How a 'scarred and degraded' landscape became a 21st century Reptonian marvel with a dream country house at its heart

A landscape previously used for intensive farming has been turned into the setting of an idyllic new country house in a classical idiom. Jeremy Musson reports; photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

The success of a new country house depends, in large part, on how it reads within its landscape setting and Wield Park, near Alresford in Hampshire, designed by Francis Terry and completed in 2020, is an inspiring example of a house rooted in the history and character of its surroundings (Fig 6). It shows exactly what can be achieved in a project of close collaboration between a far-sighted client, an experienced architect and a top landscape designer.

At the core of its story is the revival of the landscape to designs by Christian Sweet of Colson Stone Practice. To come across its newly planted parkland, its expansive curved lake and carefully judged parkland tree plantings, is to enjoy a vision of inspired design and land management that imparts a 21st-century Reptonian thrill.

In this project, Mr Terry worked closely with the clients, Andrew and Arabella Dunn. As a highly experienced residential developer, Mr Dunn relished the challenge of a new country house, which he instinctively felt should be of a traditional character. At Wield Park, he and the architect sought to create a home in the spirit of a Hampshire manor house of the late 17th century, but with generous modern plan forms and light and airy interiors. In this sense, we might describe Wield Park as the very essence of the ‘English country house revisited’ in the 21st century.

The previous use of the site for intensive agricultural purposes had left a badly scarred and degraded environment, served by a modest modern brick farmhouse. For those who can remember that lost view, the transformation is almost unbelievable.

The subtle, but still confident Classicism of the house reflects Mr Terry’s experienced eye (Fig 2). He was educated amid the faded temples and Classical pile of Stowe School before studying architecture at Cambridge. For two decades, he worked for — latterly in partnership with — his father, Quinlan Terry, champion of the tradition of Classical architecture. They collaborated on important new country houses, such as Ferne Park in Dorset (Country Life, May 5 and 12, 2010) and Kilboy in Ireland (Country Life, September 7, 2016). He set up his own practice, Francis Terry & Associates, in 2016 and is well established as a leading country-house architect.

Mr Terry describes his approach as an ‘intuitive’ response to place, as well as to the character of his clients, noting how often childhood homes become part of the discussion with clients about the houses in which they want to live and raise their own families. Mr Terry studied painting and has exhibited at the Royal Academy, an element that brings an additional quality to his design processes. His ‘skill in drawing and the handling of light and shadow’ was noted by the late Prof David Watkin in his 2015 book The Practice of Classical Architecture: the Architecture of Quinlan and Francis Terry, 2005–2015.

At Wield Park, the project’s collaborative approach included advice from Rural Solutions, to obtain planning, and work by Alex Jaggs, head of the team at Finchatton, which delivered to the highest level on the construction and all aspects of the interior. The author of this article was also involved on the project as an expert design reviewer. From the start, the design aimed to be what is described with reference to planning legislation as a ‘Paragraph 80e’ house, defined by the National Planning Policy Framework. That is to say it would show exceptional design quality rooted in the characteristics of local buildings. Without deviating from that aim, planning permission was, in fact, ultimately granted under the replacement-dwelling policy.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The result bears witness to a highly considered programme of work. It reflects the beauty of building in a traditional style, yet incorporates a contemporary vision of family life, expressed in a fluid, open interior plan (Fig 1) and generous bedroom spaces. The design of the house was informed by a full survey of local historic architecture — both polite and vernacular — and the typical well-ordered elevations that characterise so many of the country houses of Hampshire, from the mid 17th to early 19th century.

In terms of ‘classical continuity’, it is interesting to reflect how this house can be linked to the principal country house in the near vicinity, Moundsmere Manor, which was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and built in 1908–09 in an ambitious late-17th-century or neo-Wren style. Blomfield, who wrote The Formal Garden in England (1892), also laid out the gardens there and the estate features a pair of lodges in a simplified neo-Georgian style. Other Arts-and-Crafts and Classical-inspired houses that became part of the design conversation include nearby Marsh Court by Edwin Lutyens — a dramatic clunch-built house on a sloping site near Stockbridge, constructed for the investor Herbert Johnson in 1901–04 — and Lutyens’s stone-built Middleton Park in Oxfordshire, created in the 1930s for the Earl of Jersey and his American countess. Airy 1920s Long Island houses, combining English and French influences, with their notably generous scale and fluid plans, also played a part in discussions about the evolving design.

The precise positioning of the new house is a crucial factor in its success. The modern farmhouse that previously stood on the site was located higher up the slope and on the same level of the ancient woodland, whereas the new site was chosen to be lower. Therefore, the new house is sheltered in the contours of the landscape and allows views to the north-west, without breaking into the well-established treeline. This allows for a more private, terraced garden area south of the principal range, created to designs by Mr Sweet, and for the parkland to sweep up to the house to the north and west. There was a strong sense that the building should gracefully ornament the revived landscape: not dominate it, but give it a pleasing visual focus. Mr Sweet took inspiration from major examples of Humphry Repton’s work for the way they engage with their surroundings to develop a new plan.

Having studied landscape architecture at Thames Polytechnic, Mr Sweet is partnered by his wife, Debbie, at Colson Stone Practice. Based in Somerset since 2005, their work on historic gardens and landscapes includes Endsleigh in Devon, Caerhays Castle in Cornwall and Kenwood House in north London — all places strongly associated with Repton. Their work on Villa Balbiano on Lake Como, Italy, won the Society of Garden Designers’ historic restoration award. Their projects are always rooted in an understanding of the history of each landscape setting.

That Wield Park sits comfortably into its setting is partly the result of the overall shape of the house and its building materials. Wield Park’s service wing and lower buildings to the west are built of traditional Hampshire red brick, with clay tile roofs. By contrast, the main house is constructed from pale, but warm Yorkshire limestone, from quarries operated by Cadeby Stone, which Mr Terry regards as a highly versatile stone for building. This manages to echo the local clunch-building tradition in a more durable form and references the grander Hampshire houses of the later 17th century, such as Wolvesey Palace in Winchester. Traditional grey slate has been used for the main roofs, which are punctuated by dormers with segmental pediments.

The main entrance elevation is broken up by a central recession of three bays between shallow one-bay projections, in the late-17th-century manner. Although echoing Lainston House, near Winchester, this is also reminiscent of Repton’s Sheringham Hall in Norfolk, which gave the inspiration for the long porch supported by simple, paired Tuscan columns. The single-storey canted bay windows on each of the external bays offer expansive views across the park and provide balconies to the bedrooms above, where Serliana windows add a bold Palladian touch. On the western garden elevation, there is a striking contrast of material between the stone elevations and brick chimney stacks. The south-facing façade repeats the overall design of the entrance side, but its views engage with the formal garden terraces and lawn, looking up to the ancient woodland above. The different play of light gives the façade a contrasting feel.

Internally, the plan creates a splendid interior enfilade from the ‘everyday’ entrance to the west, where the service range is clustered with a guest cottage and garaging to form something like a traditional stable yard. The long enfilade (Fig 3) begins in the service range and leads past the kitchen — an ingenious galleried design that evokes something of the interior of a yacht (Fig 5) — a dining room (Fig 7) and sitting room, then beyond through the double-height, south-facing stair-case hall, into the light and airy principal drawing room to the east (Fig 8).

The first floor has a similar long, broad corridor connecting bedrooms and bathrooms; the principal bedrooms enjoying floor-to-ceiling views from the Serliana windows (Fig 4). Above this, attic-level bedrooms form enjoyably eccentric spaces, rather like spacious tent rooms within the roof pitch and given further depth by the dormers. Some of the most engaging moments of the house are unexpected glimpses between interior and exterior; for instance, the glimpse from the staircase hall of first-floor oval windows on the return of the projecting bays.

In early discussions about the landscape, Mr Sweet presented the client with an image taken from Repton’s Red Book for Kenwood, showing a view across the bathing ponds, with a low bridge, sinuous drive and dense woodland beyond. This helped determine the overall concept for Wield Park. One-third of the 370-acre site consisted of ancient woodland, all now under a management plan to enhance its ecological diversity. The new landscaping is like the house itself, subtle and bold, it is carefully graduated and the park designed as grazed pasture in the local tradition.

The scale of the operation needs to be recognised: six acres of new trees have been added to the ancient woodland, together with 300 individual parkland trees in shaped groups throughout the new parkland, mainly oak, but with beech, sweet chestnut, lime, some cedars and London plane. A total of six acres of new water has been introduced in a sequence of lakes and ponds, following the valley bed, as well as hedgerows of mixed hawthorn, blackthorn, cornus and holly.

All in all, this rich landscape enhancement of the house is the final touch to complete the poetic transformation of this formerly degraded agricultural property, into a dream country house in the English spirit.

The practice of landscape: 10 great gardens by Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton was the leading garden-maker at the turn of the 19th century. Here are 10 of his best-loved gardens

Humphry Repton: How the legendary gardener embodied the spirit of his age

The leading garden-maker at the turn of the 19th century, Humphry Repton (1752–1818) was a man of feeling, as well

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

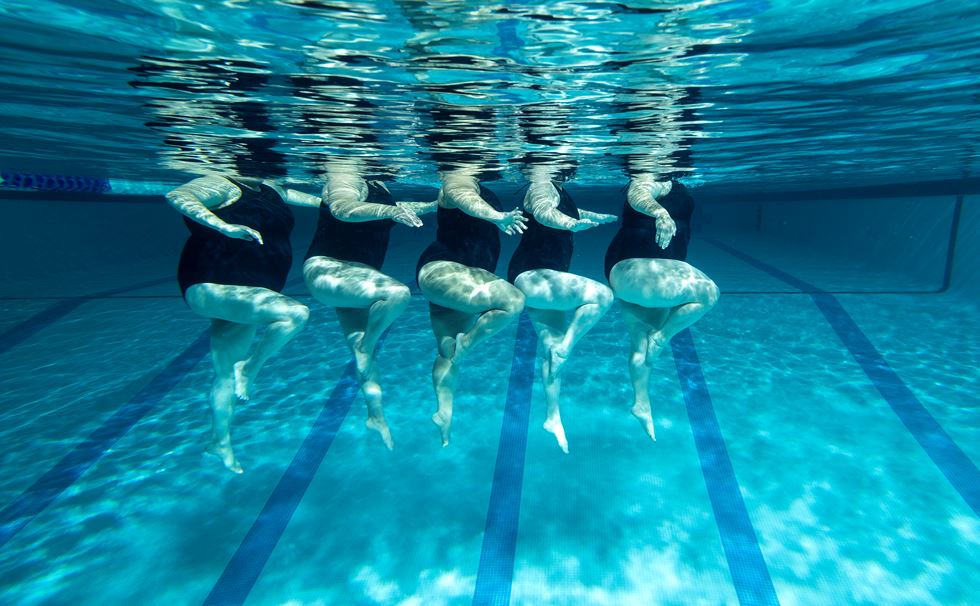

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes