London's Lost Interiors: Inside the houses of the capital's plutocrats in the days when money was literally no object

A new book, 'London: Lost Interiors', explores the lost riches of London’s grand houses. Its author, Steven Brindle, looks at the residences of plutocrats built by the nouveaux riches of the late-Victorian and Edwardian ages, using wonderful images preserved in the Historic England Archive.

London has always been a magnet for the rich and super-rich, but, in the 1880s, there was an important shift in the character of this group. The landed aristocracy, who had long presided over London Society, saw their income fall as a consequence of Britain’s free-trade policies and the agricultural depression. At the same time, growing foreign trade and the expanding Empire created new fortunes in larger numbers than ever. With wealth drawn from across the world, these plutocrats were a more cosmopolitan elite than Britain, or any other nation, had ever seen before.

Their opulent houses were designed as settings for lavish entertainment and their aim was to gain acceptance in High Society. Generally speaking, the strategy worked, helped in some cases by the friendship of the Prince of Wales, a lover of luxury. Many of the richest plutocrats established themselves in the old West End, centred on Mayfair and St James’s. The area was not big enough to house all of them, however, and the later 1800s saw fashionable London spreading westwards.

Although many lost aristocratic mansions are still remembered, such as Devonshire, Norfolk, Chesterfield and Lansdowne houses, their vanished counterparts built by plutocrats are much less well known. Who were these people and what did they build? It is possible to answer this question thanks to historic photographs, principally from the archive of Bedford Lemere & Co. Bedford Lemere (1839–1911) established his firm in 1861: he and his son, Harry (1865–1944), ran the company until the Second World War. Fortunately, their archive was acquired for the National Monument Record, now the Historic England Archive. Some 21,800 glass plate negatives and about 3,000 prints are stored at Swindon, providing a window into the past that is rivalled only by the archives of Country Life itself. There was a fashion among the wealthy for having their homes recorded, although the photographs were usually not intended for publication. Today, they are a precious historical record.

At the time, a traditional Georgian terrace house of the First Rate would still be deemed a suitable home for older families from the gentry or the upper-middle-classes, although such houses were often rented for the Season, rather than owned. However, houses of this kind, such as the ones that line Harley Street or Bedford Square, were generally not big or distinctive enough to satisfy a newly rich family looking to make its mark.

Plutocrats tended to buy the lease to a Georgian house and rebuild it or look for one of the much larger houses that had been built in about 1830–80. Many streets in Bayswater and Kensington, including Lancaster Gate, Princes Gate and Queens Gate, are still lined with such houses, rising five or six storeys high. The plutocrats’ homes tended to be on a grander scale than Georgian houses, with bigger basements and attics, capable of housing more servants. They were more likely to have modern conveniences, such as plate-glass windows (without glazing bars), electric light, central heating, conservatories and elevators.

The newly rich were cosmopolitan. Their wealth came from around the world and their homes often reflected Continental styles of decoration. No 4, Hamilton Place, near Hyde Park Corner, is a case in point. The mid-Georgian terrace house here was replaced in 1903–05 with an edifice of wedding-cake opulence for Leopold Albu (1861–1938). In 1876, he and his brother had emigrated from Germany to South Africa, where they made a fortune dealing in diamonds, claims and shares. They sold their company to De Beers, became British subjects and Leopold moved to London in about 1900. The Albus’ drawing room (Fig 3) was a skilfully-managed exercise in Louis XV style full of French furniture — either original pieces or good reproductions, such as the commode in the style of Jean-Henri Riesener seen to the left. The house is today the home of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

In the early 1800s, 18th-century French interior design and decorative art represented a specialised taste, shared by George IV and a few cultivated aristocrats. The style was popularised in the mid 19th century, in particular by the Rothschilds, and became standard features of plutocratic mansions. Designers and decorators were established to provide such things, notably a French firm, Charles Mellier & Co, which may have been involved in the Albu house and certainly worked for Sir James Miller, baronet, at 45, Grosvenor Square. The Millers had made a fortune as merchants, trading in the Baltic and Russia, but Sir James was a soldier and a Society figure, not a businessman. He married Lord Curzon’s sister, Eveline, and they later rebuilt their country house, Manderston in Berwickshire, but the London house came first, an indication of their priorities. Originally built in 1802, it was renovated in 1902–03 in the French taste, whereas Manderston’s interiors are in a rich Adam style. The beautiful conservatory (Fig 5) shows why Mellier & Co was so successful, yet the house was demolished in 1938.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The newly rich included ship-owners, such as the Wilson family of Hull. Charles Wilson, later Lord Nunburnholme (1833–1907), bought the lease to No 41, Grosvenor Square in about 1882. The existing house was too small and it was rebuilt in 1883–86 in Jacobean style by the architect George Devey with a ballroom, a great social asset that could not be accommodated in a Georgian terrace house. It seems unlikely, however, that Devey, who was noted for his sensitively designed Arts-and-Crafts houses, was responsible for the astonishing interior.

The ballroom was in an elaborate German Rococo style (Fig 1), reminiscent of Ludwig II of Bavaria’s palaces at Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee: it may be that a German designer and craftsmen were involved. The gilt chairs could be set out for concerts and recitals or ranged around the walls for balls. The house was remodelled for Nunburnholme’s daughter and her husband, Lord Chesterfield, in the early 1920s. By then, the wildly Rococo room had become too much to take and it was redecorated in a French 17th-century classical style. The house was demolished in the 1960s.

Lord Nunburnholme’s brother Sir Arthur Wilson owned Tranby Croft, the country house in Yorkshire that became notorious for a gambling scandal in 1890 that touched the Prince of Wales, one of the guests. In the same year, Sir Arthur bought the lease of 17, Grosvenor Place, one of a row of huge terrace houses built in about 1868, and renovated it. Stylistic variety was a feature of plutocrats’ houses: the house has a Louis XV drawing room and ballroom, whereas the dining room is in an English, late-17th-century manner (Fig 6). More ‘masculine’ styles were often adopted for halls, dining rooms and male preserves, such as billiard and smoking rooms. The house is now the Irish Embassy.

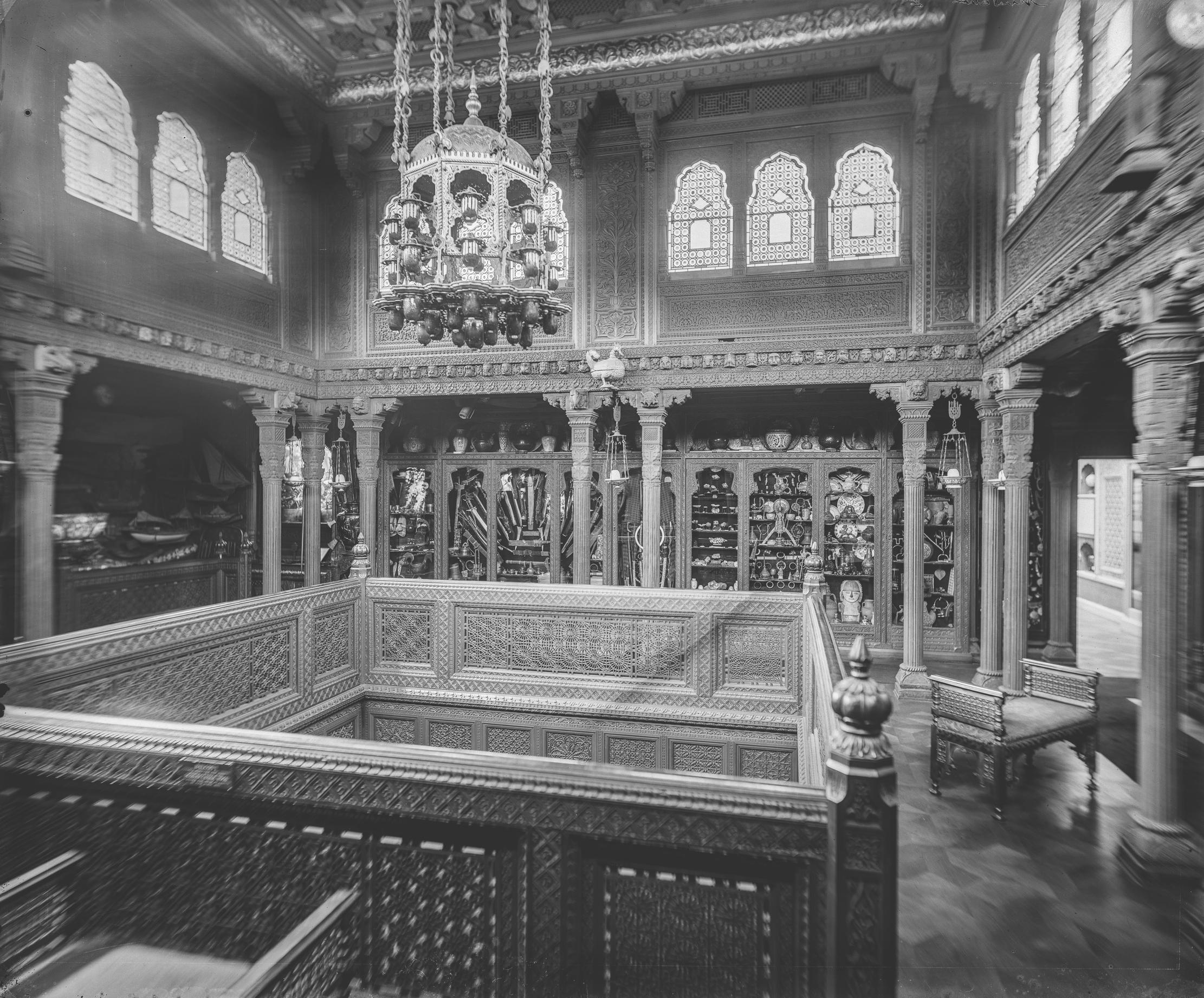

Many fortunes were based on engineering and contracting, one of the largest being that made by the great contractor Thomas Brassey. His three sons left the business, bought country estates and went into Society, in what became a familiar pattern. Thomas, 1st Earl Brassey (1836–1918), was a Liberal politician and noted yachtsman who built a big new house in a rich Italianate style at 24, Park Lane. Lord and Lady Brassey circumnavigated the world in their steam-assisted yacht Sunbeam in 1876–78 and formed a collection of Indian works of art and weapons.

The pair bought two pavilions lined with woodwork in Rajput style, which had been designed by Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke and made by Indian craftsmen for the Indian and Colonial Exhibition in South Kensington of 1886. These were remodelled as a top-lit room, built behind their house to display the collections as an ‘Indian Museum’, which was open to groups by arrangement (Fig 2). After Lord Brassey’s death in 1918, his son presented the room to the borough of Hastings and it was rebuilt, as the ‘Durbar Hall’ in the museum in the East Sussex town, where it may still be seen. The London Hilton stands on the site of the house itself.

American millionaires played an important role in late-Victorian and Edwardian Society. The phenomenon of financially embarrassed aristocrats, including the Dukes of Manchester, Marlborough and Roxburghe, marrying American heiresses is well known. George Cooper (1856–1940), a Scottish lawyer, was made a baronet in 1905. He had gained a fortune by marrying Mary Emma Smith of Chicago, the heiress to her railway-baron uncle. The Coopers bought a country house and estate at Hursley in Hampshire, together with a London house: No 26, Grosvenor Square. This stood on the site of Derby House, a masterpiece by Robert Adam that was considered too small by Victorian standards and was replaced with a larger, yellow-brick Italianate house in 1862.

By 1900, this was, in turn, unfashionable and the Coopers had the building renovated by Howard & Sons, another smart firm of decorators. Works of art were supplied by the dealer Duveen Brothers, which was rising on the tide of new money, both British and American. There was a magnificent Louis XV drawing room, a Louis XVI boudoir and English 17th-century panelling in the hall. The Coopers’ luxurious bedroom, however, was in a modern Aesthetic style with white joinery, much in vogue for bedrooms. The house was demolished in 1957.

Most of the plutocrats’ interiors were created by decorators, with furniture and art-works provided by them and by dealers such as Duveen, to create the right kind of mood. A few, including Lord and Lady Brassey, were collectors with specific interests and others developed into serious art collectors. One of the most famous was Sir Julius Wernher, richest of the ‘Randlords’, who made their fortunes in South Africa. Sir Julius bought a late-Georgian mansion, Bath House on Piccadilly, in about 1890. The house was large enough and Sir Julius retained some of its original interiors. He created the Red Room as his study and the setting for his superb collection of Medieval and Renaissance works of art, bronzes, ivories, paintings, enamels and ceramics. Bath House was demolished in 1960, but part of the Wernher Collection remains intact, and is today displayed at Ranger’s House in Blackheath, SE10.

The fortunes of plutocrats were not always what they seemed. José de Murrieta y del Campo, Marqués de Santurce (1834–1915) was a Spanish financier who made a fortune in South America. He and his brother settled in England and entered the Prince of Wales’s circle. He bought No 18, Carlton House Terrace, a huge house that had been remodelled by William Burn for the Duke of Newcastle. The Marqués renovated it, installing electricity. His lift (Fig 4) must have been one of the first to be installed in a London house. However, the de Murrieta brothers suffered heavy losses when the Argentine government defaulted on its bonds and they were obliged to sell up in 1890.

For most of the Victorian and Edwardian super-rich, the years up to the First World War were a golden age. The hordes of servants, the gleaming carriage horses, the liveried footmen and the lavish entertainments in their opulent houses all created an impression of apparently bottomless wealth. There seemed little reason why it should not go on forever, but, in the 20th century, they were overtaken by war, social change, fashion and high taxation. Within a generation, many of the houses had gone and the destruction of so many remarkable interiors seems like a criminal waste. The photographs testify to a way of life and a kind of art which now belong to an unreachably distant past.

'We cannot have beauty without paying for it': The glorious revival of Rochdale's Town Hall

A major restoration project has brought one of Britain's greatest Victorian buildings back to splendour and life. Steven Brindle explains

The extraordinary tale of Hadrian's Wall: 'Men have been deified for trifles compared with this admirable structure'

What once kept out hordes of bloodthirsty warriors is, nearly 2,000 years later, barely proof against the most timid of

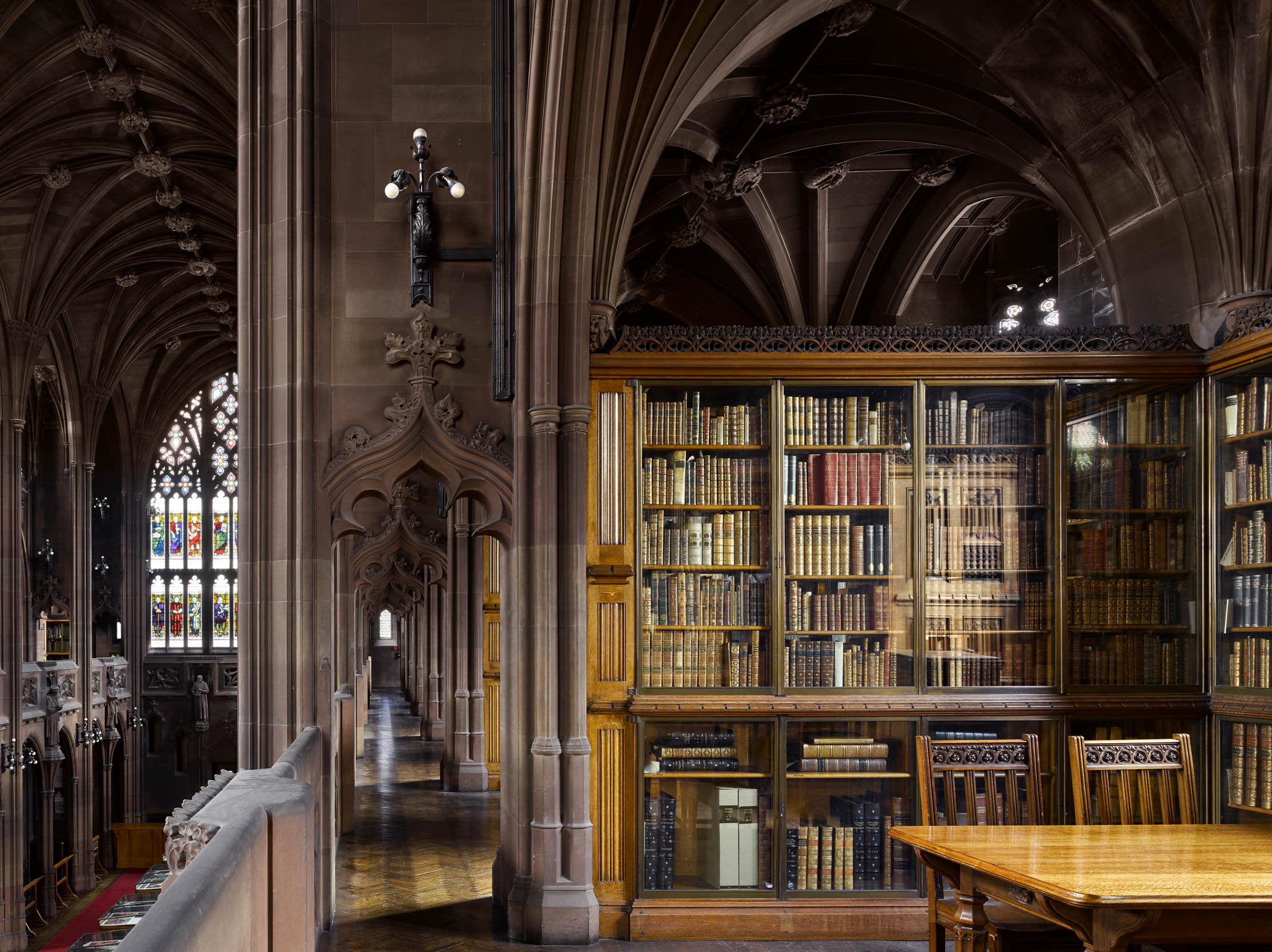

The John Rylands Library: How one of Britain's great libraries was created by a forward-thinking widow

The widow of a successful industrialist turned her inherited fortune towards the creation of one of Britain’s greatest libraries: The

Steven Brindle is an author, historian and holds the title of Inspector of Ancient Monuments at English Heritage.

-

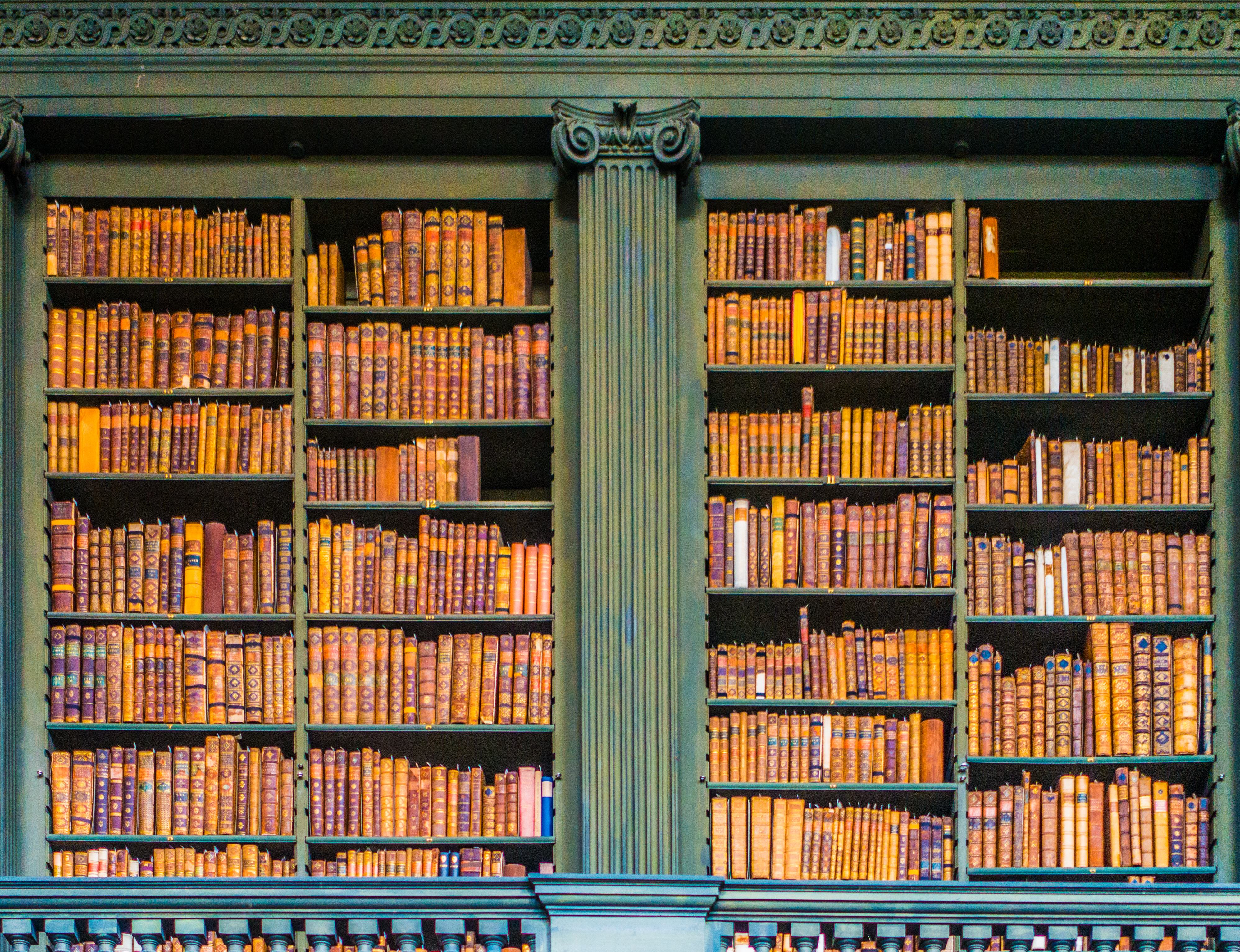

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life