'One of the great landmarks of the Sussex coast', finally finished some 156 years after work was started

John Goodall looks at the recent completion of the chapel of Lancing College, one of the great landmarks of the Sussex coast. Photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

Lancing College Chapel was begun in 1868 with the intention that it should be one of the defining landmarks of the Sussex coastline. That ambition — it claims today to be the fourth-tallest ecclesiastical building in the British Isles — would in the ordinary run of things surely have doomed it to incompletion and abandonment. There was nothing ordinary, however, either about this astonishing building or the man who conceived it, clergyman Nathaniel Woodard. Construction has continued in fits and starts through several changes of design and the chapel was finally completed, after 154 years, on April 23, 2022, with the dedication of a new western porch designed by the architect Michael Drury.

Woodard was born in 1811, the ninth of 12 children of an Essex farmer, and absorbed a strong religious devotion from his mother, which included a particular care for those at sea. Financial difficulties delayed his attempts to enter the Church, but, in 1834, he married and secured a place at Oxford. At this moment, the established Church not only faced internal calls for reform, but felt outwardly beset by the rise of non-conformity, irreligion in Britain’s burgeoning industrial cities and Catholic emancipation. Indeed, as Woodard began his university studies, the Oxford Movement, which would carry a cohort of celebrated clergy — and some of his friends — over to Rome, was already under way.

Woodard did not follow, but his High Church or Tractarian sympathies shaped his early career. In 1843, as curate of St Bartholomew’s, in London’s Bethnal Green, he preached a sermon in which his ideas about confession prompted a complaint. He was forced to resign and, after another unhappy period in a neighbouring parish, he secured a living at Shoreham, West Sussex, an ancient port town that had fallen into modest Victorian prosperity. The 35-year-old curate was shocked by the dislocation between the town and the church, as well as by the lack of any formal provision for the education of its professional class. Accordingly, on January 11, 1847, he opened a small day school in the vicarage, with a curriculum that included such subjects as navigation and bookkeeping.

Woodard’s time in London had given him some important connections and also, perhaps, confidence as a campaigner. Certainly, he pursued causes with an absolute determination and phenomenal success, aided by charm, humour and an earnest sense of high purpose. In March the following year, he published a pamphlet entitled A Plea for the Middle Classes, suggesting that their educational needs were overlooked. He proposed that there should be modestly priced schools for boys respectively from the upper, middling and lower degrees of this class. It was on their Christian education, he argued, that the ‘political and moral well-being of the nation’, as well as its future prosperity, depended.

His cause found support among such influential figures as William Gladstone and the Marquess of Salisbury. As money also came to hand, his practical response to the problem set out in the pamphlet began to evolve very rapidly. On August 1, 1848, Woodard became founder of another new school in the town. St Nicolas’s Grammar School and Collegiate Institution, as it became known, took its dedication from Old Shoreham parish church. It was intended for boarders and aimed to attract boys from upper-middle-class families, the sons of gentry, clergy and professionals. Another local foundation, St John’s Middle Grammar School, the future Hurstpierpoint College, was established in the town the following year for those of middling degree within the middle class, the sons of clerks and tradespeople.

In the meantime, Woodard turned to one of his London friends, an almost exact contemporary, Richard Cromwell Carpenter, to create buildings for his new foundations. Carpenter, a friend of A. W. N. Pugin, was already well established as a Tractarian church architect. He drew up grandly conceived plans for both institutions. In each case, these were cast in an English medieval style around courtyards. The foundation stone of Carpenter’s Hurstpierpoint was laid on June 21, 1853, but, before work began to St Nicolas’s, Woodard’s plans for the college had changed completely.

The ink of Carpenter’s drawings can hardly have been dry before Woodard purchased Burwells and Malthouse Farms in 1852. These stood in the neighbouring parish of Lancing and the attached land offered a dramatic new building site perched high in the South Downs. Woodard clearly saw the potential of the site for a spectacular architectural gesture delivered by a chapel of stupendous size (Fig 1). The story is told that Carpenter was unhappy with the proposed site and the problems it presented. Woodard replied: ‘I did not ask you if you could build a chapel there; I told you to build it. If you will not build it, I will find an architect who will.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Carpenter was compelled to reconfigure and further enlarge his collegiate plan for this new site, but by this time his health, which had always been delicate, was failing. A foundation stone for the college buildings was laid in the lower quadrangle on March 21, 1854, and, almost exactly a year later, the architect was dead. A perspective view of his proposed design was published posthumously with an obituary in The Ecclesiologist, late in 1855. The one omission, however, was the chapel, which was shown only as a footprint projecting out from the main complex eastwards across a steeply falling hillside (Fig 3). As the obituary also noted, responsibility for the work passed to William Slater, Carpenter’s ‘earliest pupil and friend of 20 years’.

Within a year, visualisations of the chapel, attributed to Carpenter and Slater and closely resembling later designs, were published. Nothing, however, was immediately begun. Rather, the first concern was to complete the main school buildings. Meanwhile, such was the success of Woodard’s pamphlets, letters and campaigning that, during the 1860s, the college began to emerge as the senior and focal institution of a national network of schools. It was to reflect this flagship role that, despite so many wider demands, Woodard planned a grand foundation stone-laying ceremony for the new chapel at Lancing on July 28, 1868.

Slater was still the architect, but acting in partnership with Carpenter’s son, Richard Herbert Carpenter, and the foundation-stone inscription explicitly identifies them both as ‘masters of the work’. An article in The Builder the following month described the new chapel as it was planned: a vast aisled structure 170ft long, vaulted throughout and divided into a choir and antechapel, respectively of nine and three bays. The former was to accommodate 450 people and the latter (together with the aisles) to provide extra space on special occasions, such as an annual gathering of all Woodard’s schools. Each of the aisles and the main vessel was to terminate in an apse, the former projecting from a pair of towers with spires that flanked the choir and with altars dedicated to the Virgin and St Nicolas. The high altar was to be raised on a dais within the main vessel of the interior and there was to be a western rose window.

At the south-west corner of the building, a huge belfry tower 350ft high was planned. It was to incorporate the entrance porch, but the whole was to be ‘one of the most prominent objects on the south coast’ and to be fitted up as a lighthouse. Woodard wished it to contain a chapel to be used for intercessory prayers during storms and hoped that it would be funded and built by the women of England. To accommodate the fall of the hillside, the chapel was to be built over a large crypt and the south side of the building was to be lined with a cloister walk.

A plan and eastern elevation were published on December 26, 1868, when the cost was estimated at £300,000. The prescient prediction was made that the building would ‘probably be a long time in construction’. Massive foundations were sunk up to a depth of 70ft and a sandstone quarry was bought at nearby Scaynes Hill to supply the work.

Slater died in 1872 and, by the time the crypt was consecrated on October 26, 1875, the whole project had passed into the hands of the younger Carpenter, who seems to have further refined the chapel design in 1877. The crypt is inspired by that of Canterbury Cathedral in Kent (Fig 6), but the overall design of the chapel was eclectic, drawing on different national traditions of Gothic. In plan, there are evocations of German design, but the high roofline, soaring interior, window tracery and internal proportions breathe the spirit of French High Gothic cathedrals (Fig 2). There are also, however, complex mouldings characteristic of English buildings and some specific quotations from Westminster Abbey, notably the use of white clunch to create bands of colour in the high vault.

In 1882, Woodard gave the instruction that the east end of the chapel should be raised up to its full height in order that ‘should a niggardly generation arise and decide that it is too costly to build to the height I desire, then my work will have to be pulled down’. Instead, work continued steadily through Woodard’s death in 1891 — he was buried in the shadow of the chapel — and that of Carpenter two years later. He was eventually succeeded as architect by Temple Lushington Moore, but the real figure in the interim, and who drove forward the project until his death in 1918, was Woodard’s son, William. Despite a shortage of funds, he turned all the vaults and oversaw the completion of all but two bays of the main interior, which was consecrated and taken into use on July 18, 1911.

One practical reason for the truncation of the antechapel was that the intended link with the school buildings had been overbuilt with a kitchen. Other changes and economies had also overtaken the 1868 designs. These included the loss of the eastern apsidal chapels of St Mary and Nicholas and, in 1877, the movement of the great belfry from the south to the north of the west end. Work to this last structure never progressed beyond the foundations. From 1921, Moore adapted the design of the chapel cloister, turning it into a war memorial. He also designed the two chantry chapels flanking the choir steps, one to Woodard and the other to his son (Fig 7). The latter is a re-creation of the Ogle Chantry at Hexham in Northumberland.

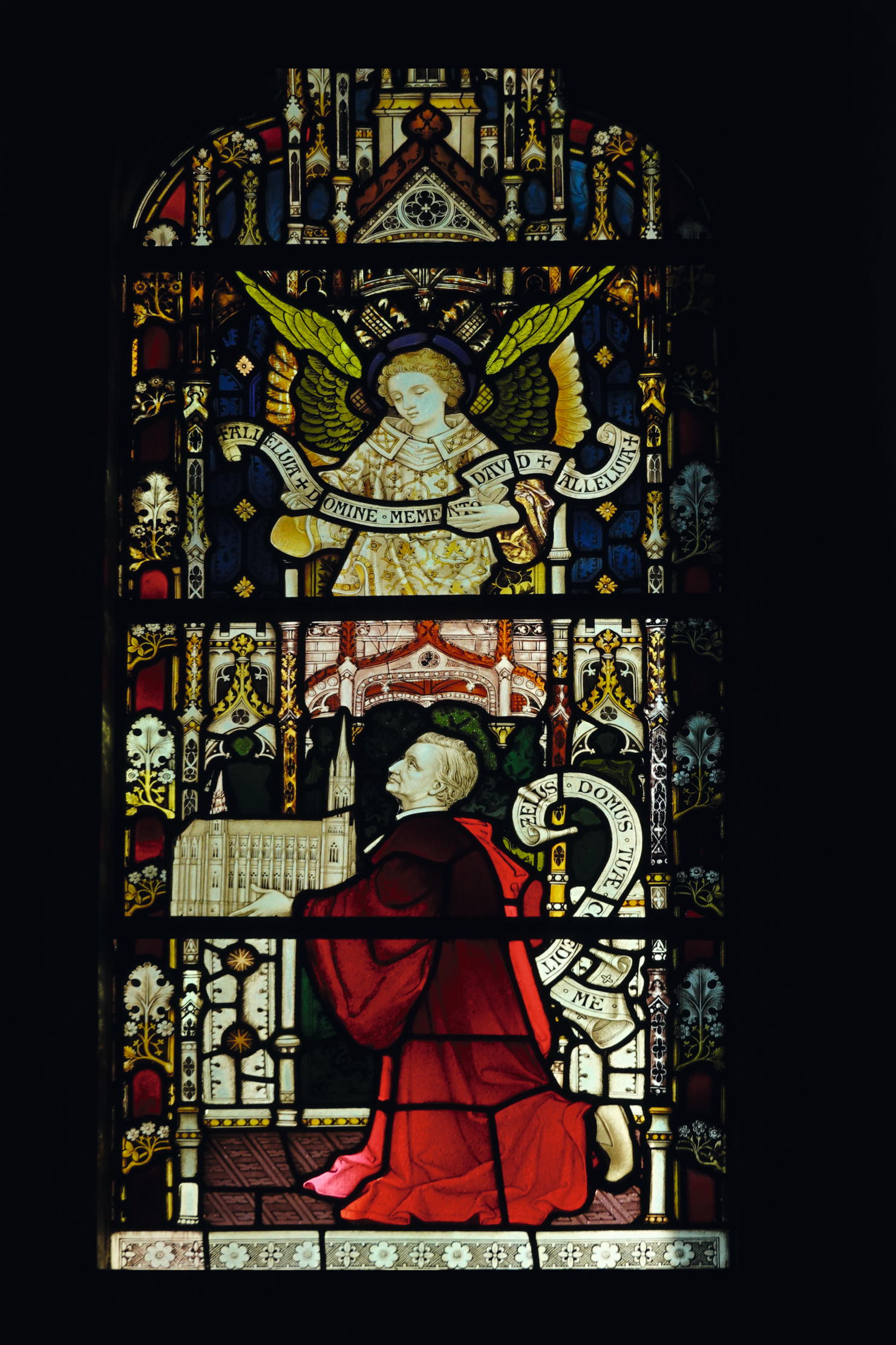

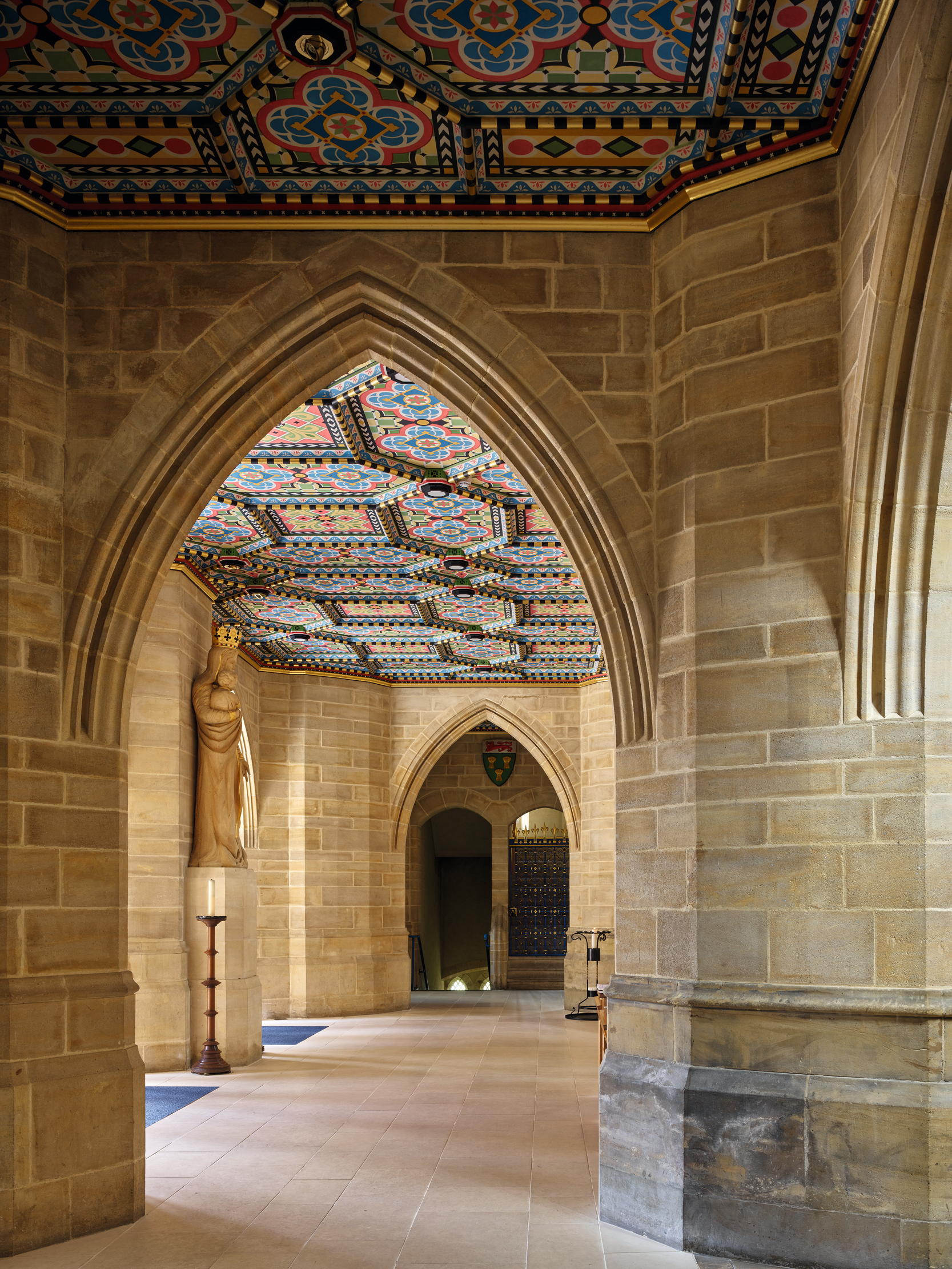

For the next 60 years, the truncated west end of the chapel was closed with a wall of timber and corrugated iron. Efforts to complete the building were initially unsuccessful and, in the meantime, the interior was furnished with stalls incorporating canopies from Eton College Chapel, Berkshire, in 1923 and — in a fortunate exchange — a series of three tapestries designed by Lady Chilston, instead of a stone high altar reredos in 1933. It was not until the 1970s, with help from the Friends of Lancing Chapel, a group that was established in 1946, that the funds became available for the architect Stephen Dykes Bower both to cap the eastern towers with low roofs (rather than spires) and to begin a narthex (Fig 8) and gable wall set with a great rose window. This is decorated with the arms of the other Woodard schools, an impressive splash of colour in an interior otherwise flooded by sunlight through huge expanses of clear glass (Fig 5).

After a consecration ceremony attended by the then Prince of Wales on May 13, 1978, however, the project languished and the vaulted antechapel Dykes Bower additionally intended to create beyond it was left unfinished. Efforts to complete the building continued under his successor and pupil, Alan Rome, who also undertook extensive restoration work to the external masonry.

It was not until 2019, however, that permission was granted for Michael Drury’s western porch, inspired by that of Snettisham Church, Norfolk (Fig 4). Work also included replacing brickwork in the facade and the completion of buttresses. The pandemic almost derailed the £1.25 million project, but the chapel now stands complete and is an impressive complement to the college buildings, which we will examine in a separate article.

Acknowledgements: Jeremy Tomlinson and Peter Birts.

Country Life Today: Britain's longest-running building project is about to come to an end

After more than a century and a half, Lancing College is set to finish its chapel, while we also look

The worst garden pests of all? The ones you invite in with open arms

A couple of weeks ago, Alan Titchmarsh wrote a lovely piece for Country Life about how to get children and

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published