Mount Vernon: The story of George Washington's country estate

Jeremy Musson looks at the remarkable history and preservation of Mount Vernon, the country home of America’s first president, George Washington. Photographs by George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

Mount Vernon — the former home of George Washington, first President of the USA — is an extraordinary place; a dignified Virginian gentleman’s seat (Fig 1) overlooking the Potomac River that was built in several phases throughout the 18th century. With an exterior clad in timber, detailed and painted to appear like stone rustication, the house is probably the most intensely researched in America.

It has been the subject of a sustained preservation campaign, with a great deal of significant work taking place over the past 12 years; this is due for completion in 2026 and will be part of the 250-year celebrations of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

A final phase includes the reintroduction of a lost timber sole plate that will help underpin the structural integrity of the building for the next century. This is the first of two articles examining the history of the house and site as it moves towards the end of a major programme of repairs. The second article will focus on the restoration of the interiors.

Unsurprisingly, Mount Vernon has been a subject of fascination, mostly because of George Washington, major-general and commander-in-chief of the American or ‘Continental’ army that fought the British in the American Revolutionary War (as the War of Independence is now usually known), before becoming the first elected president of the new American nation (Fig 4). His character and values helped shape the fledgling country’s sense of self and he himself shaped Mount Vernon, providing designs for the house with his own pen, in the spirit of a gentleman amateur, and the provision of pattern-book exemplars for his craftsmen.

There can be little doubt that Washington adored Mount Vernon; late in life, he wrote of it: ‘No estate in United America is more pleasantly situated than this. It lies in a high, dry & healthy country […] on one of the finest Rivers in the world.’ The Washingtons were famously hospitable, with Washington describing his house — only half-jokingly — as a ‘well resorted tavern’ in 1787. By the time of his death, on December 14, 1799, Washington had devoted 45 years to the development of the estate, both the 8,000-acre plantation and the principal residence and parkland. After retiring from office in March 1797, he returned to improve both the farming and the house, partly in a self-conscious imitation of the ideal of Cincinnatus, the military leader of the early Roman republic who returned to his plough.

The house survived the American Civil War even when many older estate houses in the region were destroyed. Its preservation was due to a dedicated band of women — the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, which was formed in 1853 under the direction of Ann Pamela Cunningham, with representatives drawn from many of the original states of the Union. In 1861, during the Civil War, the Association petitioned military leaders on both sides and succeeded in having the site declared neutral ground, an event that deserves more study for how such historic buildings can be protected in wartime.

The same association, still with a woman only board, owns and manages Mount Vernon today, preserving it without state assistance and opening it to more than one million visitors a year. It has continued to enhance the presentation of the home of one of the founding fathers — perhaps the founding father — of the modern American nation. This work is supported by the outstanding facilities of The George Washington Presidential Library, also on the Mount Vernon estate. The house and its collections associated with the Washington family have been the focus of an extraordinary level of scholarly research, which has fed into redecoration work, following a guiding principle of presenting the site as it was at the death of Washington.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A museum, together with films and guides, helps visitors explore Washington’s life and values alongside those of the emerging American republic, encompassing new research, knowledge and understanding about the lives and contribution of the many African American enslaved servants and estate workers. The plantation and estate had an enslaved workforce of 317 at his death, typical of how an agricultural property in the American South or the British Atlantic colonies was then run. Washington was regularly accompanied by his enslaved personal manservant, William Lee, who is depicted with him in more than one portrait. His will freed Lee outright in recognition of his devotion during the Revolutionary War. The other slaves he owned personally were to be freed after the death of his wife, Martha, suggesting some ambivalence towards the system of slavery and the slave-based economy from which he and his estate benefited.

The Mount Vernon land belonged to the Washington family from 1674. Washington’s father, Capt Augustine Washington — a Virginian agriculturalist, JP and county sheriff — bought it from his sister in 1726 and had a new five-bay house built there, consisting of a single main storey with an attic, in 1734. George took over the estate from his older half-brother Lawrence and was a tenant until the death of Lawrence’s widow in 1761.

The young Washington was an army officer for the British administration during the 1750s war with the French. He was colonel and commander of the Virginian regiment in 1755–58 and married a young widow called Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759, gaining two stepchildren, to whom he was devoted. By the 1770s, Martha’s wealth had brought him to into the top rank of Virginian society. He was then embarked on a political career that would culminate in him becoming a commander of the American forces against the British and the first US President.

Mount Vernon was rather neglected during Washington’s presidency and he returned in early 1797 to find the house ‘in need of repairs’, describing himself in April of that year as ‘surrounded by Joiners, Masons, Painters &ca’. The house had been raised by a storey in 1758–59 to create a new first floor and attic and, in the late 1770s and early 1780s, his cousin and agent, Lund Washington, had to oversee the work when Washington was away fighting the British. Extended to both the north and south, the house reached its full physical extent at nine bays wide, with a double-height portico running its length, in a simple Tuscan order derived from a design by Batty Langley. Complete by 1777, the portico — always known as the piazza, its name apparently derived from the piazza of London’s Covent Garden — became the place where visitors enjoyed views of the river and cool evening breezes.

Two three-bay pavilions of 1½ storeys were added in 1775–76 on the entrance — and landward — side of the building (Fig 3); these were linked to the main house by unusually open, curved colonnades, the pavilions replacing outbuildings built by Washington’s half-brother. One pavilion housed a kitchen; the other, the servants’ hall. Further distinction to the entrance elevation was conferred by a triangular pediment over the entrance and an octagonal lantern known as the cupola. Both these details helped disguise the asymmetry of the elevation, which followed the placement of the stair in 1734.

In 1787, Washington designed and built a brick greenhouse (Fig 5), filling it with lemons, limes, aloes and palm trees. Low wings on either side housed some of the enslaved workers of the estate; men on one side, women on the other. Although later damaged by fire and rebuilt in a different form, this building — both orangery and wings — was reconstructed to its original appearance in 1950–51. Housing for enslaved families, now lost, was also provided in cabins near the greenhouse.

Washington was a land surveyor by training and, by conviction, an ‘improving’ farmer, who was always on the look out for clever solutions. He considered it ‘within the rules of architecture… to make such small departures’ as were necessary for a pleasing result. As well as providing a simple sketch for the 1770s additions, he designed a 16-sided threshing barn for processing and storing grain. This was built by estate carpenter Thomas Green, who worked at Mount Vernon in 1782–94. Green’s team of enslaved carpenters included African-born Sambo Anderson, who also worked on alterations to the main house. The barn was later lost, but a replica was built in 1996, on a site nearer the house.

Visitors to the estate were very conscious of the status of Washington and many recorded their impressions in detail. In 1785, Robert Hunter wrote: ‘I rose early and took a walk about the general’s grounds, which are really beautifully laid out… [he] superintends the whole himself. Indeed, his greatest pride now is to be thought the first farmer in America. He is quite a Cincinnatus, and often works with his men himself, strips off his coat and labors like a common man.’ Astonished by the size of a small estate village of workers’ houses, Hunter noted: ‘He has everything within himself — carpenters, bricklayers, brewers, blacksmith, bakers, etc.’ Hunter admired the way Washington knew how to ‘prefer solid happiness in his retirement to all the luxuries and flattering speeches of European courts’.

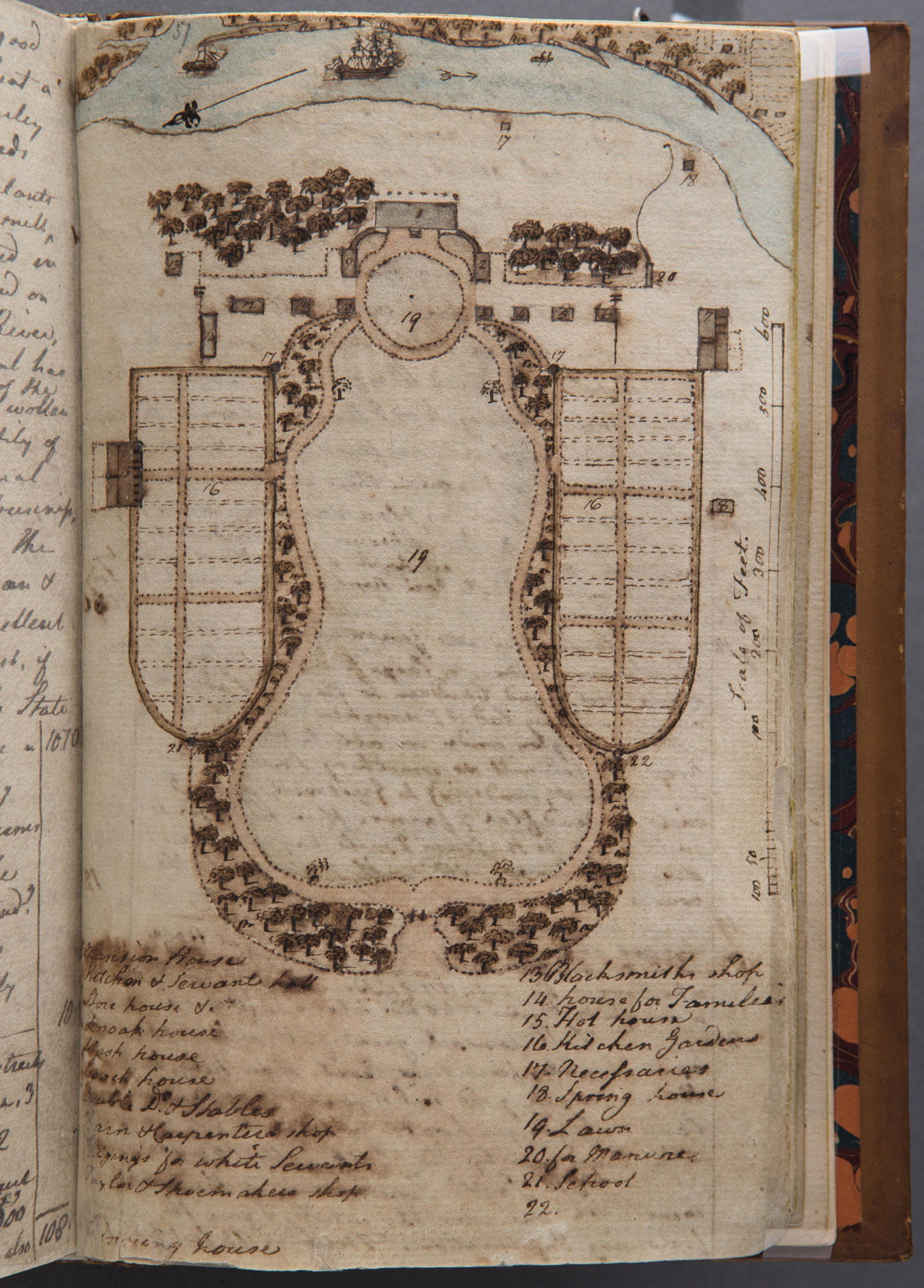

English visitor Samuel Vaughan made a sketch survey of the grounds in 1787 (Fig 2). It shows the extent of the house, the planting, the parade of outbuildings, workshops and dwellings — still present today (Fig 6) — and the parklike quality of the approach. Vaughan presented Washington with a fully drawn-up version of this, which has been an essential reference point for the estate as a protected monument. He noted ‘a street is formed on each side at right angles above 200 feet long in which are sundry houses for domesticks Tradesmen Workshops etc’. Some of these have survived, others reconstructed.

The main house is compact in the centre, with the piazza to the east described by a visitor in 1796 as ‘the general resort in the afternoon’. The entrance hall forms an east-west central passage through the house and, leading directly off it, are four intimate sized rooms. On the north side are the Front Parlour and the Little Parlour and to the south are the dining room and a principal guest bedchamber.

Additions in the 1770s include Washington’s study to the south and the notable room known as the ‘New Room’ to the north. In reference to this, Washington wrote: ‘I would have the whole executed in a masterly manner.’ This double-height room has a Venetian window, with its exterior character taken directly from plate 51 in Langley’s Treasury of Designs, 1750, copied faithfully by estate carpenter Goin Lanphier.

Visiting in 1798, Polish aristocrat Julian Niemcewicz described the New Room as a ‘large salon… recently added’. Of the wider estate, he observed: ‘In a word the garden, the plantations, the house, the whole upkeep proves that a man born with natural taste can divine the beautiful without ever having seen the model. The Gl. [General] has never left America. After seeing his house and his gardens one would say that he had seen the most beautiful examples in England of this style.’

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, a British architect recently settled in Virginia, was more circumspect, commenting in 1796 that: ‘Along the other front is a portico supported by 8 square pillars, of good proportions and effect.’ Although noting an expensive marble chimneypiece ‘in the taste of William Chambers’ in the New Room, he added: ‘Everything else is good and neat, but by no means above what would be expected in a plain English country gentleman of £500 or £600 a year. It is however, a little above what I have hitherto seen in Virginia.’ We will look at the rich and complex story of the interiors of Mount Vernon in next week’s article.

Acknowledgements: Thomas Reinhart Visit www.mountvernon.org

Credit: Country Life / Whitehouse.gov

Donald Trump's new home: 100 years of change at The White House

In December 1916 Country Life magazine was granted extraordinary access to The White House.