Munstead Wood: The house that Edwin Lutyens built for Gertrude Jekyll

The creation of Munstead Wood in Surrey came from a happy friendship between a great gardener and architect, both closely connected to Country Life. Clive Aslet explains.

One summer’s day in 1889, the 20-year-old Edwin Lutyens went to a tea party in the Surrey hills, near the village where he had grown up. At this party, he met the gardener Gertrude Jekyll, a lady who was more than 20 years his senior, well connected and a skilful craftswoman. Conversation between them did not flow, but, as she was on the point of stepping onto her pony cart, she asked him to call on her the next day at Munstead House, outside Godalming. It was the beginning of an exceptional friendship. With her strong ideas about homes, she shaped the young man as an architect — not least by entrusting him with the design of her own home of Munstead Wood.

Impishly, Lutyens caricatured Jekyll in his letters to his wife, Lady Emily, as a stout if commanding figure, in, as he remembered, ‘a black felt hat turned down in front and up behind’. Photographs show that his sketches were not far from the truth, but Jekyll had not always been 45; as a young woman, she had been an elegant equestrienne, as well as an adventurous traveller — although friends regarded her, even then, as indomitable: a sketch from the island of Rhodes shows her in ‘heavy marching order’, weighed down by drawing impedimenta. Her parent’s circle had been intellectual and artistic.

The young Gertrude read Ruskin, whom she later met, and attended the Kensington School of Art. A portrait of her at 33 was written by George Leslie, RA: ‘Clever and witty in conversation, active and energetic in mind and body… there is hardly any useful handicraft the mysteries of which she has not mastered — carving, modelling, housepainting, carpentry, smith’s work, repoussé work, gilding, wood-inlaying, embroidery, gardening and all manner of herb and culture.’ Gardening took centre stage when poor eyesight made fine work, such as embroidery, more difficult.

Unlike the watercolourist Sir Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, or ‘Brabby’ as Jekyll called him, she was not a gentleman amateur who did not need to sell work. Rather, she was an unmarried woman without a great inheritance who had to make her talents pay. Munstead Wood was, therefore, not only the place she lived, amid carefully curated surroundings, but also her place of business. The house contains a room for the practice of craft, stored with woods for inlay, sheets of horn, bone and tortoiseshell, as well as examples of her work (Fig 5) and no doubt her carving (Fig 6). There is also a collection of ornamental hinges, keys and handles; a book room where she wrote books and articles; a dark room where she developed the photographs she took, often to be published; and a shop where flowers could be sold to the public.

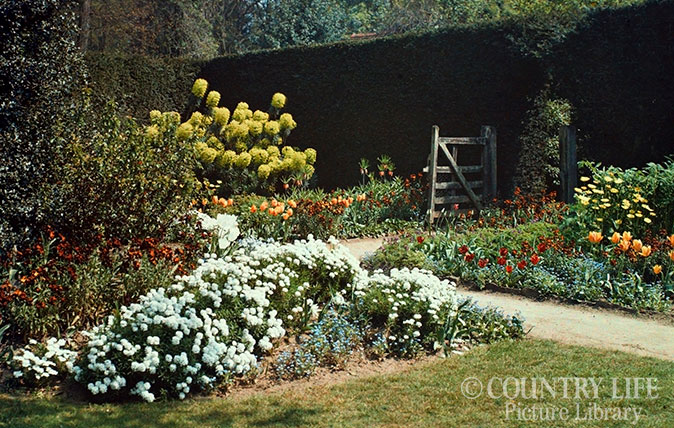

As well as designing gardens, she supplied the plants for them from her own nursery and her own garden provided a constant supply of subjects to photograph and write about. The house was but one incident in Jekyll’s busy domestic world, much of which was spent outside, wearing the famous boots — now at Godalming Museum — that were painted by William Nicholson. Work on the garden began years before that on the house.

Both Jekyll and Lutyens, although born in London, had spent a good part of their youths in Surrey. Childhood illness meant that Lutyens did not go to boarding school, like his brothers, but stayed at home, exploring the Surrey lanes. Jekyll’s parents had moved to the county when she was five. For a time, they transferred to Berkshire — a period of exile, as Gertrude saw it — but, after Capt Jekyll’s death, his widow and Gertrude settled at Munstead House, built for them by the Aesthetic Revival architect J. J. Stevenson. Gertrude’s travels were now over; thereafter, she rarely went beyond a narrow radius of Godalming.

The railway had come to Surrey and artists such as Jekyll’s friend Helen Allingham had discovered it, too. Earlier in the 19th century, William Cobbett had loathed the unproductive heaths, but the backward agriculture continued to support (in the words of Jekyll’s Farnham contemporary George Bourne) ‘the home-made civilization of the rural English’. In Old West Surrey, 1906, Jekyll mourned the disappearance of the handmade sugar-nippers, wicker birdcages, smocks and horse accoutrements, which, as they went out of use, she collected. For her, the heathy soil of Munstead Wood was not barren, but ideal for the sort of plants she had seen on her travels around the Near East. She mixed native plants with exotics, grew clematis and roses through the silver birches of the woodland and planted the scars left by old tracks with spring bulbs.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Lutyens had already opened his first office when he met Jekyll: he did so at the age of 19, with only the barest of training. Indeed, he had received little formal education of any kind, having been denied school due to rheumatic fever. If self reliant, he suffered from shyness, hidden behind a quick-fire and often hilarious succession of jokes, puns and doodles. To date, his few buildings do not readily show the promise that Jekyll clearly saw in him. She had strong views, but not the skill to realise them in three dimensions, so needed an architect and set about giving Lutyens an education in the Arts-and-Crafts style.

Together, this oddly assorted couple explored local villages, exclaiming delightedly on the buildings. The modest nature of the first dwelling that Lutyens designed for her is signified by its title, The Hut. This was an almost genuinely cottage-like structure — ‘tiny,’ as Jekyll described it in Home and Garden (1900) — designed after the death of Jekyll’s mother in 1895 made her vacate Munstead House, which was then occupied by her brother and his family. It is a composition of low eaves, dormers and tile-hanging, with two tall chimneys as the only bravura touch.

A sketchbook in the RIBA Drawings Collection records the young architect’s first thoughts for Munstead Wood. Lutyens had spent half a year in Ernest George’s office and perhaps it was there that he learnt his style. The ideas, albeit charmingly presented, did not meet with approval. Although Picturesque, the composition was too grand and there was a hint of Baronial in the interiors. In Home and Garden, Jekyll makes it clear there were many battles between architect and client — and also that she usually won them. Her desire was, above all, for simplicity, of a kind that would have puzzled her stiff-backed contemporaries. No drive came up to the house: from the lane, visitors entered by a wooden gate and walked the remaining yards to the door. This was one lesson she had for the young Lutyens.

The entrance itself, however, was pure Lutyens. No Lutyens house, whatever the style, reveals itself in an obvious or straightforward manner: visitors must go on a journey, which adds to the drama, as well as to the apparent extent of buildings that were not always big. Thus Munstead Wood presents first an arch, from which bands of tile radiate in a sunburst — a motif that became almost a signature of his garden architecture. Above are rows of what appear to be pigeon holes, perhaps intended for ventilation and conceivably derived from examples Jekyll had seen on her travels. This wall, however, turns out to be only a screen. Once through the arch, we turn through 90˚ and see the front door, beneath a dramatically over-structured oak frame.

Strangely, Jekyll’s own early thoughts for Munstead Wood involved marble. It was Ruskin himself who corrected her, writing in a letter that white walls and tapestries set the proper note for a house in a northern clime. By the time the design was finished, the elements were nothing if not local: rough Bargate stone, tawny coloured and impossible to square; clay tile roofs; oak frames to the doors and windows, with iron latches; brick and half timber in places. There were famously deep gables and sheltered, conversational spots.

The vernacular themes, however, were filtered through Lutyens’s architectural imagination. As did any architect of the day, he set out his façades using the tools available, principally T-square, set square and compass; so even the apparently vernacular elevations (Fig 4) conform to the basic principles of geometry. Squares and circles (in the form of old millstones) are seen in the garden, too. The sense of geometry is increased by the unbroken planes of the façades (Fig 3): it was a characteristic of the Surrey vernacular, seen in the photographs of Old West Surrey, that window frames are set flush with the wall (although protected at Munstead Wood by slightly projecting rows of clay tile). The doorway to the shop is combined with a window, under a single lintel — an idea that was Lutyens’s own. In the gable above, at Jekyll’s command, is a small opening, now a glazed window, but originally left open: it was to allow owls to roost in the attic.

Walking over from The Hut every day to inspect the work, she rejoiced in the sound of bricks being laid, from the ‘chop and rush of the trowel taking up its load of mortar’ to the ‘ringing music of the soft-tempered blade cutting a well-burnt brick’. She revered the old craftsmen at work on the house. An inscription to record the completion of the house on the north wall puts the builder’s name before that of Lutyens. Inside, oak would set the tone. Jekyll could remember the individual trees, which had been growing nearby, until cut down and planked some 15 years before. Lutyens’s joy in wood led him to apply some strange and seemingly unnecessary timber braces to the sides of the ground-floor hall.

That hall betrays Lutyens’s inexperience. In The Hut, the staircase had been next to the fireplace, a cottagey arrangement that does not seem suitable in the hall of the much larger Munstead Wood (Fig 8). Because the width of the room, combined with the low ceiling, created a rather dull space, Lutyens introduced timber braces at the sides; they have no functional purpose. Jekyll’s large work room opens off it, with a characteristic Lutyens fireplace (Fig 2).

On the half landing of the staircase is the book room where Jekyll wrote. The staircase itself is an open frame of Elizabethan type, but quite modest in scale (Fig 7). It leads, however, to the glory of the house: the broad first-floor gallery, its walls lined with oak panelling and display cases for Jekyll’s collections, the powerful oak beams overhead suggesting a forest (Fig 1). It was so successful that Lutyens reproduced it at Deanery Garden, the house in Berkshire that he built for Edward Hudson, the founder of Country Life, one of many important contacts for his career to whom he was introduced by Jekyll.

Fortunately, Jekyll’s house has survived without much alteration since Lutyens built it, but the labour-intensive garden was grassed over in the 1950s. However, when the 1987 hurricane brought down 200 trees on the property, the then head gardener Stephen King could see the outlines of the paths and borders and the owners, Sir Robert and Lady Clark, began a restoration campaign.

For the past 20 years, this has been taken forward by the present head gardener Annabel Watts, who notes that few gardens have been more thoroughly documented in both the written word and photography. Following Lady Clark’s death, Munstead Wood was put on the market in 2022, raising concern about the future of the garden and its accessibility by the public. In these photographs, Country Life has recorded the house as she left it.

Credit: Gertrude Jekyll's garden at Munstead Wood - photographed in 1908 (©Country Life Picture Library)

15 colour photographs from 1912 showing Gertrude Jekyll’s garden at the height of her fame

Credit: Peter Wright Photographer/Knight Frank

One of Lutyens 'most important country houses' — and the former home of Gertrude Jekyll — is up for sale for the first time in over 50 years

The Surrey Hills is very much Lutyens and Jekyll territory, notably at their first-ever collaboration at the garden designer’s home,

The Gardens of Greywalls: A Scottish masterpiece bearing the imprint of Lutyens and Jekyll

'Within a mashie-niblick' of the 18th green at Muirfield Golf Club lies a garden of great beauty and history, as

Mark Griffiths: Why gardening is vastly richer, wider and deeper than in Gertrude Jekyll’s day

Gertrude Jekyll loved bergenais, but she'd be the first to agree that the variety around today far outshines what was

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson