Minterne Magna: The early 20th century transformation spearheaded by a radical architect to who turned his hand to creating a cosy, beautiful home

We delve into the archives to enjoy the tale of the early-20th century rebuilding of Minterne Magna in Dorset.

Every week, we take a look at a house featured in Country Life’s unmatched archive of architectural content. This week, it’s a piece from exactly 40 years ago in which Clive Aslet — who would go on to become editor of the magazine — took a look at the early-20th century rebuilding of Minterne Magna in Dorset.

Leonard Stokes was a radical architect.Advanced principles do not always coincide with the comparatively homely virtues of comfort and warm-heartedness, however, and that Minterne Magna breathes exactly these qualities is a tribute to the architect. It is also a reflection of the happy atmosphere of his clients' household.The 10th Baron Digby led a life typical of many English gentlemen at that time, His day was divided between field sports and public duty, as a magistrate or on the County Council. Going to London was something of an event. Perhaps it is surprising that Minterne so largely evokes the 10th Baron and his wife; yet the domestic tenor of their lives makes it entirely appropriate that they should be remembered through their home…

Clive’s article delves into the family history, ending with an account of how the 9th Baron decided to expand the house:

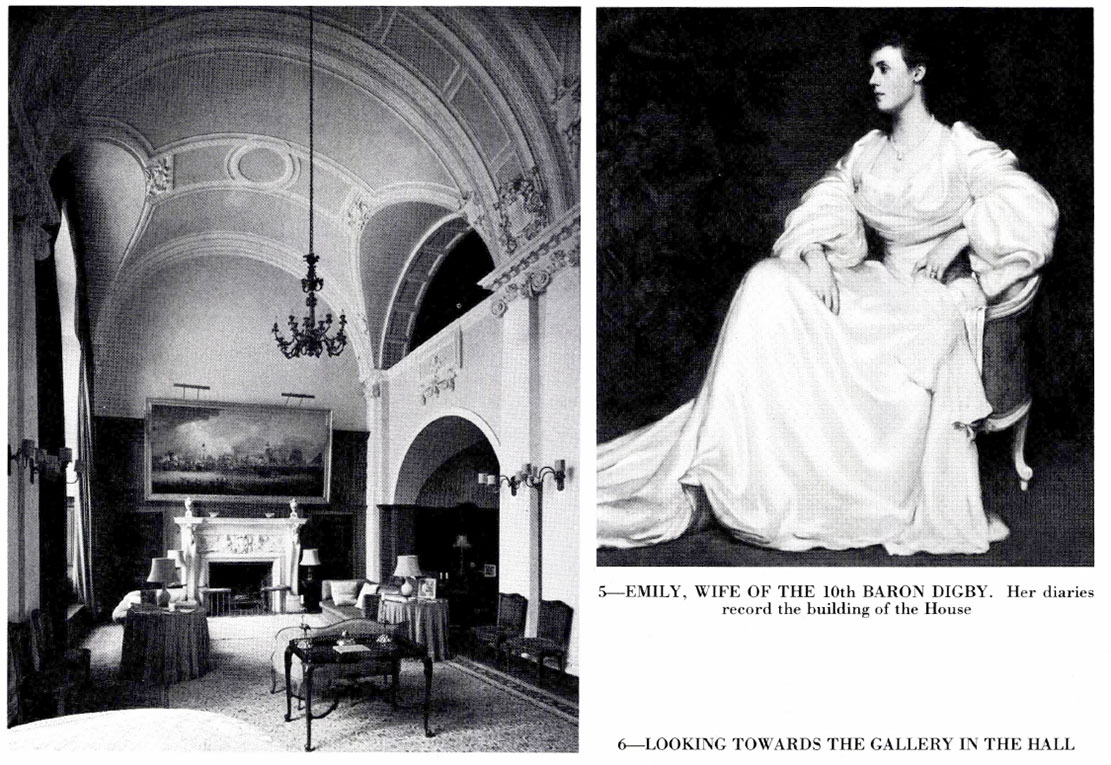

An obscure architect called L. B. Lamb (perhaps a relation of Edward Buckton Lamb?) received the commission, and undated drawings show that originally a complete transformation was contemplated.All the windows were to be given keystones and ears, and a French Renaissance-style tower added in the centre of the garden front. Photographs show that the plan was modified. The old house was not altered, externally at least, except for the roofs; here dormers were added for more servants' bedrooms. The tower was built not centrally but at the west end of the house, with a two-bay addition beyond it.Style and scale clashed on the garden front, and the entrance front was worse.One could not blame Minterne's next owner, Edward Henry Trafalgar, 10th Baron Digby, who inherited in 1889, for wanting to rebuild it. When he did so, however, his motives were far from purely architectural, He married late, at the age of 47. His wife, Emily Hood, was 25 years younger.Family tradition has it that, newly married, she persuaded him to rebuild; he acquiesced, but insisted that it should be done out of income, not capital, so they waited nine years before undertaking the work. That may be so, but Lady Digby's diaries leave no doubt that the enterprise was hastened by circumstances neither of this ideally sensible couple had foreseen.

Her entry for February 22, 1902, sounds the first ominous note.‘Eddy and I’, she writes, ‘had to turn out of our bedroom as a horrible smell turned up in the middle of last night which we think must be a dead rat in the wall, but at present we cannot trace it.’Four days later the smell was worse, spreading downstairs to the tapestry room (then used as a school room) . The 'blue bedroom’ into which they had moved was also smelling ‘very funny, dryrot we think’. On the 26th she found the tapestry room smelling strongly of gas — ‘they fear something wrong with the drains’. Nine days later a hitherto unknown barrel drain was discovered, which was thought to be part of the trouble.All in all there were grounds for serious consternation. ‘Eddy is much troubled as to what ought to be done. He feels the house is not worth spending a big sum on, and he feels it must be a big business, what with drains, dryrot and rats in the house.’

It was at this point that Leonard Stokes was brought in:

On June 18 ‘Mr L. Stokes, architect, arrived to look over the house and report also he has taken plans we have worked out, with the idea of possible alterations to the old house and he is to work out our scheme more fully’. At this stage they still hoped that it would not be necessary to rebuild completely.It is not clear why Lord Digby went to Leonard Stokes. He was not an obvious choice of architect, his practice being largely ecclesiastical, building austere churches, externally often striped in bands of brick and stone.Another type of work, still unrelated to country houses, had been growing in importance since his marriage in 1898. His wife, Edith Gaine, was the daughter of William Gaine, general manager of the National Telephone Company. In 10 years, until Gaine's death in 1908, Stokes received 20 commissions for telephone exchanges.

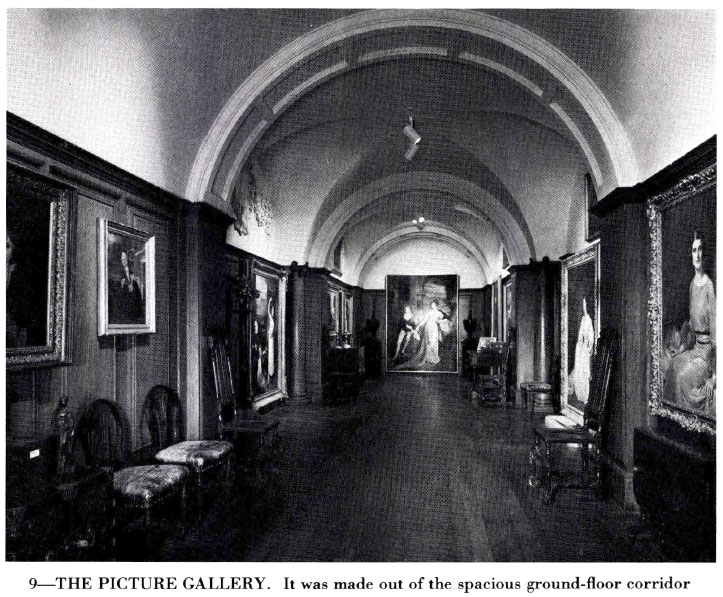

Stokes's experience of country house work was limited. In 1893 he had designed a rambling house called lnnisfall, on Loch Allen, in Co. Leitrim. Like Minterne, it drew on a number of styles, but the effect was looser and the plan almost wilfully perverse. His best country house before Minterne was Shooter's Hill, Pangbourne, in Berkshire, built for D. H. Evans of the Oxford Street store. Gabled, built out of two shades of red brick and with a profusion of white-painted sash-windows, it falls in style and date halfway between Queen Anne Revival and ‘Wrenaissance’. That is in itself, in the late 1890s when it was built, a mark of the architect's individuality.Stokes's verdict on Minterne's condition cannot have been favourable; it was soon decided to rebuild the house, not just alter it.By May the next year, 1903, Minterne's contents were gradually being put into store, the best pieces going to Lord Digby's town house in Belgrave Square. A special excursion to London was made ‘to see Leonard Stokes about the plans — also to bustle him up a bit’. The housekeeper and the head-housemaid stayed in the increasingly empty house until August, when the builders took over. A cottage, formerly the stud groom's, was furnished for the Digbys to use when they visited the site.The foundations were ready by Whitsun 1904. About 10 feet of wall had gone up by November. A year later the roof was watertight, the porch was being built, and two staircases were in place. No house has been built without delays, however. In 1906 the firm that supplied the window-frames was ‘being very tiresome’; the heating was started late, so the plaster could not dry, which meant that the joiners could not start; the drawing-room ceiling had to be taken down and remade. Scaffolding still in the drawing room meant that the Thornhill ceiling could go up in the dining room as it could only be got in through the drawing-room double doors. On October 18, 1907, Lady Digby spent her first night in the new house…

Clive goes on to discuss the hard work undertaken by Lady Digby, who herself worked on the needlework on the house:

We are accustomed to think of the Edwardian age as one of luxury. It was, and Minterne was like any other large house of that date in having a sizeable staff of servants to run it. But it was not only the servants who worked hard. The diary reveals that nearly all the needlework in the house was made by Mrs Sims, the odd man's wife, and Lady Digby herself, working tirelessly from October 1907 to August 1908. Except ‘for an occasional seam in some of [the] curtain linings, by a housemaid and that very badly done unless I had my eye on it the whole time’, they ‘ made every curtain chair and sofa cover, bed valences, in fact everything but the three big Hall curtains, which I had made and sent from London’.

The house was in some ways an update, in other important respects a new home:

Something of the old Minterne passed over to the new. The tapestry room was 'practically a duplicate’, including the bow-window. Stokes reused the existing foundations, so that the plan changed very little in outline (the only departure being the billiard room at the end of the garden front, which was set at a characteristically Edwardian angle) . Indeed, some details suggest that Stokes emphasised the continuity; for instance, the box porch on the entrance front looks very like that on the old house.But in style Stokes was wholly original. His imagination roamed freely through the gamut of styles, and he took what he wanted.Incompatible details are brought together in the same facade: the entrance front has a hood over the front door derived from 18th-century examples, Perpendicular tracery in the windows beside it, vestigial machicolation along the parapet and chimneys reminiscent of Hawksmoor.

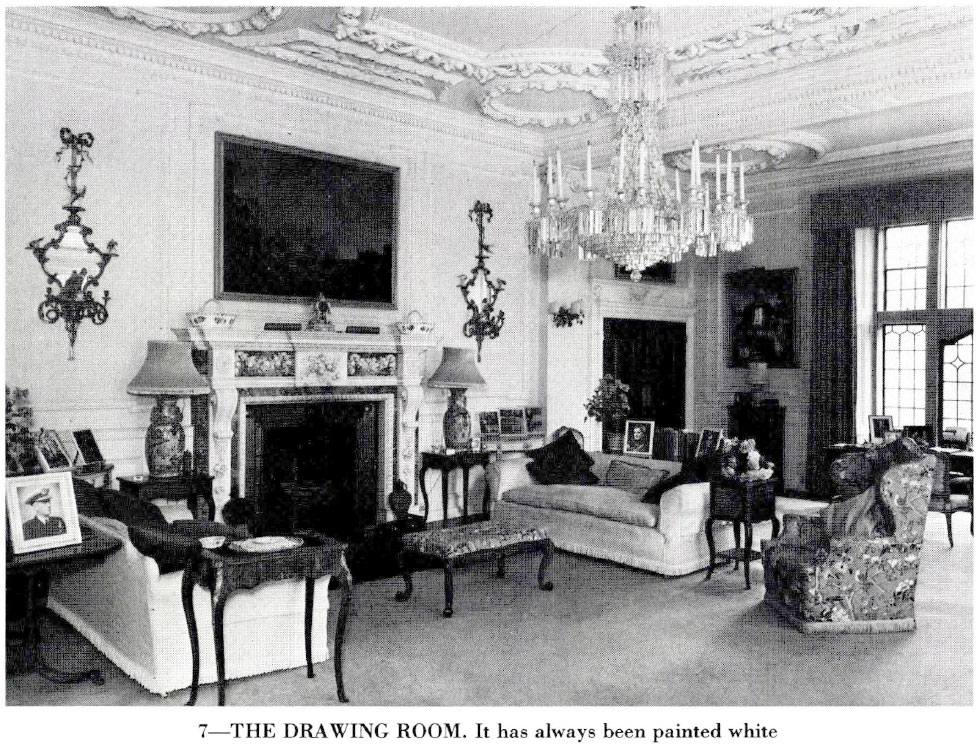

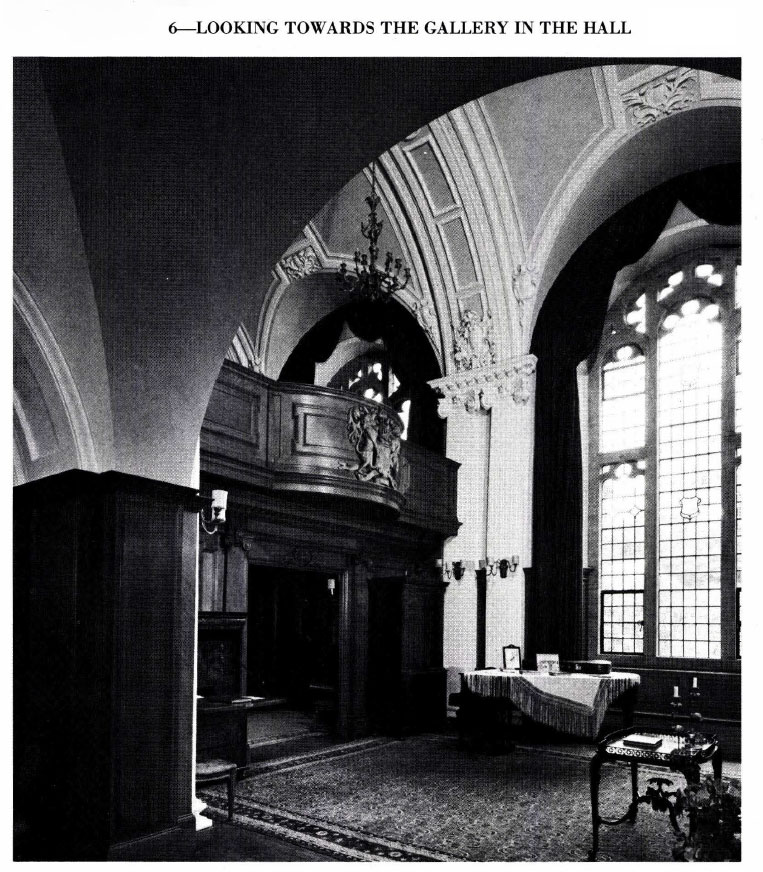

It is all unified by the rhythm of the buttresses between the bays, and the spareness with which all the details are conceived. Like many of his more advanced contemporaries, Stokes felt he could draw freely on details from the past in the creation of a modern style.Both facades are undeniably stern. Mouldings have been pared down to the simplest forms, and incised lines take the place of ornament. All of which makes the light and space of the interior a greater contrast.Most of the main rooms — the billiard room, dining room, study and drawing room — are along the south front. They are connected by a corridor so ample that, when the present Lord Digby divided the western part of the house into flats, half its length was turned into a picture gallery. At least some of the rooms have always been painted white — the drawing room was, ‘on account of the pink silk curtains and furniture being such a strong colour’. It made an already generously lit and sunny room still lighter, which compensates for any suggestion of heaviness in the stucco work.The interiors are classical. The drawing room re-uses an 18th-century fireplace, presumably from the old house. But the classicism does not extend to the plan. This is made up of elements familiar from Victorian country houses, but used to quite different effect.The two-storey ‘main hall’ is the key to the change. It is essentially medieval in concept: the entrance vestibule, which connects with it at the western end, reads as a vestigial screens passage; the gallery over this suggests a minstrel's gallery; the hall has mullioned windows with Gothic tracery.

However, most Victorian great halls — and those of Stokes's contemporary, Ernest George — were intended to exude some degree of baronial flavour by use of extensive oak panelling, armour and a massive fireplace. At Minterne, Stokes killed any hint of medievalising mustiness by giving the room plasterwork from the age of Hawksmoor. The ceiling has a barrel vault, and two arches open onto a passage or gallery on the southern s1de. This passage opens into the entrance hall, which in turn gives onto the garden, creating a flow of space reminiscent of Baillie Scott.

The house was fully completed in the summer of 1908, with the Digbys throwing a garden party to celebrate the conclusion of this huge project:

Not everything the guests could see was new, however.The landscape, planted by Admiral Robert Digby in the late 18th century, was mature, and the rhododendron garden had been laid out in the 1890s.It was, therefore, ready to receive the new varieties of rhododendron and azalea introduced to this country in the early 20th century. Expertly tended since then, it now perfectly complements the Edwardian house.

Houghton Hall, Norfolk - II: A Seat of the Marquess of Cholmondeley by John Cornforth

From the Country Life Archive: John Cornforth discusses how the architectural decoration of the piano nobile at Houghton is complemented

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Voewood, the 'supreme example' of a butterfly-plan house in Norfolk's beloved Poppyland

Country Life's Mary Miers praised the eccentricities of the Arts-and-Crafts style in a piece from our archives published in 2009,

The oldest house in Britain — and how we were able to tell it apart from the other contenders

There are many nominations for the oldest home in Britain — in this piece from the Country Life archive, John Goodall

Cumberland Lodge: The 17th century marvel 'a thousand times more agreeable than Blenheim'

This year, a remarkable educational foundation in a spectacular parkland setting celebrates its 70th anniversary. John Goodall considers the history

The tale of the fire that turned Cowdray's ancient castle to ruins, the treasure hunters who made it worse, and how what was left was saved

-

New balls please: Eddie Redmayne, Anna Wintour and Laura Bailey on the sensory pleasures of playing tennis

New balls please: Eddie Redmayne, Anna Wintour and Laura Bailey on the sensory pleasures of playing tennisLittle beats the popping sound and rubbery smell of a new tube of tennis balls — even if you're a leading Hollywood actor.

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee

-

A rare opportunity to own a family home on Vanbrugh Terrace, one of London's finest streets

A rare opportunity to own a family home on Vanbrugh Terrace, one of London's finest streetsThis six-bedroom Victorian home sits right on the start line of the London Marathon, with easy access to Blackheath and Greenwich Park.

By James Fisher