Mount Grace Priory, North Yorkshire: Cloistered from the world

This magnificently preserved charterhouse offers a compelling insight into late-medieval English monasticism.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

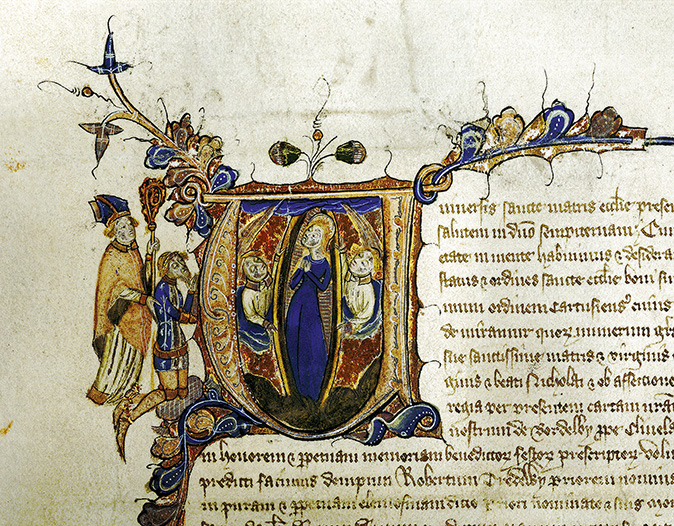

In 1398, by permission of his uncle, Richard II, Thomas Holland, Duke of Surrey, established a monastery of Carthusian monks in the manor of Bordelby, North Yorkshire. According to the terms of his foundation charter, the Duke acted out of his particular admiration for the religious life of the order. He ordained, moreover, that the institution be called the Priory of Mount Grace of Ingleby and that it was to be dedicated with reference to his particular devotions to St Nicholas and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Listed among the beneficiaries of its prayers were the King, the Duke, a small circle of his relatives and a number of Yorkshire gentry, including several members of the Ingleby family, tenants of the manor.

The new monastery was established within the embrace of a moorland escarpment a short distance from the main road between York and Durham. That road has since swelled into a four-lane artery and its roaring traffic has cut the priory ruins off in a small rural oasis. The modern isolation of the site is, in some ways, very appropriate, as Mount Grace is the most completely preserved medieval Carthusian monastery – or charterhouse – in Britain, an order celebrated both for the strictness of its religious life and the eremitical existence of its brethren.

The Carthusian order was a product of the great late-11th-century tide of monastic enthusiasm that also brought into being the Cistercians. Only 10 charterhouses were ever successfully founded in England, however, the bulk of them from the mid 14th century onwards. In the case of Mount Grace, it is actually very difficult to identify the motive forces behind its establishment. It is easy to imagine, for example, why the local figures mentioned in the foundation charter might have needed the backing of the Duke to establish a monastery, but why did he need them?

No less curious is the proposed title of the foundation. Does ‘Mount Grace’ merely allude to the pursuit of spiritual improvement? And why ‘of Ingleby’?

It is to speculate beyond the available evidence, but one possibility is that the monastery was, in fact, an adjunct to an existing chapel: in 1397 or 1398, John Ingelby received permission to hear offices in a chapel or oratory in the manor of Bordelby. Might this be one and the same as a chapel that still exists on the hill immediately above the monastery?

This is first securely documented only in 1520 and, as ‘The Mount’, was assigned to the prior at the suppression of the monastery. Could the hill and the chapel, therefore, be the eponymous ‘Mount’ of the priory name?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Within a year of its establishment and generous endowment with land, Richard II was deposed. The following year, the Duke, having been demoted to the status of an Earl, was executed and the monastery looked about for a new patron. After a period of difficulty, the uncle of Henry V, Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, stepped into the role in 1415 and secured the right to be buried here. Following his death in 1426, the Ingleby family assumed the patronage of the house.

Thereafter, the monastery began to expand and enjoy considerable local patronage. In 1535, its annual income was estimated as £323, slightly less than the £351 of the great Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx about 10 miles away. It could hardly have looked more different. In comparison to the massive grandeur of Rievaulx, Mount Grace was low-built and castle-like, protected against the world by encircling walls and a wider enclosure defined by ditches. For this was, paradoxically, a community of hermits, each monk accommodated within his own cell and garden.

Detailed archaeological excavation of the site both by Sir William St John Hope from 1896 and more recently, from 1957 to 1992, by the Ministry of Works and English Heritage has fleshed out our understanding of the site and its medieval history.

The overall plan of the monastery seems to have been determined when the community first arrived, although the first generation of buildings erected was timber-framed and occupied only a fraction of the site. These were gradually redeveloped in stone, with additional cells being added as the community expanded from nine in 1412 to 16 (a full complement) at the surrender of the Priory in 1539.

The medieval visitor entered the monastic complex through a surviving gateway built through the middle of a long guesthouse range that defined the complex to the west. They emerged into a court lined to their right, on the east and south, by service buildings, including a granary stable and brewery. To their left, screened by a small cloister and the hermitage cells of the junior monks, termed novices, was the monastic church.

Because the monks said much of their Divine Service alone in their cells, this building is unexpectedly diminutive in size. It began life as a rectangular box, but was expanded by degrees to incorporate several additional chapels for the burial of patrons. In the late 15th century, the choir and nave were internally divided by a stone cross passage surmounted by a belfry tower. The form and position of many internal fittings, including a rood loft, can be inferred from fixing sockets in the walls. There was a tile floor in the choir (in contrast to the stone-flagged nave) and high-backed stalls. A coved wooden roof covered the choir interior, which also gave access to the monastic chapterhouse.

Beyond the church, to the north of the site, lay the great cloister, a garden and cemetery enclosed on four sides by a covered walkway. Opening off this were the cells for the monks. Each occupied a little house set within its own walled garden. The arrangements of these vary slightly, but they comprised three ground-floor rooms – a living room with the fire, a study and bedroom oratory – and a workroom above.

Throughout the Middle Ages, standards of domestic comfort in monasteries tended to keep pace with those of prosperous people in the secular world. Consequently, the cells were boarded for warmth and the windows were glazed and shuttered. Opening off the ground floor in each case were two covered walks, one leading to latrines in the outer wall of the garden and another glazed for private exercise and meditation.

Because Carthusian monks did not usually eat together communally, there are small openings through from the cloister walk into every cell. This allowed for the delivery of food from the monastic kitchen without any communication. Each cell was also supplied with running water piped from a cistern in the centre of the cloister. One notable austerity of Carthusian life was that they drank water rather than the medieval staple of beer. Clean water for drinking was essential, therefore, and supplied in this case by the springs from the escarpment that embrace the site.

One of the cells was re-roofed and restored between 1901 and 1905. This building was then furnished and adapted on the basis of archaeological information in the late 1980s to give an impression of what a monk’s cell might have looked like in the early 16th century. Confusingly, the restored cell was the last to be built in the entire complex. As such, it departs in some particulars from the other, earlier cells on the site. Nevertheless, it captures a sense of the scale of these interiors – perhaps flavoured a little by the spirit of the Arts-and-Crafts movement – as they might have appeared in the late Middle Ages.

We do know a little about some of the men who entered into the community at Mount Grace from documentary evidence, surviving texts and from archaeological finds. They included well-educated men from prosperous backgrounds.

The south cloister walk of the Great Cloister gave access to the church and the refectory. For convenience, the refectory connected directly with the kitchens, which, in turn, adjoined the guest hall for visitors. The kitchens comprised two discrete areas, one for fish and the other for meat. The Carthusians ate no meat, so the latter only supplied the guest hall. Curiously, scraps and bones were routinely trampled into the floor of the fish kitchen. Excavating this area has offered fascinating insight into the diet of the monks. Seal was evidently consumed as fish, for example. One of the most surprising finds was a human toe, presumably cut off by accident.

Also accommodated within the south cloister range were the cells of the prior, who ruled the monastery, and the Sacrist, one of the senior monks. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the range was reconfigured to accommodate two additional cells. These were botched into the space between the church and the cloister, evidence for the continued appeal of Carthusian monasticism.

By virtue of the popular respect accorded to them, the Carthusians were the object of particularly brutal treatment by the authorities during the 1530s. Mount Grace was suppressed in 1539 and the community pensioned off. The experience of one former monk has been imaginatively evoked in The Time Before You Die (1999), a historical novel by Lucy Beckett.

It is noteworthy that the excavation of one cell revealed a pile of crockery deliberately shattered piece by piece against one of the walls. Was this the act of an enraged departing monk or a malicious vandal? What happened to the buildings in the aftermath of the Dissolution is not merely uncertain, it is a little mysterious. Many Yorkshire monasteries were immediately defaced, yet, at Mount Grace, even the church and its tower were left standing.

The estate passed quickly through the hands of three owners before it was sold in 1544 to one Ralph Rokeby. It then passed by the marriage of his granddaughter, Grace, to her husband, Lord Darcy, in October 1616. The couple was probably responsible for recasting part of the guest range as a house. Then, in 1653, the property was sold to Capt Thomas Lascelles, a Parliamentarian soldier, whose family sold it to the Mauleverer family in 1744.

From the 18th century, the Jacobean house was probably continuously leased out and it became a farm. Towards the close of the 19th century, it passed by descent to the antiquary William Brown, who undertook the first investigation of the site from 1896. Two years later, Mount Grace was sold to the industrialist Sir Lowthian Bell. His transformation of the site will be the subject of next week’s article.

Meanwhile, the chapel known as the Mount or Lady Chapel enjoyed a remarkable and independent history as a centre of Catholic pilgrimage and devotion. In 1535, a monk of Jervaulx, George Lazenby, was moved by a vision he experienced here to defend the power of the Pope (for which he was executed). Whether connected to this episode or not, the practice of pilgrimage here was sufficiently well established by the early 17th century to be a matter of concern to the authorities and has continued unbroken to the present.

In 1959, work began to restore the chapel, which was re-consecrated in 1961. It is an evocative but modest building, now maintained by the Diocese of Middlesborough and is open every day.

For further information, visit www.english-heritage.org.uk

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.