Gustavus III: The designs of the king who dreamed he was an architect

Many monarchs of the Enlightenment showed an active interest in architecture. Inspired by a new facsimile of royal drawings from Sweden, Clive Aslet looks at the designs of Gustavus III.

In 1779, Gustavus III of Sweden commissioned a painting from Pehr Hilleström called Conversation at Drottningholm Palace. It shows the King and his court in one of the à la mode neo-Classical rooms of Drottningholm Palace, outside Stockholm, lit by tall sash windows draped with the lightest of translucent fabrics. The ladies, busily employed at their needlework, listen to a man reading from a book as Gustavus, seated at a desk, gazes upwards, as if for inspiration. His pencil hovers over some architectural drawings on his desk. They relate to a visit he had recently paid to his cousin Catherine the Great of Russia. As he wrote to her describing the painting (Fig 1): ‘I am sitting on a sofa, drawing, and I am reviewing numerous plans, including one of Tsarskoe Selo where I am looking at the places where I strolled with the mistress of this beautiful place.’ He was reliving the trip through the buildings he had seen. Architecture was a passion.

From Ancient Egypt onwards, building monuments and palaces has always been a kingly activity. In Renaissance Italy, the Humanist author Baldassare Castiglione laid particular emphasis on the need for a great ruler to be remembered through the architectural achievements of his reign. The idea held. Every Baroque monarch wanted to follow the example of Louis XIV, for whom gloire blazed through the châteauand gardens of Versailles, not to mention the Grand Trianon, the palace of his mistress Madame de Montespan at Clagny, the military hospital of Les Invalides and numerous fortifications by Vauban. Louis loved to immerse himself in the creative process, taking a minute interest in his projects and personally approving drawings even when on campaign. In this respect, Gustavus was another Sun King, albeit without matching resources. He collaborated closely with his architects, whether or not he was holding the pencil himself.

In Britain, the future George III was taught architectural drawing by Sir William Chambers, a Swede of English descent whose title was that of a Swedish order, Knight of the Polar Star. Nobody, however, considers that George III was particularly skilled as a draughtsman, the drawings that survive in his hand having probably been improved by others. Certainly none were realised.

In this, Gustavus III did better than his English contemporary: not only were his drawings more accomplished but at least some of them came to fruition as buildings. Unlike Frederick the Great of Prussia or our own George IV, whose excited engagement with the visual arts was limited to collecting, commissioning and connoisseurship, Gustavus can genuinely be considered an architect. There are few, if any, other European monarchs of whom this might be said, except possibly his royal father, Adolf Frederick.

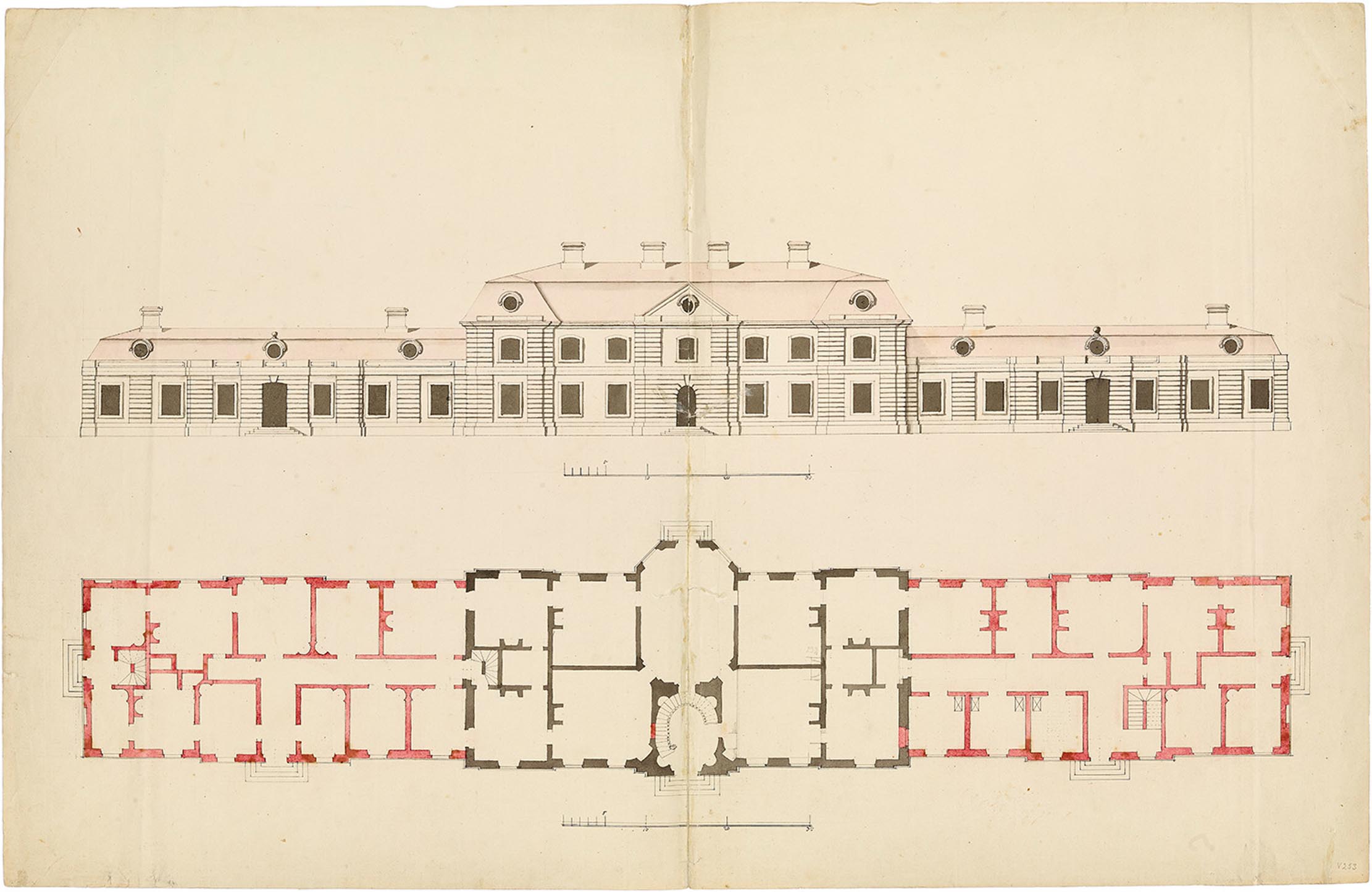

Little of Gustavus’s oeuvre now survives, which makes it all the more fortunate that a collection of 472 drawings largely owned by him (known, from the family name of the old Swedish royal house, as the Vasa Collection) has come down to us. As well as works by court architects from the 17th century onwards, it includes many drawings by Adolf Frederick and no fewer than 190 by Gustavus. Some are façades for palaces in different styles (Fig 5), many are for gardens and theatrical entertainments, others for relatively humdrum alterations to royal residences for which there was presumably a practical need.

The collection’s survival indicates the emotional importance that it held for Gustavus’s son Gustavus IV Adolf: when a coup forced him from the throne in 1809, he took the drawings with him into exile in Germany. There they remained until, amid the chaos of the Weimar Republic, the Vasa Collection was sold to a dealer. Returned to Sweden for an exhibition in 1924, it failed to excite the interest of the Swedish state, but was bought, from patriotic motives, by Helge and Axel Ax:son Johnson.

This year, the Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation for Public Benefit has made it more widely accessible by publishing a facsimile with Stolpe Books. The facsimile itself is a major undertaking, as one of the drawings is 6ft long. So splendid is this production that Francis Terry has designed a special cabinet to contain it. Of the six that have so far been made, one has been generously donated to the Travellers Club.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Architecture was only one of Gustavus III’s accomplishments. As well as being an adventurous statesman and determined social reformer, who, in the words of a 19th-century biographer, sought to ‘change the customs and almost the character of his people,’ he shone as a patron—and practitioner—of the Arts. Music and theatre were paramount. According to his entry in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, he began writing librettos and dramas at the age of 10.

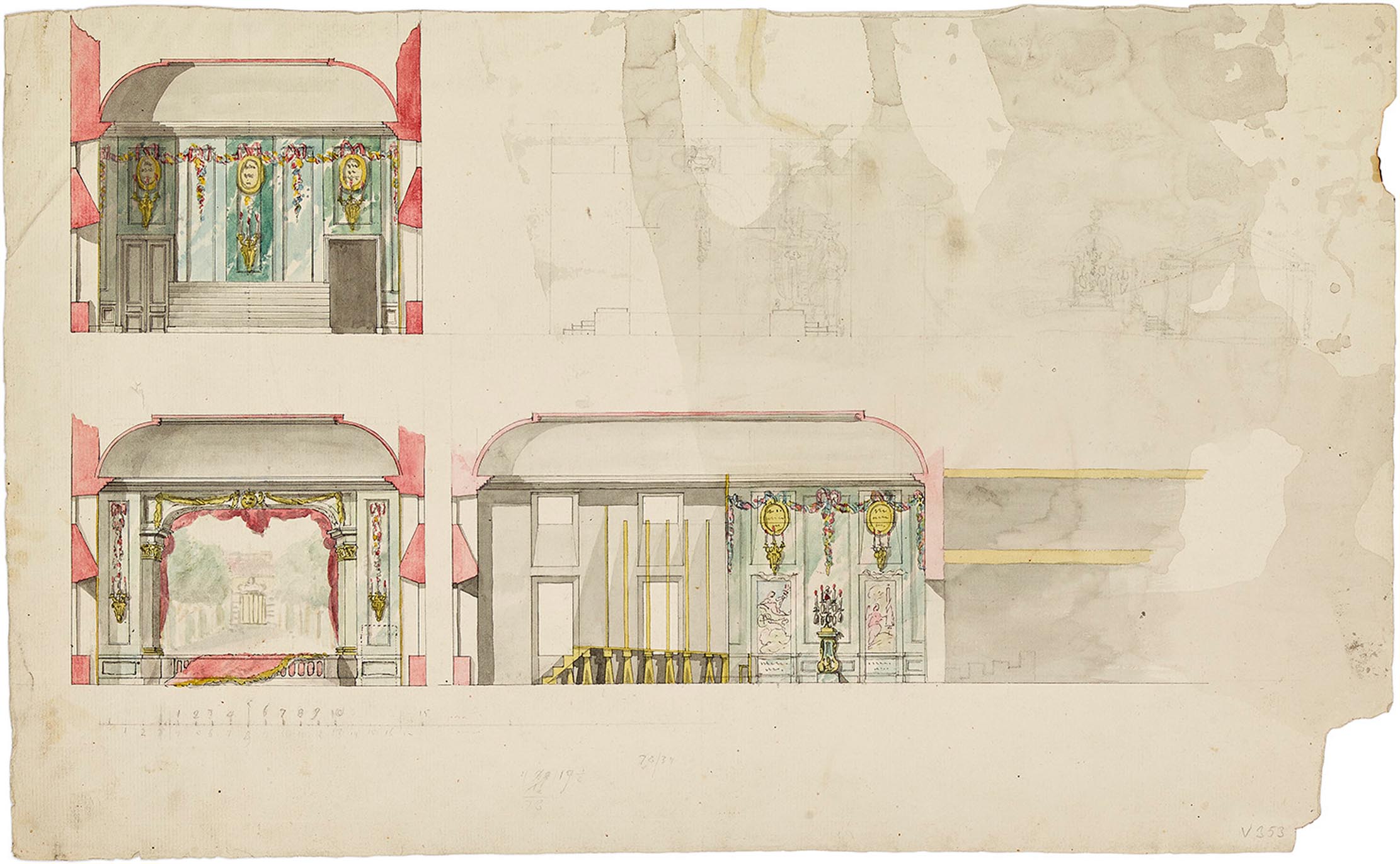

Gustavus’s love of drama had been stimulated by a liberal early education directed by Count Tessin, who was himself a born actor. The young prince, who became known as the Theatre King, was given engravings to look at, as Tessin acted out the different crafts and machinery he was studying. Aptly, Gustavus was at the theatre when he heard he had become King in 1771. He was also at the theatre when he was assassinated in 1792—the bullet that killed him was fired during a masquerade at the Opera House he had founded. As a crowning symmetry, the episode also became the inspiration for Verdi’s opera A Masked Ball. One drawing in the collection (Fig 6) shows a theatre Gustavus designed for Ekolsund Palace that was never built; happily, the Gustavian theatre at Drottningholm—the setting for Ingmar Bergman’s 1975 film of The Magic Flute—has been revived for opera performances.

Under Gustavus, Sweden developed its own version of French neo-Classicism, softened through the use of trompe l’oeil to replace costly materials. This reflected the cosmopolitan outlook of an Enlightenment monarch, who banned torture, granted press freedom, accorded religious toleration and promoted free trade—but was, nevertheless, as much an autocrat as Louis XIV. Personal authority allowed him not only to found the Swedish Academy, but to impose his stamp on the public buildings erected during his reign, all of which required his approval.

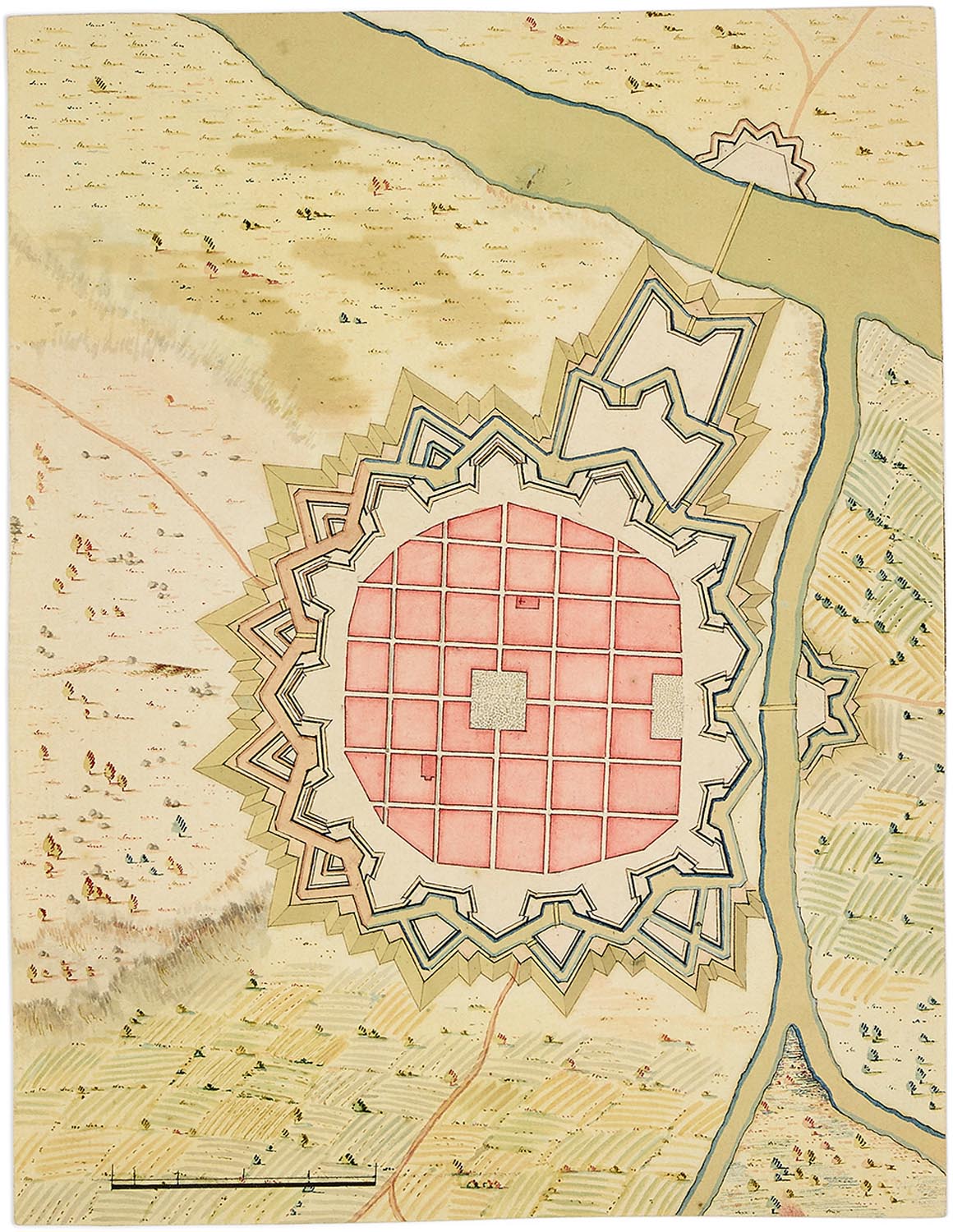

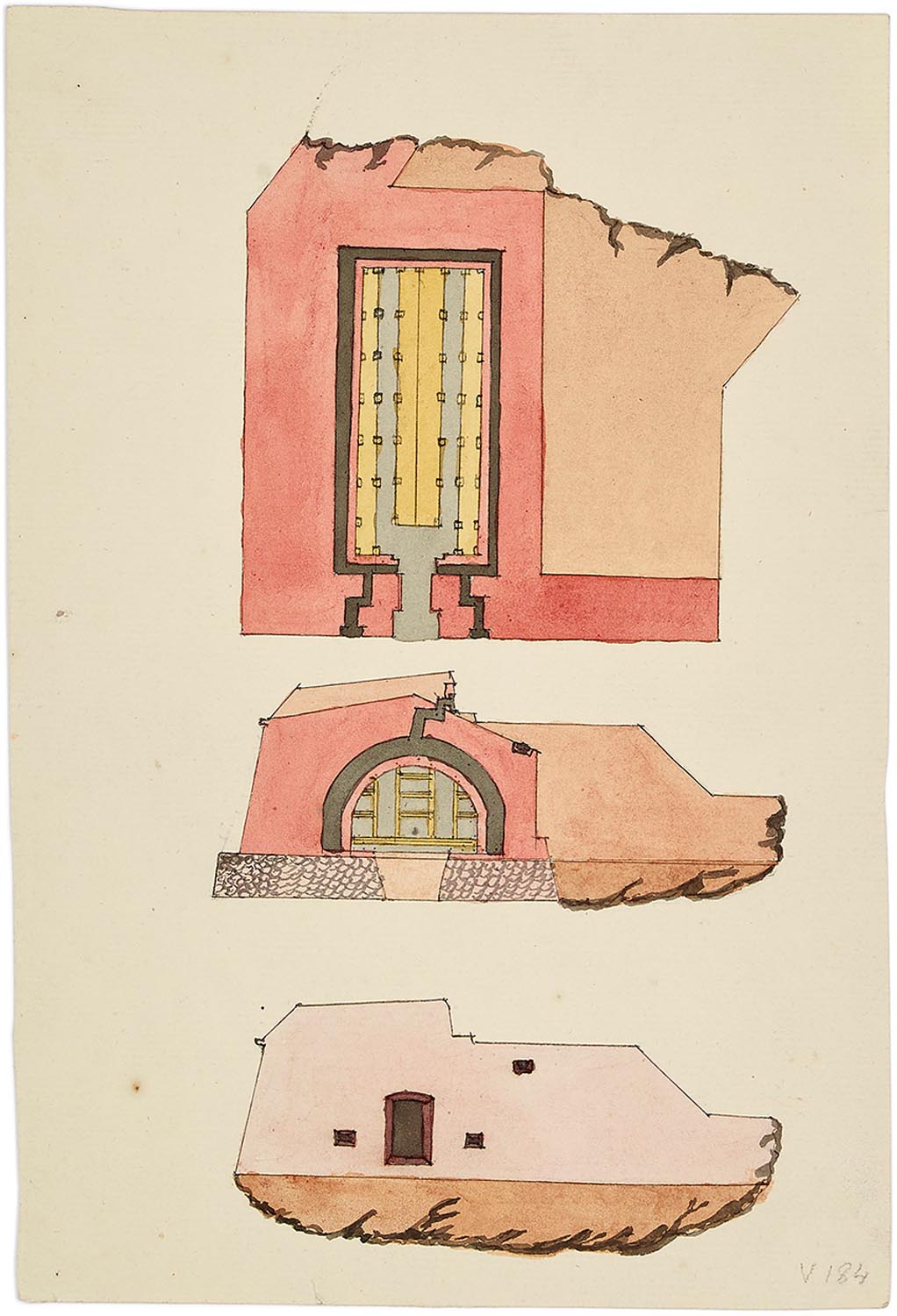

Architecture had a military aspect in the form of fortification; this Gustavus was taught as a boy. A somewhat naïve plan for a fortified town (Fig 2) may date from these years, showing, as may a more detailed exercise, a design for a gunpowder magazine under a ravelin (Fig 7). Given his father’s interest in architectural drawing, which he preferred to kingship, it is not surprising that architecture also featured on Gustavus’s personal curriculum. Lessons were given by the court architect Jean Eric Rehn, remembered for the library at Drottningholm, whose light neo-Classicism prefigures the Gustavian style. Although some of Gustavus’s early drawings betray the clumsiness of a student, by the time he was in his twenties, his game had been raised. The Crown Prince, as Magnus Olausson points out in The Collection of Gustavus III (Stolpe, 2021), dreamt of rebuilding the palaces he could use at Ekolsund and Karlberg, under the influence of Versailles.

These were not mere fantasies: in the early 1770s, he proposed extending Ulriksdal Palace with the addition of an attic storey—a pragmatic idea, albeit never executed. The memorial in the form of a pantheon reveals Gustavus’s interest in the more doctrinaire aspects of French neo-Classicism, with its emphasis on ideal forms and colonnades.

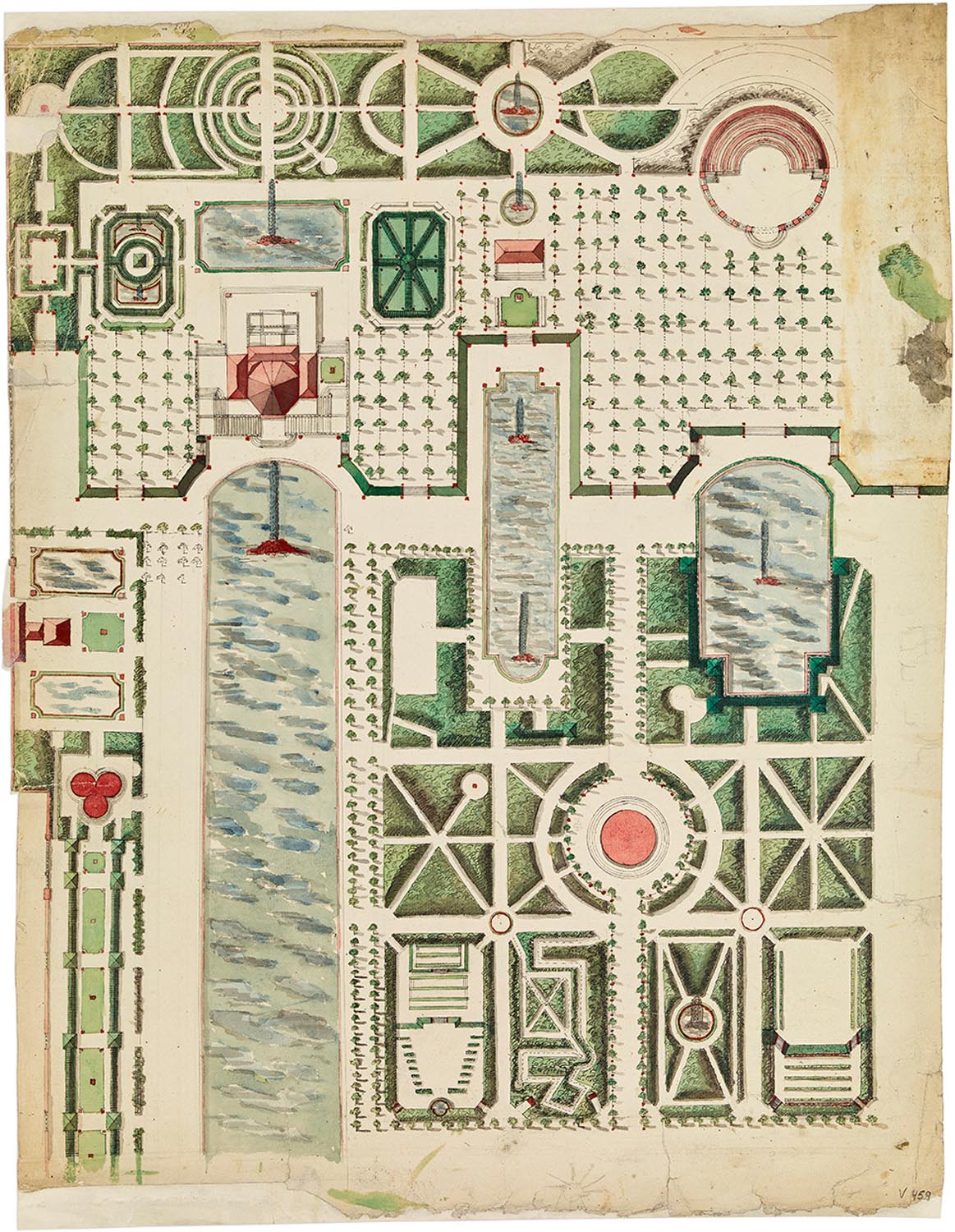

There are designs for gardens in the Vasa Collection, too (Fig 8). Gardening was a major and often expensive preoccupation of European monarchs and landowners in the 18th century and fashions changed quickly. At Drottningholm, we see Gustavus developing his own ideas—and it was undoubtedly a mistake for the architect Fredrik Piper to try to improve on them. Piper tried to do this by redrawing Gustavus’s designs in a more informal style, influenced by the jardin anglais of France. He found himself dropped from the Drottningholm project and given responsibility only for the palace at Haga. Although the King called the new park at Drottningholm an English garden, his preference for the retention of formal elements was reinforced by a visit he paid to Rome, supposedly incognito, but with an entourage of 20, in 1783.

‘Here I see a thousand things I could plan into my garden but which I am bound to forget if I do not draw them,’ he wrote after only a week in the city. He sent impatiently for the working drawing of the Drottningholm garden, so he could continue work on it.

Meanwhile, he bought ancient sculptures and designed a Parnassus. At last, after three months, Gustavus’s drawing arrived and he spent a feverish week on it, taking inspiration from buildings he had recently seen, such as the Villa Pamphili. ‘The design itself has got a little cluttered from all the small changes I have made,’ he told a courtier, ‘though it is clear enough that I believe it can serve for the head gardener.’

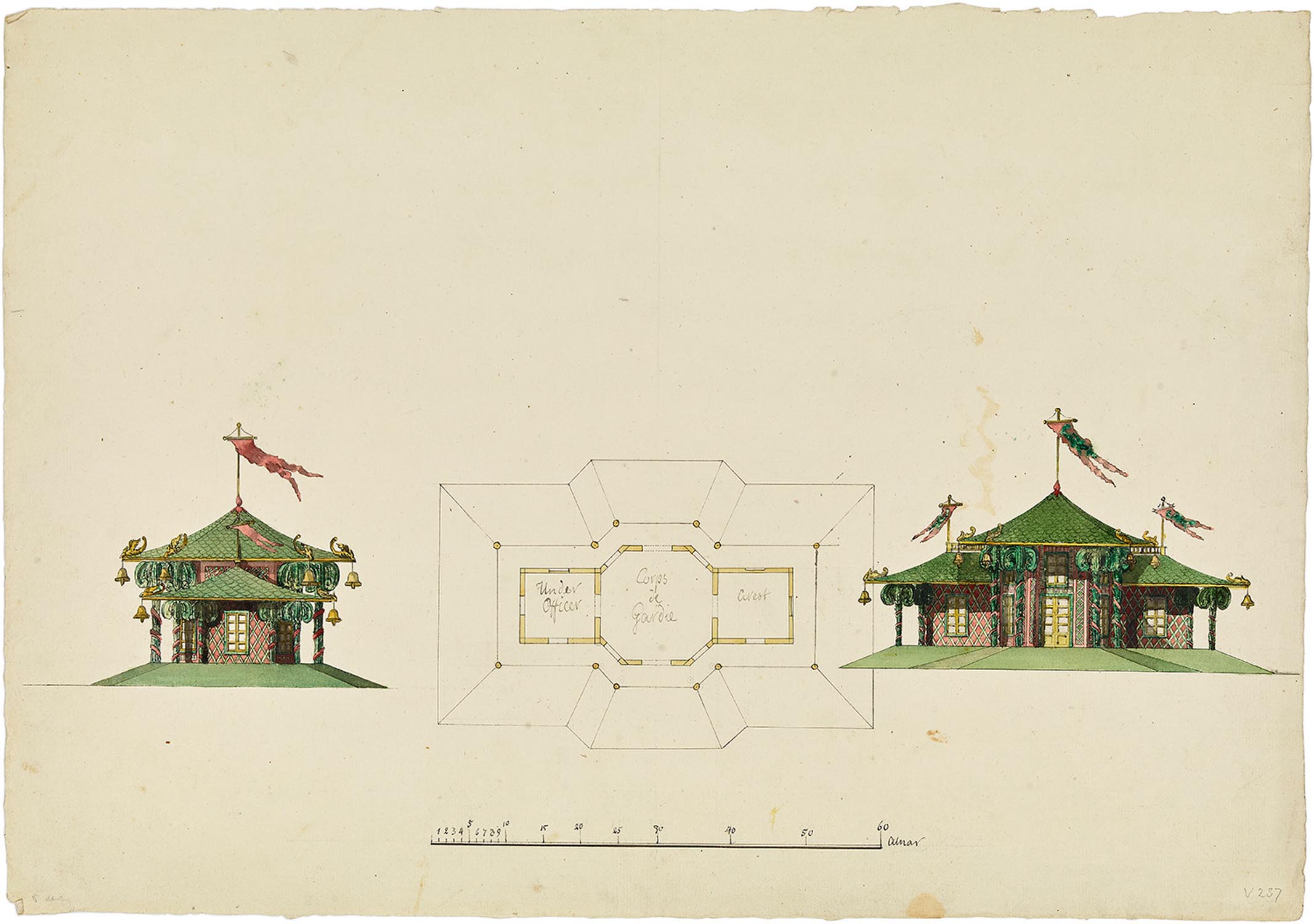

With gardens went garden buildings and Gustavus was particularly attracted to the Chinoiserie style of the Chinese pavilion erected for Gustavus’s mother, Queen Lovisa Ulrika. This had a special place in his affections as one of the scenes of his childhood. The pavilion itself, built of wood, had been replaced, but some of the buildings nearby had become derelict.

On becoming King, Gustavus designed a Chinoiserie guard house (Fig 4); a few years later, he dropped the scheme in favour of a Turkish or Roman tent commissioned from the architect Carl Adelcrantz.

Across Europe, the richest of the rich spent large sums on the décor for entertainments, the extravagance of the setting seeming all the more striking for its purely temporary nature. Gustavus delighted in such ephemeral works. In the late 1760s, he devised a neo-Classical scheme, with urns, swags and rich drapery, to honour his long-suffering wife, Sofia Magdalena. Tournaments or carousels—a cross between a court masque, a French ballet and a stylised battle scene—were a favourite entertainment of the Swedish court and Gustavus delighted in the design of staging and costumes. Another one depicts a royal stand designed for a tournament held at Ekolsund in 1776.

In August 1785, when almost the whole court took part in a carousel called L’Entreprise de la Forêt enchantée at Drottningholm, as Magnus Olausson observes, the King was ‘as involved as the scenographer and architect Louis Jean Desprez in all the preparations for costumes and backcloths’.

There is a drawing in his hand for a sultan’s turban, for a part played by Count Sten Lewenhaupt, and his helmet for a Persian prince, played by Count Magnus Stenbock (Fig 3). Count Gustaf Wachtmeister, a lieutenant-colonel, was called to the palace to play the King of India, dressed in a crown surmounted by feathers: it can hardly be condemned as an example of cultural appropriation, being so far removed from anything actually worn in the subcontinent.

How delightful these carousels, staged by Gustavus, must have been. In the Vasa Collection, we see this most charming and cultivated of monarchs in his most radiant light.

Island hopping in Sweden: 'Pine forests, cobalt rivers and toy-town villages of scarlet wooden cottages'

Sweden has more than 30,000 islands to take in, and many of them are easily accessible from the capital, Stockholm.