How M.R. James wove country house architecture into his ghost stories

In his ghost stories, M. R. James had a perceptive eye for architectural detail, as Jeremy Musson explains and Matthew Rice evokes in specially commissioned drawings.

M. R. James wrote of his preference for ‘malevolent or odious’ ghosts, noting that local legends may contain ‘amiable and helpful apparitions’ but he had ‘no use for them’. His tales are disturbing in part for their convincingly described and often superficially appealing settings — cathedrals, clerical residences, hotels or country houses with endless, shadowy, portrait-filled rooms.

In The Ash-tree (1904), the bachelor don speaks through the narrator about the ‘strong attraction’ of even mildly second-rate, small country houses, describing those of Eastern England as ‘rather dank little buildings, usually in the Italian style, surrounded with parks of some 80 to a 100 acres’.

He notes their noble trees and oak paling, their ‘pillared portico perhaps stuck onto a Queen Anne house which has been faced with stucco, to bring it into line with the “Grecian taste” of the end of the 18th century’; their double-height halls ‘open to the roof’, and libraries ‘where you may find anything from a Psalter of the 13th century to a Shakespeare quarto... I wish to have one of those houses, and enough money to keep it together and entertain my friends in it modestly’.

The tale of Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance (1911), begins with another scholarly bachelor, who has inherited his estranged uncle’s estate at ‘Wilsthorpe’ in Eastern England. As Mr Humphreys comes up from the station, the reader shares his first impressions of an ‘oddly proportioned’ building, a ‘very tall red-brick house with a plain parapet concealing the roof almost entirely. It gave the impression of a townhouse set down in the country’.

Mr Humphreys is pleased to discover the house has a large library, with three windows facing east, where he could imagine himself being ‘especially happy’. He is at this point yet to discover the horror that lies in the garden, with its semi-abandoned maze.

James’s ghost stories were originally devised as entertainments to be read aloud at Christmas, by candlelight. The first audiences were friends gathered in his rooms in King’s College, Cambridge, where, from 1887 to 1918, he was fellow, dean and then provost (he was also director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and vice-chancellor of the university).

The first two ghost stories date from 1893 and James was persuaded into publishing his first collection of stories in 1904, but they have since overshadowed their author’s reputation during his lifetime as an expert on medieval manuscripts and the Apocrypha (curiously, he edited the earliest English compilation of ghost stories, written in the 15th century by a monk of Byland, Yorkshire).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The brilliance of his unsettling evocations of ghosts draws on his deep knowledge of the depiction of demons in medieval manuscripts. At the same time, although partly inspired by the Gothic tales of Sheridan Le Fanu, James’s stories occupy a more modern idiom, even when set in the past; he was a fan of escapist fiction, including the detective stories of Agatha Christie, and often used contemporary settings for his tales.

Born in 1862, James grew up in a Georgian rectory in Great Livermere, Suffolk, country houses, including that of the widow of his friend James McBryde, who illustrated his first story collection, but died young in 1904. Mrs McBryde lived first at Woodlands in Herefordshire, then at Dippersmoor Manor (‘Old Dippers’), an ancient manor that she restored from a tenant farmhouse.

James also stayed with the Croppers at Ellergreen in Westmorland and with the Stirling-Maxwells at Corrour in the Highlands. His cousin, Lady de Saumarez, lived at Shrubland Park in Suffolk and James also enjoyed the hospitality of Oliver Locker-Lampson, at Newhaven Court, outside Cromer.

He was a guest of the Lyttletons at Hagley Park and his close friend Sir Mark Sykes Bt lived at Sledmere Park in Yorkshire, where the vast Classical library has been suggested as the inspiration for the library in A Neighbour’s Landmark (1925). For all this socialising, congenial house parties are never evoked in his stories, which focus instead on private families, unmarried squires and visiting bachelor-scholars.

Lost Hearts (published in Pall Mall magazine in 1895) is a chilling tale of child sacrifice, set in a country house called Aswarby Hall, Lincolnshire, in 1811. This is the only real house name to appear as a setting in his stories and Robert Lloyd Parry, editor of Ghosts of the Chit-Chat (2021), suggests it was an in-house joke when the story was first read aloud in 1893, the same year that Sir George Whichcote, 9th Bt, a recent graduate from Magdalene College, inherited Aswarby Hall. James would have probably heard about the house (and the inheritance) through his Eton friend Harry Cust, whose family seat, Belton House was also in Lincolnshire.

The real Aswarby, however, bore little relation to James’s version, in which a young boy alighting from a post-chaise sees ‘a tall, square, red-brick house, built in the reign of Anne; a stone-pillared porch had been added in the purer classical style of 1790; the windows of the house were many, tall and narrow, with small panes and thick white woodwork’. There are additional wings ‘connected by curious glazed galleries’ and in the evening sun ‘the window-panes glow like so many fires’ — a metaphor that evokes one of the Arcadian park views of Richard Wilson or architectural renderings of Joseph Gandy, as well as suggesting the danger posed by the crazed alchemist lurking inside the hall.

The Ashtree presents a similar kind of late-Stuart house; this time Castringham Hall in Suffolk, a ‘square block of white house, older inside than out’. With its Italian portico, this is a building that had ‘well-nigh attained its full dimensions in the year 1690’ and the story refers to the baronet Sir Richard enlarging the church’s family pew and disturbing the grave of a witch.

Castringham Hall had been a fine block of the mellowest red brick, but Sir Richard is ‘a pestilent innovator’ who has travelled to Italy, become ‘infected with the Italian taste’, and is ‘determined to leave an Italian palace where he had found an English house’. Now, ‘stucco and ashlar masked the brick’ and ‘some indifferent Roman marbles were planted about in the entrance-hall and gardens’.

Despite thinking it created ‘a less engaging aspect’, the narrator concedes the work ‘was much admired, and served as a model to a good many of the neighbouring gentry in after-years’. The ash tree of the title grows close to the house and proves a conductor of deadly menace.

Appearing in the same 1904 collection is The Mezzotint, a story in which a university museum curator of topographical prints acquires an example of what is described as ‘the worst form of engraving’; this being ‘a rather indifferent mezzotint’, showing a solid Queen Anne house. The image features a full-front view ‘with three rows of plain sashed windows with rusticated masonry about them, a parapet with balls or vases at the angles, and a small portico in the centre. On either side were trees, and in front a considerable expanse of lawn’.

However, on a second inspection, the picture has acquired the back view of a figure at the edge of the print and, on a third viewing, this figure is crawling on all fours toward the house. The next day, the curator asks a friend to describe it; he sees no figure, but notes that: ‘The house has one — two — three rows of windows, five in each row, except at the bottom, where there’s a porch instead of the middle one’ and he notes that ‘one of the windows on the ground-floor — left of the door — is open’. At this, the curator exclaims: ‘My goodness! he must have got in.’

A final viewing shows the figure striding out of the picture holding a captive child. The house is eventually identified as Anningley Hall in Essex, where the infant child of the last owner disappeared mysteriously one night (the bereft father being the creator of the haunted mezzotint). In a nod to the Ashmolean, Oxford, the image, by now static, is consigned to the ‘Ashleian Museum’.

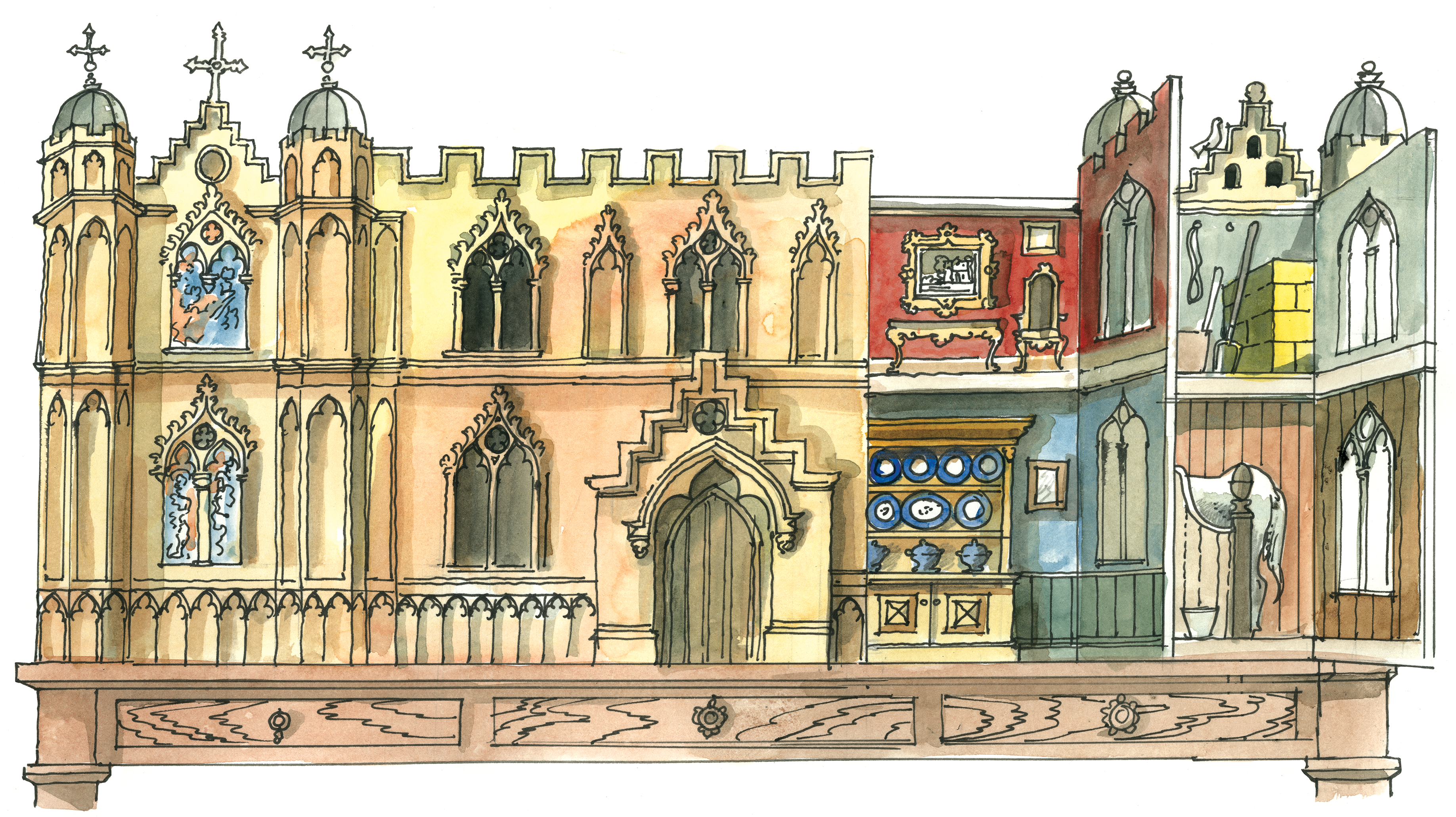

The Haunted Dolls’ House was a contribution to the library of Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, an exquisitely furnished gift offered to Queen Mary. In this spine-chilling 1922 story, another bachelor collector, Mr Dillet, acquires a Rococo Gothic dolls’ house, which he feels is the ‘Quintessence of Horace Walpole, that’s what it is: he must have had something to do with the making of it’. James describes the house with relish, but in a way that suggests he was not an admirer of the style.

‘It was quite six feet long, including the Chapel or Oratory which flanked the front on the left as you faced it, and the stable on the right. The main block of the house was, as I have said, in the Gothic manner: that is to say, the windows had pointed arches and were surmounted by what are called ogival hoods, with crockets and finials such as we see on the canopies of tombs built into church walls. At the angles were absurd turrets covered with arched panels’.

The chapel is prettified Gothic, with ‘pinnacles and buttresses, and a bell in the turret and coloured glass in the windows’. The stable to the right was a full two storeys, with coaches, horses and grooms.

The front of the house opens to show an interior, in this case with four large rooms: bedroom, dining room, drawing room and kitchen, ‘each with its appropriate furniture in a very complete state’. According to the narrator: ‘Pages, of course, might be written on the outfit of the mansion — how many frying-pans, how many gilt chairs, what pictures, carpets, chandeliers, four-posters, table linen, glass, crockery and plate it possessed; but all this must be left to the imagination.’

A passage no doubt intended to amuse the antique-collecting Queen Mary adds that: ‘I will only say that the base or plinth on which the house stood... contained a shallow drawer or drawers in which were neatly stored sets of embroidered curtains, changes of raiment for the inmates, and, in short, all the materials for an infinite series of variations and refittings’. Needless to say, the fictional dolls’ house (identified later in the story as a scaled-down version of — fictional — Ilbridge House, Coxham, East Anglia) produces more in the way of horror than delight.

In the last ghost story James wrote before his death (A Vignette, 1936), the reader is asked ‘to think of the spacious garden of a country rectory, adjacent to a park of many acres’. Within a belt of ancient trees, a rectory and the landowner’s house and its park are connected by a gate with a hole cut into it, through which a ghost watches a small boy.

Evoking James’s childhood at his father’s rectory on the edge of the parkland of Livermere Hall, the story suggests troubling memories of the estate, which was being dismantled in the uncertain years following the First World War. James was a conservative-spirited man and the recollection of this stately house he had known since early childhood being demolished in 1923 must have resonated with the generation of First World War losses, which included many of his friends and young charges from his Cambridge days. These haunted him always, perhaps more than the demons of his beloved manuscripts.

Inverailort House, the Highland home for cabinet ministers, land reformers, crofters, playwrights, the occasional Russian prince, plus dozens of cats and 50 chickens

Joe Gibbs sheds a tear over the decline and fall of Inverailort House, an archetypal Highlands institution of a type