‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

A romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

One hundred years ago, an architect named Clough Williams-Ellis went to view an overgrown private peninsula on a wide estuary near Snowdonia (now Eryri), North Wales. The site had been badly neglected. Staring up and around, he saw a deserted mansion on the shoreline, a weed-choked stable block on the hill and gnarled cliffs poking above the trees. As his eyes met each feature, his heart soared. He’d scoured the British Isles for a setting such as this and, finally, here it was on the Welsh coastline. A place to build his village.

For decades, Williams-Ellis had harboured a wish to create a township that would be in harmony with the landscape around it, accentuating rather than spoiling the natural scenery. This half-hidden headland was the perfect spot. ‘When I saw it,’ he later remembered, ‘I thought, gosh, I need look no further.’ Within days, he had contacted the Midland Bank to arrange a loan to buy the peninsula, soon changing its name from Aber Iâ (Glacial River Mouth) to Portmeirion, a title that combined the site’s coastal location with Merioneth, the historic county in which it sat.

Portmeirion's myriad styles include Arts-and-Crafts-style cottages, Palladian houses, a Gothic pavilion and even an Italianate bell tower.

The purchase took place in 1925. By the Easter weekend of 1926, he was already able to welcome visitors. The run-down mansion — the previous tenant of which had been a recluse, fond of reciting Bible verse to her 15 dogs — had morphed into Hotel Portmeirion. This was merely the start. Over the next 50 years, Williams-Ellis turned Portmeirion into a kind of piecemeal romantic experiment, essentially willing an entire village into being. Gardens were set out, pathways were laid and buildings of myriad styles were erected and embellished: Arts-and-Crafts-style cottages, Palladian houses, a Gothic pavilion and even an Italianate bell tower. Some of the structures were crafted on site, whereas others were salvaged from elsewhere and moved there at considerable effort.

He was obsessed with the joy that could be found through architecture and aesthetics, embracing anything that felt right, anything that could be beautified or ‘Clough-ed up’. The resulting settlement, dotted with statues, filigreed with adornments and surrounded by the mountainous natural majesty of North Wales, remains unlike any other.

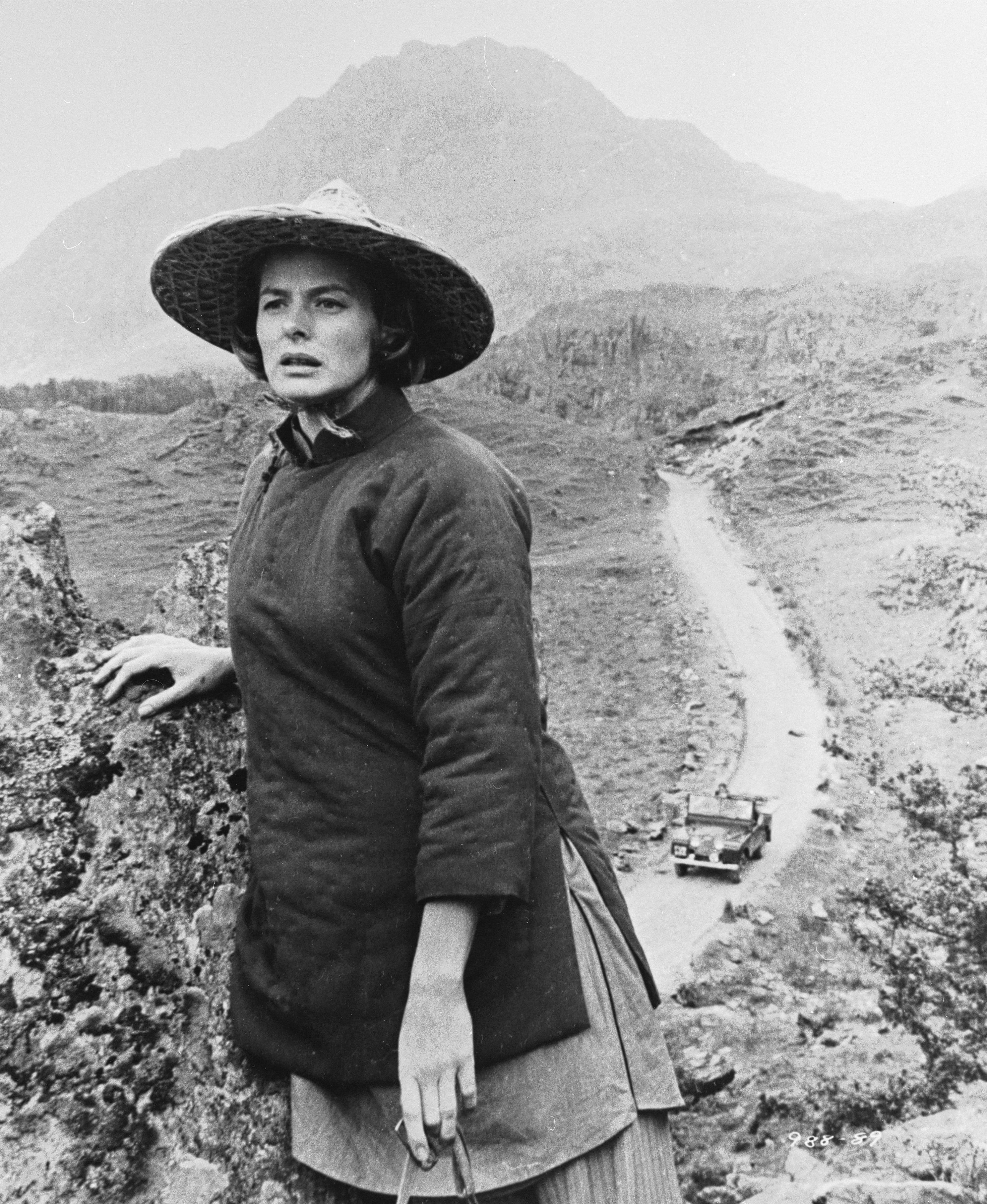

'The Inn of the Sixth Happiness', starring Ingrid Bergman was partly shot in North Wales. A gold Buddha statue which features in the film now stands proudly in the village of Portmeirion.

Today, the village is owned by a charitable trust and run by Portmeirion Ltd, of which Robin Llywelyn — a prize-winning novelist and grandson of Williams-Ellis — is the managing director. ‘My grandfather built Portmeirion to demonstrate his ideas,’ he reveals. ‘He hoped it would be some form of inspiration to people, to be creative in their own right.’ When Williams-Ellis died in 1978, at the age of 94, he requested that his ashes be sent up in a firework to drift down over the village — it was a fitting eccentricity. Despite his insistence in later years that Portmeirion had designed itself and that he was merely the medium through which it had bloomed to life, he also described his creation as ‘the architecture of pleasure. I wanted to have something cheerful and encouraging...to get other people interested and excited’. He succeeded. To visit Portmeirion today, a century after its foundation, is to wander through an out-of-time otherworld. No one lives here permanently, although some 260,000 day visitors came calling last year and many of the village’s colourful dwellings can be booked as quirky overnight accommodation. The hotel has a dining room with two AA rosettes and has welcomed everyone, from Beatles lead guitarist George Harrison to Hollywood actress Ingrid Bergman. If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon.

Portmeirion's Pantheon dome looks like a particularly pretty cake topper.

Walking through the village, it can feel as if your gaze is being tugged in four directions at once. There are sculptures and murals, arches and trompe-l’oeils, towering cabbage palms and topiarised yew trees. Somehow, everything comes together as a flowing whole, to the point where it’s easy to forget that the whole ensemble took half a century to complete. The Town Hall, for example, contains a Jacobean plaster ceiling salvaged from a manor in Flintshire — saved by Williams-Ellis after he was alerted to its imminent destruction by Country Life on October 17, 1936 — whereas the cupola that now dominates the Portmeirion skyline didn’t arrive until 1960, after he decided the village had ‘a severe dome deficiency’. ‘Clough used to call Portmeirion “a home for fallen buildings”,’ laughs the village’s location manager Meurig Jones, who regularly welcomes film crews and musicians to the site. ‘Yet there’s nothing that’s thrown together. Everything you see is there for a reason.’

There’s a further factor behind Portmeirion’s place in public consciousness. The Prisoner, Patrick McGoohan’s cult 1960s television show in which the protagonist — known simply as Number Six — is entrapped in a coastal village by mysterious forces, was filmed here. The 17-part series was revolutionary for its time, blending sharp satire with a sci-fi sensibility and, perhaps unsurprisingly, McGoohan and Williams-Ellis forged a natural connection. ‘They were both visionaries,’ believes Jones. As testament to the show’s ongoing popularity, the pink roundhouse that doubled as Number Six’s home is still a Prisoner-themed gift shop. ‘It seems to attract new fans all the time,’ says Louie Roberts, who has worked at Portmeirion for more than two decades and staffs the till. ‘We get people in their twenties from America, young couples from Australia — you name it. I recently had a customer who was in tears. They’d been waiting 50 years to visit.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Angel frescos decorate the window surrounds of one building inside the Italianate fantasy village.

Generally, the village’s longevity also means that preserving the grounds and buildings is — and always will be — an ongoing task. ‘The challenge is to keep the place in a good condition,’ explains Llywelyn, pointing out that even those parts of Portmeirion that have been renovated in recent years will eventually, but inevitably, need further maintenance. ‘That work will never end,’ he adds. Born of a dream, the town is now kept in fine fettle by dedication.

Aptly, various celebratory events, including a 1920s night, are being planned for the centenary of the hotel’s opening next year. Expect them to be spectacular in a way that would have appealed to the village’s founder. ‘He was quite the character,’ says Llywelyn of his grandfather. ‘He wanted Portmeirion to be somewhere that was alive, so he’d be very happy to see it was still flourishing.’

Ben Lerwill is a multi-award-winning travel writer based in Oxford. He has written for publications and websites including national newspapers, Rough Guides, National Geographic Traveller, and many more. His children's books include Wildlives (Nosy Crow, 2019) and Climate Rebels and Wild Cities (both Puffin, 2020).

-

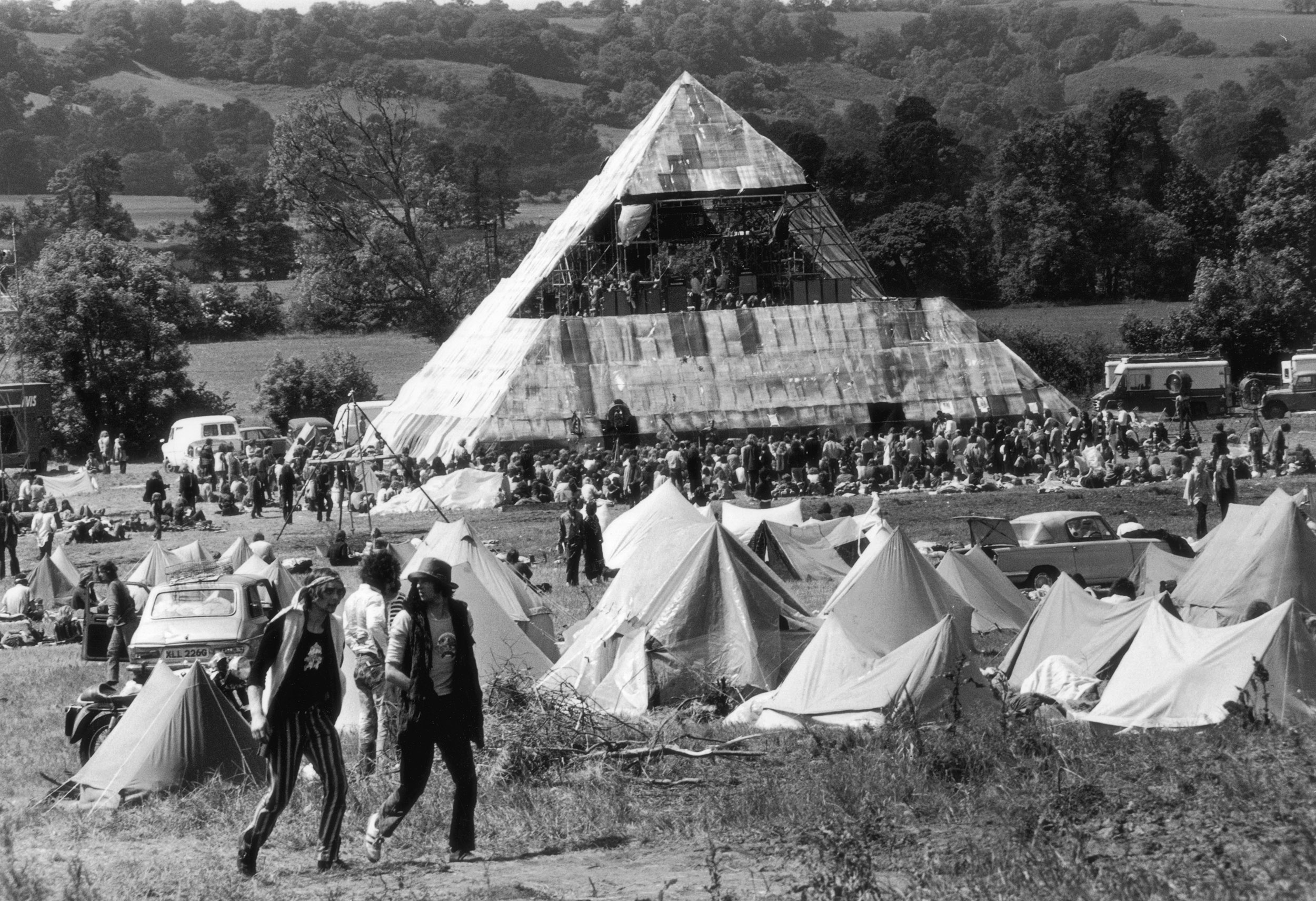

When was the first ever Glastonbury festival? Country Life Quiz of the Day, June 26, 2025

When was the first ever Glastonbury festival? Country Life Quiz of the Day, June 26, 2025Thursday's quiz looks at a landmark date at Worthy Farm.

-

The golden eagle: One of the Great British public's favourite birds of prey — but devilishly tricky to identify

The golden eagle: One of the Great British public's favourite birds of prey — but devilishly tricky to identifyWe are often so keen to encounter this animal that ambition overrides the accuracy of our observations, writes Mark Cocker.

-

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of life

'This is how the countryside looked to Gilbert White, to Thomas Hardy, even to Shakespeare and Chaucer': The forgotten corner of the world where King Charles has poured his energy into preserving an all-but-extinct way of lifeThe historic buildings of a Transylvanian settlement have been restored and preserved with the help of several foundations and backed by The King’s personal enthusiasm. Jeremy Musson reports on this remarkable place; photographs by Paul Highnam.

-

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South Bank

From the Country Life archive: Yes, that is a Moon Transmitter on London's South BankEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home, the house where she penned her final words and drew her final breath

'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed': Inside Jane Austen's Winchester home, the house where she penned her final words and drew her final breathJane Austen spent the last days of her life in rented lodgings in Winchester, Hampshire. Adam Rattray describes the remarkable recent discoveries made about the house in which she died.

-

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to live

Winchester: The ancient city of kings and saints that's one of 21st century Britain's happiest places to liveKings, cobbles, secrets, superstition and literary fire power–Winchester has had it all in spades for centuries and is as desirable now as it ever was, says Jason Goodwin.

-

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up above

The Old House, Dorset: There's beauty up aboveA series of new plasterwork ceilings, collaboratively designed with the creating artist, has transformed the interiors of The Old House, Dorset, the home of Charles and Jane Montanaro. Jeremy Musson explains more; photographs by Paul Highnam.

-

From the Country Life archive: The Maori meeting house in leafy Surrey

From the Country Life archive: The Maori meeting house in leafy SurreyEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan, delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

Stowe Hall and the renaissance of the country house

Stowe Hall and the renaissance of the country houseIn 1975, the end seemed nigh for the great country houses of Britain, but, 50 years on, our built heritage has exceeded expectation and undergone a remarkable revival, John Goodall writes.

-

Glyndebourne House: The 'entrancing' home with an organ so enormous that 'it brought plaster crashing down from the ceiling when it was first played'

Glyndebourne House: The 'entrancing' home with an organ so enormous that 'it brought plaster crashing down from the ceiling when it was first played'Easily overlooked beside the opera that has made its name world famous, Glyndebourne House in East Sussex — home of Gus Christie and Danielle de Niese — bears the architectural stamp of a remarkable 1930s revival, as Clive Aslet explains. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.