Oxford's forgotten history as the capital city of Britain

During the Civil War, Oxford briefly became Charles I’s capital. Simon Thurley explains how the city was fortified and the university adapted to accommodate the Court.

In 1644, the Royal Mint struck a unique silver crown coin. It showed Charles I mounted on a warhorse bestriding a detailed panorama of the City of Oxford (Fig 2). Never before had an English city been depicted on the coinage of the land. This accolade was awarded because, for 3½ years between October 1642 and its surrender to Parliamentarian forces in April 1646, Oxford was England’s capital city.

Charles I had left London in 1642, abandoning it to Parliamentarian forces and, after his humiliating defeat at the battle of Edgehill, he decided to regroup in Oxford, a defensible city with a long history of loyalty to the Crown and a place he regarded suitably magnificent to host the Court.

Oxford during its time as the British capital

- Stephen Conlin’s reconstruction of the fortifications of Oxford in 1644 is largely based on the plan — probably never fully realised — drawn up by the military engineer Bernard de Gomme and the fortifications are shown in relationship to the modern city. The areas probably flooded when the river was dammed are shown in a light blue tint.

- Many of the buildings used by the court and offices of state still survive. These include the King’s Lodging’s in Christ Church (1). His servants occupied houses along St Aldate’s (2) and Pembroke (3) became the lodging of Secretary of State Sir Edward Nicholas and numbers of other senior court officials.

- The Queen was lodged with her immediate servants in Merton (4), while Corpus Christi (5) was occupied by John Ashburnham, Treasurer and paymaster of the army. Oriel (6) became home to Lord Treasurer, Francis Cottington, as well as the Dean of the Chapel Royal and 35 other royal servants and officers. It also served as the office for Mercurius Aulicus, the mouthpiece of royalist propaganda.

- Parliament occupied the Schools and Convocation House (7) and Lincoln the Exchequer (8). There were arms stores in New College (9), Brasenose (10) and All Souls’ (11) and the castle (12) served as a prison.

When the war-battered monarch, with his army and Court, arrived at the gates of the city, he was no stranger to it. He had been lavishly entertained there in 1636 by Archbishop Laud, who was then vice-chancellor of the university, and he had lodged in the Dean’s lodgings at Christ Church. Statues of the King and Queen (Fig 3) dignified Laud’s new Canterbury Quad in St John’s College.

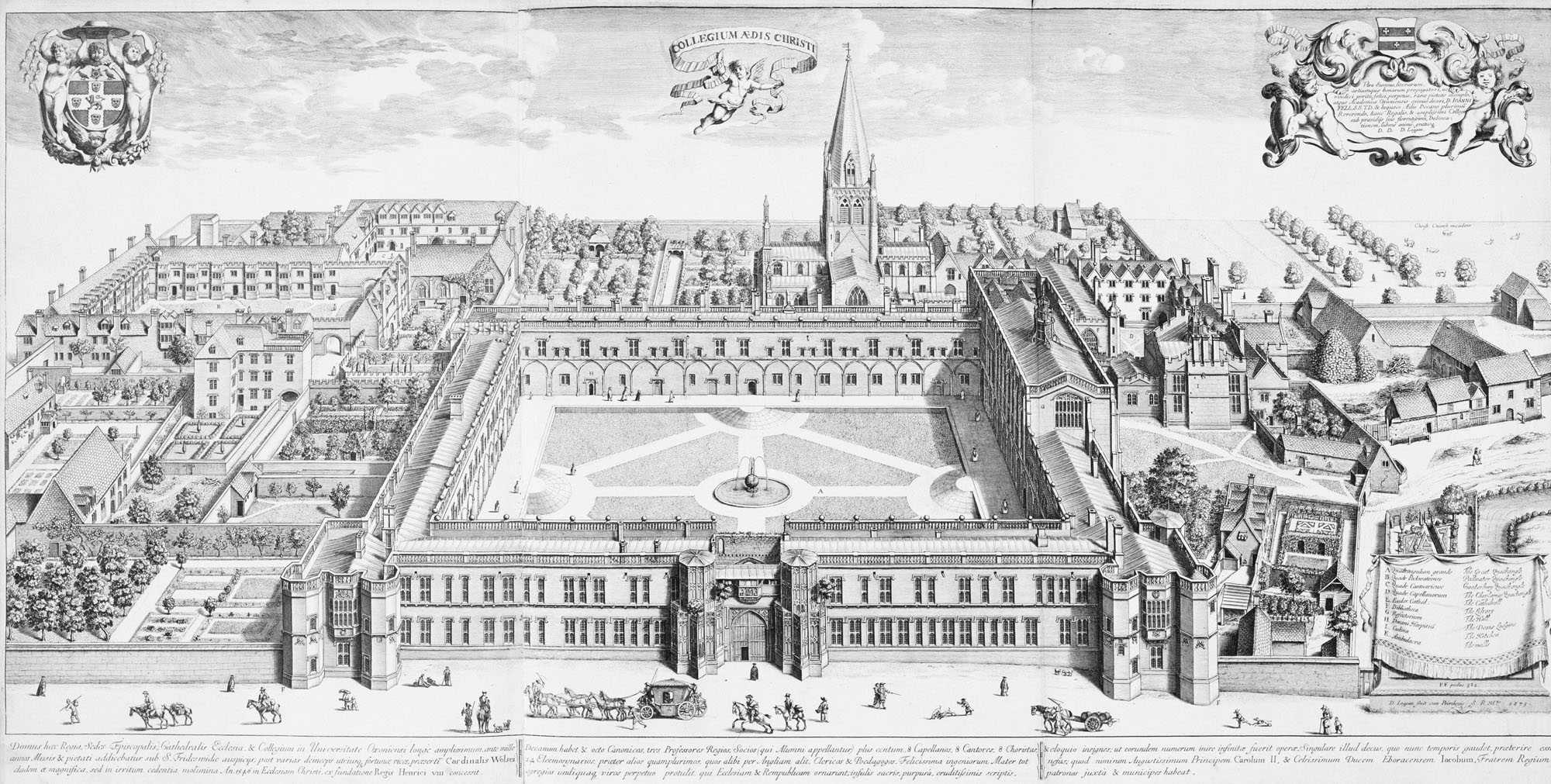

Christ Church had been founded by Cardinal Wolsey and was intended to be the largest college in Oxford or Cambridge, with a great cloister flanked to north and south by the hall and chapel (Fig 8). The scheme was interrupted by Wolsey’s death in 1530 and, although the hall, the most magnificent in Oxford, was completed, the great cloistered quadrangle it formed part of was only half built and the chapel barely begun. Instead, the partly dismantled priory church became the chapel. But not for long. The episcopal reorganisation that took place after the Reformation saw a new diocese of Oxford formed and the chapel become Christ Church Cathedral with its own dean and chapter.

This combined arrangement of college and cathedral was — and remains — unique, but what made it even more unusual were the provisions in the founding statutes of the college that specified it was to be used as a residence by the monarch when they were in Oxford. So, when the King arrived in October 1642, he settled into a royal residence with which he was familiar.

But this was no ordinary progress visit, because the King was accompanied by an army, the Court and hundreds of dispossessed, penurious or simply frightened royalists of all classes. Anybody with an official reason to be there was billeted on townspeople or in the colleges; everyone else was ordered to leave.

Householders were paid an allowance of 3s 6d a week for feeding a soldier and colleges charged their guests for board and lodging, rather as they did students. The pressure on accommodation was acute. In 1643, Ann, Lady Fanshawe, complained that ‘from as good house as any gentleman of England we had come to a baker’s house in an obscure street, and from rooms well-furnished to lie in a very bad bed in a garret’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The King moved directly into the Dean’s lodgings at Christ Church. These rooms are still occupied by the Dean and, before the mid-19th-century alterations of Dean Liddell (who was enriched by the profits of a Greek dictionary he compiled), had been little altered since the 17th century. Enough original work survives to work out the plan of the rooms in Charles I’s time. On the ground floor was a great hall and two parlours and, next to them, a kitchen and larders. The stairs to the first floor rose to a gallery off which was, in 1642, a room described as the presence and privy chamber — a single room serving both functions. Further south were three more rooms, one was the withdrawing chamber and the southernmost was the royal bedchamber; next to this were the backstairs linking the private rooms with the kitchens and service rooms below.

The rooms, although smaller in number than was usual in a royal house, were well lit and overlooked the Dean’s private garden, onto which the ground-floor parlours opened. They were furnished with tapestries, textiles, plate and other furniture from the royal wardrobe. Some items were sent from London, including clothes, drugs, drink and saddlery, but most furnishings were in the King’s vast baggage train that had accompanied him, as if on progress.

Although Archbishop Laud had characterised Christ Church as having ‘many fair lodgings for great men’, there was not enough space to accommodate all the offices or officers of state let alone the court. To the east of Christ Church were two colleges that were contiguous, Corpus Christi and Merton; across a narrow lane was a third, Oriel, and all three were effectively absorbed into the royal residence (Fig 6).

After Queen Henrietta Maria joined the King in July 1643, she was given lodgings in the 15th-century Fitzjames gateway at Merton (Fig 1, top). It was directly adjacent to Fellows Quadrangle, one of the most modern in Oxford, completed in 1610, and adorned with James I’s arms — in here was placed the Queen’s household. In order to link Merton and Christ Church, doorways were cut in the garden walls either side of Corpus Christi and a gravel path laid between them. At Corpus lodged John Ashburnham, Treasurer and Paymaster to the army, who was visited there by both the King and his sons, the bursar tipping the royal trumpeters and footmen who accompanied them.

Oriel College had been entirely rebuilt in the early part of Charles I’s reign and adorned with a large statue of the King over the hall door. The college became home to the Lord Treasurer, Francis Cottington and the Dean of the Chapel Royal, Richard Steward, as well as 35 other royal servants and army officers, although Oriel’s most important role was perhaps as editorial office for Mercurius Aulicus or The Court Mercury, the newspaper published in Oxford that became the mouthpiece of the Royalist cause.

Although the ordered cloisters, quads and gardens of Christ Church, Corpus and Merton might seem to have been a perfect royal enclave, they were also a war zone. Oxford was a walled city, but the Royalists realised that the medieval walls, even strengthened and supplemented with modern bastions and emplacements, would be no match for the New Model Army. The town lay on a spit of land between the rivers Isis and Cherwell, so, by strategically damming these, the low-lying meadows became impenetrable lakes, leaving only the northern defences to be hastily refortified by conscripted labour. One observer saw ‘the scholars night and day gall their hands with mattocks and spades’ in the service of the defenders (Fig 4).

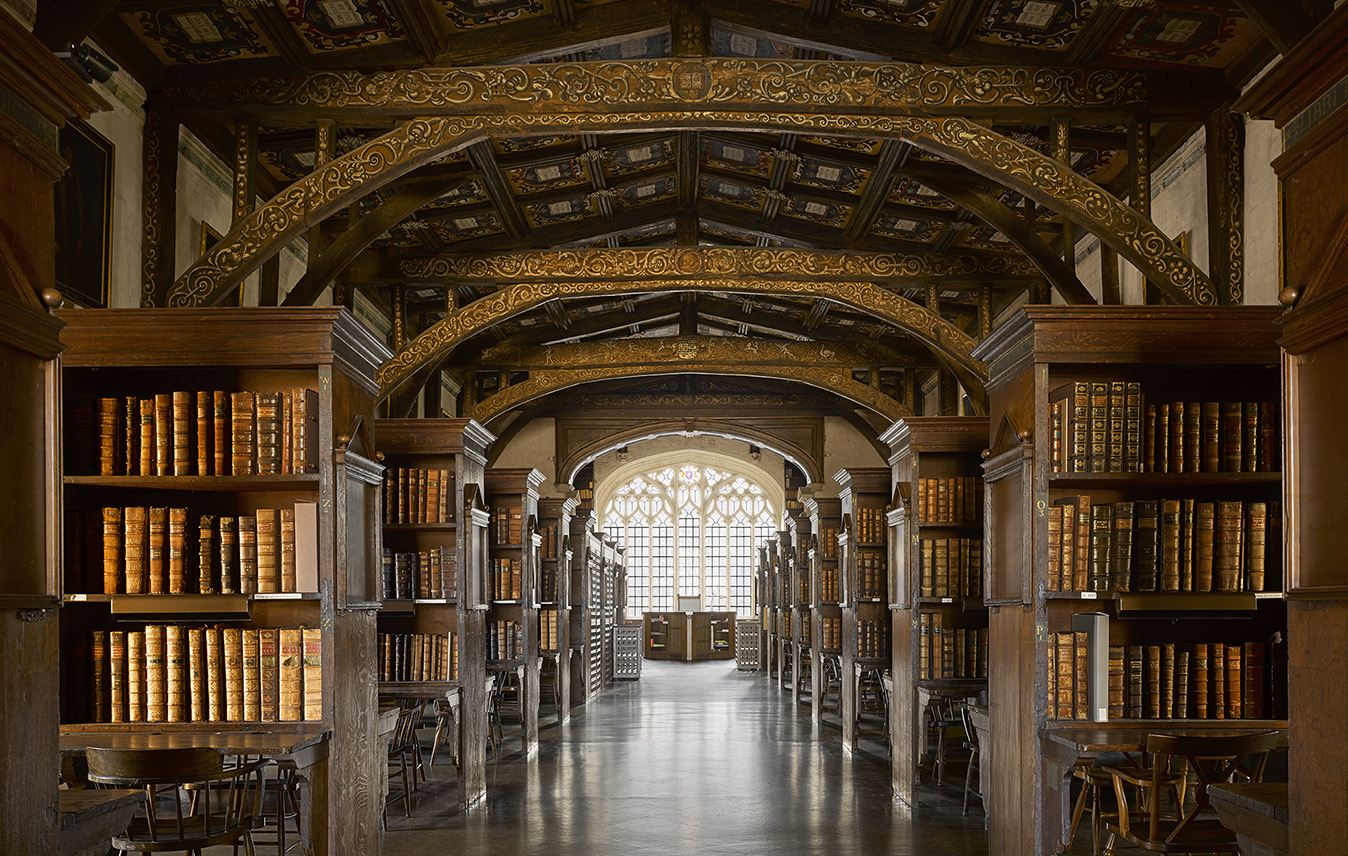

A tower on the town wall at Merton was cut down for a gun platform covering the flooded Christ Church water meadow; a magazine was set up at New College (Fig 9); an artillery park at Magdalen College Grove; and a cannon foundry at Christ Church. In the Schools building, small arms were repaired, drawbridges manufactured and armour and uniforms stored. Powder, meanwhile, was prudently milled on the outskirts of the city.

Summer was the campaigning season and King and army were in the field, but, as the Court retired to Oxford in the winters of 1642–43, 43–44 and 44–45, Court life became almost normal. The Royalist army officer Sir Henry Slingsby described the King’s daily routine in 1644: ‘He kept his hours most exactly, both for his exercises and for his dispatches, as also his hours for admitting all sorts to come to speak with him. You might know where he would be from any hour from his rising, which was very early, to his walk he took in the garden, and so to chapel and dinner; so after dinner, if he went not abroad, he had his hours for writing or discoursing, or chess playing, or tennis.’

The maintenance of a magnificent Court and state etiquette was as important to the King as the military effort. For Charles to be visibly King and to be afforded due deference was crucial, not only to his own dignity, but to the dignity of his office. The fiercely loyal Lady Mary Stafford got Parliamentarian passes to make three journeys from Oxford to St James’s Palace and, on one of them, succeeded in bringing to Oxford a mass of jewels and the King’s crown; the latter he was subsequently able to wear on major feast days in the cathedral. The Oxford Court was no ramshackle compromise, it was conducted with deliberate regality and magnificence.

As the ceremonial side of the King’s life was upheld, there was no neglect of pleasure. Charles hunted with his own pack of hounds in the royal park at Woodstock and, in poor weather, he played tennis with the Prince of Wales, Duke of York and Prince Rupert. There was a tennis court at the back of Christ Church near Oriel and, in November 1643, the King asked the Master of his Robes to send a servant from London to Oxford to bring a bolt of taffeta and ‘two pairs of garters and roses with silk buttons’ to make him a tennis suit.

In 1643, the King issued orders for all royal servants to join him at Oxford. This was the prelude to an attempt to relocate the central organs of the state to his new temporary capital. The Chancery, Exchequer and the courts of law were all ordered from Westminster to Oxford, where they were set up in colleges and university buildings. Parliament had taken control of the Mint at the Tower of London and the King had initially established a mint in Shrewsbury using his own plate and Welsh silver to mint coin. In January 1643, the Shrewsbury mint was ordered to Oxford and set up at New Inn Hall (the site of St Peter’s College). The following January, the King called Parliament to Oxford and 83 peers and 175 MPs attended him in the hall of Christ Church for its opening. Later they took their seats — the Commons in the Convocation House (Fig 5) and the Lords in the upper schools.

By the beginning of 1645, Oxford was starting to resemble Westminster in the intensity of government activity. But it was a desperate cause. After losing the battle of Naseby in June 1645 and surrendering Bristol, it became clear that the war was lost and, on April 27, 1646, the King rode out of Oxford disguised as a servant and accompanied by three attendants, abandoning his temporary capital, his cousin Prince Rupert and his young son, the Duke of York.

On June 25, the keys of the surrendered city were handed to Gen Fairfax who, with the other senior Parliamentary officers, entered and made for Christ Church. Prince James, Duke of York, remained in the Dean’s lodgings. One by one, they kissed the 12 year old’s hand; only one of their number knelt at his feet as they did so.

That man was Oliver Cromwell. Even in the humiliation of defeat, the magic of monarchy was alive.

A grand Devon country house where Oliver Cromwell officially began the English Civil War

The grandiose Chanters House, in Ottery St Mary, Devon, was the place where Oliver Cromwell declared the Civil War and

How Oxford University's buildings evolved, and how its 'chiefest wonder' came into being

'Where is the University?' is the most common tourist's question in Oxford. The answer is rather complicated.

New College, Oxford: The 650-year story of the college that dreamt it was a palace

John Goodall looks at New College, Oxford, the most widely copied university college in England, a building inspired by a

Oxford Street: How a Roman road evolved via public hangings into the most famous street of shops on the planet

To coincide with the publication of a definitive new study of Britain’s most famous retail destination, Andrew Saint looks at

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life