Leighton Hall: The Gothic remodelling of a Georgian house for a Lancashire furniture-making dynasty

A Georgian house remodelled in the Gothic style became a seat of the Gillows family, famous for their furniture-making business, in 1824. John Martin Robinson looks at the remarkable story of the house and its collections. Photographs by Paul Highnam.

Leighton Hall enjoys an astonishing setting. Its sloping, saucer-shaped park, with woods of beech, oak and sycamore, frames views over the estuaries of Morecambe Bay to the Lake District mountains and fells silhouetted in the distance.

It is described in Peter Fleetwood-Hesketh’s Murray’s Lancashire Architectural Guide as ‘a picture of magic beauty, with the distant fairyland of Furness beyond’.

The whole scene is the very quintessence of English Picturesque taste, with the early-19th-century castellated façade, built of finely dressed white limestone, looking like an opera set against the sublime landscape backdrop. When the sun shines and the white stone gleams, it seems a barely credible vision. This remarkable house has been the seat of the Gillow family, descended from the famous furniture manufacturers, since 1824.

Leighton is essentially a Georgian house on an older site, re-fronted in the 1820s to give it a gothic air. The architect for the Regency re-fronting is not known, but the work has been attributed to Thomas Harrison of Chester or Joseph Gandy, who worked at Lancaster Castle, where the architecture shows similar characteristics.

There is no evidence, however, for any involvement by Harrison and it is more likely that the re-facing was by the local Lancashire architect Robert Roper of Preston, on the strength of comparison with Roper’s similar Gothic re-fronting in 1823 of Thurnham Hall, south of Lancaster, for the Daltons, fellow Catholics, friends and neighbours.

Robert Roper was a Catholic too, much employed by the recusant gentry of Lancashire in the early 19th century, rebuilding Leagram Hall (since replaced) in 1822 for George Weld, and Claughton Hall (also replaced) in 1816 for the Fitzherbert-Brockholes family. He was also responsible for the pre-Emancipation Catholic church of St. Mary at Fernyhalgh, near Preston, where the Revd Richard Gillow later became the incumbent in 1823. Roper, therefore, would have been well-known both to the Gillows and to their cousins and the previous owners of Leighton, the Worswicks, bankers in Lancaster.

The exact date of the Regency reconstruction of Leighton is a mystery. It could pre-date the Gillow acquisition of the estate and have been undertaken by Thomas Worswick Jnr, who owned Leighton from 1805-1823. In the latter year, the Worswick bank in Lancaster failed and the executors sold Leighton to Thomas’s cousin, Richard Gillow II. If Worswick was responsible for the reconstruction, it would explain the lack of any building documentation in the Gillow family archive.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It seems most likely that Worswick reconstructed Leighton in about 1820 and that Richard Gillow bought the house when newly completed in 1824. This would explain the substantial amount he paid for the 2,000-acre estate, which was then mainly rocky pastoral land.

Leighton Moss, north of the house, was only drained for ‘improved agriculture’ by Richard Gillow after the purchase, using steam technology, but this briefly productive land reverted to swampy reed beds after the agricultural depression in the late 19th century, and is now an important RSPB nature reserve.

Leighton is T-shaped and incorporates part of an old house of uncertain date but probably built by its 17th-century owners, the Middletons, Royalist baronets. It passed through the female line to Albert Hodgson, an unfortunate Jacobite who was taken prisoner at Preston in 1715. Leighton was thereafter confiscated and sold, but Hodgson was able to return to it because it was bought on his behalf by a friend and lawyer, Mr. Winkley of Preston.

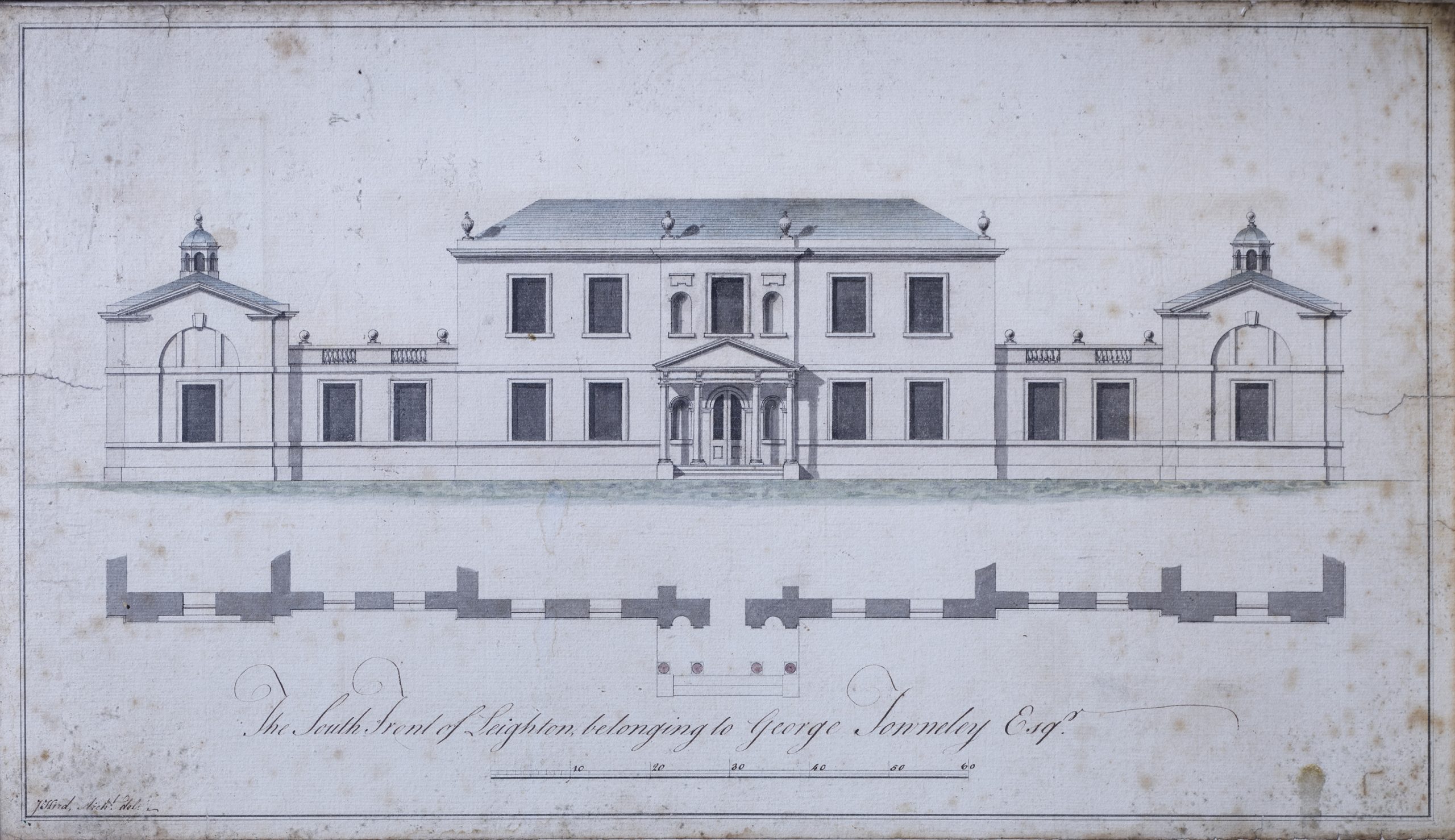

Hodgson's daughter, Mary ,married George Towneley, a cadet of the Towneley family of Towneley. The couple built the Georgian nucleus of the present house and landscaped the park in 1759-61. A preliminary design still hangs in the hall, showing an elaborate, if old-fashioned, Palladian design comprising a main block and wings influenced by James Paine. This drawing is signed by John Hird, a carpenter-pupil of Carr of York, active in north Lancashire and Kendal in the mid-18th century; Hird was responsible at the time for Gothicising Sizergh Castle for Cecilia Towneley, wife of Thomas Strickland.

Hird’s hand is attested by surviving details, such as hefty architraves in some of the un-Gothicised bedrooms, and his plain rear elevation survives. Hird’s composition, originally with a five-bay, pedimented centre, underlies the present house. A later proposal to rebuild the wings in a neo-Classical manner with Wyattesque tripartite windows, possibly by Webster of Kendal, was not executed.

Roper’s 1820s scheme for remodelling involved the cosmetic addition of battlements, turrets, Gothic windows and a projecting front porch to the Palladian house. The west pavilion is treated as a ‘chapel’ with a large, blank Gothic window and a little stone cross on the gable. This is purely scenic and screens the end of the symmetrical, pedimented Georgian stables, which are similar to Hird’s at Bigland near Cartmel.

The west pavilion was treated as a ‘tower’, giving the elevation a mild asymmetry, but the composition was hugely improved in 1870 when Richard Gillow III commissioned Paley & Austin to replace the Georgian tower with a more assertive three-storeyed structure. The Victorian tower contained a new billiard room (now music room) on the ground floor with guest rooms above. The old billiard room in the west wing was converted to a dining room at that time. The new tower is the major Gillow contribution to the architecture of Leighton.

The Gillows were descended from a family of Catholic yeomen in the Fylde of Lancashire. Their history is expounded in Susan Stuart’s excellent book on Gillows furniture Gillows of Lancaster and London, 1730– 1840 (Antique Book Club, 2008). Robert Gillow I (1702–72), whose father died young after being imprisoned for harbouring a priest —his wife’s brother—moved from the farm in the Fylde to Lancaster and established there the famous furniture business, after apprenticeship to John Robinson, a Catholic joiner.

He established the Gillows firm in Lancaster in 1730, at about the same time that the tax on imported mahogany into Britain from the West Indies was abolished. Lancaster, as an Atlantic seaport, became a centre for making mahogany furniture, which benefitted the Gillows and other energetic and talented entrepreneurs in the town.

The Gillows firm flourished over three generations and became one of the largest and most successful furniture businesses in England, with fashionable premises in Oxford Street, London, for which the architect James Wyatt supplied sophisticated neo-Classical furniture designs in the 1770s and 1780s, as well as the workshop in Lancaster. Robert’s eldest son, Richard Gillow I, trained as an architect in London and designed the Palladian Customs House in Lancaster in 1768, on top of being a cabinet maker. He and his brother continued and expanded the business in Lancaster and London.

Robert’s daughter, Alice, married Thomas Worswick Snr, a Catholic banker in Lancaster, and a younger son, John (1753-1728), was educated at Douai, and became a priest and professor of theology there, returning home in 1791 during the French Revolution and becoming president of Ushaw College, Co Durham.

As the firm’s wealth and success increased, so the family rose in social status—the three sons of Richard I all married into the old Catholic families. After the sale of the firm for more than £50,000 in 1813, the Gillows established themselves as landed gentry in their own right. Robert Gillow III bought Clifton Hill at Forton in Lancashire and built a new house there to his own design in 1820.

George, the middle son, had a house at Hammersmith and formed a collection of Old Master paintings, some of which once belonged to Reynolds. George died in 1811 leaving eight daughters. Some of his collection had been sold already by Christie’s, but those paintings that did not sell were bought by the youngest brother, Richard Gillow II, for his new country house at Leighton, where they still hang.

Richard Gillow II, the founder of the Leighton family, married Elizabeth Stapleton, niece of Nicholas Stapleton of Carlton Hall (later Towers) in Yorkshire. They lived at first in Little Holland House, Campden Hill, Kensington, West London, and rented Ellel Grange, next to Clifton Hill, and Thurnham Hall in Lancashire. In April 1824, the family moved from Ellel to its own new seat at Leighton, having purchased the estate for £23,000. Richard Gillow II died in 1849 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Richard Gillow III, who married Agnes Eyston of East Hendred, a descendant of Thomas More.

Richard Gillow III built the Catholic church in the adjoining village of Yenland Conyers to the design of E.G. Paley in 1852. Pevsner described it as ‘outdoing the Anglican church in size, prominence and quality’. He used the same architectural firm for his improvements to Leighton in 1870. He survived his son and eventually died in 1905 at the age of 99, after falling from his horse while riding with the Vale of Lune Hunt.

By that time, Leighton had become somewhat dilapidated and run down. Following the death of the grandson, Charles Richard, in 1923, the place was let for a time as a school, but heiress Helen Gillow married James Reynolds, of the great Liverpool cotton broking house Reynolds & Gibson, in 1931, and they moved back in with Helen’s widowed mother.

The Reynolds connection helped to revive Leighton. Both James and his eldest son, another Richard, worked for the firm, although, after the 1950s, the Lancashire cotton industry shrank in the face of cheaper Asian imports and the cotton plantations in Egypt were nationalised and expropriated by Nasser at the same time as the Suez Crisis. Helen and James Reynolds modernised and redecorated the house; the rooms survive today much as they arranged them in the post-war period.

The entrance is through a porch with 1820s painted glass of Faith, Hope and Charity over the door in the style of Eginton of Birmingham. A Gothic screen divides the hall interior beyond from the staircase. Simple Gothic chimneypieces were inserted in the library and drawing room, which otherwise retained plain moulded, plaster cornices.

The principal Regency Gothic interior is the dining room, originally the billiard room, with an oval skylight in the centre of the ceiling and thin ribbed plasterwork. The Gillows were famous for their billiard tables, which they had started manufacturing in the 1770s. Here, the room is lined with wooden panelling framing inset Italian 18th-century landscape paintings, recalling the real views outside the windows. The Georgian dining chairs made of walnut with back splats are one of the earliest sets made by Robert Gillow in about 1730. There are also two fascinating 17th-century carved oak Lancashire arm chairs, one given by R.F. Bradshaw and the other by the historian Dr John Lingard, the priest at Hornby.

As to be expected, there is much Gillows furniture in the house, forming a cross-section of the firm’s production over the three generations of family ownership. Some of the best pieces are in the drawing room, where the walls are hung with the collection of Dutch, Flemish and Italian paintings formed by George Gillow. These are of uneven quality and some are copies but they are nonetheless interesting as a group and a little-known survivor of a small late-Georgian collection.

Today, Leighton is lived in by two generations of the family: Suzie, widow of the late Richard Gillow Reynolds, and their daughter, Lucy, and her family, who occupy the east part. They have developed a business to maintain the property, opening the house to the public and hosting events.

The walled garden has been revived and replanted, and a grass maze has been laid out under the fruit trees in the old orchard. The place maintains the cosy atmosphere of a family home, as Leighton looks forward to its 200th anniversary of Gillows ownership.

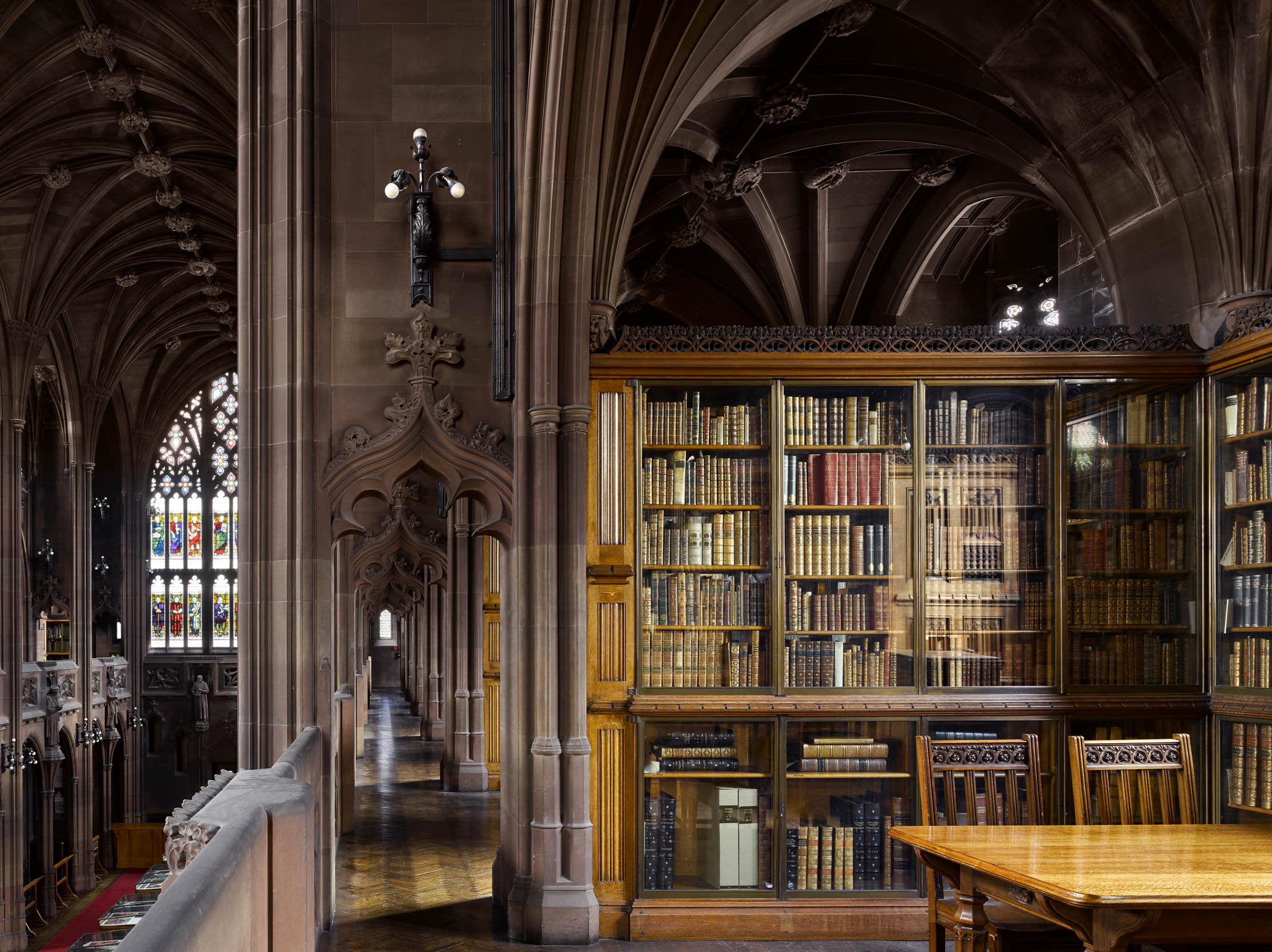

The John Rylands Library: How one of Britain's great libraries was created by a forward-thinking widow

The widow of a successful industrialist turned her inherited fortune towards the creation of one of Britain’s greatest libraries: The

-

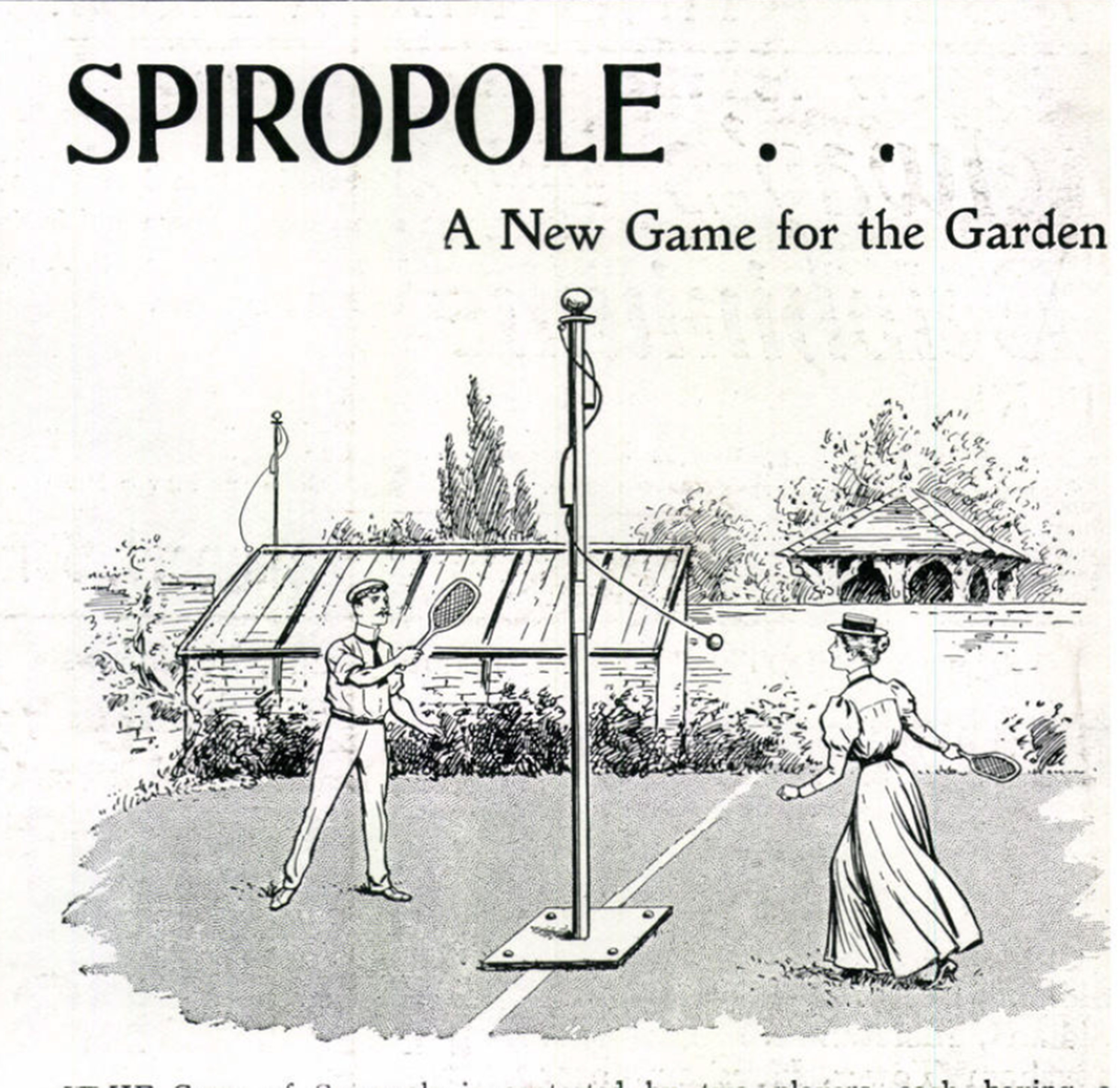

From the Country Life archive: The 19th century answer to Swingball

From the Country Life archive: The 19th century answer to SwingballEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

Hope from the ashes: A new generation of ash trees is evolving to make them more resistant to dieback

Hope from the ashes: A new generation of ash trees is evolving to make them more resistant to diebackWhen ash dieback first arrived in Britain, in 2012, an emergency COBRA meeting was formed. The disease has since spread rampantly across the countryside, but there is still hope.