How Sir Giles Gilbert Scott left an indelible mark on London — and how that infuriated his critics

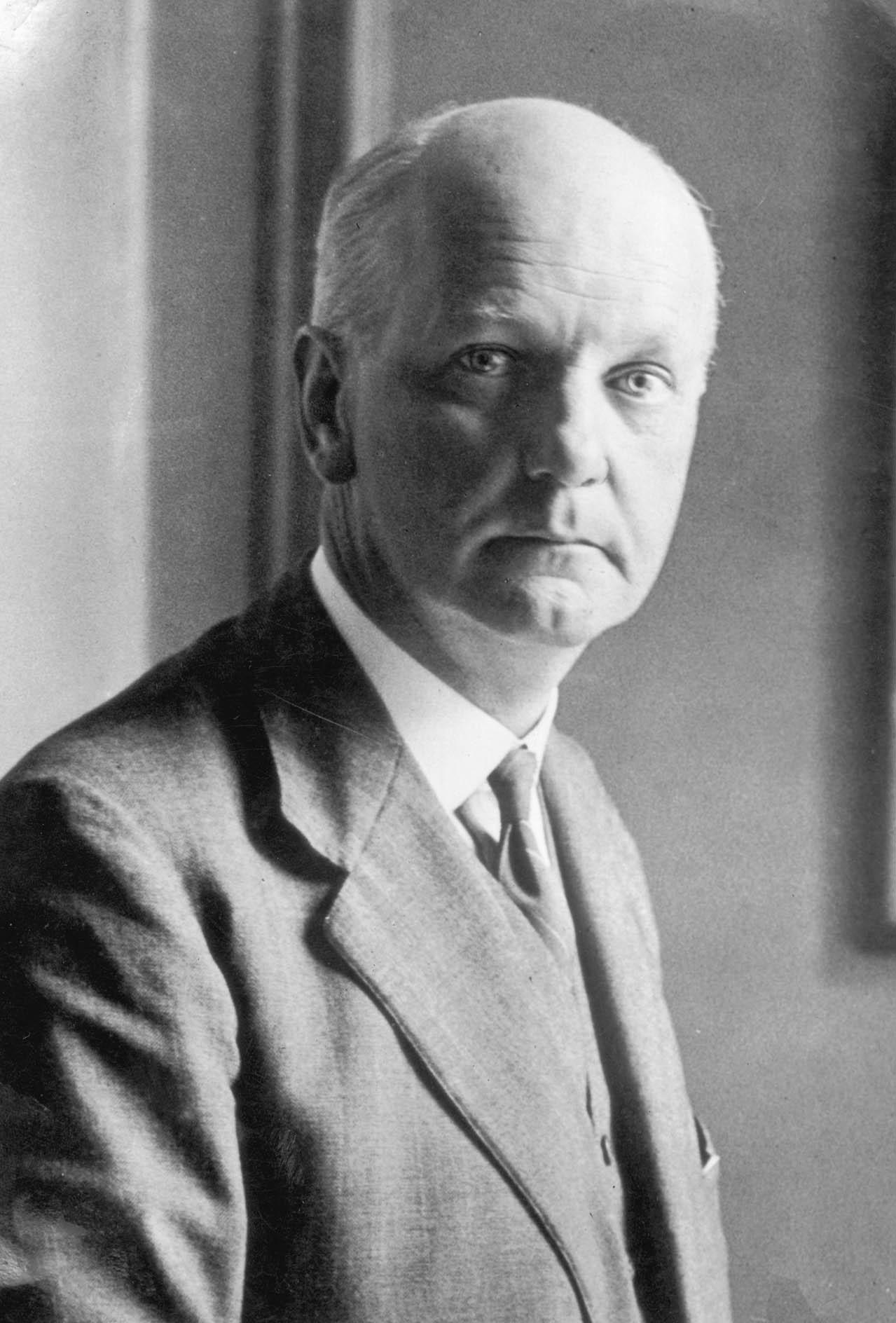

Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s designs shaped London as we know it — but despite his famed ‘unruffled serenity’, not all of his creations were met with rapt enthusiasm. Carla Passino takes a look.

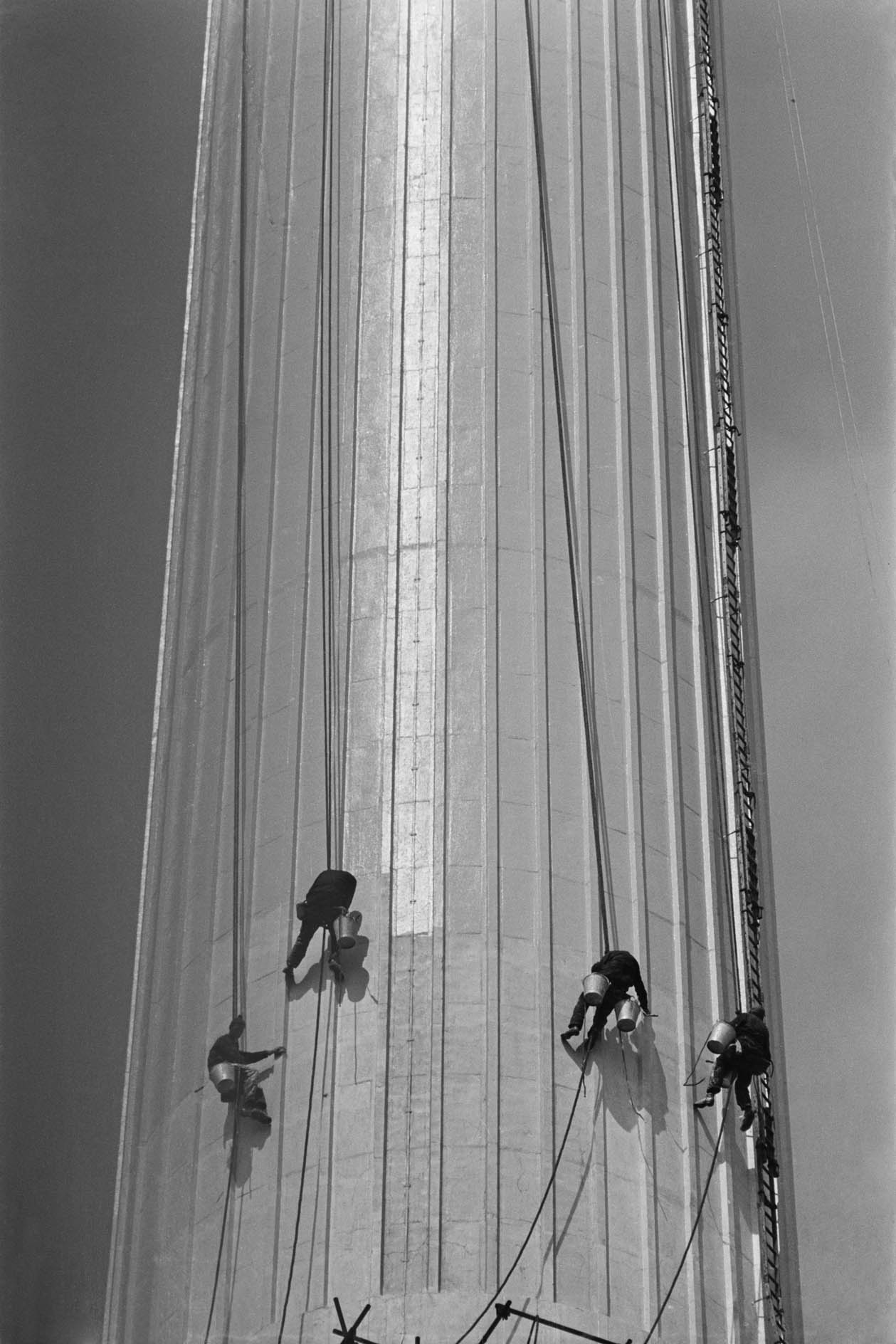

Dignified, almost stately, the Battersea Power Station holds court on the south bank of the River Thames, the stocky panels of the nearby buildings deferring like a respectful retinue to the fluted chimneys that soar like columns of a long-lost Greek temple above the ziggurat of the Boiler House. The plump pig that flew against the station’s black smoke on the cover of the Pink Floyd’s 1977 album Animals may have given way to a crown of steel and glass, but the Grade II*-listed power station remains a much-loved symbol of London. Quite a feat for a place that had originally sparked protests for fear it would be an eyesore.

The man behind this remarkable shift in perception was Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who turned the building’s lumbering bulk into a functional take on a medieval cathedral. He had once said that he couldn’t understand the prejudice against electricity stations, as they could be made quite magnificent; it’s fair to say he was proven right, both at Battersea and at the other London station he designed — Bankside, which is now (with some conversion help from Herzog and de Meuron) Tate Modern.

‘His power stations must remain one of the more powerful reminders of his skills of design — transforming a utilitarian hulk of a building into an edifice with composition, finesse and a beguiling, timeless elegance,’ says Robbie Kerr of ADAM Architecture. ‘His use of brick-work is brilliant. And now, both buildings are living examples of adaptive reuse in the most captivating ways.’

Although he shaped the skyline of the Thames’s southern bank perhaps more than any other architect until Renzo Piano built The Shard, Scott had his breakthrough in Liverpool. The grandson of Gothic Revival master Sir George Gilbert Scott, he was articled to one of his grandfather’s former pupils, Temple Moore, when he entered a competition to design Liverpool’s new cathedral in 1902 — and won. His age (early twenties) and his religion (Roman Catholic) caused disquiet among the cathedral committee members, who imposed another of Scott Snr’s former pupils, George Frederick Bodley, as joint architect.

The two had a tempestuous work relationship, which only ended when Bodley died in 1907. Free from shackles, Scott modified the cathedral’s design and it was a triumph: The Times in 1922 hailed it as a ‘magnificent example of Modern Gothic in which he… surpassed the tradition of style bequeathed him by his grandfather’.

Liverpool Cathedral propelled him to fame, election to the Royal Academy (in 1922), a knighthood (in 1924) and even marriage — when staying at Liverpool’s Adelphi Hotel, he had met and fallen for receptionist Louise Hughes, whom he wed in 1914. But it also became a lifelong project: the cathedral was only completed in 1978, almost two decades after his death. Nonetheless, this did not prevent him taking commissions elsewhere.

In London, in particular, Scott variously turned his hand to colleges (the University of Roehampton’s Whitelands College, in Putney, and, as an associated architect, the Salvation Army’s William Booth Memorial Training College in Camberwell, the tower of whichhints at the Bankside power station); infrastructure (Waterloo Bridge, as well as power stations); theatres (the unusually neo-Classical Phoenix, on Charing Cross Road); breweries (the now demolished Guinness building in Park Royal, with its daring aerial bridges) and, of course, churches (Kensington’s Our Lady of Mount Carmel).

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, ‘the most distinctive addition to London’s architecture must be the red telephone box,’ notes Mr Kerr. ‘It so distinctively, definitively and strongly marks our streets. It is part of the London identity.’

Scott chose to top this most mundane of structures with a dome inspired by Sir John Soane’s mausoleum and it worked. First came ‘kiosk no. 2’, delightful, but expensive to construct, then the rare, ‘pale K3’ and, in 1935, a more streamlined version, the ‘no. 6’, which would festoon Britain with domed bursts of red.

Of homes, however, Scott only built a handful — at least until the Battersea Power Station conversion considerably, if posthumously, upped their number. Maida Vale has Cropthorne Court, a bold sequence of projecting angles and receding arches; Marylebone has the more restrained 22, Weymouth Street, which he designed with his brother Adrian, and Paddington has Chester House, which Scott created for himself. It’s a model of elegant simplicity, an evolution of Georgian architecture, which forges its own identity rather than merely replicating a style of the past (he shunned slavish traditionalism and extreme modernism in equal measure). But, perhaps most remarkably, it was, as C. H. Reilly wrote in Country Life in 1926, a home with ‘a general air… of great happiness’ (undoubtedly helped a great deal by the fact that ‘everything in the interior [seemed] faced with fine surfaces easy to keep clean’).

Not all of Scott’s work was universally acclaimed. Waterloo Bridge was mired in controversy — mostly over the demolition of the preceding structure and it is the one design of which Mr Kerr is not fond, dismissing it as ‘such a dull statement’ in the context of the South Bank on one side of the Thames and Somerset House on the other. Nor did Scott’s plans for Coventry Cathedral please the Royal Fine Arts Commission, so much that he eventually pulled out of the job.

But this was nothing compared with the uproar caused by the proposal to build the Bankside power station — an ironic turn of events for someone who had already rescued an almost identical project from public opprobrium. Complainants warned that the new building would obstruct views of St Paul’s, damage it with its fumes, and even, bizarrely, dwarf it — from the far bank of the Thames. It must have been a fortune, then, that Scott ‘bore life’s triumphs and life’s trials with an unruffled serenity,’ as Sir Hubert Worthington wrote in 1960. Or perhaps he had fathomed what would eventually happen: that, as The Times put it in 1960, ‘when the station was built, little dislike of it was expressed’.

A project in which Scott did not succeed, however, was the overhauling of London’s traffic — which he must have felt keenly, not least because, belying his unprepossessing nature, he had a penchant for fast motors. He advocated a ‘drastic surgical operation’, according to a 1943 story in The Times, arguing, with Shakespeare, that ‘all things are ready if our minds be so’.

But even the man that had managed to change an entire city’s views over power stations — twice — failed to sway the planners and, as he predicted, London’s traffic remains ‘muddle and chaos’ to this day.

The story of the red telephone box, one of the iconic emblems of 20th century Britain

The red telephone box has been part of the landscape of Britain for a century. Jack Watkins takes a look

Credit: Paul Highnam / Country Life Picture Library

The Cathedral of Christ, Liverpool: The fascinating story of Britain's largest cathedral

The architect who created the red telephone kiosk and the London power station today occupied by Tate Modern also designed

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon