The oldest house in Britain — and how we were able to tell it apart from the other contenders

There are many nominations for the oldest home in Britain — in this piece from the Country Life archive, John Goodall gives as close to a definitive answer as we may ever get.

Every Tuesday, we look back at an article from Country Life's peerless architecture archive. This week, we unearth John Goodall's piece from August 28, 2003, naming Britain's oldest continually-occupied house after a campaign that ran over the summer of that year.

Country Life’s search for Britain's oldest continuously inhabited house has been a revelation to me, introducing me to a surprising range of little-known houses in a field of architecture with which I believe myself to be familiar. It has also vividly reminded me of a circumstance so obvious that I always tend to forget it: that masked behind the trappings of the 21st century, the distant past is physically woven into the fabric of British life.

In trying to arbitrate on a subject of this kind, definition is everything. The terms of the search as laid down in the editorial last month cut out certain categories of building, and it is worth explaining why.

First, Britain's principal royal palaces have not been considered. This is largely an acknowledgement of their peculiar status, but also because they would eclipse competition. Westminster Palace, for example, is physical testimony to nearly a thousand years of architectural and institutional development.

Although nothing may survive of Edward the Confessor's original palace — and, incredibly, the last vestiges of this may have been destroyed only in the 19th century — the Great Hall is an extraordinary survival that brooks no parallel. Reworked in both the 14th and 19th centuries, the walls of this vast building are substantially those completed by William Rufus in 1099.

Churches and monastic buildings converted to domestic use have also been excluded. We are looking for ancient houses, not houses that happen to incorporate ancient remains. But certain ecclesiastical residences, including those of abbots, priors, and canons have been allowed. Whether or not these have passed out of ecclesiastical use they are truly houses and must be acknowledged as such.

The principal qualification is that the house in question should preserve physical evidence of its great age. In Britain it is relatively common for long continuity of occupation to be reflected in street plans or settlement patterns. Such antiquity is both remarkable and important, but it cannot be meaningfully quantified.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

If physical remains exist they must be incorporated within the house that claims descent from them. So, for example, the existence of ruins, a castle wall, or even of a roofed but redundant house, do not count as adding to the considered age of an adjacent and functioning residence. On these grounds, the celebrated late-12th century chamber block at Boothby Pagnell, Lincolnshire, or the roughly contemporary Sinnington and Burton Agnes in Yorkshire must be excluded.

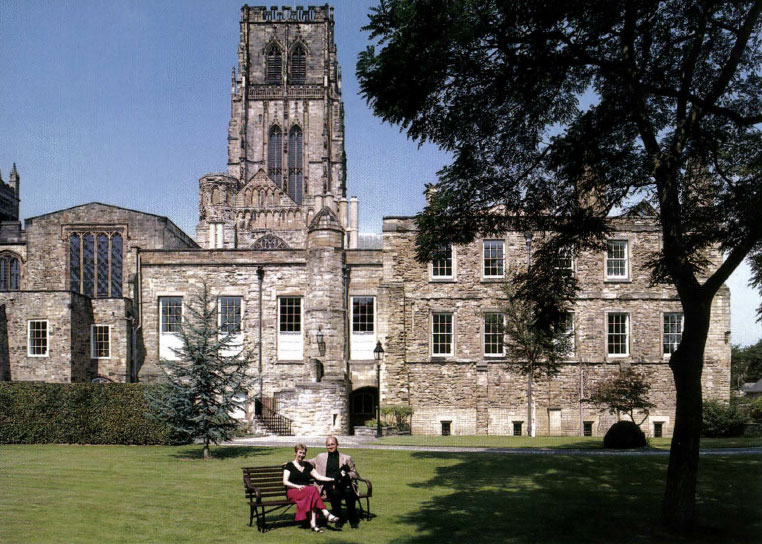

There are two further buildings which I have reluctantly disqualified. In the mid-13th century, the Prior of Durham massively expanded his house as part of the reordering of the monastery and absorbed within it a section of the old monks' dormitory, first laid out in about 1075- 80. The Prior's House has served since the Reformation as the Deanery (Fig 4) and, so in a sense, these buildings have had a truly domestic function for more than nine centuries. But they have not always been a house.

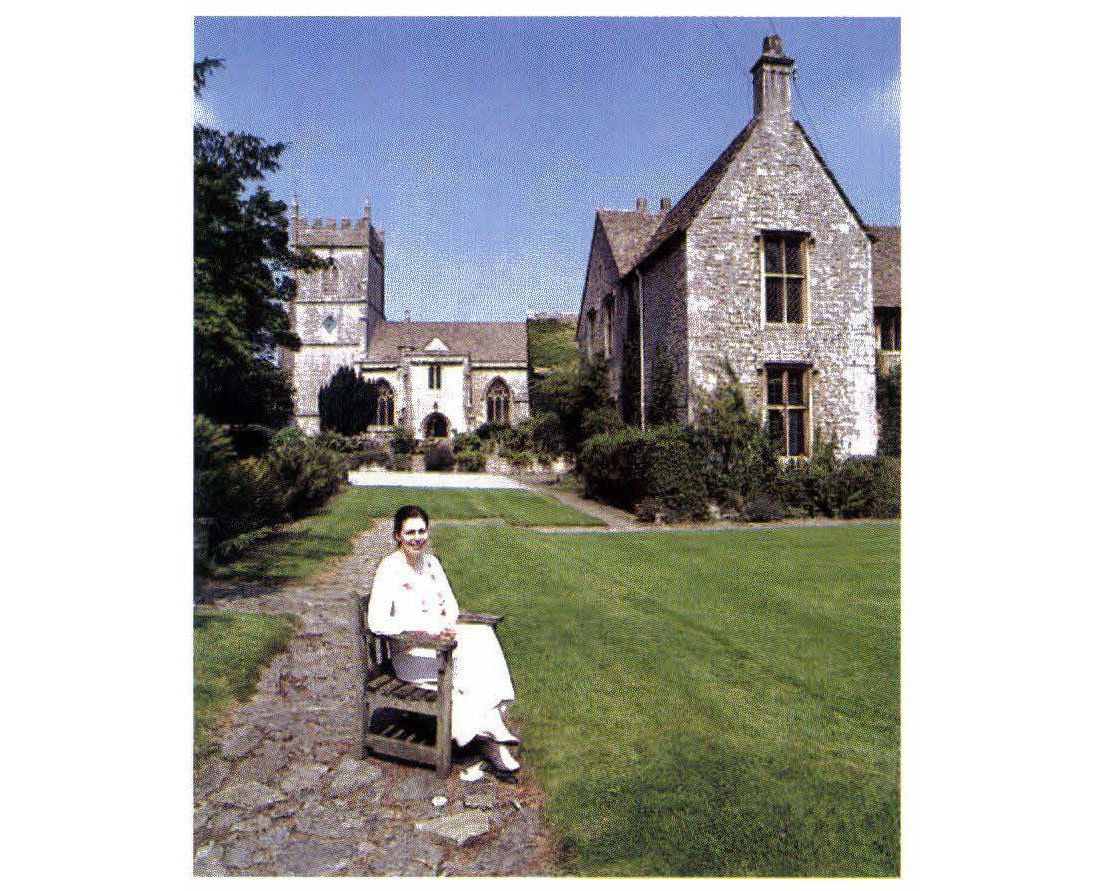

Similarly, Berkeley Castle (Fig 2) does not properly qualify as a house but has remained in occupation for a similar period of time. It was founded soon after 1067 by William FitzOsbern and may have been briefly abandoned after 1088.

Whatever the case, William probably raised the castle motte, which was reworked in the 1150s during the construction of the present keep. Since that time, the Berkeley family has continued to occupy the castle without intermission and have further developed it architecturally.

Having established the qualifications for any house in the running it is worth taking at random a benchmark building to set the field in perspective. Cranborne Manor in Dorset is a 17th-century house which contains the remains of a hunting lodge built by King John in 1207- 8. So nothing built after about 1200 is seriously in competition for the prize.

The vast majority of readers' nominations fell after this date, with numerous suggestions in the 13th and even the 14th centuries. A threshold of 1200 also appears to exclude any Scottish, Welsh or Irish building.

It is rarely possible over a period of 800 years satisfactorily to demonstrate the continuous occupation of a house. Indeed, the meaning of occupation could be differently construed in different periods. In the Middle Ages, for example, a great nobleman might own residences which, by reason of his peripatetic lifestyle and the quantity of his property, he might rarely — or never — visit. For present purposes, therefore, I have assumed that a building can be deemed to have been continuously occupied if it has never fallen totally into ruin.

I have, however, made one exception to this rule. Whether roofed or not, the abolition of the episcopacy during the Commonwealth technically removes all bishops' houses from the running. This means excluding two very remarkable survivals: the 12th-century great halls at Hereford (about 1179) and Bishop Auckland, Co Durham, both of which still serve as episcopal residences.

This ruling also clarifies an important ambiguity. Many post-Restoration bishop's palaces have incorporated fragments of old ones and in most cases — such as Wolvesey Palace at Winchester — it seems distorting to view the two as the same house.

Two other great bishop's residences, which might be otherwise discounted, also deserve particular mention for their outstanding early remains: Farnham Castle, Surrey, which has a 12th-century great hall, and the great castle of Durham, with surviving fabric dating hard upon its foundation in 1072.

Besides escaping ruin, all contenders must at present be lived in as houses, not merely occupied by an institution or shop. Again, this requirement removes some important survivals from the field. In order of approximate age these are: Merton Hall, Cambridge (about 1200); the Old Deanery, Gloucester (about 1200); Gray's Court, York (late 12th century); Moyse Hall on Cornhill Street in Bury St Edmunds (about 1180); the Jew's House and the Norman House at Lincoln (1170-80); 65 and 67 High Street, West Malling (1160- 80); 28-30 King Street, King's Lynn (1150-73); 11 St Mary's Hill, Stamford (which incorporates a doorway of about 1150); Wensum Lodge on King Street in Norwich (early 12th century); and Nyetimber Barton, Pagham in Sussex (possibly with 11th-century masonry).

As a special sub-category within this group are buildings that continue to serve an inherited medieval judicial function. Most important of these are the 11th-century foundations of Oxford Castle (founded in 1071) and Lancaster Castle, both with important early medieval structures virtually unknown by reason of their continued service as gaols. It is hoped that this situation will change soon in the former case, now that the prison has closed.

Similarly, the 1190s great hall of Oakham Castle served until very recently as a court house. The great hall of about 1150- 60 at Leicester Castle is still in use as such.

We are now coming to the list of finalists, but before engaging with them it is important to come clean about a central problem that has been glossed over. Dating buildings accurately in the 12th century is a complicated and often subjective task. Generally speaking, there is little documentary evidence to rely upon.

Moreover, domestic buildings tend to be poor in the decorative architectural detailing that scholars conventionally rely upon as indicators of elate. In recent years, however, the so-called dendrochronological dating of timbers has revolutionised our understanding of many early buildings. Visible on the cross-section of any tree-stump is a pattern of concentric rings.

Each ring corresponds to one year's growth and a group of them can be used to date a tree precisely. Because the weather in different years makes trees grow to a different extent — fast or slowly — the rings are not evenly spaced. And cumulatively the variations in growth create distinctive patterns.

Such patterns can be matched against a master sequence of tree rings and precisely located within it. By taking bored samples of timber from buildings, therefore, it is possible to date timbers by the patterns of rings within them. The most useful samples for this purpose culminate in bark, the outermost tree ring at the time of felling. Medieval carpenters usually worked timbers when they were green, so the felling date can be assumed to approximate to the construction date.

More typically, however, the bark is missing from samples and the felling elate must be calculated working from the date of the last surviving ring. The discoveries effected by this technique in recent years have been remarkable: just two years ago, for example, the timbers of an old door in Rochester Cathedral turned out to have a felling date of 1066. Fyfield Hall, Essex, which was nominated by several readers, has been dated by this method to the late 12th century, the mean felling year of its timbers calculated as about 1178. As yet, this is the earliest inhabited domestic timber-framed structure known to exist in Britain.

Fyfield eliminates a group of buildings roughly dating from the last quarter of the 12th century, such as Appleton Manor, Berkshire; Manor Farm, Hambledon, Hampshire; the Knights' Templar Hall, Temple Balsall, Warwickshire; Newbury Farmhouse, Tonge, Kent; Irnham, Lincolnshire; Deloraine Court, Lincoln; and Bury Court, Redmarley D'Abitot, Gloucestershire.

But to accept Fyfield as Britain's earliest inhabited structure would be to ignore a small field of mid-12th-century stone domestic structures which are probably earlier. Unfortunately, it is virtually impossible to sort these accurately by date. Indeed, one house — Red House, Little Dean, Gloucestershire — must be ruled out as being undatable.

Of the three remaining I would tentatively suggest that Horton Court, Gloucestershire and Hemingford Grey, Cambridgeshire, date respectively to the 1160s and 1150s.

If this is correct, then the oldest continuously occupied home in Britain is Saltford Manor House, Somerset, with fabric plausibly datable on stylistic grounds, and for certain points of similarity with Hereford Cathedral (complete by 1148), before 1150.

Credit: Will Pryce/©Country Life Picture Library

The Chapel of Trinity College, Oxford: A return to splendour

One of Oxford’s most admired interiors has been revived, as John Goodall reports.

Orthopaedic shoe-making: The bridge between architecture and podiatry

John Goodall meets Bill Bird, who, having studied architecture at the Bartlett, now makes orthopaedic shoes.

The Country House Library: Why these rooms and their collections need to be taken much more seriously

A new account of the country-house library will compel us all to reassess these rooms and their collections, says John

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes