Great Chalfield Manor: How this medieval house was loved back to life

In the second of two articles, Clive Aslet reveals how this medieval manor house was loved back to life by an Edwardian engineer, Robert Fuller, and his scholarly architect, Sir Harold Brakspear.

It was the very eve of the First World War when Country Life last visited Great Chalfield in Wiltshire: August 15 and 29, 1914. Hardly could a better house have been chosen for that momentous time, as the photographs show a 15th-century manor that looks dreamily immemorial, although the reality, as H. Avray Tipping explained, was rather different.

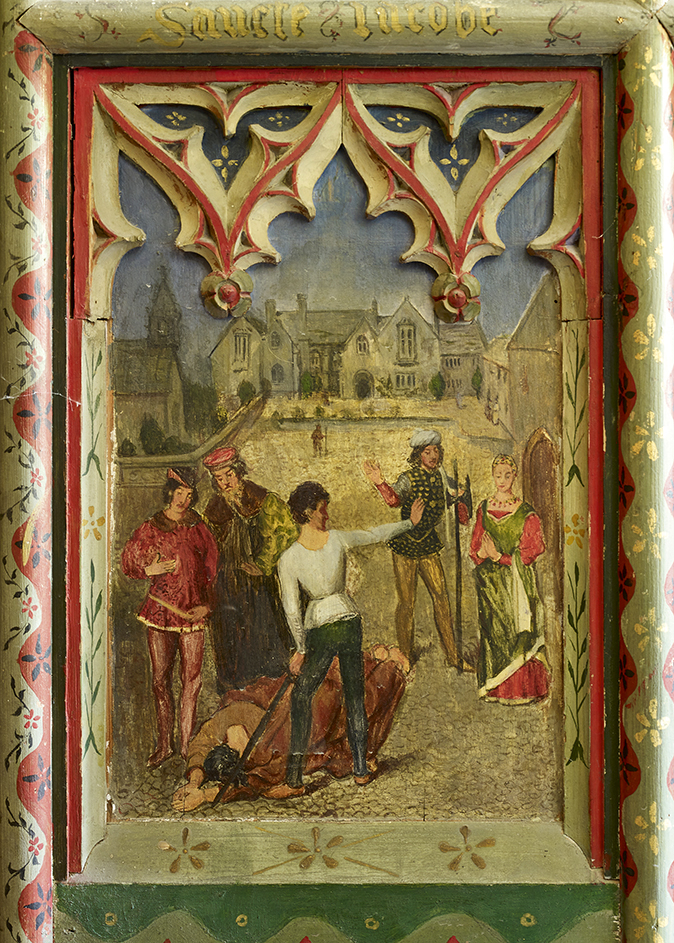

Great Chalfield had just been through a major restoration under the hands of the owner Robert Fuller and the architect Sir Harold Brakspear, with another architect, C. H. Biddulph-Pinchard, still at work on the back. It says much for both the scholarship and the visual sensitivity of these men that the spell in which this sleeping beauty had been wrapped since Great Chalfield’s decline as a gentleman’s seat was not broken.

That decline set in early. Little of architectural consequence happened at Great Chalfield after the 17th century, beyond the arrival of increasing numbers of water-colourists and antiquaries. Interest was quickened by the appointment of the Rev Richard Warner as rector of the little parish church. He was an antiquarian whose circle included John Buckler. His son and namesake, J. C. Buckler, made six watercolour drawings of Great Chalfield in 1823 and, in 1836, T. L. Walker, a pupil of A. C. Pugin, also produced a detailed survey volume on the house, published in 1837 as his Third Series on Gothic Architecture.

All this work was commissioned by the then owner of the house, Sir Harry Burrard-Neale, a retired admiral, who, although living in Hampshire, probably intended to restore the property. Sir Harry, however, already over 70, did not live to complete this project. Instead, disaster followed his death in 1840. Far from being sympathetically restored, the house was mauled by the then tenant. The hall was divided by a floor and the entire Great Chamber range behind the north-east gable façade was demolished. The service wing at the back of the house had already gone.

Despite this mistreatment, Great Chalfield fared better than some other manor houses. East Barsham Manor in Norfolk, for example, was reduced to little more than a façade. Old, inconvenient and - to Georgian and Victorian eyes - dark manor houses did not usually make suitable seats and yet, because of the workings of the entail system that restricted the sales that could be made from landed estates, they could not be sold. Those not subject to entail, like Great Chalfield, often changed hands frequently.

As a result, houses of the kind that Thomas Hardy enshrined as Wellbridge House (based on Woolbridge Manor) in Tess of the d’Urbervilles - once a ‘fine manorial residence but since its partial demolition a farmhouse’ - were a common sight, particularly in the west of England.

A change in fortune came at the end of the 19th century. Reform of the entail system through the Settled Land Acts of the 1880s coincided with a rise in the appreciation of ancient, smaller country houses, particularly by the Arts-and-Crafts movement; to William Morris, Kelmscott Manor, his home in Oxfordshire, was a domestic ideal. Great Chalfield joined the ranks of a growing number of romantically restored manor houses.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This was very much the taste of the early Country Life, as Jeremy Musson has described in The English Manor House (1999), and the fledgling National Trust.

The Prince Charming who kissed Great Chalfield awake was Robert Fuller. His father, George Pargiter Fuller, Liberal MP for Wiltshire West, lived at Neston Park, coincidentally the principal seat of Great Chalfield’s 15th-century builder, Thomas Tropnell. From his father, John Fuller, he had inherited a share in Fuller, Smith & Turner, the brewery.

In 1864, he married Emily, the daughter of the baronet Sir Michael Hicks Beach. G. P. Fuller bought Great Chalfield in 1878 for its farmland; it seems that he contemplated demolishing more of the house, which was again in a bad way. An improving paternalist, he used the spring at Great Chalfield to provide a water supply to the neighbouring villages.

Demolition would have appalled Philip Webb, Secretary of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), who, in a letter of 1881 to his friend George Boyce, had been sufficiently alarmed to hear that ‘an archaeological society… has been advising Mr Fuller to “restore” some painting (decorative) which remains at Great Chaldfield [sic]’ - presumably the wall paintings in the church (the wall painting in the house was, as yet, unknown).

G. P. Fuller was dissuaded from his course of destruction by Robert, his fourth son. Although Robert’s eldest brother, John, educated at Winchester and Christ Church, Oxford, followed his father into politics, becoming an MP, baronet and the Governor of Victoria, Robert pursued what, for a son of a landed family, was a less conventional course: he trained as an electrical engineer, winning a gold medal from Faraday House in 1896.

The following year, he became works manager of a concern that his father had bought in Melksham: Avon Rubber. At the dawn of the motor age, this made solid tyres as well as conveyor belts and railway components. Pneumatic tyres, at first for bicycles, came in 1900 and, by the First World War, golfballs had become a successful line (this business would soon be sold to Dunlop).

Still a bachelor, one of Robert’s pleasures was fishing, which he pursued at Great Chalfield. It was this that introduced him to the house and he fell in love with it. He persuaded his father to let him revive it.

The architect chosen for this project was Sir Harold Brakspear, who lived at Corsham in Wiltshire. Research by Paul Jack for a postgraduate dissertation for Oxford University reveals that Brakspear’s father, Thomas Hayward Brakspear, had been a pupil of Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament. This had made the elder Brakspear into an enthusiastic Goth, who instilled a love of monastic architecture in his son.

However, having married his late wife’s sister, against the law of the time, T. H. Brakspear had been forced to leave his home in Manchester: that explains both the family’s presence in a sleepy Wiltshire town and Harold’s lack of formal education. However, neither obstacle deterred Harold, born in 1870, from a career tending old buildings. These included Jaggards, a medieval house rebuilt in the 17th century, owned by G. P. Fuller near Corsham.

By the time Brakspear bicycled over (one hopes on Avon Rubber tyres) to make his first survey drawings of Great Chalfield in the winter of 1903, he was already at work on Lacock Abbey and very busy.

After the First World War, Brakspear would embark on his greatest projects, the restorations of Haddon Hall and St George’s Chapel, Windsor. When he began on Great Chalfield, however, he was, although only 33, already an architect of considerable experience and proven scholarship. This did not deter Robert Fuller, his junior by five years, from having his own views on every detail of the project. His papers, held, along with 200 of Brakspear’s drawings, at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre at Chippenham, contain draft letters in pencil, covered in elaborations in ink and lists of queries to be raised with the architect in person.

Naturally, money was a consideration, but both men were driven by a desire to do their best by the house. Although Brakspear was scrupulous in distinguishing his work from the original by the use of a yellower-coloured stone (according to best SPAB practice), it is not always easy to detect what he did, after more than a century of weathering. The drawings, however, show that he did a great deal, even in the surviving west wing.

Generally, it was fortunate that the house had been so fully recorded in the early 19th century. This, however, could be a source of tension between the architect and his client, as the latter wanted as much fidelity to original details as possible.

It led to a long and agonised discussion over the rebuilding of the lost east wing. Fuller demanded that the window details in the new east wall were copied from the existing fabric - and got his way. Brakspear argued for as much symmetry as practicable in the arrangement of the openings - and got his way.

The ground floor of this wing comprised, eventually, a smoking room and library. The keystones to the old ground-floor vault were found in the garden and some of an Elizabethan fireplace in a rockery: this enabled the reimagining of the fireplace on the first floor of the east wing, in what Brakspear called the drawing room.

Walker had shown that the old drawing room roof was very similar, but not identical, to that of the matching room in the west wing. There was, for some time, a stand-off between architect and client as to the detail of the new work, Brakspear patiently observing that Fuller’s assumptions as to the original forms were not always correct. As a result, the rebuilding of the wing took five years.

Neither client nor architect was slavish in following SPAB principles. Initially, Fuller hoped to retain 15th-century woodwork for a new screen in the great hall, but only on grounds of cost - it was decided to have it recarved by Rudman in ‘best dry wainscot oak’ for £107. Brakspear wanted to introduce glass panels to reduce the gloom, but was overruled. He was dealing not only with an architectural enthusiast, but an engineer, who took a detailed interest in steps, stables, pipes, gutters, timber details, the ventilation of waterclosets and the insertion of a bath into an ancient chest.

The stables and motor house were particularly close to Fuller’s heart; the latter required a fitting room with a forge, as spare parts did not come ready made.

In 1907, Fuller commissioned the artist and gardener Alfred Parsons to design the garden. Parsons, an early member of SPAB who had helped to found the Art Worker’s Guild, was a thorough Arts-and-Crafts man, who would have been interested in the restoration of the manor house. He created a scheme of dry-stone walls and paved walks: pairs of yews either side of one path have now grown into ‘houses’. Fuller rejected an Italianate fountain, wanting ‘to stick to purely British as far as possible’. Planting began in 1910 to a budget of £100. The scheme is still essentially what is now superbly gardened by Patsy Floyd and her team.

Eight years after Brakspear first discussed the project, Fuller married Mabel Chappell. She also had views on the project: hot water and central heating now had to be provided to the servants’ rooms as well as the guest rooms. The tempo picked up as the Fullers were anxious to move into their home - but this was not achieved without friction. On July 1, 1912, Brakspear records a meeting with Fuller, ‘who informs me that he has got another man and another builder to do the church’. The new architect was C. H. Biddulph-Pinchard, who designed the church-organ case, painted by ‘Miss Maurice’. In 1943, the Fullers gave Great Chalfield to the National Trust. Their grandson and his wife, Robert and Patsy Floyd, still live there, gardening energetically and opening their doors to the many film crews who use it as a location. Few houses are shown to the public with greater scholarship.

One achievement that deserves comment relates to a photograph published in the 1914 Country Life articles: nearly all the furniture shown in that image, some of which had been dispersed, has been returned to the place it then occupied. Great Chalfield changes while remaining magically the same.

Great Chalfield Manor: The magic of the Middle Ages

The serene beauty of this magnificent 15th-century manor house belies a complex and eventful history.

Chisenbury Priory: A handsome and quirky streamside garden developed over decades

Tim Longville discovers how successive owners and artists have made their mark on the grounds of an ancient streamside property.

Alexander 'Greek' Thomson: Glasgow's visionary architect

As we celebrate the bicentenary of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Gavin Stamp considers the remarkable way in which he adapted principles