The history of Lincoln College, Oxford: Salvaging the vine

John Goodall describes the initiative of a Bishop of Lincoln to establish Lincoln College, Oxford, and the long struggle to bring it to fruition. Photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

On October 13, 1427, Richard Fleming, Bishop of Lincoln, was authorised by royal licence to found a college with a Rector and seven scholars in the church of All Saints’ on the High Street of Oxford. According to the licence, issued with the assent of Parliament — Henry VI was only five years old at the time — the new foundation was to be called the ‘College of the Blessed Virgin Mary and All Saints of Lincoln in the University of Oxford’.

It unified a trinity of neighbouring parishes, linking All Saints with St Mildred’s and St Michael’s North Gate, the first to be served by the college community and the latter two by hired chaplains. The college as a whole was charged to pray for the King and successors in life and death, the Bishop likewise and all the faithful departed. In addition to the parochial revenues of the three parishes, the college was permitted to hold property up to the annual value of £10.

The royal licence — the first seed of what has become familiarly known today as ‘Lincoln College’ — described a religious foundation that was, in some ways, typical of its period. In a world where the intervention of God in day-to-day affairs was an acknowledged reality, there was an active desire to harness prayer for the needs of the living and the dead. It was relatively common, therefore, for the wealthy to constitute religious communities of clergy variously within their households, as independent bodies or attached to parish churches. Parishes so dignified normally had a familial association with the patron either as their birthplace — a case in point is the college at Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire, founded in 1425 by Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury (later the founder of All Souls, Oxford) — or dynastic burial church, as with that established by the Duke of York at Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, in 1415.

In addition to their prayers, colleges were often charged with charitable or practical responsibilities, such as the provision of alms to the poor or education. In Oxford itself, the establishment of colleges connected to the university had a history extending back into the 13th century. Before the 1420s, most had been founded by bishops, a reflection of their responsibility for the training of clergy, the central function of the university. Bishop Richard’s college followed in that tradition, but also reflected his personal experience and concerns.

Fleming had been born in Yorkshire in the 1380s, seemingly of gentry stock, and entered the church. That brought him to Oxford by 1403, where he had documented connections with two colleges, University and Queen’s. He also briefly hired a school from Exeter College. All these institutions are strikingly proximate to his own. The central concern of the university in this period was dealing with the heretical views of the Oxford theologian John Wycliffe. His criticism — and that of his followers or Lollards — of the ecclesiastical hierarchy became bound up both with the social upheaval connected to the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381 and the destabilising scandal of the Great Schism in the Latin Church from 1378–1417. It was partly in response that, in 1379, Bishop William of Wykeham established the leviathan Oxford foundation of New College for the training of clergy, a defining building in University’s architectural tradition (Country Life, October 16 and 23, 2019).

Fleming was notably successful within the university, where he was credited with developing a new method of disputation, a structured debate on set texts for the purposes of teaching. He also worked on the international stage on behalf of Henry V and, by way of reward, was offered the Bishopric of Lincoln in 1420. The see extended in a vast sweep from the Humber estuary in the North to the Thames valley in the South, embracing Oxford and the university within its jurisdiction. Three years later, in 1423, Pope Martin V further promoted him to the Archbishopric of York over the head of an elected candidate; the results were personally disastrous. In England, the fractious minority administration of Henry VI took control of the diocese of Lincoln, which they chose to consider vacated, but refused to recognise Fleming’s elevation to York. It was not until 1426 that a deal was brokered, whereby Bishop Richard, complaining of acute financial difficulties, dropped his claims to York and was fully restored to Lincoln.

Concurrently, over the 1420s, the University of Oxford was itself contemplating an ambitious new project, the construction of a purpose-built space for disputations in theology, the so-called Divinity Schools (Country Life, April 5, 2017). Land for the building was secured in 1427 and it’s possible that Bishop Richard was directly prompted by this initiative to undertake his own college, conscious that his see needed to be institutionally visible within the developing university. Regardless, the scale of his foundation makes painfully apparent how meagre his resources were.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Using the revenues of three Oxford parishes — none of them wealthy — was effectively a diversion of income (the churches had been appropriated by the Bishopric of Lincoln for nearly a century) and the annual property revenue of £10 would have paid a good salary for only one priest. The Bishop’s decision to attach the college to All Saints, where the community was clearly intended to celebrate Divine Service, perhaps reflects its proximity to the University Church of St Mary’s and his awareness of its relative prominence; then, as now, the spires of the two churches command the High Street.

In the meantime, Bishop Richard remained focused on the problem of heresy. Indeed, in 1428, he was prompted by Pope Martin V to enact the decade-old anathema pronounced by the Council of Constance and ordered the bones of the long-dead John Wycliffe to be disinterred from the churchyard at Lutterworth, Leicestershire, to be burnt and scattered in the River Swift. He also seems to have set in motion plans to establish another college at Boston, Lincolnshire, although the project never materialised. It’s possible he aimed to pair it with his Oxford college in modest emulation of the late-14th-century school and university Wykehamist foundations of Winchester College, Hampshire, and New College, Oxford.

Whatever the case, he formally united the three Oxford parishes to constitute Lincoln College in April 1429 and issued a foundation charter eight months later on December 19. In 1430, several land purchases were made within the densely developed streetscape north of All Saints’ Church (Fig 2), presumably with a view to creating a coherent building plot. It’s very unlikely that any construction got underway, however, because Bishop Richard himself died suddenly on January 25, 1431. He is buried in Lincoln Cathedral, where his monument (Fig 7) and chapel survive. Nor is it clear if anything further substantive happened at Oxford before the death of the first Rector three years later. He was replaced in May 1434 by one John Beke, previously vicar of St Michael’s.

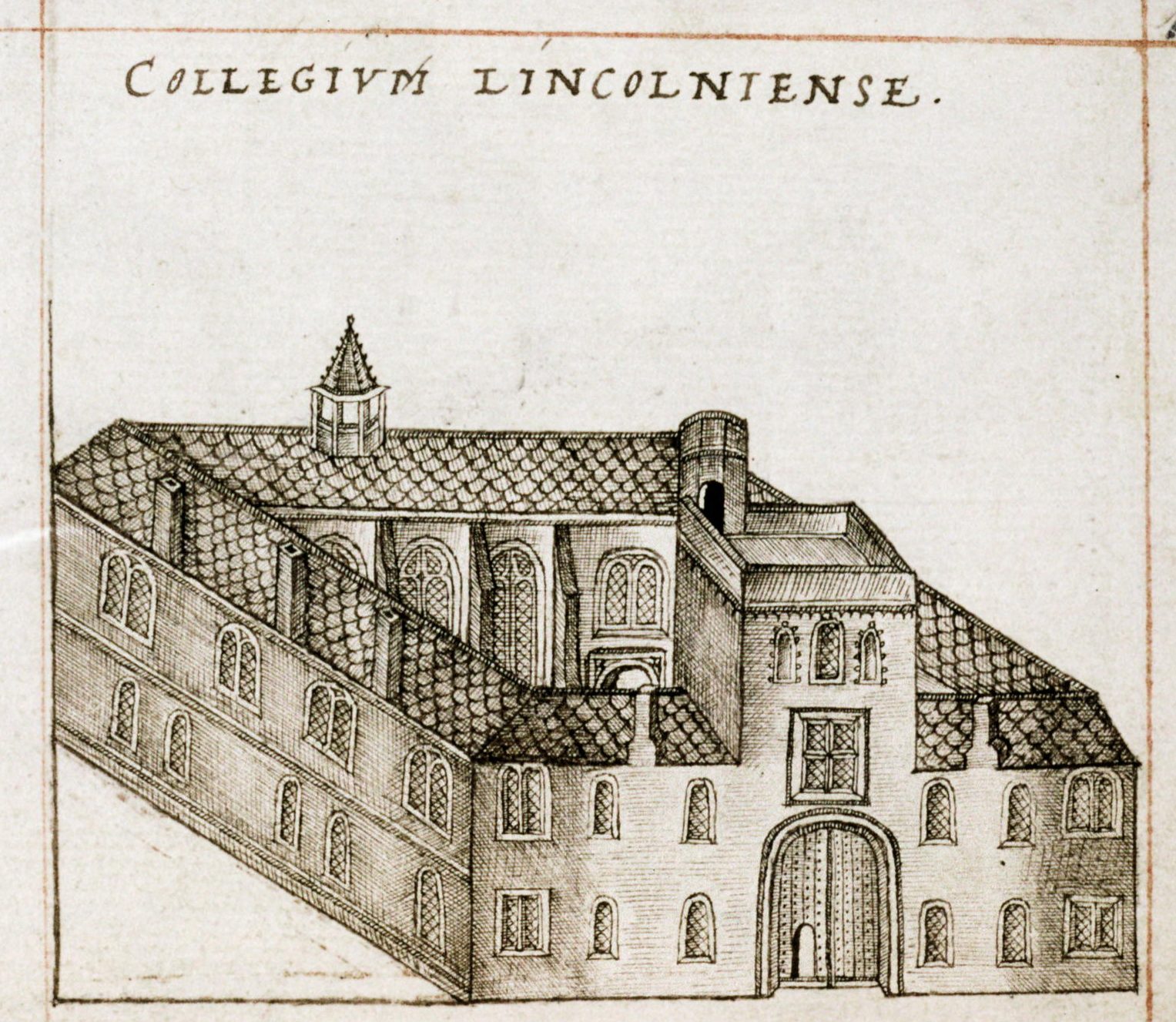

Beke is credited with really getting the college off the ground, somehow attracting the patronage of John Forest, an aged and wealthy pluralist, who became recognised as a co-founder. Among other livings, he was a prebend of Lincoln — so, presumably, had known Bishop Richard — and Dean of Wells. He may also have been a composer. Forest is described in a document of June 6, 1437, as having ‘built the college as a whole, the chapel with the library, the hall with the kitchen, rooms above and below, of noble workmanship and decent form’. In other words, three sides of what is today the front quadrangle: a gatehouse (Fig 6) and lodgings range to the west; a north range incorporating a chapel and library (Fig 1); and a hall (Fig 4) with attached services — which still operate — to the east. To create this group of buildings, the site had to be cleared and the church of St Mildred demolished.

There are no building accounts to identify the designing mason of the college, but the sophisticated detailing of the east hall door bears technical comparison to work at the Divinity Schools undertaken by William Winchcombe. Carvings of beasts ornamented the gables of the ranges above the intersection of Brasenose Lane and Turl Street (the former site of St Mildred’s church). Such ornament was not unusual, but it was popularly admired. As early as the 1690s, Celia Fiennes observed that Lincoln was ‘overlook’t by the Devil’; clearly, the figures had been pointed out to her. The sculptures were removed in the early 18th century, but one was replaced for the Millennium. In 1899, a copy of the celebrated ‘imp’ of Lincoln Cathedral, now also the college rowing mascot, was installed over the hall door (Fig 3).

The accommodation of the chapel within a quadrangle range — rather than as a freestanding building — is paralleled in several smaller Oxford colleges. Its inclusion suggests an important departure from Bishop Richard’s plans in 1427; the community’s regular round of daily prayer was now to be removed from its original intended parochial context in All Saints Church. The chapel was only licensed for use in 1441/42 and that may imply that Forest’s buildings were finished after 1437. Whatever the case, the college gradually began to attract small bequests and, in 1445 and again in 1447, Henry VI issued licences that permitted it to increase the value of its endowment to £50 per annum.

Following the accession of Edward IV in 1461, the new Yorkist administration looked with a predatory eye on religious foundations established under Lancastrian rule. To protect its endowment, Lincoln College sought reconfirmation of Henry VI’s various charters. That done — and presumably through the connections of Forest — the executors of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, Thomas Beckington, were persuaded after 1465 to make a generous bequest of £200 towards the foundation. Some of this money was spent on extending the existing hall range to create a residence for the rector and Bishop Beckington’s arms, as well as a carved device or rebus representing his name — a ‘beacon’ and ‘ton’ or barrel (now confusingly garbled in restoration) — survive on the building.

In the 1470s, the question of Henry VI’s grants unexpectedly reared its head again. The 1461 confirmation had been carelessly drafted and the college turned for help to its official visitor, the Bishop of Lincoln, Thomas Rotherham. According to Robert Parkinson, a Fellow writing in 1569 or 1570, the Bishop was exhorted in a sermon to complete the college with reference to a passage in Psalm LXXX that describes a vineyard planted by God, but left abandoned. According to Parkinson, ‘these words… so moved the bishop that he immediately answered the preacher that he would do what he asked’. By tradition, a vine has existed in the college ever since, its place more recently taken by a huge Virginia creeper.

Whatever spurred him to the task, Bishop Rotherham did effectively re-found the college (he also, incidentally, later founded a college in his own native Rotherham, South Yorkshire). On June 16, 1478, he secured letters patent confirming all Henry VI’s charters and enlarging the number of fellows from seven to 12, the number of the Apostles. To accommodate these, he closed in the entrance quadrangle with a fourth range of chambers to the south (Fig 5) and issued the first set of governing statutes. These are dated February 11, 1479, and purport to be based on the statutes drafted by Bishop Richard, being prefaced by a florid text attributed to him. This describes the purpose of this ‘little college (collegiolum) of theology’ as ‘destroying heresies and uprooting errors and planting the seeds of sacred doctrine’.

Bishop Thomas’s statutes set out in detail the constitution, administration and devotions of the college over 10 chapters. They also stipulate that all its members should come from the dioceses of Lincoln, York, and Wells. We will pursue the subsequent history of this community and its buildings next week.

Visit www.lincoln.ox.ac.uk

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher