How Chequers has changed — and stayed the same — in a century, as pictured in Country Life

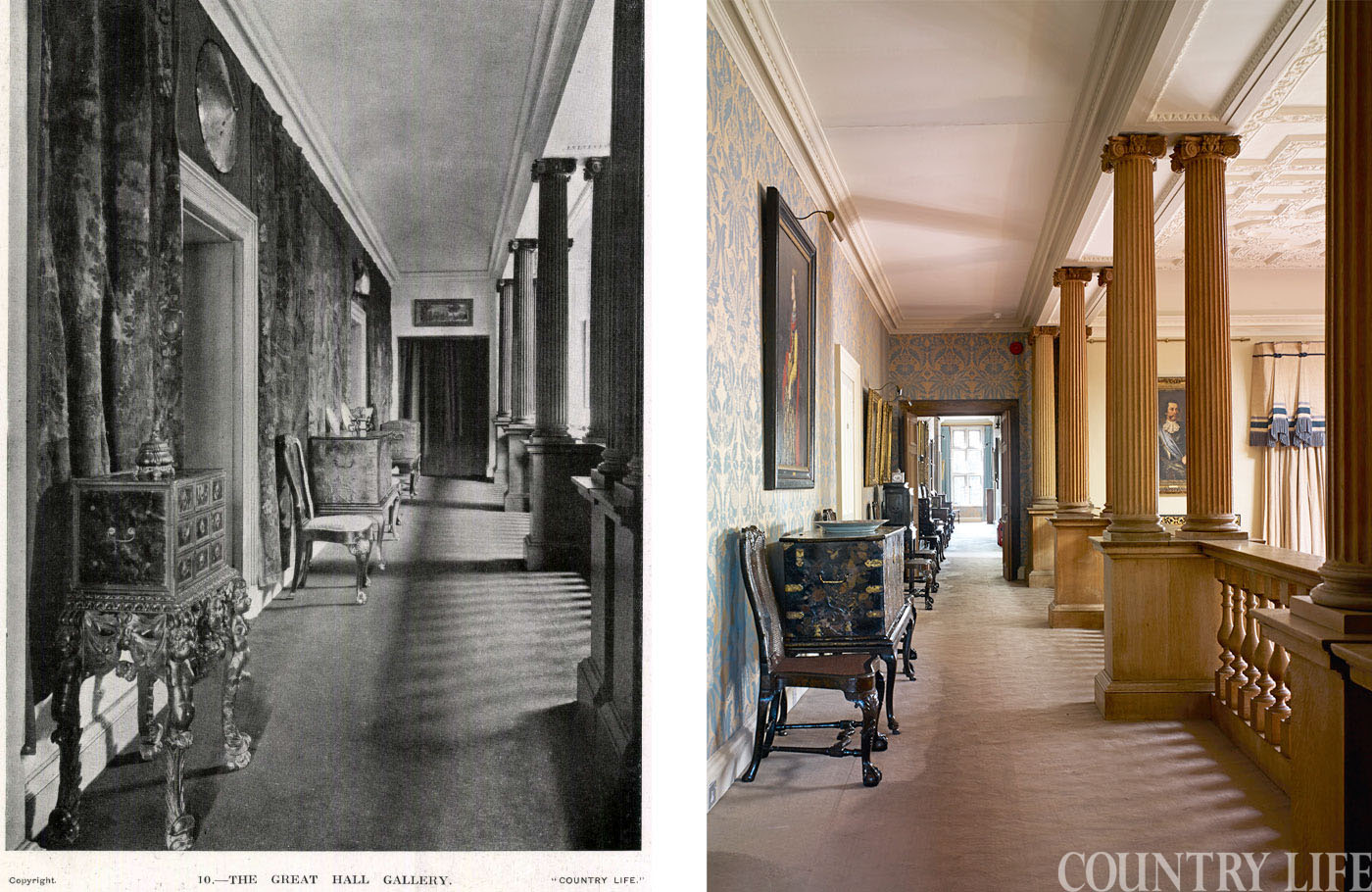

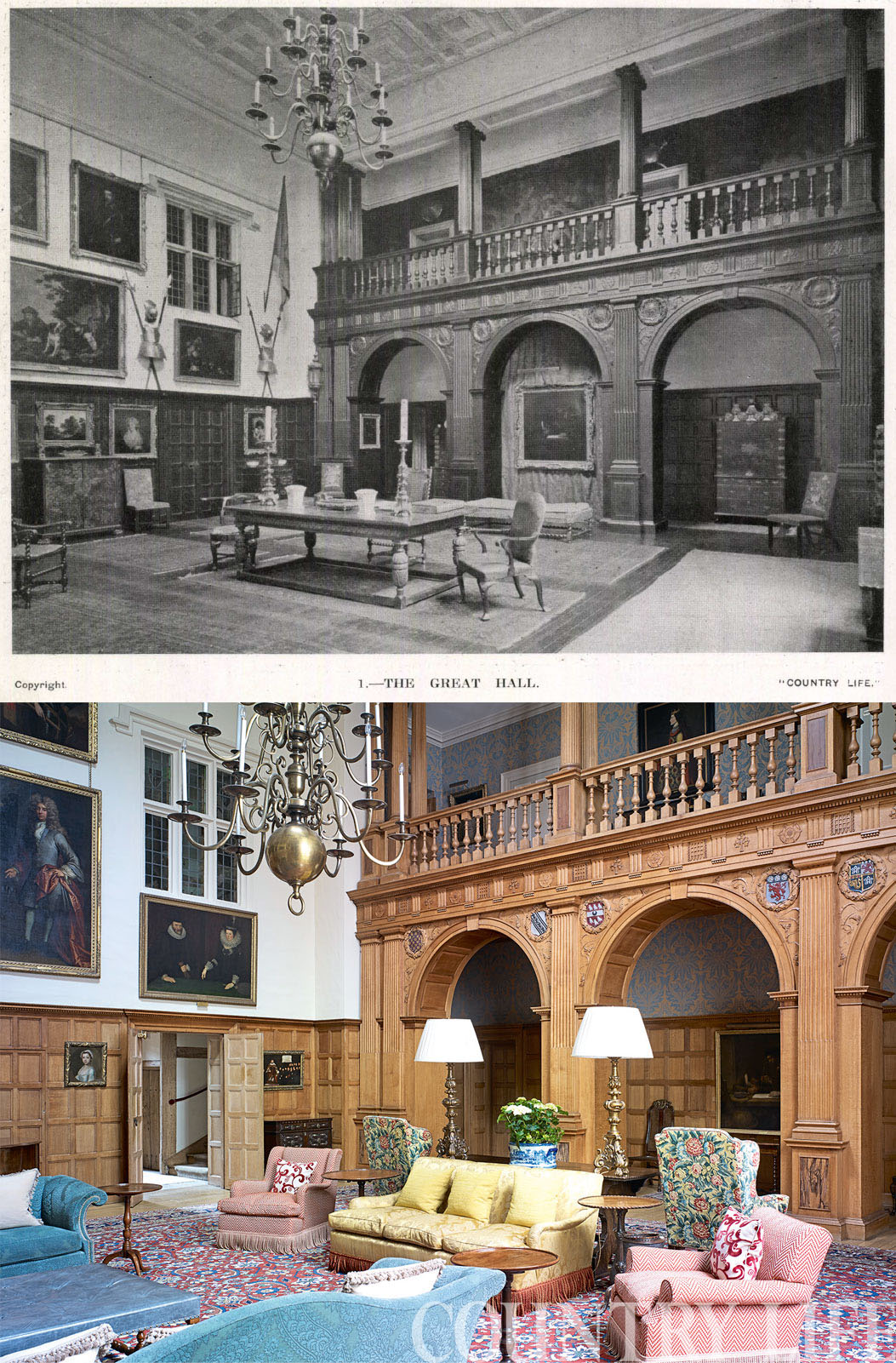

We take a look at Chequers is now, and as it was 103 years ago, when Country Life visited following the decision by its previous owner to donate the country house to the nation.

Every Tuesday afternoon, we take a look back at an article from Country Life's treasure trove of architectural treasures from the archive. Today, we look at some of the images from a series of pieces written about Chequers, the official country residence of the British Prime Minister.

Chequers is the subject of a two-part piece by John Goodall in the May 6 and 13 editions of Country Life magazine. In October of 1917, it had similar treatment — albeit over three parts — by Avray Tipping, who told the tale of the house following the news that it was to be donated to the nation by Sir Arthur Lee and his wife, Ruth. The handover would not take place until 1921; ever since then the house has been the official country residence of the sitting prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Sir Arthur and Lady Ruth who had spent several years (and a small fortune) restoring the house to its original grandeur — and undoing work carried out a century beforehand which had transformed the original house with a series of Gothic flourishes which Tipping clearly disapproved of.

Victorian Gothic architecture has a healthy following now and buildings such as George Gilbert Scott's St Pancras are venerated. Yet Tipping clearly felt about it as many now feel about the concrete blocks of the late 20th century.

His view was by no means unusual at the time. Its architects were charged with hatred of beauty, and Oxford's Keble College was labelled the 'ugliest building in the world'. Yet even in this opening to his piece, he admits that the future may view things differently. Plus ça change...

Chequers is to be the future country home of British Prime Ministers. Such is the generous and patriotic resolve of its present owners. Sir Arthur and Lady Lee came to this most delightful Buckinghamshire seat some ten years ago, and at once began conservative reparations. The principle on which they were broadly projected and admirably executed was to give back to the house, within and without, the full character and flavour of the times when it originated, while modern habits of life should find scope and gratification.

Mainly built under Elizabeth, it had, as we know from family documents, escaped with scarce any alteration until a hundred years ago much money was spent in obliterating its history and its beauty under a pervading coat of mock medieval frippery, so pleasing to its perpetrators that the unhappy place was described in 1823 as 'lately fitted up in the Gothic style with exquisite taste.'What this exquisite taste was like future ages may still learn through the medium of photography. Such presentment will have documentary value for a future history of the rise and fall of Art, but the relegation of the stuff itself to the rubbish heap is not likely ever to be regretted. It is well to preserve examples of every phase of architecture and decoration. There is always the best of a bad lot.

Nor must we forget that man is habitually unappreciative and destructive of what the next preceding generation has done, although later on it may again be valued. The Strawberry Hill manner may, therefore, have future devotees, but they should have left for them complete creations in that taste and not palimpsests set over a truer style.For the Gothic of 1820 was not a true style. That surely may be stated, not as a passing whim, but as a permanent principle. It imitated in paltry and superficial fashion the forms of an age of which it ignored the spirit, the purpose and the methods. It was third-rate theatricalism; not well considered creation or copying.So Chequers is well without it, for it has been replaced, as the illustrations show, by a careful return to sixteenth and seventeenth century models wherever the original fabric called for such owing to wreckage and defacement. Wholehearted has been the attention and affection which Sir Arthur and Lady Lee have bestowed on every department and detail that make up the full entity of this complex work of art.

Raglan Castle: How the last great medieval castle in Britain became a Renaissance palace — and a Civil War ruin

We look at the remarkable story of Raglan Castle, near Abergavenny, by delving into the Country Life archive.

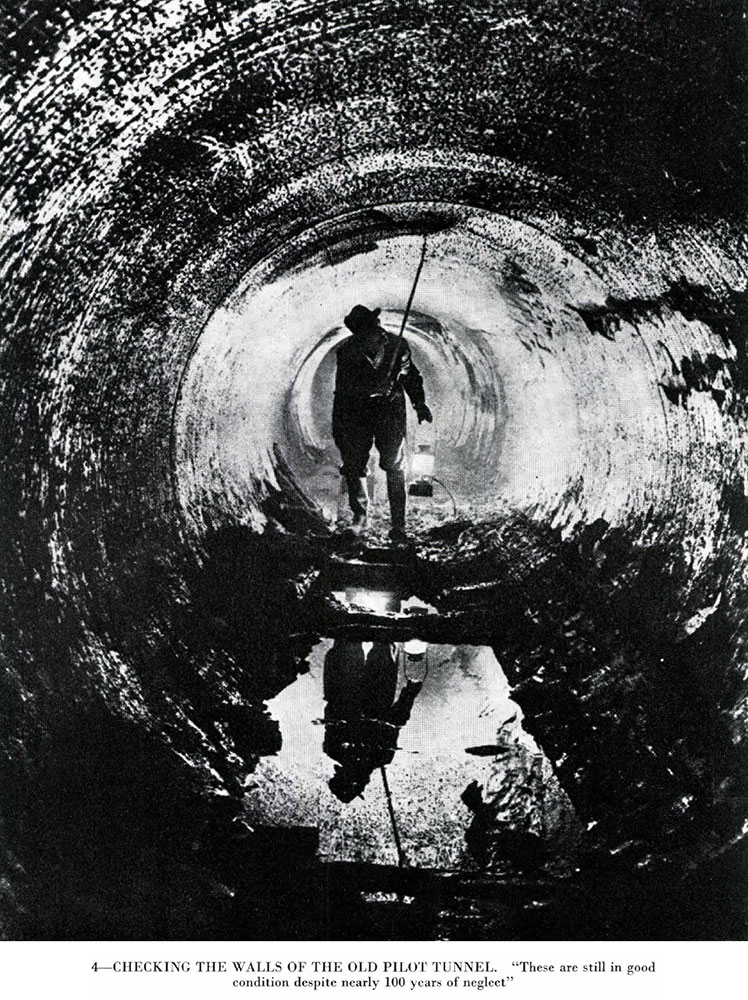

The Channel Tunnel's centuries-long shift from fear of 'foreign hordes' who'd 'deface the countryside' to our magnificent link to the Continent

This week's architecture archive looks at the two centuries' worth of plans which eventually resulted in the Channel Tunnel between

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Voewood, the 'supreme example' of a butterfly-plan house in Norfolk's beloved Poppyland

Country Life's Mary Miers praised the eccentricities of the Arts-and-Crafts style in a piece from our archives published in 2009,

Clovelly Court: The Devon country estate pulling off the vital trick needed by a modern country estate

Every Tuesday, we go back through the Country Life archives to enjoy an article from the past — this week,

The stunning salvation of Castle Howard, one of the greatest houses in Yorkshire — and, for that matter, the world

The Herculean efforts which saved Castle Howard's architecture and collections after a devastating fire in 1940 have lasted for decades;

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museums

Athena: We need to get serious about saving our museumsThe government announced that museums ‘can now apply for £20 million of funding to invest in their future’ last week. But will this be enough?

By Country Life

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer Hebrides

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer HebridesAn improving landlord in the Outer Hebrides created a remote Georgian house that has just undergone a stylish, but unpretentious remodelling, as Mary Miers reports. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By Mary Miers

-

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model village

Life in miniature: the enduring charm of the model villageWhat is it about these small slices of arcadia that keep us so fascinated?

By Kirsten Tambling

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson

-

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the world

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the worldSir Edwin Lutyens became the de facto architect of one of Britain's biggest financial institutions, Midland Bank — then the biggest bank in the world, and now part of the HSBC. Clive Aslet looks at how it came about through his connection with Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar careerClive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in London

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in LondonBy Toby Keel