Inside Windsor Castle, by kind permission of the Sovereign

As the new reign begins, John Martin Robinson takes an exclusive look at Windsor Castle, Berkshire — an official residence of His Majesty King Charles III — and in particular the recently completed representation of the State Apartments. Photographs taken in the last few days of the reign of the late Queen Elizabeth II by Paul Highnam for the Country Life Picture Library.

The State Apartments in the Upper Ward at Windsor Castle occupy the shell of a palace constructed in the 14th century by Edward III. These interiors have been repeatedly reworked on the most opulent scale by a succession of monarchs (Fig 2), with particularly notable changes undertaken by the architect Hugh May for Charles II in the 1670s; by James Wyatt for George III in the 1790s; by Jeffry Wyatville for George IV from 1824 and by Anthony Salvin for Prince Albert and Queen Victoria.

More recently, the disastrous fire in November 1992 prompted a massive programme of rebuilding and restoration. It was in the course of these works that the then director of the Royal Collection from 1996 to 2010, Sir Hugh Roberts, first conceived the idea for upgrading the surviving historic State Apartments in the building with a view to enhancing their appearance and modernising visitor facilities.

This Future Programme of improvements — as this project came to be described — was formally announced in April 2016. Sir Jonathan Marsden, who succeeded as director in 2010, organised special sessions with heritage professionals to discuss the proposals and develop them. They were planned in tandem with a similar programme at Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh. Work at both palaces started in 2017, shortly before Tim Knox took over as director of the Royal Collection in March 2018. They then proceeded under his direction until their completion in mid 2020, amid the covid lockdowns. The project has been almost entirely self-funded by the Royal Collection Trust (RCT), on which the pandemic had a dramatic financial impact.

The architects for the Windsor scheme, which involved delicate archaeological consideration of such an important and complex historic site, were Purcell and the lead appointed to supervise it was Moira Gemmill, former director of design at the V&A Museum. Tragically, she was killed in a bicycling accident just before the project was launched. Tot Brill, who succeeded her, also died unexpectedly, in 2019, and the scheme was seen to completion by Alex Attelsey of the Royal Household Property Section. A Future Programme Project Board, chaired by former RCT trustee Peter Troughton, monitored progress and made many helpful suggestions.

All the work was approved by the late Queen and the then Prince of Wales, now The King, who was responsible for retaining the interior designer Piers von Westenholz as an adviser. The Baron von Westenholz contributed many important suggestions for the finishes and presentation of the rooms, assisted by Simon Hurst, a young architect trained in The Prince’s School of Architecture. Their — and The King’s — concern for historical detail and artist’s eye for colour, tone and texture have enhanced immeasurably the refurbished rooms and the recent works make the State Apartments fully accessible.

The visitor entrance to the State Apartments used to lead from the North Terrace through an incoherent sequence of constricted spaces to one side of the Grand Stairs. Today, the same entrance opens instead into the reconstituted Inner Hall, which has been put back as far as possible to the original Wyatt design and enhanced by dramatic lighting and new Gothic lanterns. This is a spectacular late-Georgian interior, with stucco lierne vaults studded with foliate bosses and Gothic columns moulded by Francis Bernasconi, which was enlarged by Wyatville for George IV. It now creates a breathtaking north-south vista through the lower floor of the castle’s range (Fig 3), a view that had been blocked since 1866 by the erection of a masonry wall.

The vista in both directions is splendid. To the north, there is a view over the North Terrace far into Buckinghamshire, across Eton College. To the south is a glimpse of one of the grandest historic landscapes in England, through the State Entrance, Upper Ward and George IV Gate, down Charles II’s Long Walk, terminating nearly three miles away in the silhouette of Sir Francis Chantrey’s bronze monument to George III high on a craggy, granite plinth (Fig 5). Long referred to as the ‘Copper Horse’, an unfortunate guest was rebuked for such a solecism by Queen Victoria, who asked: ‘Do you mean the equestrian statue of Our Grandfather?’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

From the Inner Hall, the visitor can now progress to the State Entrance — open to the public for the first time — and onto the Grand Stairs. In both areas, the armour displays have been cleaned and rearranged (Fig 4). In the former, there are trophies of serried arms on the walls above and glazed Gothic oak cases below to show the finest armours. Particularly notable are the productions of the Tudor workshops at Greenwich and the tiny damascened suits made for Prince Henry, the elder brother of Charles I, who died young. Some of the cases are Victorian and some newly made to match.

The tall timber lantern and hanging glass chandelier over Salvin’s magnificent Grand Staircase (Fig 7) have both been repaired by the Royal Household’s Property Section, with a new central boss, carved with an ER-II monogram. Immediately striking is the new stair carpet devised by the Baron von Westenholz and Mr Hurst. The ubiquitous royal crimson has been replaced with dark green, the Windsor estate livery colour, patterned with heraldic crosses pattées. It extends from the stairs through the Grand Vestibule to the Guard Chamber, on the piano nobile. A new carpet has also been made for the Grand Reception Room, copying one designed by Prince Albert, replicated from an old photograph (Fig 8).

In the Grand Vestibule at the head of the stairs, the Gothic cabinets installed for the display of gifts presented to Queen Victoria on her Diamond Jubilee have been redisplayed, with an astonishing array of artefacts from all over the world. Each case is devoted to a separate continent and the objects range from trophies obtained by force of arms at Seringapatam to a scarf given to Elizabeth II by Nelson Mandela. These displays replace a rather incoherent jumble of Imperial relics and weaponry; visitors greatly enjoy spotting things from their own countries of origin.

The main focus of the redecoration, however, has been in the Charles II State Rooms, which were originally designed by the gentleman-architect Hugh May, a protégé of Wren, in 1675–78, partly within the shell of Edward III’s medieval palace and partly in a large new rectangular block facing north called the Star Building. May employed the Italian artist Antonio Verrio to paint the ceilings with mythologies, the Order of the Garter and naturalistic trompe-l’oeil decoration. The carver Grinling Gibbons also owed his first significant commission to May at Windsor and, together, they created here the unique English formula for the Baroque interior with Italian painted ceilings and Anglo-Dutch carved wainscot of astonishing virtuosity. The Windsor interiors formed the model for the noble state rooms at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, Burghley in Lincolnshire, Boughton in Northamptonshire and Petworth in West Sussex.

The layout at Windsor represented in its most extended form the apartments necessary for Court life and royal ceremonial. As was the norm in English and French royal palaces — at least since the 13th century (and first unambiguously documented in the reign of Henry III) — there were separate apartments for the King and Queen. Both assumed a common layout, which was, in practice, defined by those of the King. These were organised in order to regulate and formalise contact with the Sovereign, with rooms opening off each other in strict sequence. By this arrangement, it was possible to withdraw from relatively public outer rooms into more retired — and private — spaces. Over time, the number of rooms gradually multiplied.

By the 16th century, the King’s apartment comprised a Guard Room for the Yeoman of the Guard, the Presence Chamber for ‘Lords, Knights, Gentlemen and officers of the King’s House’, the Privy Chamber or Audience Chamber for those invited by the King, the Bedchamber where only the King’s inner household servants were permitted, followed by the King’s private rooms, the dressing room and closet. Eventually, the Privy Chamber became an assembly room for the Court. Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria, therefore, inserted a more select drawing room between it and the bedroom. This was the plan followed by Charles II at Windsor and, in due course, by Queen Mary and William III in Wren’s state rooms at Hampton Court, which overtook Windsor as the principal country palace of the English Crown up to the death of George II.

The early Hanoverians avoided Windsor, which was regarded by them as a monument to the Stuarts, and the State Rooms remained undisturbed until George III moved back into the castle in the 1790s. His return reflected a revival of interest in the English constitutional tradition in reaction to the French Revolution. George III revived the State Apartments for Garter ceremonies and formal royal festivities, with an admirably conservative architectural approach. He retained the Verrio ceilings, oak dados and carved acanthus-leaf cornices, but replaced the dark wainscot on the walls with rich hangings of Garter blue velvet, red silk damask and floral needlework borders, as a background for paintings from the Royal Collection, including new commissions from Benjamin West. The striking results are recorded in the aquatints Pyne’s Royal Residences (1819), for which the original watercolours survive in the Royal Library at Windsor.

George IV, with his architect Wyatville, concentrated on creating new semi-state and private apartments in the south and east ranges of the Upper Ward and reconstructing St George’s Hall, in tandem with the heroic reconstruction of the palace exterior as a dream Gothic castle between 1824 and 1830 at a cost of more than £1 million (Fig 1). The renovation of the State Rooms only took place after the King’s death in 1830 and to a tighter budget than the government had been able to inflict on that profligate monarch, but still using the competent Wyatville as architect (whereas Nash was sacked at Buckingham Palace).

Sadly, all but three of Verrio’s ceilings, which it was doubtfully claimed were structurally unsound, were replaced with heavy white and gold stucco designs. These sport fleshy naturalistic scrollwork, Stuart and Hanoverian heraldry, Garter insignia and the monograms of William IV and Queen Adelaide, all the work of Francis Bernasconi, the leading Wyatt stuccadore with an almost industrial production line.

These were essentially cosmetic changes, however, and the layout and character of the rooms substantially survived. An exception was the Queen’s Bedchamber, which was transformed into the new Royal Library, installed at Windsor by William IV. George IV also truncated the King’s apartment by converting the King’s Guard Chamber into the Grand Reception Room — detailed in dazzling French Rococo style (Fig 10) — and the Privy and Presence Chambers to the Garter Throne and Ante Rooms.

Under Queen Victoria, the State Rooms were used for royal visits, notably that of Napoleon III in 1855, when George IV’s magnificent gilt bed by Georges Jacob was rehung in Napoleonic green and purple and placed in the King’s Bedchamber. The principal input was Prince Albert’s, who repurposed the rooms for the display of paintings collected by the Stuarts, Frederick Prince of Wales, George III and George IV.

Assisted by Richard Redgrave, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, the paintings by Rubens were concentrated in the King’s Drawing Room, the van Dycks in the Queen’s Gallery and the earlier paintings, notably the Holbeins, in the Queen’s Drawing Room (Fig 12). To reflect this, the rooms were respectively renamed the Rubens Room, Van Dyck Room and Picture Gallery.

The hang reflected the Prince’s pioneering art-historical scholarship and his and the Queen’s interest in the educational possibilities of art, allowing access to the collections and lending to public exhibitions. The Carolean State Apartments were happily untouched by the 1992 fire and were relatively unaltered in the 20th century, apart from some characteristically judicious improvements by Queen Mary who, for instance, restored the 17th-century oak wainscot in the Garter Throne Room and King’s Dining Room in the 1920s and rearranged the furniture.

The recent work respects the many historic layers of these rooms and has involved Royal Collection curators enhancing and extending the picture hangs in the spirit of the Prince Consort, as well as commissioning a series of magnificent new carpets. These latter were designed for the individual rooms by Mr Hurst, with advice from Mr von Westenholz, and their weaving organised by Brinton Carpets in Kidderminster. These carpets take their cue from Wyatville and Bernasconi’s ceilings, with geometrical patterns enriched with fasces and similar classical details or floral swags and scrolls.

In the Queen’s Presence Chamber and Audience Chamber — which retain their Verrio ceilings celebrating the apotheosis of Catherine of Braganza — the new carpets have a diaper pattern and borders derived from those in the Gobelins ‘History of Esther’ tapestries on the walls.

In the Queen’s Gallery (the Van Dyck Room) the new carpet echoes Wyatville’s geometrical ceiling design in blue and silver to go with the blue damask on the walls and the Charles II silver furniture (Fig 13). The array of van Dyck portraits has been immeasurably enhanced by bringing the two huge portraits of Charles I — The Great Peece and The King on Horseback with M. de St. Antoine from Buckingham Palace, which are now hung on the end walls, repeating the original intention in the Gallery at Whitehall Palace.

In the Queen’s Drawing Room, the new carpet repeats the ceiling pattern in very rich colours, countering the slightly anaemic white and gold of the plasterwork above. The old hang of Tudor and Stuart portraits here is augmented by a new acquisition, a portrait by Gerrit van Honthorst of the Electress Sophia — the ‘missing link’ between the Stuarts and the Hanoverians — bought in 2018.

The ‘Three Kings’ — the King’s Closet, the King’s Dressing Room and the King’s Bedchamber — all crimson damask hung, have been further unified by a continuous drugget designed by Mr Hurst in a splendid combination of purple, green and gold. A new picture hang in these rooms continues and respects the thematic hangs originally conceived by Prince Albert, all set off against rich crimson damask. The King’s Closet is now a ‘cabinet’ of Northern European Old Masters, including works by Breughel, Holbein and Cranach, as well as early portraits of English monarchs (Fig 11).

The King’s Dressing Room is now shown as a complementary ‘cabinet’ of Italian Old Masters, with masterpieces by Bellini, Bronzino and Carracci, representative of classic English connoisseurship (Fig 14). In the King’s Bedchamber, the picture hang is still in progress, but it will eventually evoke Charles I’s collection, the foundation nucleus of the Royal Collection, in a dense, tiered hang.

In the King’s Drawing Room (Fig 9), the Rubens canvases in carved frames made for Frederick, Prince of Wales hang in their historic position, complemented by the most splendid of Mr Hurst’s carpets. This replaces a faded Persian rug and transforms the room. These changes have been accompanied by the rethinking of visitor movement through the interiors, allowing for the removal of unnecessary druggets and a reduction of ropes and stanchions. New lavatories and disabled access were also planned, as the rooms are used for royal ceremonial throughout the year, as well as tourism. The attention to detail here extends to the crenellated oak cubicles and fossil marble basin surrounds.

The Undercroft Café (Fig 6) is another major addition to the visitor facilities. Although Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire and Longleat in Wiltshire had led the way in providing such visitor amenities as long ago as the 1950s, there had been no comparable provision for refreshments at Windsor. Now, the opportunity has been taken to convert Edward III’s spectacular vaulted wine cellar — the undercroft of St George’s Hall — into a café. The shell of the space was stripped after water damage in the 1992 fire, leaving the varied colours and ancient battered surface of the stonework. The Baron von Westenholz advised on this informed authentic approach. The medieval floor level was restored by the painstaking removal of a deep raft of in-filling concrete. The new oak furniture in the Undercroft Café is all in the Gothic style, of course, and was made in the workshops of Character Joinery in Kilmarnock, which has worked on The King’s Dumfries House estate in Ayrshire.

The Future Programme has also included changes to the visitor facilities at the tourist entrance in St Alban’s Street to the south of the castle. There, the welcome area in the former Lord Chamberlain’s workshops has been tactfully expanded and enhanced, using the stock brick characteristic of the utilitarian buildings of the Office of Works. An access ramp has been provided to relieve queueing on the street and a separate entrance contrived for schoolchildren, who will use the Learning Centre established in next-door Pug Yard (called after the mortar-process, not the dog), built and equipped with generous grants from the Clore Duffield and Wolfson Foundations. As well as schoolchildren, the Learning Centre is used by wider community groups and its interior has been amusingly furnished with props salvaged from the 2012 Diamond Jubilee Barge, including Royal Arms, jolly heraldic animals and giant thrones.

As re-presented to the public, the interiors of Windsor Castle at the beginning of the new reign have a renewed magnificence and architectural coherence. They are also better served in a practical sense than ever before. The greatest and most historic of English royal palaces can now be enjoyed even more as one of the finest surviving ensembles of its type in the world and a place of which the British nation can be rightly proud.

For further information, visit www.rct.uk/visit/windsor-castle. Additional picture credits: Royal Collection Trust/©His Majesty King Charles III 2023

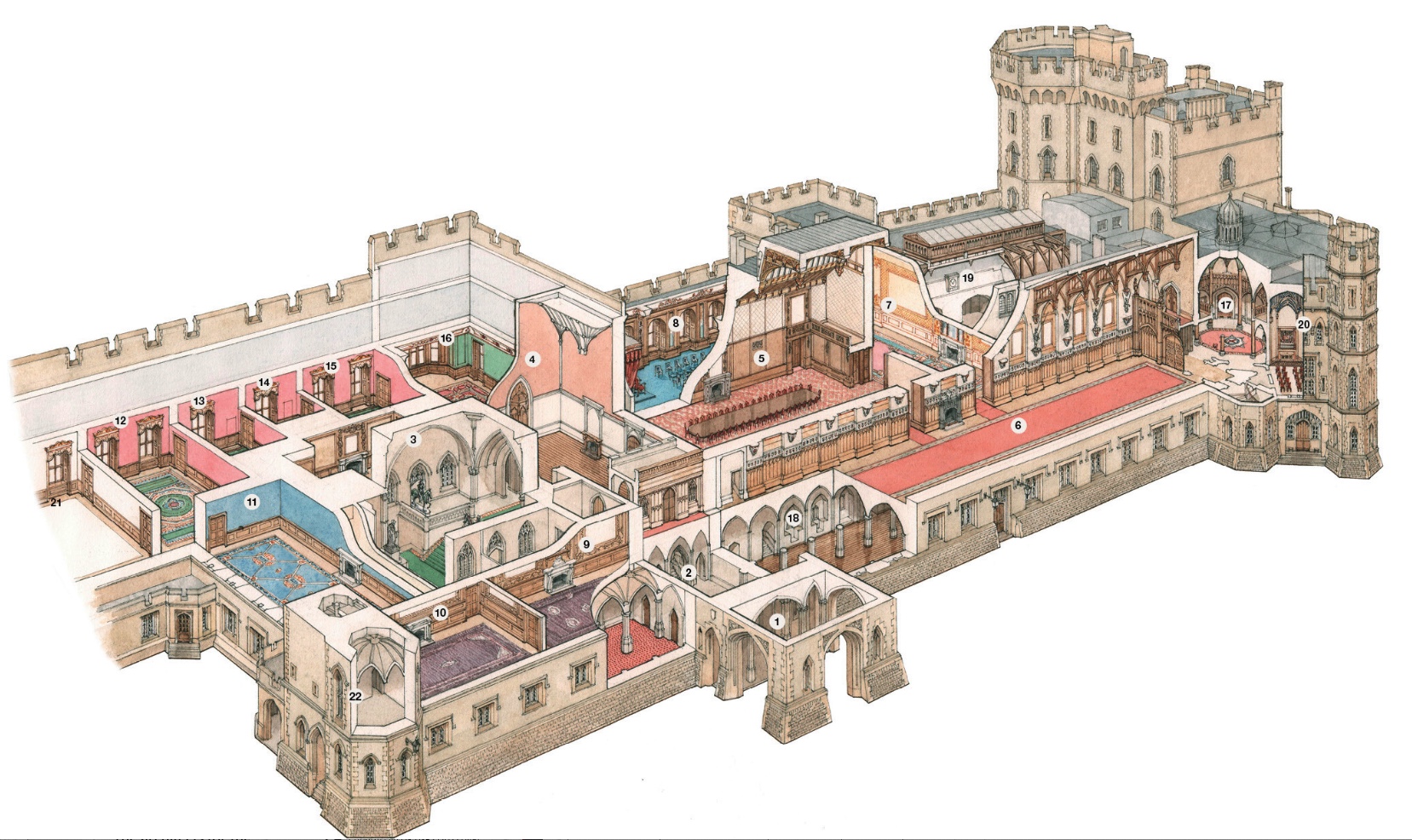

The layout inside Windsor Castle

1. State Entrance 2. Hall and Inner Hall 3. Grand Stairs 4. Grand Vestibule 5. Waterloo Chamber 6. St George’s Hall 7. Grand Reception Room 8. Garter Throne Room 9. Queen’s Presence Chamber 10. Queen’s Audience Chamber 11. Queen’s Gallery (or Van Dyck Room) 12. Queen’s Drawing Room (or Picture Gallery) 13. King’s Closet 14. King’s Dressing Room 15. King’s Bedchamber 16. King’s Drawing Room (or Rubens Room) 17. Lantern Lobby 18. Undercroft 19. Great Kitchen (not on the public visitor route) 20. Private Chapel (not on the public visitor route) 21. Royal Library (not on the public visitor route) 22. The 14th-century private stair to the Royal Chambers, in the Rose Tower (not on the public visitor route)

News of the Black Prince’s victory at Poitiers and the capture of the French King, John II, on September 19, 1356, prompted Edward III to embark on the construction of a vast new palace in the Upper Ward of Windsor Castle. It was laid out around three courtyards set behind a massive frontage that comprised the three principal interiors of the palace — the King’s Chapel, hall and chamber — set end to end. It is within the shell of this building, and behind its great façade, that the present royal apartments have developed ever since.

Particularly important have been the changes undertaken for Charles II in the 1670s; George III in the 1790s; George IV from 1824; Prince Albert and Queen Victoria in the 1850s; and Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh after the fire of 1992. Edward III had been engaged in building works in the castle since his Arthurian celebrations there in 1346, from which emerged the royal chivalric brotherhood of the Order of the Garter. With the chapel of the Order, dedicated to St George, in the Lower Ward of the castle, this vast residence in the Upper Ward and the amenity of the surrounding parkland, Windsor henceforth became the unquestioned principal seat of the Kings and Queens of England.

Country Life's architectural editor John Goodall and our illustrious contributing writers discuss Britain's greatest architecture in the magazine every week. Find out how to subscribe to the magazine here.

The great architect Donald Insall on saving Windsor Castle, refurbishing Westminster and how buildings change throughout their lives

The Queen's official Platinum Jubilee portrait unveiled, taken by Ranald Mackechnie at Windsor Castle

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II's official Platinum Jubilee portrait photograph has been unveiled.

HRH the Duke and Duchess of Sussex show off baby Archie in photoshoot at Windsor Castle

HRH Prince Harry and the Duchess of Sussex proudly showed off their baby boy to the world on Wednesday.

-

'The city has always held an important creative space within our design studio': A luxury townhouse in Tokyo, courtesy of Aston Martin

'The city has always held an important creative space within our design studio': A luxury townhouse in Tokyo, courtesy of Aston MartinA new four-storey property in the Omotesandō district is the first single home private residence by the British ultra-luxury performance brand.

-

Tuning in with the past: Monk music will ring out for the first time since the Dissolution after medieval manuscript is rediscovered

Tuning in with the past: Monk music will ring out for the first time since the Dissolution after medieval manuscript is rediscoveredBuckland Abbey once thronged with monks who sang for hours every day. Now, some of their newly rediscovered medieval music will ring out once more.

-

Ironmongers' Hall: The medieval marvel destroyed by a First World War bomb, and it's inspiring 21st century renaissance

Ironmongers' Hall: The medieval marvel destroyed by a First World War bomb, and it's inspiring 21st century renaissanceIronmongers’ Hall in London EC2 — home of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers — is one of the Great Twelve City Livery Companies. This year it is celebrating the centenary of its Tudor-style Hall; John Goodall takes a look, and tells the remarkable story of the building. Photographs by Will Pryce for the Country Life Picture Library

-

50 years ago, the English country house seemed headed for extinction. Instead it was the start of a new golden age

50 years ago, the English country house seemed headed for extinction. Instead it was the start of a new golden ageRather than perceiving the mid 20th century as a troubled period in the history of the country house, John Martin Robinson argues that it was perhaps one of the most interesting, unexpected and enterprising. All photography from the Country Life Image Archive, by June Buck, Paul Barker, Val Corbett, Will Pryce and Paul Highnam.

-

‘It has been destroyed beyond repair, not by the effect of gunfire, but by a deliberate act of vandalism’: Britain’s long lost great houses that live on only inside the Country Life archive

‘It has been destroyed beyond repair, not by the effect of gunfire, but by a deliberate act of vandalism’: Britain’s long lost great houses that live on only inside the Country Life archiveIn the wake of the First and Second World Wars, some of Britain’s greatest houses were lost forever — to extinct familial lines, financial woes, neglect, vandalism and tragic accidents. Thankfully, plenty are preserved — in photographic form at least — for eternity, inside the Country Life archive.

-

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of life

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of lifeThe historic buildings of a Transylvanian settlement have been restored and preserved with the help of several foundations and backed by The King’s personal enthusiasm. Jeremy Musson reports on this remarkable place; photographs by Paul Highnam.

-

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South Bank

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South BankEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home where she penned her final words and drew her final breath

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home where she penned her final words and drew her final breathJane Austen spent the last days of her life in rented lodgings in Winchester, Hampshire. Adam Rattray describes the remarkable recent discoveries made about the house in which she died.

-

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to live

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to liveKings, cobbles, secrets, superstition and literary fire power–Winchester has had it all in spades for centuries and is as desirable now as it ever was, says Jason Goodwin.

-

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up above

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up aboveA series of new plasterwork ceilings, collaboratively designed with the creating artist, has transformed the interiors of The Old House, Dorset, the home of Charles and Jane Montanaro. Jeremy Musson explains more; photographs by Paul Highnam.