Fulbeck House: A wonderful home 'that arrests the eye as an ideal of English country living'

Fulbeck House, Lincolnshire — the home of Claire Van Cleave — is a little-known house of about 1700 that has been the subject of tactful restoration for a period of more than 20 years. Jeremy Musson looks at its fascinating history. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

The vicissitudes of the agricultural and political economy in Lincolnshire during the 20th century meant that it suffered the greatest number of losses of country houses anywhere in Britain. To encounter a well-restored and well-loved building such as Fulbeck House, therefore, a fine example of a compact residence built for a prosperous owner in about 1700, on the edge of Fulbeck village, is particularly uplifting and edifying.

This is limestone country and the more substantial stone houses of this period often seem closely related, as if common products of a strong local building tradition. The more ambitious also appear to be aware of the great 1680s aristocratic seat of nearby Belton House and its 10-bay east façade, in particular.

Such is the case with the entrance front of Fulbeck House, which is constructed in coursed, locally quarried limestone with ashlar quoins (Fig 1). It stands two storeys high and possesses a hipped roof — now slate, but originally stone tile — inset with a pair of pedimented dormer windows. There is a deep eaves course on this front only and the architectural detailing is crisply carved; the tall windows with lugged architraves, a deep string course dividing the elevation and the central front door with an unusual segmental pediment ornamented with exaggerated modillions of an oddly Baroque character.

To the south side of the door, two ground-floor windows retain early-18th-century (perhaps original) thick-profiled sash windows with smaller panes, 12 over 12, whereas the others are later-18th-century six over six and, to the north, later 19th century, with two panes only.

Fulbeck House had grown over the centuries, but the composed dignity of this front has clearly never lost its appeal. As a result, it has preserved its role throughout as the show front of the building. It has also determined the stylistic character of the most important additions to the house in the 1850s or 1860s, when an additional reception room and bedroom were added to the north. Other minor alterations are less self-conscious; there is an 18th-century extension of 2½ storeys to the south and some further modest practical additions of about 1900 to the west, in brick.

Part of the appeal of Fulbeck House lies in the simplicity of its original square layout around a well-worn, stone-flagged hall, now a sitting room, between two smaller rooms, one forming the handsome dining room and the other a former parlour. A staircase hall also opens off one side of the room (Fig 5). The staircase, with its paired turned balusters and stout moulded handrail, rises to a landing and returns to the main landing; the principal bedrooms face east over the entrance.

The date and patronage of the present house are as yet unknown and the building probably replaces an older house on the site. As a village, Fulbeck is unusual for the number of houses it possesses that are associated with small landed estates, many of which remained with the same families well into the 20th century. The main gentry house, however, is Fulbeck Hall, which was largely rebuilt in the 1730s and remained for a long time a home of the Fane family. A branch of this family still lives at another local building, the 16th-century Fulbeck Manor, where many of the Fane family portraits are today.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fulbeck House apparently attaches to no manorial title, but is undoubtedly one of similar architectural character and status to several admired rural houses in the region, such as the Manor House, Harringworth, of 1695, which retains its mullioned and transomed windows, and local townhouses. No single architect or master-builder can be identified for the house, but the designer is likely to be associated with one of the quarries at Ancaster or Leadenham, which lie close by. Alternatively, it’s not impossible, given its relative scale, that its builder came from one of the more distant centres of stone building in this district, most probably Stamford.

In an interesting reflection on the changing social status of the medical profession — with echoes of the novels of Trollope and Gaskell — it appears that, for much of the early and mid 19th century, Fulbeck House was the home of surgeons and their families. In the 1790s, it was owned by a William Fawcett and leased by his son-in-law, John Darley, who then let it to one Thomas Sharp, a surgeon and apothecary.

Sharp was presumably a family connection, as his wife was born Elizabeth Fawcett. In 1819, Sharp bought the freehold and, when he died in 1825, he was celebrated as having been a surgeon in Fulbeck for 44 years. Fulbeck House then passed to his daughter’s husband, Charles Smith, also a surgeon, whose large family is listed as resident in the 1841 census, with a young assistant surgeon also in residence. They are both memorialised in the parish church.

By 1851, the house had become the home of Mary Noel, widow of Col Christopher Noel of Wellingore and Walcott. She appears to have considerably extended the building at a cost of £800, which presumably included the substantial two-storey addition to the north-west (Fig 7). This addition can be roughly dated by a 19th-century photograph in the Fane albums in the Lincolnshire Record Office, which shows the building before its extension, but is labelled ‘Mrs Noel’s house’. The low brick wing to the south is a curious addition and might have been related to the surgeons’ practices. Mrs Noel died in 1873, and the house became the residence of another widow, Frances Houson, who shared the house with her son, Capt Henry Houson, in whose family the property remained until 1938.

The house was divided into flats after the war and returned to a single dwelling by Mr and Mrs Cook in the early 1990s. In 1997, Fulbeck House was bought by Claire Van Cleave, who had studied at the Courtauld and Christ Church, Oxford, a published expert on Italian drawings, and her late husband, Kent Brainerd, a music producer and property developer, with whom she shared a keen interest in historic buildings and paintings. Together, they contiuned the restoration and gradually and sensitively revived the integrity of the main rooms, re-opening fireplaces, restoring doors and windows, respecting surviving historic fabric wherever possible.

Their works have included re-creating wainscoting for the main entrance hall (made up by a local joiner) and adding the stone bolection-moulded chimneypiece to the same room (Fig 3). The drawing room was extended to the north, probably in the 1860s, and is now known as the Music Room. It has also been recently hung with a handsome warm-coloured yellow silk damask, specially woven by the Gainsborough Silk Weaving Company in Suffolk. The latter scheme was partly inspired by a room at Fairfax House in York, one of many houses the Brainerds explored looking for ideas and inspiration.

They also fitted out a comfortable, characterful new family kitchen in the historic kitchen, which retains the access to the hall on one side, the staircase hall on the other — taking full advantage of a former service room being the pivot of the house’s operation. A former servants’ hall has become a ‘butler’s pantry’ or store. Also leading off the main kitchen is a new study/library to the south side — fitted out with shelves to the pair’s own design, in a late-Regency character — in the place of a former pantry, with Watts & Co ‘Sanitary’ Paper (Fig 4). The bookshelves are filled with reference works on English architecture and Italian art in equal measure.

The interiors of this house have a comfortable, well-judged character. Carefully chosen colours — for instance, a regionally patriotic Lincoln Green in the dining room (Fig 2) — give the house a mellow flavour, with different accents chosen partly depending on the directional daylight. There is also a happy mixture of inherited, mostly British antiques, many of which came from Dr Van Cleave’s family in Chicago, who were keen collectors. The rooms are further enlivened by a collection of striking portraits, principally of women sitters, collected over the past 25 years and which hang alongside family portraits.

There are moments, too, of inventive insertions, including the imagined view of an extensive formal garden radiating out from the house and pavilions inspired by those at Athelhampton, in Dorset, with a portrait of the couple walking in the garden (Fig 6). This was painted by Mao Wen Biao — the Chinese-born artist of the famous murals at The Ritz and the RAC in London. This part-real and part-invented view sits in the internal window above the main staircase landing; this was originally an external window that became internal when additions were made in the late 19th or early 20th century. The attractive and distinctively large-scale Rococo plasterwork friezes in the dining room appear to have been installed in the late 20th century, but work well, together with the mid-18th-century-style chimneypiece in this room.

A large garden is framed with mature trees and was completely cleared and renewed by Dr Van Cleave and her husband. They laid out new walks and yew hedges, creating an appropriately formal setting for the house. The south side of the house has a good range of stables and coach house and other outbuildings in brick with limestone dressings, tactfully converted to cottage residences, around the spacious courtyard.

Remarkably, with their architectural enthusiasms and energy, and the entrepreneurial interests of Brainerd, the couple carried out this work in parallel with the rescue and restoration of nearby Stubton Hall, a major country house by Jeffry Wyavtille, which had been a school, and was in poor condition when they bought it in 2006). They restored and opened it as a wedding venue, which has been run with considerable success by Dr Van Cleave. She has been generous in her advice to others in the challenges of the historic country-house hospitality business and maintains a career as an art historian, too, currently cataloguing drawings from the Farnese collection at the Museum of Capodimonte in Naples, Italy.

Fulbeck House is one of those more compact homes that arrests the eye as an ideal of English country living. It is good to find such a one in the hands of someone who cherishes and cares for it with such devotion.

Stubton Hall's magnificent transformation 'from a gloomy shell into a dream country house'

Stubton Hall in Lincolnshire is a distinguished Regency country house which makes its first appearance in Country Life following a

The Travellers Club: Home to London's globe trotters for the past 200 years

To mark the bicentenary of The Travellers Club, the oldest club in Pall Mall, John Martin Robinson tells the story

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

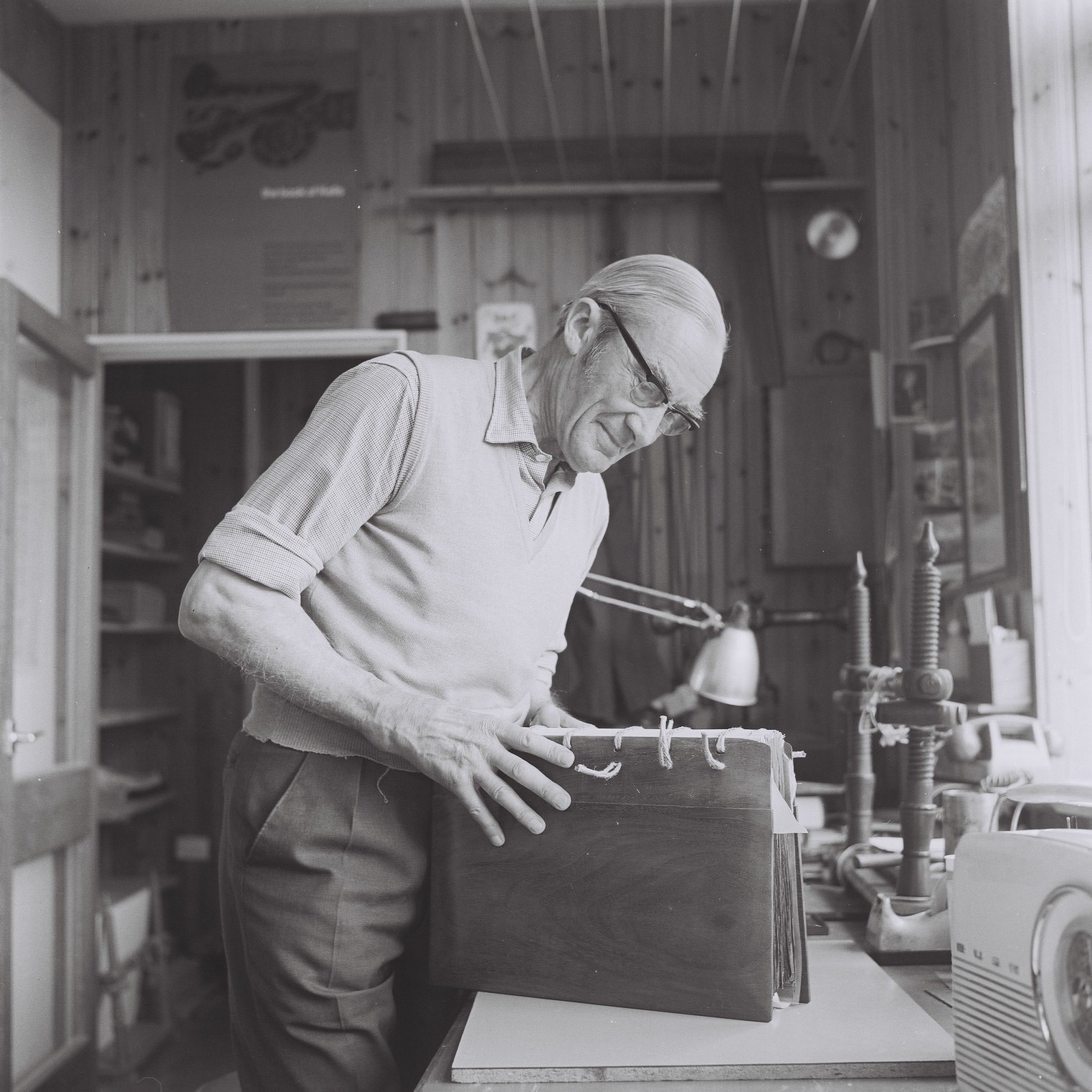

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani