How the English fell in love with Versailles, Louis XIV's 'most magnificent and Royal palace'

From 1661 until his death in 1715, Louis XIV invested huge sums of money transforming the Palace of Versailles in France into a creation that commanded international admiration. Philip Mansel considers the response of English visitors to this astonishing creation.

The number and fervour of English visitors to Versailles challenges the legend of eternal rivalry between the two countries. France and England were connected by many ties of commerce, culture and taste and the journey from London to Paris before the advent of the railways could take only two days. Despite frequent wars — 1689–97, 1702–13, 1742–48, 1756–63, 1778–83 — English men and women would be among the most honoured guests, most admiring visitors and most fervent imitators of Louis XIV’s ‘most magnificent and Royal palace of Versailles’, as The London Gazette called it in 1687.

The newspaper was, in fact, reporting on a model of the palace ‘made in copper, gilt over with silver and gold, and of all the gardens and Waterworks’, ‘24 foot in length and 18 in breadth’, that was being exhibited every day, from dawn to dusk, in Exeter Change in the Strand.

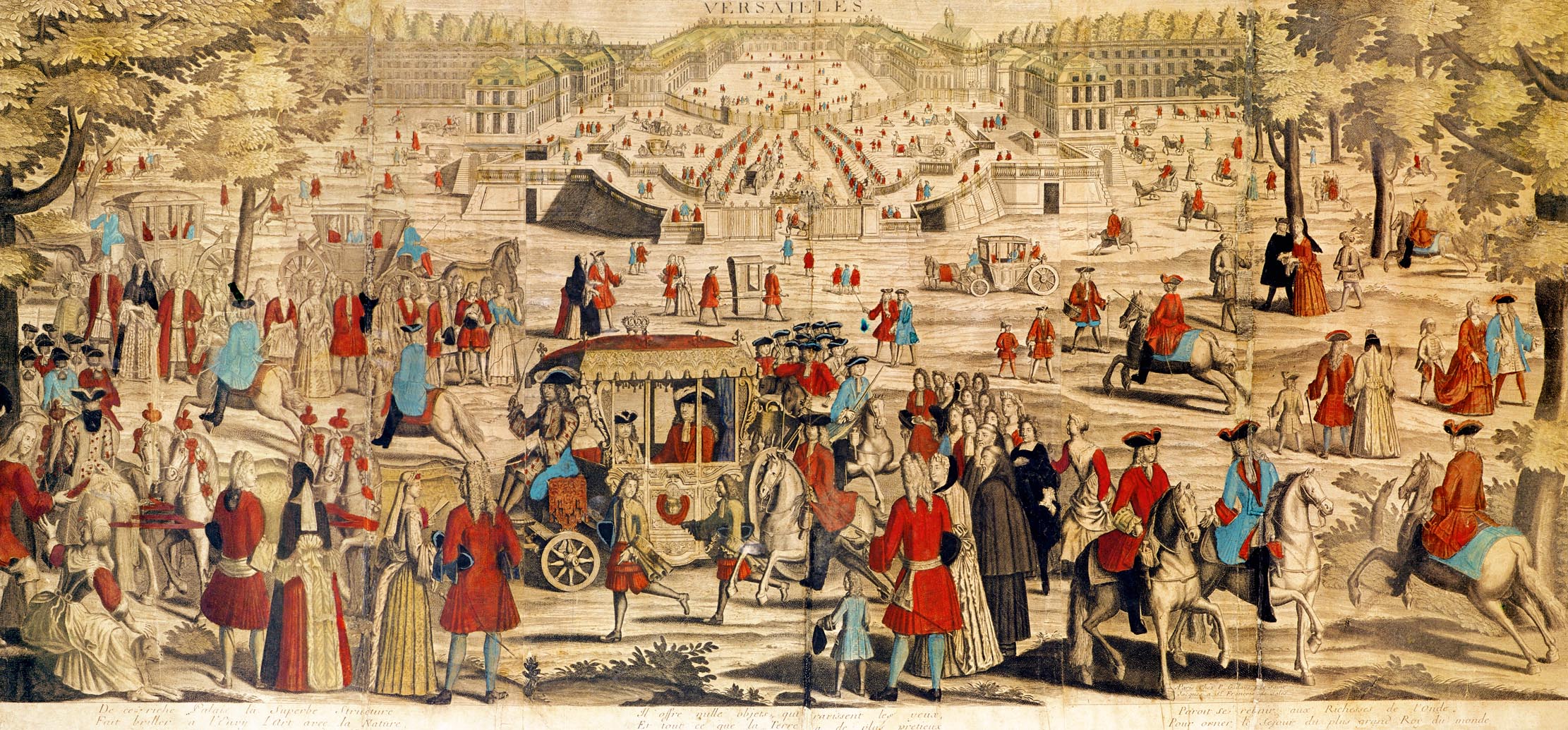

For those able to travel, Versailles was as appealing as the Louvre today, as it held the best of the royal collections of pictures, sculptures and works of art (Fig 1). In 1698, in one of many English books describing Paris and Versailles, the English doctor Martin Lister praised Versailles as ‘the most magnificent [palace] of any in Europe… The esplanade towards the gardens and parterres are the noblest things that can be seen’.

Even the King’s private apartments with his personal collections could be visited, if the King was away and you had a letter of recommendation: Louis XIV had created Versailles to impress Europe, as much as France.

In 1701, another doctor, John Northleigh, similarly praised Versailles as ‘The most beautiful palace in Europe... its Roof glittering with Gold affords a glorious Prospect at a Distance… for statues, canals, groves, grotto’s, fountains, waterworks or what else may be thought delightful, [the garden] far surpasses anything to be seen of this kind in Italy’.

Merchants were no less enthralled and Sacheverell Stevens, after a visit in 1739, particularly praised the grand staircase, destroyed in 1752, ‘composed of the most beautiful marbles’. Several copies were made of this celebrated interior, including one in the early 20th century at Oldway, Devon, derived from engravings (Fig 3). Stevens also praised the ‘exceeding fine… music and singing’ in the chapel. Only the furniture he considered ‘much soiled, far inferior to Windsor, Hampton Court or Kensington’. Writing a guide to the Grand Tour (of which France was no less part than Italy) in 1749, Thomas Nugent called the Palace of Versailles ‘one of the finest in all Europe’; ‘the great marble staircase surpasses anything in antiquity’.

English visitors also admired Versailles for the opportunities it provided to watch the royal family dine in public and attend Mass in the royal chapel (Fig 7). Also in 1749, a naval officer called Augustus Hervey, despite having recently been fighting France, wrote in his diary that he derived ‘uninterrupted pleasure’ from watching the royal family’s dinner, following the royal hunt, going to supper with French friends, and admiring the fireworks at ‘that pile of magnificence and grandeur’, Versailles (Fig 5). He ‘received such an idea of the grandeur of the French court that I had a very pitiful opinion of our own at Saint James’s, nor have I ever altered my opinion, though later so much in it and so long of it’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"English enthusiasm for Versailles suggests that the two nations’ shared taste for monarchy, court life and entertainments could outweigh national antipathies"

Lord Chesterfield, Lord of the Bedchamber to George II, considered a visit to Versailles part of an education. In 1751, he wrote to his son: ‘Go to the King’s and the Dauphin’s levees… an hour at Versailles, Compiegne or Saint Cloud is now worth more to you, than three hours in your closet with the best books that ever were written… Other courts must form you for your own.’

The frescoed enfilades of Boughton, Blenheim and Chatsworth, often painted by the Frenchman Louis Laguerre; the Gobelins tapestries ordered for Goodwood, Newby, Osterley and other English houses; and English patrons’ passion for French furniture, French porcelain and French gardens (before the era of Capability Brown) prove the sincerity of their admiration for Versailles (Fig 2).

Versailles’s peak of popularity occurred during the festivities for the marriages of the grandchildren of Louis XV between 1770 and 1775. Having lost the Seven Years War, the French court was determined to win the peace. Many English people crossed the Channel to watch the fireworks and illuminations in the gardens of Versailles (Fig 4), as well as the entertainments in the palace. Edmund Burke later wrote a panegyric of Marie Antoinette based on his vision of her ‘glittering like the morning star, full of life and splendour and joy’ at her wedding in 1770 (Fig 8).

Another visitor, the Duchess of Northumberland, wrote in her journal that ‘[she] was admirably placed for seeing the ceremony in the chapel… in the same place where the Peeresses stood’. Madame du Barry herself lent the Duchess her house in Versailles and insisted on her ‘sending to her Stables, Kitchen and Cellar as though they were my own’. Louis XV ordered her a dish of coffee of ‘his own roasting, grinding and preparing’.

Versailles was the epitome of the opulence that the Duchess tried to create in her own residences at Alnwick, Syon and Northumberland House. The French courtiers’ clothes, she found, were ‘excessively magnificent’ and the courtiers themselves ‘very polite… very civile to me’. Cards in the Galerie des Glaces and a ball in the newly created opera hall in the north wing (where operas are still performed today) were ‘really a fine sight… such magnificence never [seen] before, nor such crowds’. She also recorded Louis XV’s remark to the comte de Saint-Florentin, Ministre de la Maison du Roi: ‘Monsieur, we are old, but we have never seen so many people nor so much magnificence.’

Another visitor to the festivities, Dr Jeans, also praised their ‘great order and regularity’, the ‘great distinction’ with which foreigners were treated and ‘the profusion of refreshments’. The music at Mass was ‘the finest I ever heard’. For Mrs Thrale, a friend of Dr Johnson, Versailles and its furniture in 1775 surpassed anything she had seen for luxury, splendour and beauty. In 1776, Thomas Bentley, a manufacturer of pottery, was impressed by the palace, the chapel, the theatre, the gallery, the statues in the garden and, again, the public dinner: ‘Their Majesties talked and laughed much at dinner. The Queen is young and very handsome. She appears to be extremely lively and gay, without the forms and attentions that might be expected from her high rank.’

After the French victory in the War of American Independence, the commercial treaty of 1786 was intended to start a new era between the two countries. Its negotiator William Eden was invited to one of the power centres of Versailles: the salon of the duchesse de Polignac, Gouvernante des Enfants de France and favourite of the Queen, on the ground floor of Versailles. Eden wrote in 1787: ‘The evening assemblies at madame de Polignac’s were subjects of greater animadversion than all the extravagance of the court.’ They were probably intended by the King and Queen to enhance the court’s role as a source of hospitality mixing foreigners and ‘a large circle of courtiers of both sexes’; ‘The Queen conversed, played at tric-trac or billiards and often had a concert in which she stood as one of the singers and sometimes a small ball at which she danced.’

Few English visitors admired Marie Antoinette and Versailles more than the Whig leader the Duke of Devonshire and his wife, Georgiana. They had met the Polignacs at Spa and become intimate friends, despite the American War of Independence. More civilised than many contemporaries, the Duchesse de Polignac hated war: ‘Let us end this one, I beg you,’ she wrote in 1779, ‘is it possible that two nations which respect each other, suit each other, seek each other out and love each other so much, should have the rage to destroy each other?’

In June and July 1789, as the monarchy collapsed before the revolutionary National Assembly, the Devonshires were staying in Paris and often visited Versailles. The apathetic Duke came to life in Versailles. ‘He likes Versailles very much and feels himself quite at home in Mme de Polignac’s room… the Duke likes it of all things and goes there Thursday to be formally presented,’ wrote the Duchess of Devonshire. In the Galerie des Glaces on June 28, 1789, on his way to Mass, ‘the King stopped and spoke to Bess [the Duke’s mistress, Lady Elizabeth Foster] and I a great deal. He is less fat, better looking and today was better drest’ than she expected.

Like other English visitors, despite their Protestantism, she was impressed by the chapel: ‘La Messe du roi was amazing fine and inspired one, I think, with a great sensation of devotion. The Elevation of the Host was accompanied by beautiful musick, drums etc and very striking indeed.’ Their friend the Queen ‘received us very graciously indeed, though very much out of spirit with the times… She is sadly altered, her belly quite big and no hair at all, but she has still great eclat’. The couple finally left Paris for Brussels on July 12, missing the Fall of the Bastille by only two days. During the Revolution, the Devonshires would look after the Polignacs’ grandchildren.

English enthusiasm for Versailles suggests that the two nations’ shared taste for monarchy, court life and entertainments could outweigh national antipathies. Francophilia could be as English as Francophobia. The most fervent of all English admirers of Versailles would be a prince who never went there, the future George IV. He not only brought splendour back to the English Court, with the help of massive purchases of the works of art from Versailles that still brighten Windsor and Buckingham Palace today, but also personally intervened in 1814 to support the deposition of Napoleon and the restoration of his friend, Louis XVI’s younger brother, Louis XVIII.

As they bid farewell in a blaze of festivities in London on April 20–23, 1814, Louis XVIII, the Regent and their ministers expressed the hope that, henceforth, peace and trade would unite the two nations. Indeed, in the words of a spokesman for the Corporation of the City of London in his congratulatory address to Louis XVIII, France and England should remain so ‘indissolubly allied by the relations of amity and concord as to ensure and perpetuate to both, and to Europe at large, uninterrupted Peace and Repose’.

For much of the 19th century, that programme would be realised. The last court ball at Versailles would be given in August 1855, by Napoleon III, in honour of a state visit by Queen Victoria, confirming the alliance between the two countries. Unconsciously echoing previous English visitors, she called the ball and supper in the opera house (Fig 6) ‘one of the finest and most magnificent sights we have ever witnessed’.

Philip Mansel’s book ‘King of the World: the Life of Louis XIV’ is out now (Penguin, £30)

The Devon Mansion that dreamt it was Versailles

An outstanding, but little-known treasure faces an uncertain future. Marcus Binney looks at the notable history of this house and

Credit: Christie's - Photo: Evan Joseph Images

An amazing home dubbed the 'American Versailles' has come to the market

It might seem borderline outrageous to liken a house – any house – to the great French royal palace at Versailles.

Credit: Sotheby's International Realty

An astonishing 1,000 year-old château for sale, with gardens laid out by the man who created Versailles

A €15 million château has come on to the market that is one of the finest privately-owned properties in France.

Credit: Savills

A stupendous 18th-century home with gardens that look like they've been borrowed from Versailles, designed by an architect credited as the 'father of wrestling'

Built in the 1700s, this eye-catchingly restored historic house is now available to view in the most modern sense —