Highland Retreats review: Proof that shooting lodges that aren’t all freezing monstrosities

A new book by Mary Miers, Country Life's fine arts and books editor, had Adam Nicolson gripped.

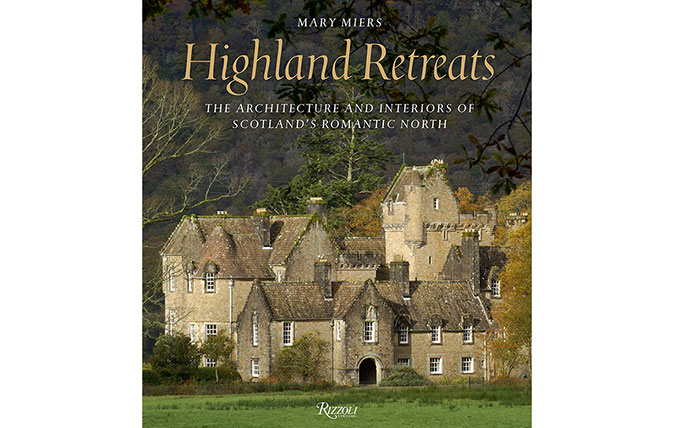

Highland Retreats: The Architecture and Interiors of Scotland's Romantic North, by Mary Miers, with photographs by Country Life Magazine, Paul Barker and Simon Jauncey (Rizzoli, £45)

Scholarly, original, witty and beautiful to look at; clear-headed about the whole phenomenon of the British rich colonising the Highlands and amazingly knowledgable; subtle and complex in its tracing of the various roots and variations of this love affair with a beautifully upholstered version of the wild; alert to absurdity; in love with the romance of it; perfectly designed by Robert Dalrymple and richly furnished with luscious and flattering photographs of the houses and their landscapes by Simon Jauncey and the late Paul Barker: what more could one ask from a book?

There is only one answer: nothing. All you need do, having absorbed the riches of Mary Miers’s pages, is go on the kind of assiduous tour she has clearly been embarked on for decades, visiting the astonishing buildings – or at least those that remain – whose flowering she has chronicled.

It’s easy enough to laugh at the great lumpen houses scattered across the Highlands, pretentious beyond belief, freezing, leaking, grey-souled, as pompous as a clutch of beadles at a banquet, imposing their plutocratic vulgarities on the serene landscapes around them, but this book turns all of that – or much of it anyway – on its head.

It all begins much earlier than you might expect, in the late 18th century, with a light and delicate version of the Picturesque, allied to a vision of freedom in the wild. This was the era of the ‘shooting cottage’, filled with pale fabrics and delicate furnishings, following the entrancing example of the Duchess of Gordon, who, from the 1770s onwards, allowed her children to run Rousseau-style barefoot around her lovely Speyside acres, while she danced of an evening with any man who would have her, at least if they promised to join up to fight the French. Only when they had agreed, would she pass them the golden guinea she held between her lips. It was all for her ‘a dramatick emancipation from the arms of society’.

The Victorian version loses some of that light-footedness. The great indoors became, all too often, a theatre of amazing extravagance and ridiculousness. Industrial and imperial money rolled north. Fortunes created from selling beer, whisky, textiles, gin, coal, Worcester sauce, steel, iron, bicycle seats, rifles, ships and cannon, opium, tea, railways, indigo, newspapers, finance, razorblades, bottling machinery and cotton poured into distant glens. By 1872, six separate architectural practices were operating in Inverness to cater to the gush of cash wanting to make the Highlands comfortable.

These holidaymakers brought not only their staff, but their hounds, their furniture, their portable fishing boats and their own food (including in one case a box of ‘pigs’ countenances’) with them. One English mine-owning family never came on its annual holiday to Scotland without a supply of coal transported by rail from its own collieries.

Shoals and herds of wild animals were sacrificed in service of this ideal, but the relationship between inside and outside was always a little agonised. At Victoria and Albert’s Balmoral – not the origin of the Highland love affair, but certainly giving it some oomph – thistles in the decor were ‘in such abundance that they would rejoice the heart of a donkey’ and the more tender visitors were likely to end up with frostbitten feet because the Queen insisted on keeping all the windows open during dinner.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Later sybarites were more sensible, installing fabulous Titanic-scale plumbing and heating systems behind the neo-Jacobean encrustations and Tudorbethan ceilings of their baronial haciendas. Baths were fitted with controls for douche, wave and spray, plunge sitz and jet. Hydroelectric turbine houses were equipped with marble-faced instrument panels. On some estates, the kennels wired up to the electricity before the estate cottages.

On the Isle of Rum, Sir George Bullough imported 250,000 tons of topsoil for the garden, kept hummingbirds in the camellia house and alligators and turtles in heated pools. The marble swimming pool at Skibo for the Carnegies could be converted to a ballroom by flooring over the heated seawater and installing a band in the gallery.

This is certainly one of the most brilliant social histories I have ever read. Behind it all, not unacknowledged, but not in the foreground, is the silent story of the Clearances ‘outside the scope of this book’.

Perhaps the author will bring her wonderfully clear eye and amazing energy to that other story next. It could, oddly enough, bear the same title.

Adam Nicolson

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin Published

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson Published

-

The 12 architecture books you should read in 2025, by our architectural editor John Goodall

The 12 architecture books you should read in 2025, by our architectural editor John GoodallJohn Goodall assembles a shortlist of his favourite architecture books published recently.

By John Goodall Published

-

How M.R. James wove country house architecture into his ghost stories

How M.R. James wove country house architecture into his ghost storiesIn his ghost stories, M. R. James had a perceptive eye for architectural detail, as Jeremy Musson explains and Matthew Rice evokes in specially commissioned drawings.

By Jeremy Musson Published

-

The 100 greatest cathedrals in Europe, as picked by Simon Jenkins

The 100 greatest cathedrals in Europe, as picked by Simon JenkinsSimon Jenkins gives himself a daunting task with his latest book, Europe's 100 Best Cathedrals (Viking, £30), which does no less than attempt to both explain and judge the masterpieces of western civilisation. Clive Aslet took a look and found a tome that will set readers 'afire to go on architectural pilgrimage'.

By Clive Aslet Published

-

The photographs (and photographers) who shaped the English country house style from the 1900s up to today

The photographs (and photographers) who shaped the English country house style from the 1900s up to todayTo coincide with the publication of his new book illustrated from the archives of Country Life, 'English House Style', John Goodall considers the long tradition of the magazine’s peerless interior photography.

By John Goodall Published

-

The vast and audacious architecture of London's greatest theatres

The vast and audacious architecture of London's greatest theatresRoger Bowdler takes a look at 'London’s Great Theatres', a new book by Simon Callow with photography from Derry Moore.

By Country Life Published

-

The latest update to Pevsner brings the 21st century update 'tantalisingly close to completion'

The latest update to Pevsner brings the 21st century update 'tantalisingly close to completion'The work of updating Nikolas Pevsner and Ian Nairn's magnum opus on the buildings of England continues with a volume focusing on West Sussex. John Goodall takes a look.

By John Goodall Published

-

The Country House Library: Why these rooms and their collections need to be taken much more seriously

The Country House Library: Why these rooms and their collections need to be taken much more seriouslyA new account of the country-house library will compel us all to reassess these rooms and their collections, says John Goodall.

By John Goodall Published

-

Britain's 100 best Railway Stations: Simon Jenkins on the gateways to our railways

Britain's 100 best Railway Stations: Simon Jenkins on the gateways to our railwaysThe latest book by Simon Jenkins looks at the 100 best railway stations in Britain. Gavin Stamp looks over the tome with his critical eye.

By Gavin Stamp Published