How 'an insatiable appetite for brass-band music' gave rise to the bandstand, and how we almost lost them all

From Handel to Bowie, our bandstands have been a hub for free live music for centuries, as well as being buildings of architectural interest.

Consider, for a moment, the traditional sounds of a British summer: the soft jangling of china crockery on a picnic blanket; the thwack of willow hitting leather on a village green; the politely ordered cacophony of a brass band ‘tuning up’ for a bandstand concert on a sunny afternoon. The latter, an endearing reminder of our Victorian forefathers’ obsession with genteel outdoor pursuits and a belief in the virtue-inducing power of music, was, until recently, at risk of almost being lost to the nation forever.

Parks and recreational areas in our towns and cities proliferated in the 19th century as a foil to increasing industrialisation and urbanisation. The introduction of the Select Committee for Public Walks in 1833 provided public access to green spaces, encouraging ‘a better use of Sundays’ that would also improve both the quality and longevity of urban dwellers’ lives. Music — that most democratic and morally upstanding of popular art forms — was seen as a way of enticing people into those spaces.

To serve as a stage — and shelter for musicians from that other great staple of the British summer, rain — the forerunner of the bandstand was a multi-storey pavilion where the band played on the uppermost level, as constructed in London’s Vauxhall Gardens by entrepreneur Jonathan Tyers in 1735. Built on land leased from the Duchy of Cornwall that had drifted into use, unofficially, as a form of rural brothel, Tyers’s intention was to create an alternative ‘diversion that may polish, without corrupting, the mind’.

His pavilion — or ‘orchestra stand’, as it was then known — was, like the gardens themselves, ‘a sophisticated vision of Arcadian beauty to appeal to the most romantic sensibilities’, as Paul Rabbitts describes in his definitive guide Bandstands: Pavilions for Music, Entertainment and Leisure. George Frideric Handel became a de facto composer-in-residence and the pleasure gardens, together with their orchestra stand, flourished.

However, by 1859, competition from newer parks, such as nearby Crystal Palace, forced Vauxhall’s closure and the pavilion’s fittings, complete with organ, were auctioned off for a total of £99. It was not until two years later, at the Royal Horticultural Society’s gardens in South Kensington, that the bandstand as we currently know it (made of iron and wood and covered by a domed roof) came into being, designed by Capt Francis Fowke of the Royal Engineers. Two of them featured in the London International Exhibition of Industry and Art the following year.

A golden age followed, with up to 1,500 bandstands springing up in parks, on piers and on promenades all over Britain, spurred on by the country’s insatiable appetite for brass-band music. As Mr Rabbitts explains: ‘In the 1880s and 1890s, the brass-band movement was huge, with up to 40,000 bands operating up and down the country. At Corporation Park in Blackburn, more than 50,000 people turned up at one event to listen to 11 brass bands play — it was the equivalent of going to Hyde Park today to see Bruce Springsteen.’

The popularity of bandstands continued until the outbreak of the Second World War, when materials for building and maintenance were needed elsewhere and their ornate ironwork was removed and melted down to make weapons. After the war, a jubilant public preferred the easy charms of cinema and television to the moral edification of Victorian-era concerts.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

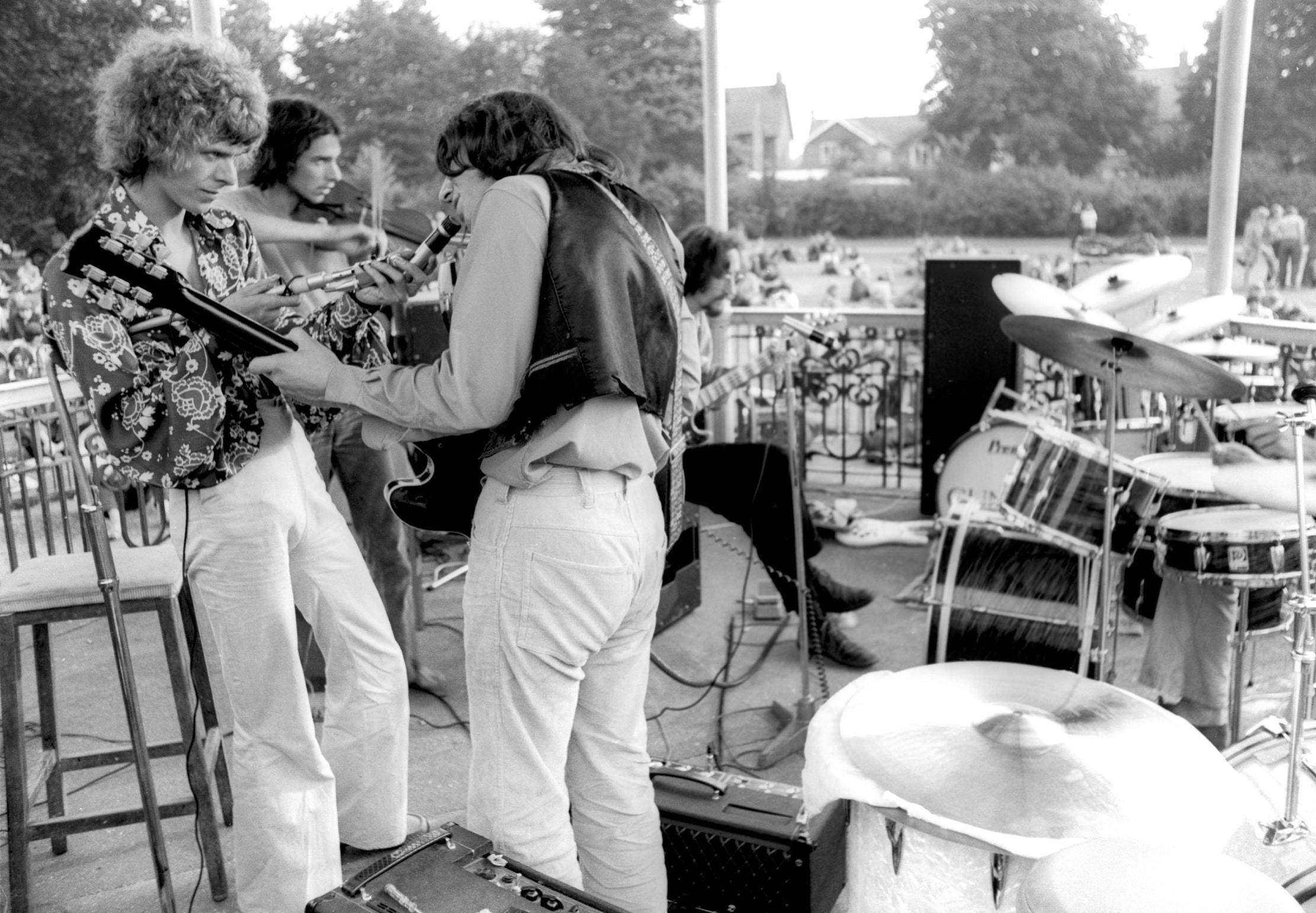

A temporary revival in the late 1960s saw Pink Floyd play at Parliament Hill bandstand on the capital’s Hampstead Heath and David Bowie perform — and, it is believed, pen the words to his 1973 hit, Life on Mars? — on the steps of Beckenham bandstand in the London Borough of Bromley (restored this year), but this wasn’t enough to prevent numbers from steadily declining to less than 500 by the late 1980s. Of those bandstands that remained, most were languishing in a woeful state of disrepair due to neglect, vandalism and lack of public finance.

A renewed interest and investment in our cities’ outdoor spaces, however, combined with refreshed zeal for anything that enhances mental and physical wellbeing, has led to a rejuvenation of Britain’s parks and gardens — including their bandstands. The National Lottery Heritage Fund has been instrumental in that revival by providing funds for park regeneration projects that, since its inception, have helped to restore more than 120 bandstands to Victorian levels of splendour.

‘The National Lottery was set up in 1994 and one of the very first projects it funded was focused on public parks,’ explains Drew Bennellick, head of land, sea and Nature policy at the National Lottery Heritage Fund. ‘Bandstands are a really important animation of parks. Not only for the fact they bring activity and life through the events that are held on them, but also because a lot of those bandstands are a part of the parks’ original Victorian designs, either as landmarks or focal points.

For instance, the bandstand in the middle of Clapham Common is still a landmark today. People often meet there and it helps them navigate their way around. Bandstands are an integral part of a park, rather like a hall or staircase might be in a historic country house.’

A true devotee of the British bandstand, Mr Bennellick shares in the enjoyment of these pieces of Victoriana, which he has helped to preserve for a contrastingly modern age to appreciate in a reassuringly traditional way: ‘My dad lives in Sevenoaks in Kent, opposite the Vine Cricket Ground, which is one of the oldest in the country. The Vine has a beautiful bandstand (built in 1894, next to the cricket pavilion) and they have concerts on a Sunday afternoon. It’s a wonderful place to be and a classically British thing to do — just sitting in a deckchair, listening to the sounds of summer.’

'What else can you do but say "it's completely disgusting"?': Britain's worst new buildings, with Charlie Baker and the Carbuncle Cup

The Carbuncle Cup returns after a six-year hiatus. Competition judge and magazine editor Charlie Baker speaks to James Fisher about

Gatewick: The 'Georgian' house that was built from scratch in the 1950s

A combination of discerning architectural improvement and collecting in 1950s Sussex created Gatewick — the former home of Charles, James

Elegant and congruous: How Hartland Abbey draws together eight centuries of architectural and family history

John Goodall looks at the history of Hartland Abbey in Devon after the Reformation, and its descent in the hands

How the country houses of Britain proved perfect for the Allied Forces to get ready for D-Day

Country houses great and small were indispensable to D-Day preparations, with electricity and sanitation, well-stocked wine cellars, countesses to run

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life