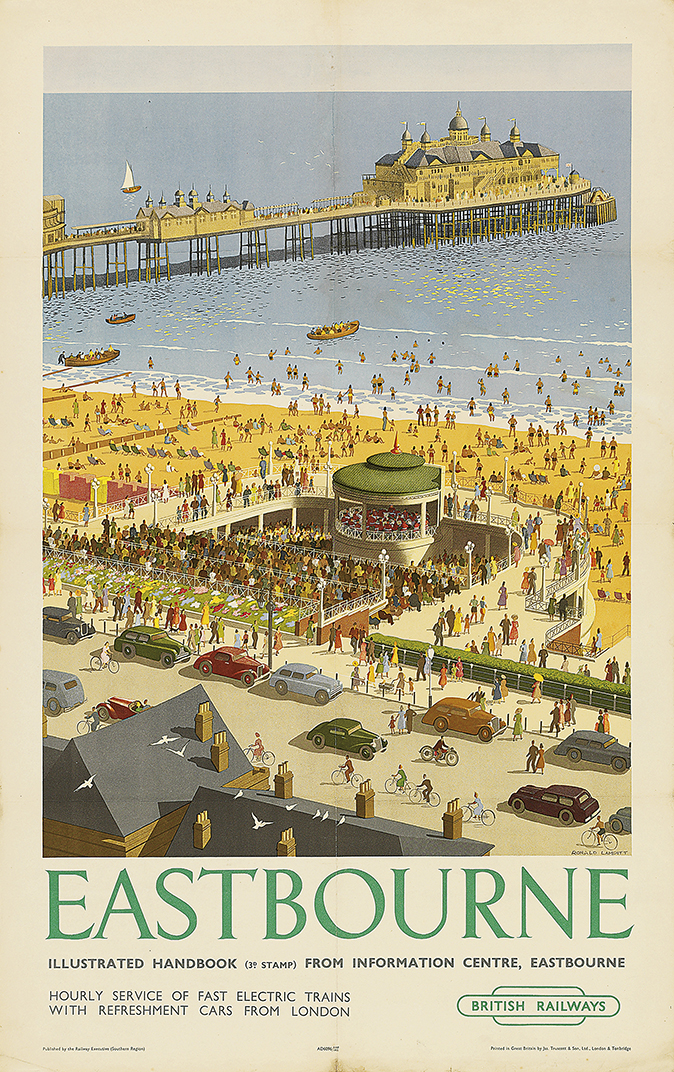

During the 1860s and 1870s, an average of two piers were built around the UK coast every year, a large proportion of these by Birch. In 1866, the Brighton Gazette stated: ‘He is looked upon as the first engineer in England for sea works of this description, and… has no less than 18 piers either finished or in progress round the coast.’ His final tally was to include Deal, Blackpool North, Eastbourne, Birnbeck at Weston-super-Mare, Aberystwyth, Lytham, Scarborough North, New Brighton, Bournemouth, Hornsea and Plymouth. He also made proposals for piers at Llandudno, Bray in Ireland, Paignton, Hove, Torquay and West Worthing.

However, before all of these came Margate Jetty. In 1852, Eugenius was in partnership with his elder brother, John Brannis Birch. Together, they submitted plans for a new landing stage at Margate, to be made of iron. From the 15 proposals submitted, theirs was unanimously chosen as the winner.

Up until that point, piers had been built of wood. Historically, their principal function was the landing and embarkation of goods and passengers. In July 1814, however, a pier opened at Ryde on the Isle of Wight that was designed with the additional purpose of providing holidaymakers with a place on which to walk. It ushered in a new breed of promenade piers, which would include a small number that used suspension technology to carry the deck, most notably Brighton’s Chain Pier of 1823.

Birch was familiar with this structure, having been to school at Brighton, yet his inspiration for Margate Jetty came from elsewhere. The clusters of iron columns that would hold up his pier were to be placed into the seabed using the screw-pile technique patented in 1833 by Irishman Alexander Mitchell. Employed by Mitchell to construct offshore lighthouses, this method had proved itself in the marine environment. The Birch brothers had themselves made innovative use of iron screw piles in the construction of Kelham Bridge on the River Trent in 1850 and were also looking at new applications for the technology.

In 1853, they were granted a patent for an invention to improve the laying of underground drainage pipes, by means of a screw tunnelling machine. This knowledge then informed their designs for Margate Jetty. The result was a structure 1,240ft long with a promenading area of 30,000 superficial feet. Unfortunately, as The Builder pointed out after it opened in 1855: ‘Whatever may be its mechanical sufficiency, the ugliness of the new pier is unquestionable.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Due to its experimental nature, Margate Jetty lacked the finesse of later Birch designs. Although structurally ground-breaking, it still looked like a railway bridge.

By the time his second pier opened at Blackpool in May 1863, Eugenius had developed his ideas into a more distinctive pier vocabulary. He not only succeeded in enhancing the foreshore – prompting The Builder to declare that Blackpool Pier ‘is an elegant structure and possesses great lightness of appearance’ – he also made new provision for the needs of the promenaders, thereby increasing the returns for shareholders in the pier company.

As they strolled above the waves, holidaymakers could stop off at one of the 10 kiosks to buy a book or some confectionery; those wishing to linger could make use of the built-in seating that ran continuously along the pier’s main girder.

In the opening year, 275,000 people paid for entry to Blackpool North pier. In 1864, that figure rose to 400,000, going up again in 1865 to 465,000, allowing shareholders to enjoy a 12% dividend on their investment.

With such evident popularity and potential for profit, piers became the must-have accessory of every aspiring seaside resort and Birch’s services were in high demand. Although the business partnership with his brother had come to an end when John was admitted to a lunatic asylum in 1860, Eugenius seems to have been among that breed of Victorian engineers and architects for whom the technological possibilities of their age acted as a spur to enviable productivity.

Competition between resorts was so fierce that Birch was able to make significant innovations. When his suggestions for replacing Brighton’s Chain Pier were rebuffed, he worked with a new company to design a modern rival known as the West Pier. At the pier head, furthest from the shore, he widened the deck to create a large open space, at the four corners of which were octagonal ‘houses’ designed as separate ladies’ and gentlemans’ ‘lounging’ and refreshment rooms.

Even more novel were the windscreens, designed with back-to-back seats separated by plate glass to keep the wind away without obscuring views from the pier. This helped to attract people outside the summer season, an instant boon given that the pier’s opening was delayed until October of 1866.

In a justly proud article, the Brighton Guardian described it as a place of wonderful escape: ‘Londoners know what it is to enter one of the parks. The streets are shut out, the roar and the cries can be dimly heard… Just the same sensation is felt when the body of the New Pier is reached. There are the jangle of the shingle and the cries of the boatmen, and the hum of conversation from the beach below; and there is the noise of the town and carriage traffic behind, but every step deadens the sound, and gives the visitor the impression that he is rather on the deck of some large and elegantly-fitted passenger vessel than on a “longshore” erection. In this feature we fancy the New West Pier is unapproachable.’

Six years later, however, the West Pier’s pre-eminence was challenged by another Birch-designed pier at Hastings. Here, the large pier head was strengthened to enable the erection of an iron-and-glass pavilion, capable of holding 2,000 people, which Earl Granville noted, in his opening speech on August 5, 1872, had already been christened the ‘Palace on the Sea’.

It was to set an important precedent both for piers as entertainment venues and for the Oriental style of its architecture. At the four corners were miniature domes suggestive of Brighton’s Royal Pavilion and wrapped around the exterior was a sheltered verandah that was inspired by the Alhambra in Spain. This was the perfect place for such exotic fancy, allowing concertgoers the sensation of crossing the sea to another world. Its success meant that it was widely copied at other resorts.

As early as January 1873, an extraordinary meeting of the Eastbourne Pier Company was called to discuss proposals for adding a Birch-designed pavilion to its pier. As the pier itself had only been completed to his specifications the previous year, there was little appetite for extra expenditure, but the sense that the endeavour was already out of date is clear.

At Blackpool, the erection of the Central Pier, as well as new venues including the Winter Gardens and Theatre Royal, provided compelling impetus for upgrading Birch’s original North Pier to retain the custom of well-to-do visitors. Plans to lengthen and widen the pier were announced in 1874 and, on two new wings at the sea end, Birch designed a bandstand and an Indian-style pavilion based on the Hindu Temple of Binderabund (now Vrindavan). Costing £40,000, these improvements opened to great acclaim in 1877. Together with the two Aquariums he built at Brighton and Scarborough, these pier pavilions demonstrate that Birch was a talented designer as well as a skilled engineer. Indeed, there was a great variety in his pier buildings that included Byzantine structures on New Brighton Pier and Gothic toll houses at Bournemouth.

According to his obituary: ‘At a very early age, he showed considerable mechanical and artistic talent, and was rarely seen without a pencil in his hand.’ Surviving drawings confirm the beauty of his draughtsmanship, but, regrettably, they are few in number.

Even more regrettable is the fact that there is no known portrait of Birch, an astonishing circumstance given his fame and the spread of photography and print media during his lifetime. Although this has helped make him a notoriously elusive figure, National Piers Society member Martyn Webster has recently made important new genealogical discoveries that deepen our understanding of Eugenius the man.

In 1842, he married Margaret Gent, the daughter of a silk manufacturer from Congleton in Cheshire, who also happened to be his sister-in-law by marriage. The couple remained childless, but, in 1879, Birch did become a father when his mistress, Marian Morris, a niece of his wife’s, gave birth to Eugene, the first of their two children. The second, called Ethel, was born in 1881 when Eugenius was 63.

In spite of his advancing years, Birch maintained an active professional practice. During the early 1880s, he was building a pier at Plymouth, designing a huge extension to Brighton Chain Pier for the erection of a theatre complex, projecting a pier at West Worthing and a railway connection from Chelmsford to Southend Pier.

All this was curtailed by an accident that damaged his ankle to such a degree he was later forced to have his leg amputated to the thigh. Although the operation appeared to be successful at first, complications led to Birch’s death on January 8, 1884.

He left behind an impressive body of work and it is not too strong to say that the piers designed and engineered by Birch had a major impact, transforming vast stretches of our coastline into fully fledged seaside resorts. Joseph Phillips, who worked under him as contractor for Ilfracombe Pier and Harbour, said, in 1873, that ‘Mr Birch was a gentleman who could command, if they could give it, the admiration of the very fishes of the deep’.

Given that recent surveys show a walk on the pier remains the most popular activity with visitors to the British seaside, it seems we all have something to thank him for.

Acknowledgements: Martyn Webster, Anya Chapman, Tim Phillips, Fred Gray, Martin Easdown and Carl Carrington

Orthopaedic shoe-making: The bridge between architecture and podiatry

John Goodall meets Bill Bird, who, having studied architecture at the Bartlett, now makes orthopaedic shoes.

Jason Goodwin: ‘Memories fade. Gavin was right: buildings outlive us all and they’re each memorials. They should not be allowed to disappear’

Our columnist remembers Gavin Stamp, the architectural critic, historian and campaigner.

The saving of Mount Grace Priory: A ruin revived in Arts-and-Crafts style

The saving of Mount Grace Priory in North Yorkshire is a fascinating tale of far-sightedness, persistence and determination. Gavin Stamp

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher