Norfolk House: The lost London palace that was razed to the ground, recreated 80 years on

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the sale and demolition of Norfolk House. John Martin Robinson re-creates the splendours of this outstanding Georgian town house with the help of historical photography and a reconstruction drawing specially commissioned by Country Life.

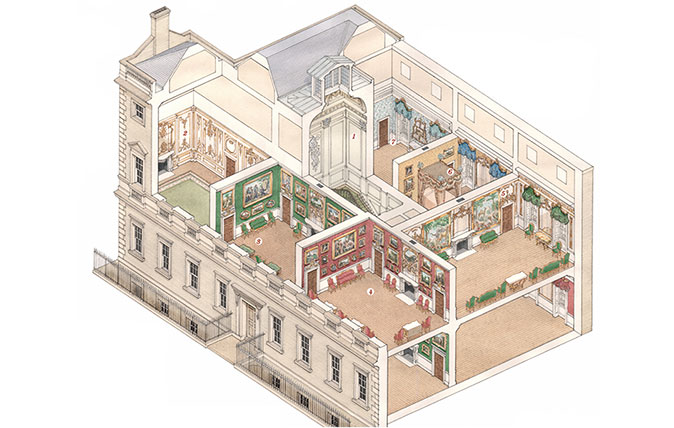

Plans, inventories and old photographs offer sufficient information to reconstruct the piano nobile and even its picture hang as it appeared at the opening party in 1756, when it was described by Horace Walpole as a ‘scene of magnificence and taste’. This cutaway, specially commissioned by Country Life, shows the continuous enfilade of magnificently decorated rooms set around the principal staircase (1): Music Room (2), Green Drawing Room (3), Crimson Velvet Drawing Room (4), the Great or Tapestry Room (5), State Bedroom (6) and State Dressing Room (7). Not visible here are the anteroom and China Closet that respectively opened and closed the sequence of rooms. Illustration by Stephen Conlin, ©Country Life Picture Library.

Norfolk House on St James’s Square in London SW1, built between 1748 and 1752, was one of the finest examples of mid-Georgian architecture in London, the town house of eight successive Dukes of Norfolk and a magnificent centre of social life and aristocratic entertainment. It also served as the Earl Marshal’s office for the Coronations of Edward VII, George V and George VI.

Under the 14th and 15th Dukes of Norfolk in the second half of the 19th century, it was the centre of lay Catholic life in England, playing host to the Catholic Union of Great Britain, the Catholic Record Society, the Catholic Poor School Committee and many charities, as well as being the setting for a three-day reception for Cardinal Newman in 1879. It seems incredible that it could have been demolished only 80 years ago.

In fact, this was the last of the private palaces to go during the great early-20th-century clearance of major aristocratic houses in the West End. As well as the economic reasons, such as falling rents, agricultural depression, shortage of staff and high taxes, that threatened country houses, town houses were also vulnerable to commercial redevelopment pressures, as their spacious freehold sites were extremely valuable and suited to speculative blocks of flats and offices.

Before the Second World War and the system of listing buildings, there was little practical protection and certainly no will for preserving historic houses (just as is the case with the ruined historic London skyline today).

Moreover, large aristocratic houses increasingly became superfluous after levées or Morning Courts at St James’s Palace – which had required peers, ministers, diplomats and all men of influence (including senior Anglican bishops) to maintain places in the capital – were gradually discontinued. Thereafter, a flat or a small house in Chelsea was cheaper and more convenient for modern metropolitan life.

In Paris, Rome or Vienna, the greatest town palaces became embassies, clubs and cultural institutions in the 20th century. This did not happen much in London, although it could have (indeed, many of the demolitions seem, in retrospect, unnecessary and avoidable). In an heroic precedent, Lord Leverhulme (Country Life, May 23, 2018) bought Lancaster (Stafford) House for the nation as early as 1913 and, after the First World War, he nearly saved Grosvenor House for use as a sculpture museum (his executors reneged on the deal). The Italians almost managed to secure Dorchester House as their embassy, for which it was eminently suited architecturally.

One by one, the big London houses were sold and the wrecker’s ball assumed a dreadful inevitability. Devonshire House, which had been used as a hospital in the First World War, was one of the first to go, being given up in 1919 and demolished in 1924 to make way for a block of flats by the American architects Carrère & Hastings (Country Life, August 25, 2010).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was followed by the Duke of Buccleuch’s Montagu House in Whitehall for Government offices in 1925, the Duke of Westminster’s Grosvenor House in Park Lane in 1927 and the Holfords’ Dorchester House in 1929, both for hotels. Chesterfield House, latterly the town house of the Earl of Harewood and the Princess Royal, went in 1937, making way for particularly unsightly flats and, in 1938, Lansdowne House was mutilated by London County Council for road ‘improvements’ and the remnants converted to a club. Finally, Norfolk House was demolished and replaced with offices in 1939.

The house had first been offered for sale in 1930, when the particulars by Hamptons described it, optimistically, as suitable for a ‘nobleman’s residence’, embassy, club or institutional headquarters (one hope was that it might become a club for the Automobile Association, to match the nearby RAC in Pall Mall). It failed to reach its reserve, however, and continued in use, serving as the Earl Marshal’s office for the 1937 Coronation.

Gwendolen, the dowager Duchess of Norfolk, was opposed to its sale or demolition and, as it was included with other property in her marriage settlement, she had the right of veto until her son, Bernard, 16th Duke, married Lavinia Strutt in 1937.

Thereafter, the trustees had the unfettered right to sell. When signing away her interest, the dowager duchess wrote ‘with protest’ on the legal document and became a founder member of the Georgian Group in reaction. Country Life photographed and wrote up the house on December 25, 1937.

The freehold was acquired by a developer, Rudolph Palumbo, in 1938. He built a dull neo-Georgian block designed by Gunton & Gunton on the site, which served as Eisenhower’s London headquarters during the Second World War. If the house had survived another year, it would have been listed and preserved after 1945. Bernard Norfolk later said he regretted its loss, but he was young at the time and, faced with death duties, bequests and debts, he deferred to his elderly trustees.

The Norfolk presence in St James’s Square dated back to 1722, when the trustees of the 8th Duke bought St Alban’s House for £10,000. The house included a frontage to the square at the heart of a fashionable new aristocratic quarter that adjoined St James’s Palace and stretched back for 200ft, with coach houses and subsidiary buildings in Charles Street. When the 8th Duke’s younger brother Edward (Ned) inherited in 1732, the latter had ambitious plans for the site. He and his powerful, cultivated, energetic wife, Mary (Blount) set out to make the house a metropolitan demonstration of their loyalty as Catholics to the Crown and their rank as premier peers.

A Jacobite when a young man, Ned had been taken in arms at Preston in 1715 and tried for treason. His life was saved by his elder brother pledging support in person to George I. In case there were lingering doubts, Ned wished to show publicly that he was a loyal subject of the Hanoverians and supporter of the Whigs.

In 1737, he lent the old house to Frederick, Prince of Wales, and the future George III was born there. Subsequently, the 9th Duke set about rebuilding the place on a palatial scale.

He was able to buy Belasyse House to the north in 1738, and combined the two freeholds to create a frontage of 109ft. Both houses were demolished and replaced with a single, three-storey structure designed by Matthew Brettingham Sr between 1748 and 1752. The exterior was faced in fine ‘white brick’ from Norfolk with Portland dressings. Altogether, it was a dignified Palladian composition with good proportions – the only decoration was restricted to alternating segmental and triangular pediments to the first-floor windows. The plan was derived from the family wing at Holkham, with continuous circuits of rooms on two floors arranged around a central full-height staircase hall lit by a roof lantern above.

The family rooms were on the ground floor, with two drawing rooms, the dining room and the duke’s bedroom and dressing room. The glory of the house was the piano nobile, with a continuous enfilade of magnificently decorated and furnished entertaining rooms: ante room, Music Room, Green Drawing Room, Crimson Velvet Drawing Room, the Great or Tapestry Room – later the Ballroom – State Bedroom, State Dressing Room and China Closet. Illustrating this article is a series of previously unpublished photographs of these rooms that were taken in the 1870s by Bedford Lemere, possibly following the marriage of the 15th Duke.

There is often a contrast in English Classical houses between reticent exteriors and rich, Franco-Italian interiors, a convention started by Inigo Jones at the Queen’s House and Wilton. At Norfolk House, the contrast was extreme and reflected the Norfolks’ position: dignified plain English to the outside world and full-blown uninhibited Continental Catholicism within, including a two-storey private chapel at the back, which opened off the duke’s apartment, with tall arched windows, polished mahogany pews and a Baroque altarpiece painting of the Crucifixion. The chaplain had a domain on the second floor, with a bedroom and library, as was also the arrangement at Arundel.

The contrast was architectural as well as psychological and was part due to a change of designer. Decent but dull Brettingham was let go. The interior fitting was the work of Giovanni Battista Borra (1713–70) under the personal direction of the duchess, who herself took a strong personal interest, choosing colours and ornaments and buying Gobelins Nouvelle Teinture des Indes tapestry, seat furniture by Nadal l’Ainé and mirror glass directly from Paris, where she was received at Versailles by Louis XV.

Borra was a Piedmontese architect and a pupil of the Baroque master Bernardo Vittone. He had been draughtsman to Wood and Dawkins on their tour to Baalbec and Palmyra. His drawings of those temples, together with his memories of north-Italian Baroque, created an original and dynamic Classical Rococo synthesis.

In England, Borra worked largely in the circle of the Prince of Wales, designing the State Bedroom at Stowe for the Grenvilles and interiors at Stratfield Saye for the Pitts, but Norfolk House was his magnum opus and his interaction with the Francophile duchess (who collected French engravings by Blondel and Meissonnier as a source), led him to develop fully his Italo-Rococo style, especially in the staircase hall, Music Room and drawing rooms, which proved the prototypes for his future work at Racconigi and other Savoy palaces after his return to Piedmont in 1756.

Borra designed all the chimneypieces, mirror frames and pier tables. The latter are now at Arundel, where some of the best furniture, portraits and muniments were taken in 1938. The residual contents, including a group of seicento paintings imported specially from Leghorn for the two drawing rooms, were sold by Christie’s. The interior fittings were salvaged and recycled, especially the Music Room, which was given to the V&A and the state-bed curtains miraculously survive at Ugbrooke Park.

Thomas Clarke, who had worked at Holkham, was responsible for stucco and Joseph Metcalfe for seat furniture. Canaletto, when in London, was commissioned for three overdoor paintings of architectural capriccio for the ground-floor Green Drawing Room. Recent research has shown that this team was also involved in the lost contemporary interiors at Northumberland and Chesterfield Houses, important monuments of English Rococo patronage.

The interior of Norfolk House largely survived in its original form throughout its existence. Some contents were sent to Worksop to furnish the new manor house there after a fire in 1761. Robert Abraham, a pupil of Nash, added an Ionic portico and created a new dining room in the early 19th century, and successive Victorian dukes employed the firms of George Morant and then Charles Nosotti for regular redecoration, gilding and titivation.

Nevertheless, the rooms remained largely as created by the duchess and Borra to the end. It is a small tragedy that it is only possible to evoke them today through historic photographs and this drawing.

The Dukeries: Is this Nottinghamshire's best kept secret?

Get your dukes in a row.

Fawley Court: A house by the Thames bearing the fingerprints of Wren and Wyatt

Two of Britain’s greatest-ever architects, Christopher Wren and James Wyatt, have been linked with the creation of Fawley Court.

Who Designed Houghton? by John Harris

From the Country Life Archive: Could it be that Houghton Hall in Norfolk was not designed by Colen Campbell, but

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Love, sex and death: Our near-universal obsession with the rose

Love, sex and death: Our near-universal obsession with the roseNo flower is more entwined with myth, religion, politics and the human form than the humble rose — and now there's a new coffee table book celebrating them in all of their glory.

By Amy de la Haye Published

-

The sounds of spring and stained glass in an Arts-and-Crafts masterpiece in Dorset

The sounds of spring and stained glass in an Arts-and-Crafts masterpiece in DorsetWith 35 acres, more than 10 bedrooms, a swimming pool and tennis court, Winterfield has it all.

By James Fisher Published