The architecture of Henry James: How real-life country houses found their way into the work of one of our greatest writers

The stories of Henry James are full of descriptions of country houses. Jeremy Musson explores the messages these houses convey, with the help of specially commissioned drawings by Matthew Rice.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In English Hours (1905), Henry James suggested that ‘the well-appointed, well-administered, well-filled country house’ was the only thing the English had ‘mastered completely in all its details’. Born in 1843 in New York, James had a cosmopolitan upbringing that included long periods in Europe. By his early thirties, he was living in Paris, before settling in England in the 1870s and becoming a naturalised British citizen in 1915, the year before his death. A successful, well-connected author, he had become an experienced country-house visitor.

He was not always impressed. After staying at Eggesford Manor, Devon, he observed in a letter to his father that: ‘The whole thing is dull... there is nothing in the house but pictures of horses — awfully bad ones at that.’

The country house was one of his favourite settings for novels and short stories and he often drew inspiration from the houses he had visited or knew. In The Lesson of the Master (1888), he describes ‘an old country-house near London’ with a long gallery that ‘marched across from end to end and seemed — with its bright colours, its high panelled window, its faded flowered chintzes, its quickly recognised portraits and pictures, the blue-and-white china of its cabinets and the attenuated festoons and rosettes of its ceiling — a cheerful upholstered avenue into that other century’. This is a reference to the Adam-designed gallery at Osterley Park, now in west London.

James also explored the essential experience and incidental details of the country-house weekend. In The Sacred Fount (1901), he captured the peculiar thrill of travelling by train to one and wondering who, of all the passengers boarding its carriages, might turn out to be fellow guests.

In an 1888 essay on London, he wrote of the pleasure of weekend escapes, arriving in ‘the hall of a country-house’ anticipating ‘the forms of closer friendliness, the prolonged talks, the familiarising walks which London excludes’. Indeed, long, intimate walks in the garden are a crucial element of the plot in The Sacred Fount.

In The Portrait of a Lady (1881), the opening pages contain a full and resonant description of Gardencourt (Fig 2), with its mellow red-brick manor house set in a lawn running down to the river. The portrait of this fine historic house was largely based on Hardwick House, Pangbourne, Berkshire, which James visited when it was owned by his cousin Charles Rose, a Liberal MP. This was first identified by scholar Bernard Richards (Country Life, October 29, 1981), based on his research on the unnamed photograph of Hardwick House, taken by Alvin Langdon Coburn for the frontispiece of the New York edition of James’s collected works (1906–09).

The Portrait of a Lady begins with the picture of an English idyll for, as he writes: ‘Under certain circumstances there are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea.’ In this case, the ‘implements of the little feast’ have been ‘disposed upon the lawn of an old English country-house, in what I should call the perfect middle of a splendid summer afternoon’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The house is set on a low hill, with a ‘long-gabled front of red brick, with the complexion of which time and the weather had played all sorts of pictorial tricks, only, however, to improve and refine it’. It creaks with history, having been ‘built under Edward the Sixth’ and having ‘offered a night’s hospitality to the great Elizabeth’, whose ‘huge, magnificent and terribly angular bed’ is the great honour of the sleeping apartments. After being ‘bruised and defaced in Cromwell’s wars’, enlarged during the Restoration and ‘remodelled and disfigured in the eighteenth century’ the house is now in ‘the careful keeping of a shrewd American banker’.

The banker, Mr Touchett, had bought the house as a great bargain, but ‘with much grumbling at its ugliness, its antiquity, its incommodity’. But after 20 years, he had developed ‘a real aesthetic passion’ and knew all its points and ‘would tell you just where to stand to see them in combination and just the hour when the shadows of its various protuberances which fell so softly upon the warm, weary brickwork — were of the right measure’. The lady of the title is Isabel Archer, his visiting niece, who meets the amiable Lord Warburton, ‘a real English lord’, at that very tea party on that sunlit lawn. A little later, she visits his ancient family seat, Lockleigh, only lightly sketched in, with its ‘vast drawing room (she perceived afterwards it was one of several), in a wilderness of faded chintz’.

In The Portrait of a Lady, the ownership of the house is central to James’s description, but in The Princess Casamassima (1886) he plays on the effervescent grandeur of rented country houses. Here, the beautiful American-born princess of the title is visited by a young bookbinder of radical political persuasion, at a house called Medley, which ‘was not hers, but only hired for three months, and it could flatter no princely pride that he should be struck with it’. Yet ‘he finds something in the way the grey walls rose from the green lawn that brought tears to his eyes’ and is struck by the novelty of its long duration being ‘unassociated with some sordid infirmity or poverty’, so that its majestic preservation has ‘a kind of serenity of success, an accumulation of dignity and honour’.

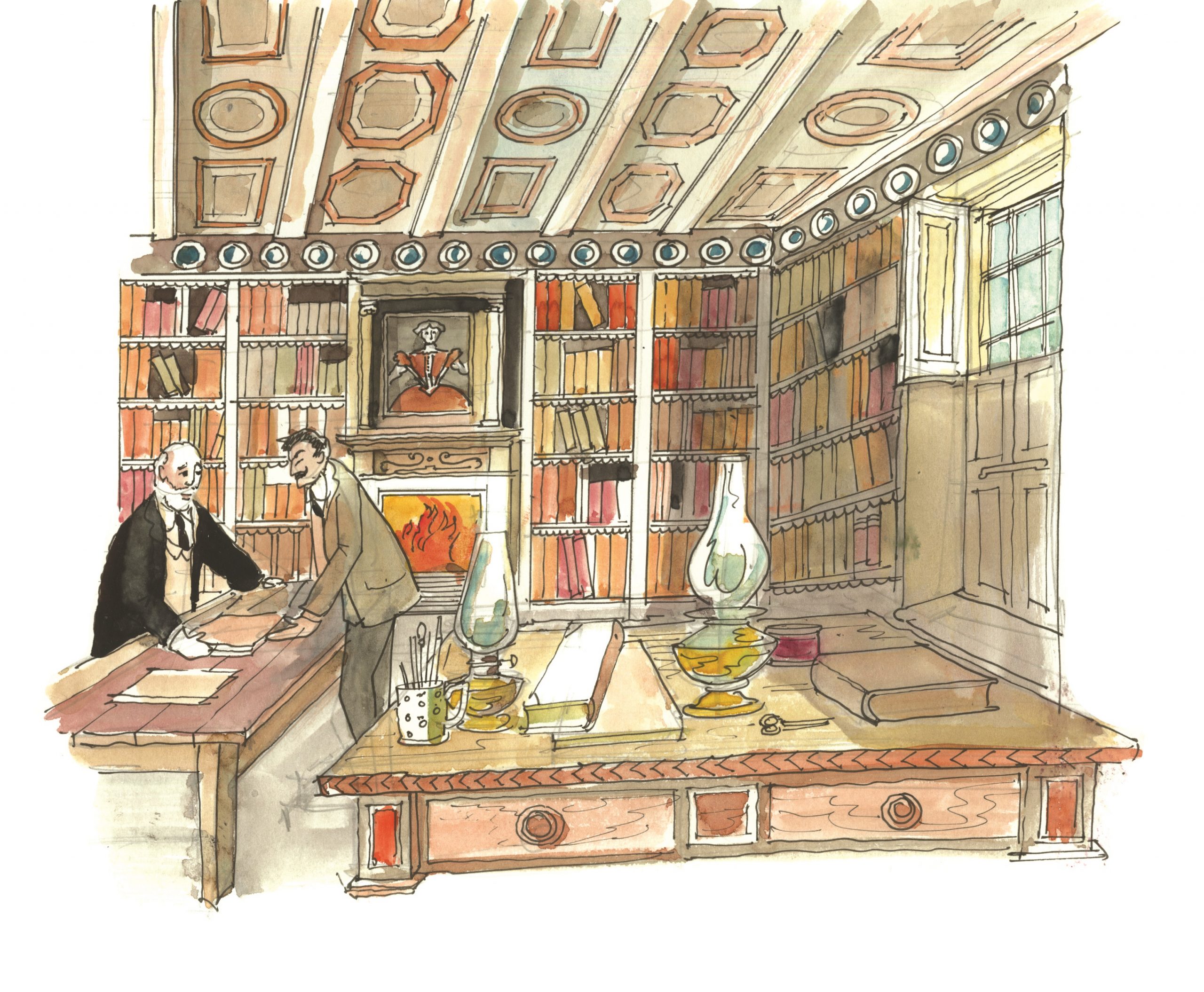

After being served a grand solitary breakfast by a footman, the bookbinder is escorted by the butler to ‘an old brown room, of great extent — even the ceiling was brown, though there were figures in it dimly gilt — where row upon row of finely lettered backs returned his discriminating professional gaze’ (Fig 4). The library has a crackling fire, alcoves ‘with deep window-seats’ and its luxurious, leather-covered armchairs feature ‘an adjustment for holding one’s volume’, a luxury that also stirs the young revolutionary bookbinder.

The James novel most focused around a fine country house is The Spoils of Poynton (first published as a serial in 1896). Poynton is the name of a manor house that was possibly a scaled-down version of Montacute in Somerset, which James visited in 1881 and especially admired (Fig 3). Poynton, we learn, is early Jacobean; an ‘exquisite old house’ that is ‘supreme in every part’, a description that captures an attitude enhanced by aesthetic movement values: the ancient and historic was admired far above stately Palladian or over-assertive Gothic Revival. These were also the early years of Morris and Webb’s Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

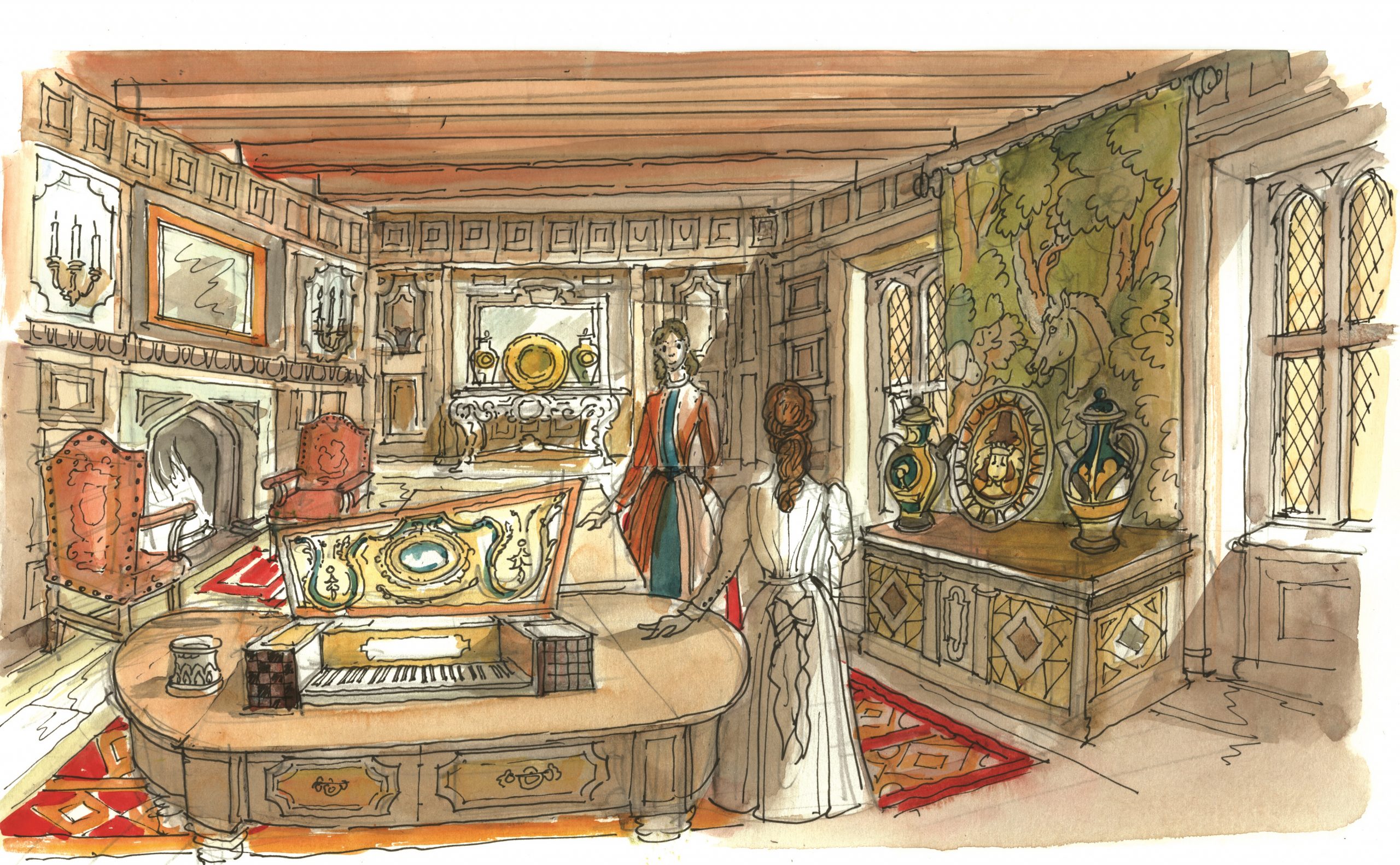

The interiors of Poynton include rooms of fine panelling, oak floors, Italian brocade wall-hangings and cabinets filled with beautiful things collected by Mr and Mrs Gereth (Fig 5). After the death of her husband, Mrs Gereth has to hand all to her son. She remains in residence, however, until the son prepares to marry. To her horror, the house of his prospective father-in-law is called Waterbath and possessed of ‘an ugliness fundamental and systematic’ and ‘smothered with trumpery ornament and scrapbook art’. Dr Richards has identified a likely model for the ‘hideous’ Waterbath, too, in Foxwarren Park, Surrey, a gabled 1850s red-brick house designed by the gentleman amateur Charles Buxton with help from Frederick Barnes — the latter better known for railway stations.

For this legendary battle of aesthetics, James was inspired by a real court case, Ross versus Ross, involving the Lockhart Ross family at Balnagown Castle in the Scottish Highlands, where a widowed mother moved to a dower house illegally taking the finest treasures with her. Much of the story is conveyed in conversations between Mrs Gereth and her young friend Fleda, who shares her distaste for Waterbath. Waterbath’s ‘long and bland’ vistas reveal to her that Poynton is, by contrast ‘the record of a life’, one ‘written in great syllables of colour and form’ by the ‘tongues of other countries and the hands of rare artists’. Although the interiors are ‘all France and Italy’, when you look through its old windows, ‘it was England that was the wide embrace’.

James commissioned a photograph from Langdon Coburn for the frontispiece for the New York edition of the novel, in this case, an interior detail of the Wallace Collection in Hertford Square. He perhaps drew on its atmosphere and treasures for Poynton’s artistic interiors, where, instead of paintings, ‘the panels and the stuffs were themselves the picture; and in all the great wainscoted house there was not an inch of pasted paper’.

The Turn of the Screw (1898) is James’s most chilling and perennially popular work, a novella set in a remote house called Bly (Fig 1). The unnamed narrator is a young governess sent to take charge of two children, supported by resident staff, but with an absent employer. She remembers a pleasant first impression of a ‘broad, clear front, its open windows and fresh curtains and the pair of maids looking out’ and notes ‘the lawn and the bright flowers’ and the ‘treetops over which the rooks circled and cawed in the golden sky’. It is all very different to ‘her own scant home’.

A tower is described as one of a pair of ‘square, incongruous, crenellated structures’, which stand at opposite ends of the house and are distinguished from each other as ‘the new and the old’. The governess sees them as ‘architectural absurdities’, redeemed by ‘not being wholly disengaged nor of a height too pretentious’. She places their ‘gingerbread antiquity’ in a period of romantic revival ‘that was already a respectable past’. She admires them and has fancies about them, ‘especially when they loomed through the dusk’, struck by ‘the grandeur of their actual battlements’.

There are clear echoes of Jane Eyre in The Turn of the Screw and it is a narrative where the remoteness, solidity and potential for the ‘Gothic’ horror of the house itself is artfully contrived to add anxiety and even confusion as the tale unfolds. The Turn of the Screw has an intensity and directness that has lent itself to many dramatic interpretations.

Although a regular visitor to country houses, James never acquired one of his own. When he sought a retreat, in 1897, he took the lease on the red-brick, early-Georgian Lamb House in the small town of Rye, East Sussex (Country Life, July 18, 2012). His friend Edward Warren, an architect, helped him gently remodel the house. Professing ignorance of gardens, James leaned on the advice of Alfred Parsons and the garden setting of Lamb House is enshrined in the garden of Mr Longdon in The Awkward Age (1899). Mr Longdon’s house is ‘old, square, red-roofed, well assured of its right to the place it took up in the world’ (Fig 6). Its garden’s greatest wonder is ‘the extent and colour of its old brick wall, of which the pink and purple surface was the fruit of the mild ages and protective function’. In August, it thrills to ‘the bliss of birds, the hum of little lives unseen and the flicker of white butterflies’.

Here, as in other portraits, James recognises the power of ownership, so the house has, ‘the look of possession’ everywhere about it, ‘in the form of old windows and doors, the tone of the old red surfaces, the style of the old white facings, the age of the old high creepers, the long confirmation of time’. It was ‘suggestive of panelled rooms, of precious mahogany, of portraits of women dead, of coloured china glimmering through glass doors and delicate silver reflected on bared tables’. In this most English of descriptions, of a kind of country house in a town, James shows us a picture of the house and tradition he loved.

Acknowledgements: Philip Horne, Bernard Richards

Are these the seven best independent bookshops in Britain? A writer makes her case

My favourite painting: Gavin Plumley

Gavin Plumley, author and cultural historian, selects an unusual canvas with two painters credited.

The engineering genius of Britain's great Victorian glasshouses — and how many are in a battle to avoid 'The Spiral of Doom'

Whimsical and ethereal, as well as feats of engineering, Victorian glasshouses are a reminder of pioneering progress and deserve sensitive